Ed Youngblood & Gene Wirwahn

CYCLE WORLD INTERVIEW

Inside the American Motorcycle Association

Ben Hands

JUST WHAT IS the American Motorcycle Association? And who is it? It has been called (see CW, Feb., 1972) a flawed, unrepresentative dictatorship-worse than dead weight. Industry pawns, fence straddlers, men afraid of everything are said to be at the helm. What does the AMA think of such charges and what does the AMA, under relatively new leadership, do for motorcycling? I had decided to find out.

For the non-competitor, the men in the key positions at the AMA are Ed Youngblood, the general manager and Gene Wirwahn, the legislative director. A meeting was arranged at the AMA ’s new office building in Westerville, Ohio, on the outskirts of Columbus.

Youngblood, Wirwahn and I meet in a very large corner office. It is paneled and the furniture is covered with a huge, garish houndstooth check, a reminder of Russ March, Youngblood’s predecessor, who left the position and the office in a storm of controversy. Incongruously, a copy of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying is among the reams of business on Youngblood’s desk.

Youngblood is a short, stocky fellow who grew up in Oklahoma and was pursuing a doctorate in 16th-century English literature when the unwelcome prospect of teaching and a newly kindled interest in motorcycles persuaded him to take the editorship of Cycle News. From there he moved to the AMA NEWS and he came up through the ranks to his present position at the head of the organization in three years.

Youngblood is about 30 years old and he is married with two young sons, who will have to decide for themselves, he says, whether they want to become motorcyclists. Youngblood himself rarely rides, but not from lack of desire. Although he has located and bought back his first motorcycle, a BMW R27 from graduate school days, the demands of his job have prevented him from restoring it to running condition yet. A thoughtful man of broad interests, Youngblood is not afraid to speak to the organization 's faults and mistakes as well as its positive attributes.

Wirwahn, on the other hand, emphasizes the positive and he speaks in very enthusiastic terms of the AMA’s accomplishments and its hopes for the future. A nervous man, in constant motion, Wirwahn studied philosophy and Sanskrit in college. He came to the AMA from a successful law practice in Birmingham, Alabama, where he had tired of hearing from his partners about weekend “life on the houseboat’’ and getting, in response to his tales about enduro activities, the uninterested reply that he “ought not to be doing that anyway because it’s unsafe.’’ Wirwahn rose to a brief road racing career from modest beginnings on a Vespa Cruisaire that was “very, very economical.’’ Now he owns trials and street motorcycles and lives with his wife near Westerville. He has no children, but he does have an English bulldog, which he also plans to let make up its own mind about becoming a motorcyclist.

QUESTION: Ed, I have always thought of the AMA as a large, mysterious organization. Is there any easy way to understand how it is organized, its different functions, the chain of command and so forth?

YOUNGBLOOD: I don’t think there is. I’ve often felt that the AMA’s biggest problem for the staff or even for its trustees is that it is one of the most complicated organizations in this country. Basically, it is a race-sanctioning body, a governing body, and a member service organization. I know of only one other organization that both sanctions competition and provides member service, and that’s the National Rifle Association. Even they are different from us because they are best known for their member service activity, their lobbying. A lot of the public does not even realize NRA sanctions shooting competition in the U.S., whereas AMA is best known for racing sanctions and officiating, and I think a lot of motorcyclists don’t even realize that it is also a member service organization. There is nothing like AMA in any other motor sport organization.

WIRWAHN: An interesting aside to this is that motorcycling is so multi-faceted. Riding a trials bike and riding a longdistance touring bike are both motorcycling, but they are different ends of a spectrum. Since the AMA involves itself with every one of these facets, I think this complexity is really inherent. If you’re going to be the AMA, you’re going to be involved in all these things, and you end up being complex.

QUESTION: How big is the AMA? Start with the staff.

YOUNGBLOOD: There’s a staff in

Westerville of about 45.

QUESTION: How about fiscally?

YOUNGBLOOD: The AMA had a

budget close to $4 million when the annual dues were $12. At the present time dues are lower and the budget is close to $3 million. The major part of that income is from membership and then there are other sources like sanction fees, fees for radio and TV rights and so on that provide substantial amounts.

QUESTION: Are all those sources other than membership dues connected with competition?

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes.

QUESTION: What proportion of AMA income comes from membership?

YOUNGBLOOD: This is just a wild guess but I would say about 50 percent.

QUESTION: What is the new policy on membership?

