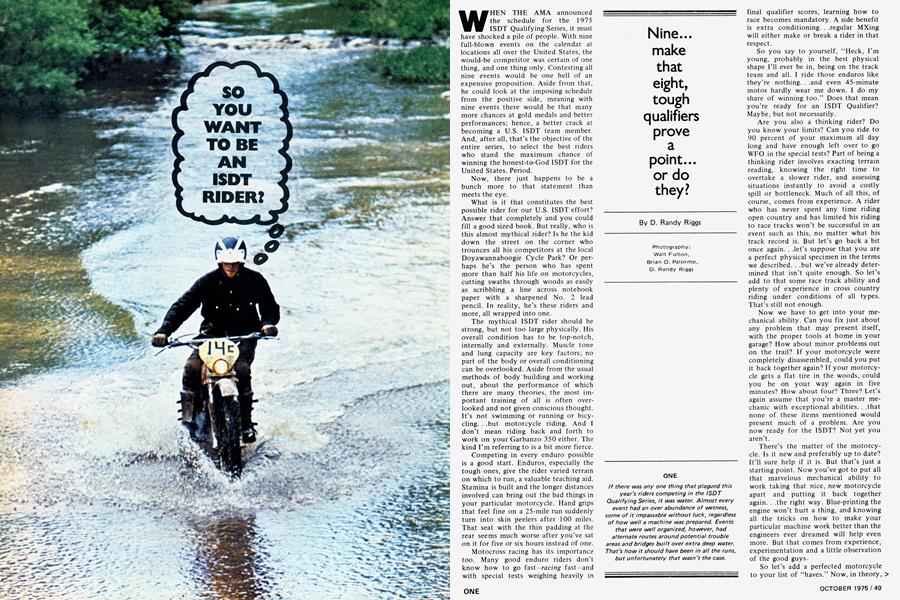

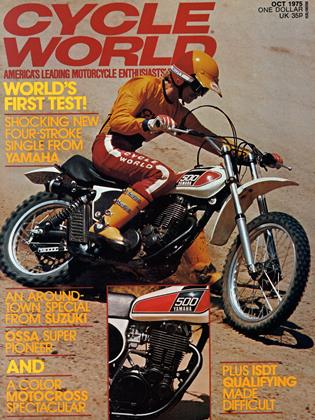

SO YOU WANT TO BE AN ISDT RIDER?

Nine... make that eight, tough qualifiers prove a point... or do they?

D. Randy Riggs

WHEN THE AMA announced the schedule for the 1975 ISDT Qualifying Series, it must have shocked a pile of people. With nine full-blown events on the calendar at locations all over the United States, the would-be competitor was certain of one thing, and one thing only. Contesting all nine events would be one hell of an expensive proposition. Aside from that, he could look at the imposing schedule from the positive side, meaning with nine events there would be that many more chances at gold medals and better performances; hence, a better crack at becoming a U.S. ISDT team member. And, after all, that's the objective of the entire series, to select the best riders who stand the maximum chance of winning the honest-to-God ISDT for the United States. Period.

Now, there just happens to be a bunch more to that statement than meets the eye.

What is it that constitutes the best possible rider for our U.S. ISDT effort? Answer that completely and you could fill a good sized book. But really, who is this almost mythical rider? Is he the kid down the street on the corner who trounces all his competitors at the local Doyawannaboogie Cycle Park? Or per haps he's the person who has spent more than half his life on motorcycles, cutting swaths through woods as easily as scribbling a line across notebook paper with a sharpened No. 2 lead pencil. In reality, he's these riders and more, all wrapped into one.

The mythical ISDT rider should be strong, but not too large physically. His overall condition has to be top-notch, internally and externally. Muscle tone and lung capacity are key factors; no part of the body or overall conditioning can be overlooked. Aside from the usual methods of body -building and working out, about the performance of which there are many theories, the most im portant training of all is often over looked and not given conscious thought. It's not swimming or running or bicy cling. . .but motorcycle riding. And I don't mean riding back and forth to work on your Garbanzo 350 either. The kind I'm referring to is a bit more fierce.

Competing in every enduro possible is a good start. Enduros, especially the tough ones, give the rider varied terrain on which to run, a valuable teaching aid. Stamina is built and the longer distances involved can bring out the bad things in your particular motorcycle. Hand grips that feel fine on a 25-mile run suddenly turn into skin peelers after 100 miles. That seat with the thin padding at the rear seems much worse after you've sat on it for five or six hours instead of one.

Motocross racing has its importance too. Many good enduro riders don't know how to go fast-racing fast-and with special tests weighing heavily in final qualifier scores, learning how to race becomes mandatory. A side benefit is extra conditioning. . .regular MXing will either make or break a rider in that respect.

