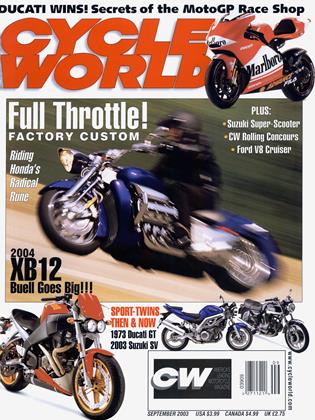

UP FRONT

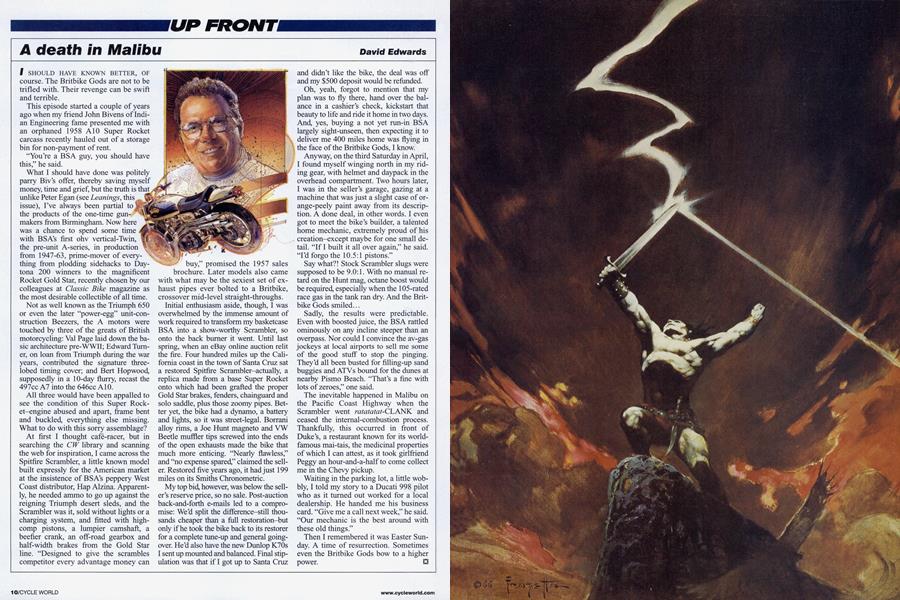

A death in Malibu

David Edwards

I SHOULD HAVE KNOWN BETTER, OF course. The Britbike Gods are not to be trifled with. Their revenge can be swift and terrible.

This episode started a couple of years ago when my friend John Bivens of Indian Engineering fame presented me with an orphaned 1958 A10 Super Rocket carcass recently hauled out of a storage bin for non-payment of rent.

“You’re a BSA guy, you should have this,” he said.

What I should have done was politely parry Biv’s offer, thereby saving myself money, time and grief, but the truth is that unlike Peter Egan (see Leanings, this issue), I’ve always been partial to the products of the one-time makers from Birmingham. Now here was a chance to spend some time with BSA’s first ohv vertical-Twin, the pre-unit A-series, in production from 1947-63, prime-mover of everything from plodding sidehacks to Daytona 200 winners to the magnificent Rocket Gold Star, recently chosen by our colleagues at Classic Bike magazine as the most desirable collectible of all time.

Not as well known as the Triumph 650 or even the later “power-egg” unit-construction Beezers, the A motors were touched by three of the greats of British motorcycling: Val Page laid down the basic architecture pre-WWII; Edward Turner, on loan from Triumph during the war years, contributed the signature threelobed timing cover; and Bert Hopwood, supposedly in a 10-day flurry, recast the 497cc A7 into the 646cc A10.

All three would have been appalled to see the condition of this Super Rocket-engine abused and apart, frame bent and buckled, everything else missing. What to do with this sorry assemblage?

At first I thought café-racer, but in searching the CW library and scanning the web for inspiration, I came across the Spitfire Scrambler, a little known model built expressly for the American market at the insistence of BSA’s peppery West Coast distributor, Hap Alzina. Apparently, he needed ammo to go up against the reigning Triumph desert sleds, and the Scrambler was it, sold without lights or a charging system, and fitted with highcomp pistons, a lumpier camshaft, a beefier crank, an off-road gearbox and half-width brakes from the Gold Star line. “Designed to give the scrambles competitor every advantage money can buy,” promised the 1957 sales brochure. Later models also came with what may be the sexiest set of exhaust pipes ever bolted to a Britbike, crossover mid-level straight-throughs.

