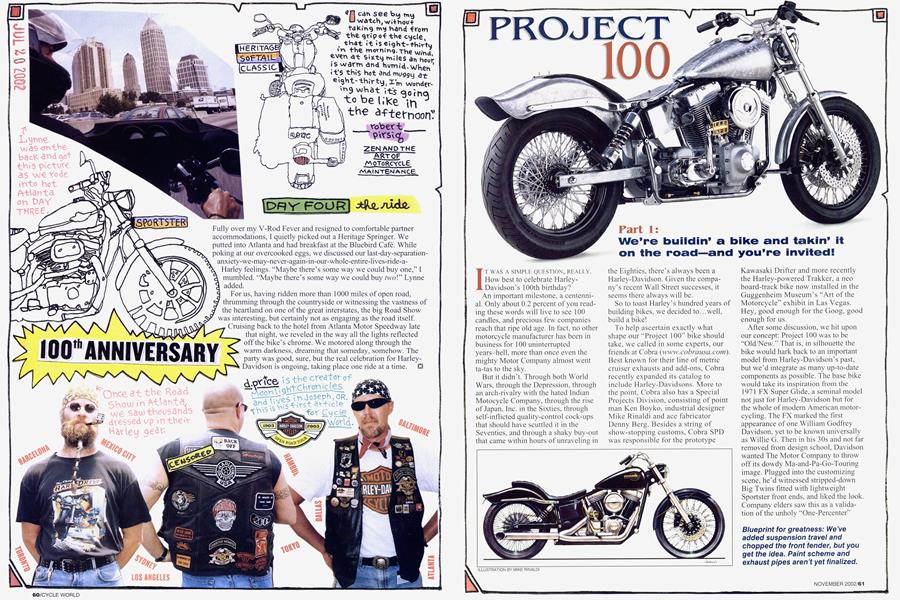

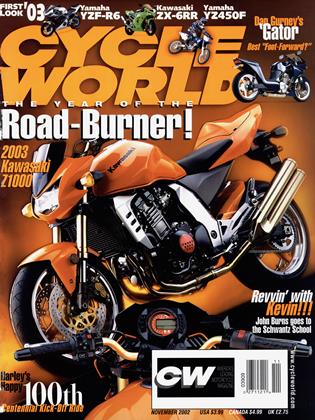

PROJECT 100

Part 1: We’re buildin’ a bike and fakin’ it on the road—and you’re invited!

IT WAS A SIMPLE QUESTION, REALLY. How best to celebrate Harley-Davidson’s 100th birthday? An important milestone, a centennial. Only about 0.2 percent of you reading these words will live to see 100 candles, and precious few companies reach that ripe old age. In fact, no other motorcycle manufacturer has been in business for 100 uninterrupted years-hell, more than once even the mighty Motor Company almost went ta-tas to the sky.

But it didn’t. Through both World Wars, through the Depression, through an arch-rivalry with the hated Indian Motocycle Company, through the rise of Japan, Inc. in the Sixties, through self-inflicted quality-control cock-ups that should have scuttled it in the Seventies, and through a shaky buy-out that came within hours of unraveling in the Eighties, there’s always been a Harley-Davidson. Given the company’s recent Wall Street successes, it seems there always will be.

So to toast Harley’s hundred years of building bikes, we decided to.. .well, build a bike!

To help ascertain exactly what shape our “Project 100” bike should take, we called in some experts, our friends at Cobra (www.cobrausa.com). Best known for their line of metric cruiser exhausts and add-ons, Cobra recently expanded its catalog to include Harley-Davidsons. More to the point, Cobra also has a Special Projects Division, consisting of point man Ken Boyko, industrial designer Mike Rinaldi and ace fabricator Denny Berg. Besides a string of show-stopping customs, Cobra SPD was responsible for the prototype

Kawasaki Drifter and more recently the Harley-powered Trakker, a neo board-track bike now installed in the Guggenheim Museum’s “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit in Las Vegas. Hey, good enough for the Goog, good enough for us.

After some discussion, we hit upon our concept: Project 100 was to be “Old/New.” That is, in silhouette the bike would hark back to an important model from Harley-Davidson’s past, but we’d integrate as many up-to-date components as possible. The base bike would take its inspiration from the 1971 FX Super Glide, a seminal model not just for Harley-Davidson but for the whole of modern American motorcycling. The FX marked the first appearance of one William Godfrey Davidson, yet to be known universally as Willie G. Then in his 30s and not far removed from design school, Davidson wanted The Motor Company to throw off its dowdy Ma-and-Pa-Go-Touring image. Plugged into the customizing scene, he’d witnessed stripped-down Big Twins fitted with lightweight Sportster front ends, and liked the look. Company elders saw this as a validation of the unholy “One-Percenter” outlaw lifestyle and dug in their heels.

“I had to do some heavy internal convincing,” said Willie G.

Having your name on the gas tank carries clout, though, and the Super Glide-yep, a stripped-down Big Twin fitted with lightweight Sportster front end-was bom. It was the first of the socalled “factory-customs,” what we now know as cmisers. Norton Hi-Riders and Kawasaki LTDs and Yamaha Midnight Specials would soon follow, but the Super Glide was first. In years to come, the bike’s wonky double-decker fiberglass tailsection would give way to a conventional fender, and disc brakes, mbber engine mounts and beltdrive would be added, but the style had been set. Today, about half of all HarleyDavidson models-and a fair number of competitors’ bikes-can trace their roots back to that ’71 FX.