So you say to yourself, "Heck, I'm young, probably in the best physical shape I'll ever be in, being on the track team and all. I ride those enduros like they're nothing. - .and even 45-minute motos hardly wear me down. I do my share of winning too." Does that mean you're ready for an ISDT Qualifier? Maybe, but not necessarily.

Are you also a thinking rider? Do you know your limits? Can you ride to 90 percent of your maximum all day long and have enough left over to go WFO in the special tests? Part of being a thinking rider involves exacting terrain reading, knowing the right time to overtake a slower rider, and assessing situations instantly to avoid a costly spill or bottleneck. Much of all this, of course, comes from experience. A rider who has never spent any time riding open country and has limited his riding to race tracks won't be successful in an event such as this, no matter what his track record is. But let's go back a bit once again. . .let's suppose that you are a perfect physical specimen in the terms we described. . .but we've already deter mined that isn't quite enough. So let's add to that some race track ability and plenty of experience in cross country riding under conditions of all types. That's still not enough.

Now we have to get into your me chanical ability. Can you fix just about any problem that may present itself, with the proper tools at home in your garage? How about minor problems out on the trail? If your motorcycle were completely disassembled, could you put it back together again? If your motorcy cle gets a flat tire in the woods, could you be on your way again in five minutes? How about four? Three? Let's again assume that you're a master me chanic with exceptional abilities. . that none of these items mentioned would present much of a problem. Are you now ready for the ISDT? Not yet you aren't.

There's the matter of the motorcy cle. Is it new and preferably up to date? It'll sure help if it is~ But that's just a starting point. Now you've got to put all that marvelous mechanical ability to work taking that nice, new motorcycle apart and putting it back together again. . .the right way. Blue-printing the engine won't hurt a thing, and knowing all the tricks on how to make your particular machine work better than the engineers ever dreamed will help even more. But that comes from experience, experimentation and a little observation of the good guys.

So let's add a perfected motorcycle to your list of "haves." Now, in theory, you have most of the main essentials to make a good ISDT rider, or better yet, let’s take it for granted that you are exceptional in all the categories we mentioned. None of the broad headings should offer you any particular problem. Now all you have to do to earn a spot on the team is prove to the right people in the AMA that you are capable of competing in the ISDT.

This is done, of course, through individual performance in the AMAsanctioned qualifiers. They’re supposedly set up to provide a system whereby Joe Exceptional of Anywhere, U.S.A. can earn a spot on the team based on his capabilities and riding ability. . .sort of. But let’s keep in mind above everything else that the prime goal of this all is to field the best possible team with the best possible chance of winning the ISDT. In effect, that means that rider selection is based on more than just individual performance in the qualifiers. Weighing far more heavily in team selection is previous Six Day experience and “available support;” and one or the other, or both, is bound to eliminate many a decent rider from the list. In a way this is truly unfortunate, but realistically the only way at present to come up with the strongest possible team for the biggie.

Consider this year’s series, for example. To contest each and every one of the original nine events (Mississippi’s infamous Devil’s Swamp Qualifier was canceled due to severe weather conditions), would be a giant undertaking for the average rider. Expenses alone, not including the cost of a new machine, could run in the neighborhood of 3 to $4000 dollars. Add to that figure lost wages if time had to be taken off from work, and perhaps even a lost job if the series was given total priority.

Of course, running each of the eight events was not a requirement. The AMA was only going to score a rider’s performances at his four best events. In this case it was decidedly in your favor to earn four gold medals if possible, to stack the deck a little in your favor.

And now we’re down to the nittygritty. You’ve done everything right and you’ve scored well in special tests and come up with a bunch of golds and strong finishes, proving to everyone that you are capable in the areas we mentioned earlier. Does that mean you and your machine will be packed up on an airplane in October and shuttled off to the Isle of Man? Chances are that it doesn’t.

We know you got your letter of intent in nice and early, and you did a real fine job in the series. . .but. . .uh, you’ve never ridden the Six Days before and you don’t ride for a factory, so we’ve gotta figure out a way to keep you going in the Six Days. . .1 mean, you don’t have any support and haven’t learned the finer points of cheating, and you don’t have much in the way of spares and things. So we’re gonna have to bump you down some on the list. Sure, we know some of these factory guys had a bad year in the qualifiers and only wound up with a couple of silvers and some bronzes. . .but they’ve run in the ISDT before, ya know, and their company is gonna pay their way and stuff. . .makes it a whole lot easier on us. But don’t worry, you’re on the list, see. Only right now we’re not sure how many riders they’re gonna let us use this year. If they let us have 40 riders, you’re in, but we don’t know right now. But just in case, ya better send in your deposit of a couple hundred dollars to make sure you have a reservation on the plane. . .in case you can go. Oh, by the way, the deposit isn’t refundable, so you kinda have to take your chances.