YOUNGBLOOD: It’s a program we developed in response to membership opinion. There are three types of membership: competitor, enthusiast and associate. It used to be that there was a single $12 membership whether you raced or rode a street bike. Now to enter any AMA-sanctioned amateur or semiprofessional event, you need a competitor’s membership for $10 a year. For the road rider and non-competitor, we have the enthusiast membership for $8; and the associate membership for spouses and dependents is $6.

QUESTION: What immediate, tangible benefits does an enthusiast get for his $8?

YOUNGBLOOD: The enthusiast gets a membership card that qualifies him to enter any sanctioned road event, just as the competitor can enter any amateur or semi-pro racing event. In addition, all three classes of membership receive death or dismemberment insurance coverage of up to $2000. Quite often insurance companies consider motorcycling a hazardous activity and won’t pay off if someone is injured or killed riding or competing, but AMA will pay your family if you are killed riding on the street.

WIRWAHN: Or in an event.

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes, although we

would not cover our members in an unsanctioned event because we wouldn’t know whether it meets our safety standards, whether there was an ambulance on hand, and so on. The members also receive a monthly newsletter which reports on general association activities, avoiding racing coverage.

WIRWAHN: Another tangible benefit is a membership pin showing how many years the owner has belonged to the AMA. Once he reaches 25 years he gets a life membership, all paid up. Each renewal gets a reflective AMA logo decal. It always makes me feel good to see one on the back of a car or truck.

QUESTION: There’s a magazine too, isn’t there?

WIRWAHN: That’s a separate subscription for $5 per year.

QUESTION: My impression is that a very small proportion of the motorcycle owners in the U.S. are actually members of AMA.

WIRWAHN: It’s under 4 percent without question. There are four million registered bikes in the U.S. and 140,000 members in the AMA. But I think it can be said truthfully that the 140,000 AMA members are the most active motorcycle owners with regard not only to competition, but also to legislation, interest in the sport and everything else.

QUESTION: Informal motorcycling is rather individualistic. Unless you are one of the few who belong to a club, you ride by yourself or with only one or two people. Do you think that this solitary nature contributes to the fact that more riders do not join AMA?

YOUNGBLOOD: Motorcycling is primarily a social activity, and the loner image is bull in spite of everything that is done to promote it. Motorcyclists like nothing better than getting together with other motorcyclists. A trail rider would rather go with other guys even if it means he has to hold back and wait for them or kill himself to keep up. I’ve never seen an atmosphere of stronger camaraderie than at a major road tour.

QUESTION: Well then, why don’t more motorcyclists belong to AMA?

WIRWAHN: One reason they do belong to AMA is to ride in sanctioned events, but if you ride your motorcycle in the woods or in a National Forest or back and forth to work, you technically don’t have to belong to AMA. However, a large number of people are enjoying these things because of work AMA is doing. We need to awaken some awareness in the fellow who rides back and forth to work or who rides with his family on weekends that if it were not for the AMA he couldn’t be doing it, and that if he doesn’t get behind the AMA, he won’t be doing it to the degree he likes in the future. Our present membership are those persons who are really concerned that their hobby or their way of transportation continues to exist in the future. The rest ride because it’s fun, because it takes their minds off whatever is unpleasant in their lives.

QUESTION: Who are the members of the AMA?

WIRWAHN: They are a pretty diverse group. One of our surveys showed that a good percentage were college educated, a large percentage had finished high school, and about the same percentage had gone to graduate or professional school as had not finished high school— about 14 percent I think. The average family income was about $15,000, and a majority were buying a home and owned one or more motorcycles.

QUESTION: Does the enthusiast member participate in running the AMA?

YOUNGBLOOD: There are three general members of the board of trustees, one from each AMA region, and they are elected annually by the competition and enthusiast members from their region.

QUESTION: How big is the board of trustees?

YOUNGBLOOD: Thirteen members.

QUESTION: Three out of 13 isn’t many.

YOUNGBLOOD: At this level, the board of trustees, the three elected members cannot have any promotional contact with the industry, not even at the dealer level. But of the other 10, two are from the press and eight from the industry. So I guess you would have to say that AMA is basically industry managed.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 55

QUESTION: Do the three elected members have any influence?

YOUNGBLOOD: In the two years I have worked with the board, they definitely have had a strong influence and have brought a point of view that was lacking before. Someone may say there is a lack of opportunity for participation by members, but I don’t know how we can have it with 140,000 members. The AMA has recognized the problem and has moved toward a solution by putting the three average members on the board of trustees. I don’t know how I personally feel about the problem. On the one hand a perfect democracy or, on the other, a beneficent dictatorship, just aren’t going to exist.