Initial enthusiasm aside, though, I was overwhelmed by the immense amount of work required to transform my basketcase BSA into a show-worthy Scrambler, so onto the back burner it went. Until last spring, when an eBay online auction relit the fire. Four hundred miles up the California coast in the town of Santa Cruz sat a restored Spitfire Scrambler-actually, a replica made from a base Super Rocket onto which had been grafted the proper Gold Star brakes, fenders, chainguard and solo saddle, plus those zoomy pipes. Better yet, the bike had a dynamo, a battery and lights, so it was street-legal. Borrani alloy rims, a Joe Hunt magneto and VW Beetle muffler tips screwed into the ends of the open exhausts made the bike that much more enticing. “Nearly flawless,” and “no expense spared,” claimed the seller. Restored five years ago, it had just 199 miles on its Smiths Chronometrie.

My top bid, however, was below the seller’s reserve price, so no sale. Post-auction back-and-forth e-mails led to a compromise: We’d split the difference-still thousands cheaper than a full restoration-but only if he took the bike back to its restorer for a complete tune-up and general goingover. He’d also have the new Dunlop K70s I sent up mounted and balanced. Final stipulation was that if I got up to Santa Cruz and didn’t like the bike, the deal was off and my $500 deposit would be refunded.

Oh, yeah, forgot to mention that my plan was to fly there, hand over the balance in a cashier’s check, kickstart that beauty to life and ride it home in two days. And, yes, buying a not yet run-in BSA largely sight-unseen, then expecting it to deliver me 400 miles home was flying in the face of the Britbike Gods, I know.

Anyway, on the third Saturday in April, I found myself winging north in my riding gear, with helmet and daypack in the overhead compartment. Two hours later, I was in the seller’s garage, gazing at a machine that was just a slight case of orange-peely paint away from its description. A done deal, in other words. I even got to meet the bike’s builder, a talented home mechanic, extremely proud of his creation-except maybe for one small detail. “If I built it all over again,” he said. “I’d forgo the 10.5:1 pistons.”

Say what?! Stock Scrambler slugs were supposed to be 9.0:1. With no manual retard on the Hunt mag, octane boost would be required, especially when the 105-rated race gas in the tank ran dry. And the Britbike Gods smiled...

Sadly, the results were predictable. Even with boosted juice, the BSA rattled ominously on any incline steeper than an overpass. Nor could I convince the av-gas jockeys at local airports to sell me some of the good stuff to stop the pinging. They’d all been busted for filling-up sand buggies and AT Vs bound for the dunes at nearby Pismo Beach. “That’s a fine with lots of zeroes,” one said.

The inevitable happened in Malibu on the Pacific Coast Highway when the Scrambler went ratatataT-CLANK and ceased the internal-combustion process. Thankfully, this occurred in front of Duke’s, a restaurant known for its worldfamous mai-tais, the medicinal properties of which I can attest, as it took girlfriend Peggy an hour-and-a-half to come collect me in the Chevy pickup.

Waiting in the parking lot, a little wobbly, I told my story to a Ducati 998 pilot who as it turned out worked for a local dealership. He handed me his business card. “Give me a call next week,” he said. “Our mechanic is the best around with these old things.”

Then I remembered it was Easter Sunday. A time of resurrection. Sometimes even the Britbike Gods bow to a higher power.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

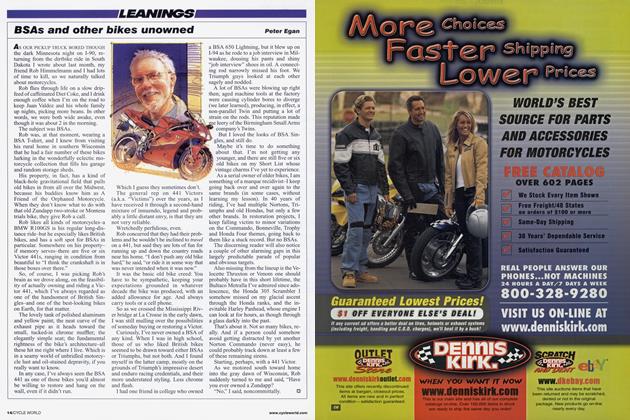

ColumnsLeanings

September 2003 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2003 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupKingpin Kick-Off

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBigger, Badder Road Star

September 2003 By Brian Catterson