So, just like Willie G., we started wit

a Duo-Glide frame, so-named because back in 1958 it was the first Harley to have dual (as in front and rear) suspension. Not trusting half-century-old steel, though, we ordered a replica Paucho frame through Drag Specialties-same geometry as stock but an all-welded affair rather than the brazed construction of the original.

Paucho’s rendition had another alteration we were sorely in need of, namely more room in the engine bay courtesy of dogleg downtubes. The extra inches were required because we intended to stuff the old frame full of new Twin Cam 88B crate motor. Old/new, get it?

That theme carries through to the running gear. Fork is a full-adjust Showa cartridge unit from the current Sportster Sport, complete with XL triple-clamps, headlight and trademark “eyebrow.” Out ^ back, a pair of traditional-looking Progressive 440 Series shocks carry the company’s impressive Inertia Active System technology. Front brakes and rotors are from Performance Machine; rear brake is a hydraulic drum from Custom Chrome, a dead-ringer for the old-style H-D binder. It’s a sprocketand-drum combo, which allows us to run a chain (“old”) rather than drivebelt, though it’ll be an O-ring type (“new”).

With the rear wheel’s tackle all grouped on the left, the right side becomes a showcase for our black-powdercoated Hallcraft rim and its chromed spokes-all 80 of ’em! “Old” necessitated the 19-inch front/18inch rear wheel sizes; “new” was taken care of by the self-balancing Hallcrafts (a sealed hoop of mercury is contained in the rim’s drop center), which are intended to run tubeless.

Paying homage to past customizers, we mounted a smoothed, 4.5-gallon Fat Bob fuel tank and a rear fender that takes its shape from the valanced front fenders old dressers used to run, trimmed to fit. Both are repro items from Drag Specialties.

So that’s it for the bare-metal mockup. Next installment, Project 100 will be wired, plumbed and makin’ noise.

Speaking of which, come help us raise the rafters. Next August our Centennial Super Glide will hit the road, bound for the 100th Homecoming in Milwaukee.

Our pals at Lotus Tours have laid out a great eight-day route from California-all backroads, no interstates-and arranged accommodations along the way for CW staffers and about 30 riders. For dates, details and pricing, contact Lotus at 312/951 -0031 ; www. lotustours.com. Should be fun, a great way of wishing Harley a happy 100th. And many more.

David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

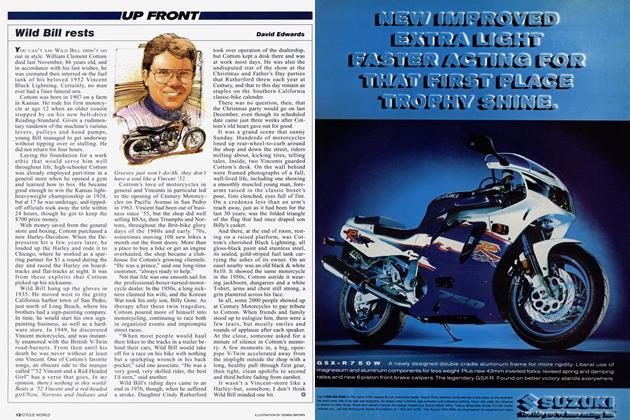

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Side of Speed

November 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Morning In Italy

November 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving In Harmony

November 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2002 -

Roundup

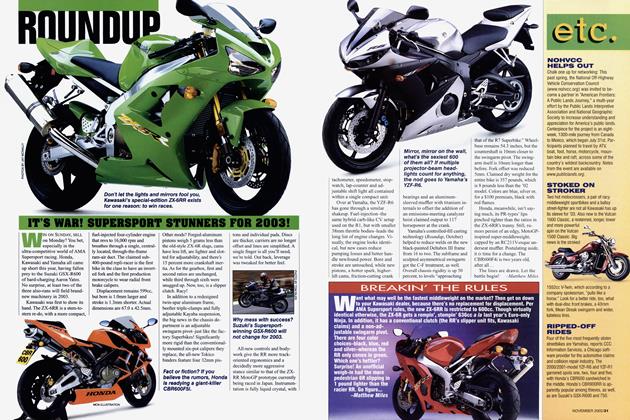

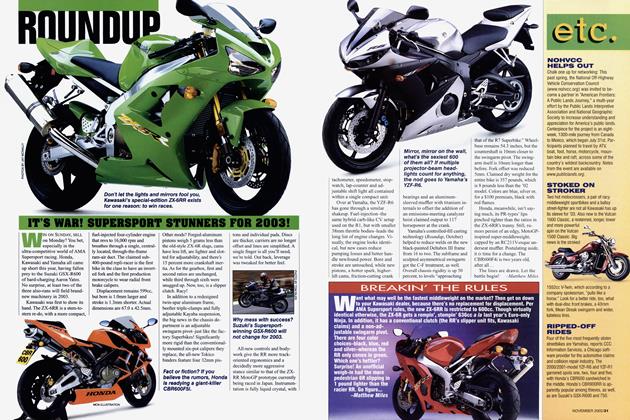

RoundupIt's War! Supersport Stunners For 2003!

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBreakin' the Rules

November 2002 By Matthew Miles