WIRWAHN: The Canadian Motorcycle Association is a democracy, and although it’s much smaller than AMA, it’s in constant turmoil. They can’t get anybody in long enough to do any good. Even those members of our board who are employed by industry are working for a user group when they put their director hats on. I can think of several examples where I have seen these representatives vote for things that weren’t very beneficial from the industry viewpoint, but were good for the rider. That’s true of our staff here too. They know how the industry benefits us and how we can benefit them, but if you go out there and ask them who they work for, they will say the riders without thinking about it.

QUESTION: How do you feel about the existence of other groups like the New England Trail Riders Association or MORE (Motorcycle Owners Riders and Enthusiasts) in California?

WIRWAHN: As far as I’m concerned, the more the better. Whatever is good for motorcycling is good for the AMA.

YOUNGBLOOD: The leaders of those groups should feel free to come to us and discuss problems and policies. No one should be jealous or worry about who is going to get the credit, but I do think that the worst thing we can do is go into a public hearing with these groups and present different points of view. We have to make a united public front, however we accomplish it.

QUESTION: In other words, you would like these groups to have an official association with AMA, but you are still willing to work with them without that.

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes.

QUESTION: Ed, what are your responsibilities in the AMA? Are you responsible for everything, or do you deal mainly with specific areas?

YOUNGBLOOD: My title, general manager, pretty well describes it. When I got that title it was cause for much humor in the coffee room, because it sounded like top man in a supermarket, but that is pretty accurate.

QUESTION: Because of the position’s diversity?

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes, it’s very diverse and general, except that, as the position is defined by the trustees, I am expected to make a special effort to avoid becoming involved in competition. We have a separate director of competition, and as general manager, I concentrate on the areas of member service, legislation, public relations, and that type of thing.

QUESTION: Then competition is an autonomous part of the AMA?

YOUNGBLOOD: Well, in the past, the executive director’s position was weakened by competition. He always ended up running competition whether he liked it or not, and membership service suffered. Now a director of competition has been appointed and that frees me to do other things.

QUESTION: How about your job,

Gene?

WIRWAHN: The title legislative director is both descriptive and deceiving. At the simplest level I direct the legislative department, which is a watchdog on legislation relevant to motorcycling. We try to influence legislation to make certain that it is beneficial to motorcycling. It could be no-fault insurance, a land-use bill or whatever. My department also gets anything that has to do with city ordinances, county ordinances, state statutes, anything of a quasi-legal nature.

QUESTION: Gene, does your department handle any litigation for the AMA?

WIRWAHN: The AMA as a sanctioning body is often sued, for example, when a spectator is injured, but we have an outsicje legal counsel for that and our insurance carrier has lawyers. My department’s role is solely to gather information and not to participate in a defense. We also retain counsel and become involved in cases of special interest to the AMA and to motorcycling. For example, there was litigation concerning the 48th International Six Days Trial (ISDT) and, more recently, the Barstow to Vegas race. We’re also in the process of intervening on behalf of the Hoosier National Forest in a lawsuit brought by the Isaac Walton League of Indiana. Years back we defeated the Michigan helmet law through litigation and we successfully brought suit to allow motorcycles on the Atlantic City Expressway in New Jersey. We are still working on legislation to open the Garden State Parkway to motorcycles.

QUESTION: Do you have any staff?

WIRWAHN: I have a legislative analyst on my staff and we are adding a legislative coordinator whose job will be to go into the field to get local motorcyclists to be politically active—not just in supporting candidates and lobbyingbut also in attending hearings and speaking on behalf of the organization. There is a great potential for getting people involved at the grass roots level and keeping them involved.

QUESTION: What’s the AMA’s history in political activity?

WIRWAHN: It goes way back. Before I came on board there was a Political Frontiers Program, which was a dynamite idea, except that it was ahead of its time and it had no follow-up. You can stir people up easily enough, but you’re not going to do any good unless you keep them involved. Our new man will do that, but on a low-key basis.

YOUNGBLOOD: I think the really important difference in the work of this new man will be that he is going to help local clubs become self-sufficient as local political and civic groups. Before, we tried to tie in motorcyclists with the established political system. We tried to teach motorcyclists how to get in touch with local parties and work with them. Now we’re going to concentrate on making motorcyclists politically selfsufficient.