How would all this have set with you had you been the one running in the eight-event grind? Especially if you stop to consider the hassles and stumbling blocks that were present at the majority of events. Only California City, Calif., Ft. Hood, Texas and Pell City, Ala., were run without serious difficulties. Of the three, the Texas and Alabama events were the best in terms of being true tests of an ISDT rider. California needed a tighter schedule and more varied terrain. The other events in New Jersey, Oregon, Missouri and New York were poorly organized, with little or no alternate plans for bad weather conditions.

Water is one thing, but when ma chines get washed out from under riders during stream crossings, that's a bit much. Next year, there should be fewer events deemed ridable regardless of weather conditions; they shouldn't con flict with the dates of a National En duro, and there should be more special tests. And organizers should stick closer to the rules, making cheating more of a challenge. At most of the events, cheat ing was done blatantly and out in the open. More careful were riders who switched engines and machines. though it was fairly easy for them, as well.

The two top events showed a remark able contrast in organization. Ft. Hood, Texas, was run with the help of scores of Army personnel, while the Alabama event was put together by a haPdful of local people. The important thing was, however, that each was a pretty good example of how ISDT Qualifiers should be run. Let's just hope that next year they'll all be that way. Let's also hope that deserving private riders have a better crack at making the team. And would it be too much to ask that our very best riders comprise the World Trophy Team? Three members of the 1975 World Team could stand replace ment by our Club Team, but that's a whole other story. . .isn't it?

1975 U.S. ISDT TEAMS

WORLD TROPHY TEAM

SILVER VASE TEAM

MANUFACTURER TEAMS Can-Am

Ossa Cutler, Lavoie, Vincent Penton "A" Cranke, Jack and Tom Penton Penton "B" Jensen, Leimbach, Young Penton "C"

Rokon

CLUB TEAM

ADDITIONAL RIDERS

(To be considered in the event of openings)

Mark Adent, David Ashley, Charlie Bethards, Ben Bower, Chris Carter, Jim Fogle, Jeff Gerber, Jerry Harris, Barry Higgins, Dave Hulse, Ron LaMastus, Kenny Maahs, Dave Mungenast, Jim Piasecki, Stan Rubottom, Drew Smith, Don Stover, Doug Wilford.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

October 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Cycle World Interview

Cycle World InterviewEd Youngblood & Gene Wirwahn

October 1975 By Ben Hands -

Special Competition Feature

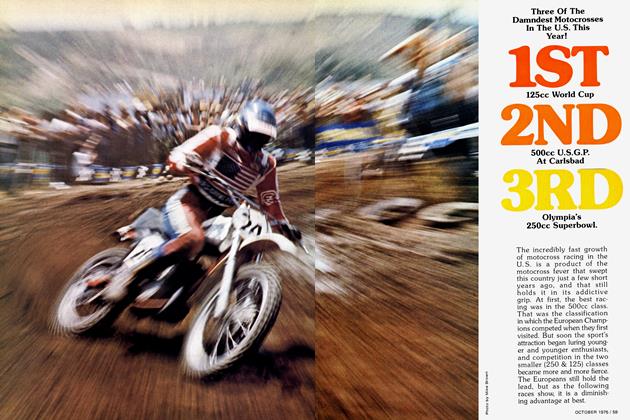

Special Competition FeatureThree of the Damndest Motocrosses In the U.S. This Year!

October 1975 -

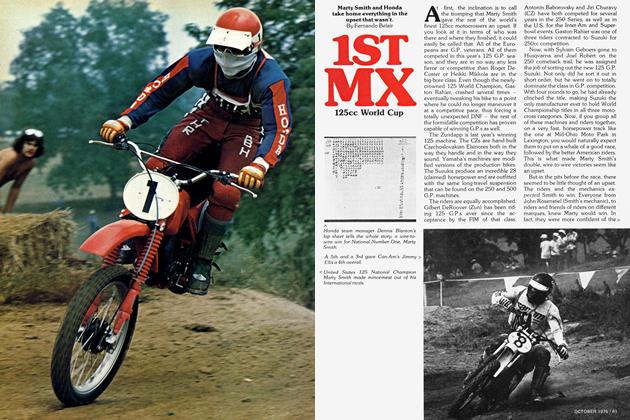

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition Feature1st Mx 125cc World Cup

October 1975 By Fernando Belair