QUESTION: It would seem to me that you would be making quite a stride politically if you got candidates for election and government officials to recognize motorcycling and to feel that they had to be informed and ready to take positions on questions pertinent to motorcycles. At this stage they tend to ignore them.

WIRWAHN: It’s human nature—the squeaky wheel gets the grease. Any public official, elected or appointed, is going to pay attention to the people who talk to him. I have never met a public official who looked me right in the eye and said, “I don’t like motorcycles.” It’s never happened. I have met a large number who have never thought about it. That’s the job of motorcyclists: to see that officials do think about us. A good example of what can happen is rain grooving. When they started grooving highways, it never entered anyone’s mind that it might have an adverse effect on motorcycles.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 86

YOUNGBLOOD: Right. I visited the Department of the Interior on behalf of the AMA about three years ago and while I was waiting to see an undersecretary in the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) I looked over a display of their literature. There were tons and tons of publications on every form of outdoor recreation except motorcycling. Nothing said motorcycles were good or bad, nothing said they were destructive or non-destructive, nothing! It was then that I realized that the problem was not hostility. It was ignorance. Ever since then we have been trying to educate government officials. We receive letters from the Secretaries of the Department of the Interior and the Federal Energy Office that indicate we are making progress, but it’s a long process.

WIRWAHN: The AMA is recognized by almost every agency as being the representative of 140,000 motorcyclists and an authority on motorcycling. We are the only responsible nationwide group agencies can contact for information. We have had literally thousands of requests for the Trail Rider’s Guide to the Environment, and we’ve been very active in fighting no-fault insurance for motorcycles.

QUESTION: How do you know what your members want?

YOUNGBLOOD: We get back an awful lot of letters commenting on items in the newsletter and then periodically we use the newsletter to publish questionnaires. We have been doing that three or four times a year and it makes decisions a hell of a lot easier when they are based on some sort of collective opinion.

Our Amateur Competition Congress is elected by clubs in each district and it sets rules for competition. The Congress has also started having committees on public relations and legislation. They pass resolutions based on the opinions of their constituents and these are useful to the legislative director.

WIRWAHN: In a recent newsletter survey we asked the members what they viewed as the proper function of the AMA. Should it be a discount merchandise deal, a political interest group or a public relations force..Ten percent went for the merchandise concept, 12 percent for a political interest group and more than 55 percent said it should be a national public relations force. We are going to be doing more of this in the coming year. I feel my job is a trust and that I have a duty to work for the 140,000 people who are my bosses. For example, I recently asked in the newsletter how people felt about the 55-mph speed limit. To be honest, I’m opposed to it and I hoped that I’d receive a deluge of mail backing me up so I could begin to raise heck about it. Well, so far the results are about 60 percent against and 40 percent for. I have to ask myself whether I should spend time and money lobbying against something that 40 percent of the members think is pretty neat. We are going to be doing more of this. For instance, we are going to be surveying the membership about “lightson” legislation.

QUESTION: It appears to me that you have always been in the position of trying to prevent unfair laws from being passed or trying to throw out bad laws that are already on the books. Is there any chance that you will reach a point where you can work for laws you want?

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 88

WIRWAHN: There is no doubt that the first year and a half of my two and a half years here were spent fighting fires and trying to get the cattle back in the barn. If anything ever started out on a negative side, it was land use, but I think we have turned that to an unqualified positive situation.

QUESTION: How?

WIRWAHN: By supplying information, by giving our members responsible instructions on how to ride and behave, by working for quieter motorcycles, by co-sponsoring a land-use seminar at TVA’s Land Between the Lakes, that sort of thing.

One of my top priorities is to come up with a model off-road registration law. We want to go to a state and say here’s a bill that will register off-road bikes, that will provide proper use of the registration fees, that will put a decal in the right place instead of a license plate that will tear off an important part of the body in a collision, that will identify the so-and-so that rode through your rutabaga patch—you know, a number of details we can live with.

To answer your question, yes, we have had to work on the defensive in many cases, but that is turning around.

QUESTION: How did AMA first become involved with off-road riding and land-use?

WIRWAHN: To answer that you have to go back to the 1972 Presidential Executive 11644 order requiring federal regulations for motorcycles on public lands. The AMA’s response to that was basically, “Thank you Mr. President for recognizing off-road motorcycling as a legitimate form of recreation.” And, of course, we delivered that response to the White House along with 250,000 signatures backing it up.

YOUNGBLOOD: We caught hell from parts of the motorcycle community for doing that. A few influential individuals based their feelings on a cowboy ethic and said, “It’s public land and if we can’t have the forest, we’ll burn it down.” They didn’t really say that but that was the attitude.

WIRWAHN: These people interpreted the Executive Order as the beginning of the end, but we took the view that although trail bikes could damage the environment and could conflict with other forms of recreation, these problems could be minimized or avoided by correct management. This philosophy got a lot of criticism, especially from the right-wing outdoor recreation groups in California. But when the Bureau of Land Management finally issued its off-road vehicle regulations, 450 million acres of land was considered open unless posted closed, and the same thing was true for the Forest Service’s 180 million acres.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

QUESTION: What kinds of things have you done to investigate motorcycles’ effects on the environment?

WIRWAHN : We cooperated with the TVA and the Motorcycle Industry Council (MIC) to sponsor a study on the demography of trail riders. Who are they and what do they expect from riding areas? AMA and MIC sponsored a similar study by Southern Illionis University and AMA has cooperated with Auburn University on a study of the effects of all kinds of noise on wild turkeys.

QUESTION: Has AMA contributed financially to these studies?

WIRWAHN: Yes, on several of them. We’d like to spend more money on this sort of thing, but we don’t have it.

QUESTION: Whose responsibility is it to get this work done?

WIRWAHN: That’s an interesting question. We are really unique in feeling any responsibility at all. Similar research doesn’t exist for other kinds of recreation. Originally we wanted someone to do a nationwide environmental monitoring program for motorcycles, but when we realized that one person couldn’t do that in a century of work, we developed the Trail Rider’s Guide to the Environment, which tells the rider how, when, and where to ride his trail bike with a minimum of adverse effect.

QUESTION: What else do you do for the off-road rider?

WIRWAHN: We held a seminar at

TVA’s Land Between the Lakes for 50 of the highest-ranking federal land managers we could get to attend. Prior to that I think you could say that the Army Corps of Engineers was passively anti-trail bike. They didn’t think about them. Since then the Corps has shown great interest in providing motorcycle areas. We are planning another seminar in 1975 for state land managers.

Rob Rasor, my assistant, and I have achieved a nationwide recognition as experts on motorcycling and land use, because we have spent more time on it than anyone else. We are in constant demand for appearances at state, federal and even city and county levels.

QUESTION: Is your position on offroad motorcycling changing as you become more experienced?

WIRWAHN: Our philosophy is coming around to the point of saying, “If there is a conflict, let’s work it out.” We are no longer going to step out. Trail biking has a right to exist, and maybe that right is because it does exist. You have to take the world as you find it and trail biking is very popular. It’s not going away. If it’s not provided for, then illegal use will continue. For example land use managers accept hiking, horseback riding, and ski touring without question. The BOR’s proposed North Country Trail through eight states provides for hikers and horses. BOR admits that human and animal waste will accumulate. But despite the fact that their own data show that motorcycles are more popular than horses, they exclude bikes because motorcycles are “preemptive.” That’s the sort of thing we have to work out.

(Continued on page 96)

Continued from page 92

QUESTION: Well, I guess we’ve pretty well covered off-road riding.

WIRWAHN: Yes, but there’s one more point I’d like to make. No matter how successful AMA is in this area, the future depends on the average motorcyclist and if he doesn’t feel any responsibility, then trail biking is going to go away. On vacation recently I witnessed two men riding their “trail bikes” down my parents’ street to the woods. The machines were actually motocrossers, and they had no mufflers at all. Now if I’m irritated by that, I am sure other people are too.

YOUNGBLOOD: That sort of activity in this day and age is about as appropriate as gunfights in the street. It’s from a bygone era that we can no longer tolerate.

QUESTION: What kinds of services can someone càll up the AMA and ask for?

WIRWAHN: We are on call 24 hours a day to help motorcyclists who are having problems. For example, the Thanksgiving recreation of 15,000 people depended on the Barstow to Vegas race and when the club called on us for help with the complex environmental impact statement, we gave it, and those people were able to enjoy their hobby on Thanksgiving Day. But obviously we don’t have the money to go help every rider who gets a speeding ticket or a parking ticket.

QUESTION: Would you want to if you had the money?

WIRWAHN: No, probably not, we have to take care of the problems that affect the most people.

QUESTION: If that’s the case, don’t a lot of people who do not belong to AMA, benefit from your work?

YOUNGBLOOD: To a certain extent the organization may be too philanthropic; this may be a basic weakness, that you don’t have to be a member to benefit from it.

WIRWAHN: But in some cases you do. In Georgia they have a “lights-on” law except when you are entered in a competition event sanctioned by the AMA. It’s similar in Virginia.

QUESTION: You mean AMA is named in the law?

WIRWAHN: Yes. One National Forest has ruled that competition events can be permitted on its land if they are AMA sanctioned, and the State of Florida’s motorcycle parks do the same.

(Continued on page 100)

Continued from page 96

QUESTION: That’s got some interesting anti-trust ramifications.

WIRWAHN: It really doesn’t. It’s just recognition that the AMA events are well run and that we are nationally and locally recognized as the motorcycling body.

QUESTION: What is the AMA doing internationally?

WIRWAHN: I should start by saying that the AMA is the United States representative to the FIM, the Federation Internationale Motorcycliste, which, in my definition, is the “United Nations of Motorcycling.” AMA’s affiliation with the FIM began about 1968 and in 1970 we were accepted as the U.S. representative. FIM meets for an annual congress where it makes rules and passes resolutions in the areas of road riding, track racing, motocross and trials, safety and engineering, road racing and so on.

Many people do not understand the need for participation in the FIM. It has, for example, been very beneficial for me to see how the Europeans handle problems with noise. Many of the problems we have here in the U.S. have, in many cases, been solved in Europe, so it’s a clearing house for ideas.

Because of our recognition by FIM, we are the only group that can sanction an FIM international event in the U.S.

QUESTION: Does that mean that U.S. competitors can compete readily in an international event?

WIRWAHN: Whenever an American

competes in an international event he must have an FIM license, and, in order to get that, he must have an AMA license.

YOUNGBLOOD: Since our AMA national license requirements are very stringent, age is about the only other requirement AMA license holders must meet to qualify for an FIM license. They must be 18 or, for motocross, 16 years old.

QUESTION: Putting the ISDT together was a real coup wasn’t it?

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes.

QUESTION: I know it had its tribulations too.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 100

YOUNGBLOOD: It certainly did. We definitely weren't ready for it, but I doubt that any nation is ever ready for it.

QUESTION: The reporting I've heard suggests that as more and more coun tries have a try at hosting it, your performance looks better and better by comparison.

YOUNGBLOOD: As a matter of fact, some very gratifying changes resulted from that event. FIM is making the ISDT simpler, more comprehensible and less expensive. When we went back to the FIM meeting in Madrid after that ISDT, Otto Sensburg, the German dele gate who developed the scoring system, said that the Europeans had to go to America to get perspective in the ISDT. The U.S. held up a mirror that showed FIM its own faults. He said the troubles experienced resulted from the design of the event, not the failures of the organizer. For instance, the scoring was too complicated for anyone to under stand. Even if scores could be produced by 10 o'clock at night, they were worthless to the media because they were so complicated as to be meaning less to the public.

It is becoming regarded as one of the better ISDT events. Jan Krifka, one of the foremost authorities on the ISDT, told me he ranked the American event as one of the top five in his memory. He felt the terrain put together by Al Eames was the best he'd ever experi enced. For many years no European nation has had the guts to put together six individual loops of trail like Al did; they are all using the same sections more than once.

The policing system and the route marshals were superior and the Euro peans complained bitterly about it.

QUESTION: That's a good sign isn't it?

YOUNGBLOOD: Yes. When bitter com plaints came up in Madrid, Juan Soler Bulto said that this means that we should take a close look at an event that requires such careful policing, we should not complain about the Americans.

QUESTION: What grounds can anyone offer for a complaint that they are being watched? You can't say they are pre venting us from cheating. You can't get up before the FIM Congress and say "I'm not saying why, but the American route marshals are too good."

WIRWAHN: Cheating had become an> accepted part ot the ISV! because there never had been enough marshals to prevent it.

YOUNGBLOOD: That's right. It's not an argument you can defend.

QUESTION: Then a lot of the credit for the event must go to Al Eames.

YOUNGBLOOD: Al was responsible for most of the positive things. Al had absolutely no responsibility for the things that did collapse.

QUESTION: What were some of the serious problems?

YOUNGBLOOD: America, as basically neutral territory, served as a stage for some pretty nasty political disputes. We had problems the public will never know about. Very serious political prob lems that go far beyond motorcycling, a kind of ideological mini-war. Then there was the matter of the gate to the parc ferme being locked on Tuesday morn ing. There was a lot of criticism, espe cially from the British, about that, but it turned out that they had done exactly the same thing at the Scottish Six Days several years before. Then we chartered three airplanes and flew everybody over here. Americans get to the ISDT by hook or by crook, any way we can. We won't do that for the Europeans again. Our press corps was absolutely inade quate, but that went unnoticed because the computers weren't putting out the scores anyway.

QUESTION: It must have been pretty expensive.

YOUNGBLOOD: There are no financial rewards for anybody but advertisers, and there are damn few for them. The ISDT cost the AMA $300,000 to put on, not counting staff time. We didn't use any membership money for it. It was entirely paid for by sponsorships from Yamaha, Honda, Kawasaki, Husq varna, and Penton. Here and there we managed to recoup the rest of the money. Sponsorship will be a problem with the next ISDT. The industry is not as fat as it was two years ago, and the second time around is not going to be quite as big a deal. There is no way, for instance, that you can say that the event was worth $20,000 to Honda.

WIRWAHN: I agree with Ed that Honda or any of the other sponsors couldn't say that they put $20,000 in and got $50,000 back, but it is also true that they don't know how much they did get back. Everything the AMA does has a spin-off. Motorcycling is so multi faceted that it's very difficult to say exactly what the effect of doing any one thing really is. But I think it can be said without question that it had a beneficial effect.

QUESTION: Overall, then, it was a pretty worthwhile event.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 103

WIRWAHN: Yes, and there’s one other point that should be made. Being a novice at the time, I thought the ISDT was just an enduro that lasts six days. But when you get people from 17 different foreign countries and have last-minute lawsuits, and so on, you find that it is a very complex affair. I have never worked with a more dedicated group of people than the AMA staff and the motorcyclists of New England who helped put it on. Whether you were up at 4 a.m. getting out the results or working out in the field, no one shirked his responsibilities one single bit.

QUESTION: Do you think you’ll host the ISDT again?

YOUNGBLOOD: We are experiencing pressure from the Europeans now. Each time we go to an FIM meeting they bring it up and it’s no longer a casual or joking inquiry. They are starting to put the pressure on and ask about dates. In another year or so they’ll be strongly encouraging us or demanding.

QUESTION: Ed, earlier you told me that as general manager you do not become involved in competition, but the ISDT is surely competition, and you are clearly involved.

YOUNGBLOOD: The main thing I do not get involved in is professional Championship competition. Anything formative or related to the growth and overall welfare of the AMA, I am expected to oversee. I’m involved in the formation of the North American Trials Council and its National Amateur Championship series. I was involved in getting Camel to sponsor the professional circuit, but I haven’t been involved in professional racing.

QUESTION: Does that mean that observed trials, enduros, motocross and so on will never be part of professional championship racing?

YOUNGBLOOD: Not exactly. The highest level of motocross competition now is a strictly professional sport. But observed trials, amateur enduros, reliability trials and so on never will be professional. Professionalism is related to spectator gate, and I don’t know how you will ever draw crowds to these sports. Not crowds you can control or get admission from.

QUESTION: What’s on the horizon for motorcycles? What’s going to be the focus of interest in the next five years?>

WIR WAHN: The average person listening to us might think we’re pretty interested in land use and that we don’t think much about street bikes. But that’s not true. I’ve just briefly mentioned no-fault insurance, headlight legislation and rain grooving, but an area that is going to be of great importance to the street biker and the dirt rider is emissions control. The AMA feels that the industry is the one to decide about future technical regulations, whether to comply or not. But we get very concerned about ex post facto regulations like the ones the Environmental Protection Agency proposed a year ago that would have limited the use of twostroke motorcycles in summertime, daylight hours in certain areas like Los Angeles and New Jersey. These regulations concerned bikes that had already been sold, and we very vehemently objected to them. EPA withdrew its horns on that.

Another big unknown is fuel. If fuel gets scarce, motorcycles and mopeds might blossom as a means of transportation. When the energy crisis hit last year, this happened; the sales of motorcycles went up 111 percent in one month. But from the recreational standpoint it might have an adverse effect.

QUESTION: That’s interesting. If fuel prices go up, you suggest that the industry will benefit, but that motorcycles will become more utilitarian—less sporting.

YOUNGBLOOD: I have no doubt that some basic design philosophy questions are being considered by the manufacturers right now. They might go to three wheelers that can carry more people and more load, or they might go the way of Honda with little cars. The motorcycle as we have seen it in the last few years, a great big, extremely powerful, fourcylinder machine, doesn’t have much place in the future. Even if the country manages to stay prosperous, and the motorcycle continues to be primarily entertaining and sporting, it’s going to become a considerably tamer and saner machine.

QUESTION: Do you see motorcycles as bellwethers of other things that are happening in our culture? Does the motorcycle have historical significance in the larger context?

YOUNGBLOOD: That’s a provocative question. It occurs to me that one of the biggest problems directing the AMA is plotting the future of motorcycling and the industry. If someone could see a connection between motorcycling in the U.S. and some sort of historical or economic progress, if some of those connections could be made, we might know what our future is. But if it is related to our history or our culture, I don’t know anybody that has been bright enough to see how. [Öl

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

October 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

October 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

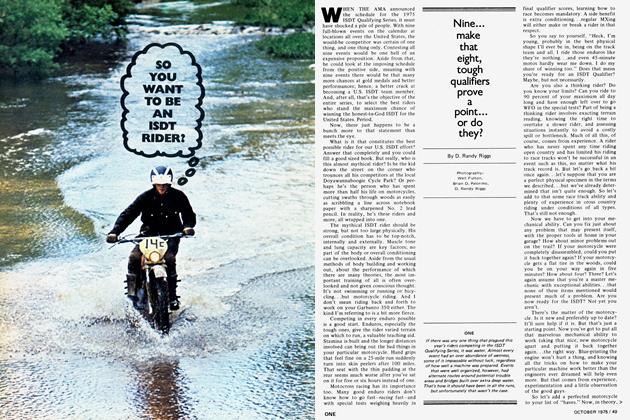

FeaturesSo You Want To Be An Isdt Rider?

October 1975 By D. Randy Riggs -

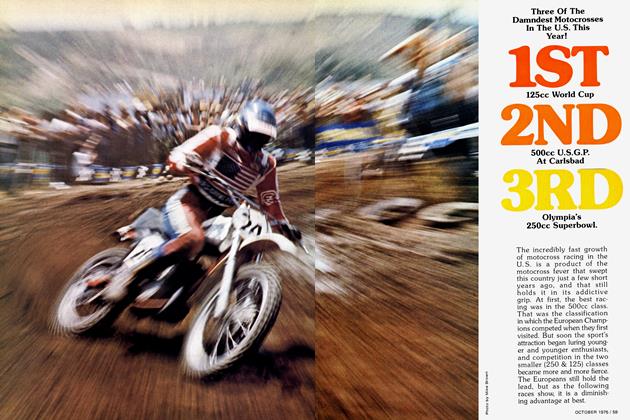

Special Competition Feature

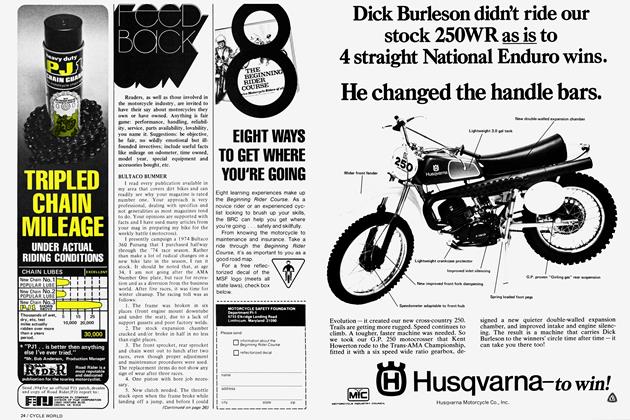

Special Competition FeatureThree of the Damndest Motocrosses In the U.S. This Year!

October 1975 -

Special Competition Feature

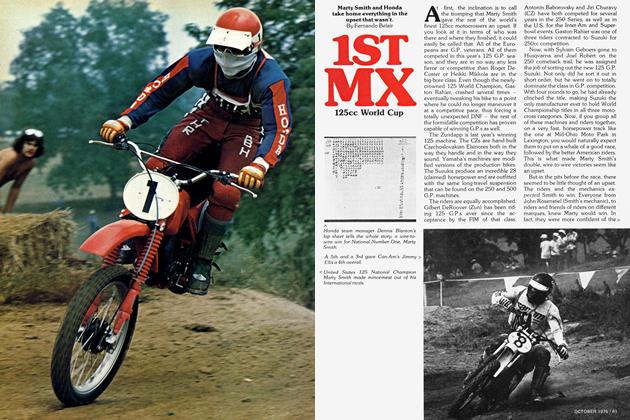

Special Competition Feature1st Mx 125cc World Cup

October 1975 By Fernando Belair