TDC

Listening

KEVIN CAMERON

IT’S USEFUL TO HAVE EARS. YEARS AGO, a young man came to my shop with a Suzuki 500 Titan. He ran the engine and I heard a low-frequency series of thuds. I said, “Tools are in that box over there. Turn the petcock off, lay the thing on its side so you won’t have to drain the gearbox oil, then pull off the primary cover. Turn the engine and look at the primary gear on the clutch. You’ll find a chunk of aluminum wedged between two teeth somewhere.” I went back to whatever I was doing and he got on with his task.

A few minutes later, I heard an exclamation. “How’d you know that?” he said, looking at me as if I could see through aluminum.

“Those thuds it was making weren’t frequent enough to be happening at crankshaft speed, so the problem had to be on the slower-turning clutch gear. Now you have to figure out where that chunk of aluminum came from!”

After knocking the aluminum out from between the teeth with a pin punch and a small hammer, and then reassembling, the noise was gone. When you make such a diagnosis and it turns out to be right, your reputation as a wizard is made, even though you only applied the common sense that is available to us all.

There are wizards, but I’m not one of them. At the Dutch TT in 1981, I was talking with Erv Kanemoto in the paddock when one of the factory Yamaha 0W53 500s was started up. Erv held up his hand for silence, listening as the warmup continued. After a few seconds, he said, talking mostly to himself, “Okay, they’ve changed the Powervalve program. Or...maybe the compression.”

I could hear the sounds but not what they meant. When Erv was a very young man racing karts, he built and ran literally hundreds of engines, acquiring in the process an ear for the effects of changes to port timing, ignition timing and compression.

At MV Agusta’s old race shop, it is said that the fastest engines were built by a particular mechanic who set ignition timing not by use of degree wheel and timing light or by watching the torque scale on the dyno, but by ear. For him, an engine made a certain set of auditory signals when at its best, and he tuned to that.

In 2003, I went to Motegi for the Japanese MotoGP round. At that time, MotoGP was still tremendously novel, and people were ready to believe almost anything. (At a press briefing, a European journalist asked Honda engineer Kanaumi if hidden gyroscopes were being used to actively stabilize the RC211V). An official press release informed us that a controlled air leak was being used to “equalize pressures above and below” that machine’s pistons, thereby counteracting the upsetting effects of engine braking. I thought that would have to be a pretty big air leak. I walked to a comer where I could hear clearly, and it was immediately apparent that different strategies were in use. The Kawasakis were the only ones that sounded like four-strokes on closed throttle, popping and banging on the overrun. Honda’s engines were running smoothly all the way to the throttle-up point—no banging or irregular running. Ducatis were doing the same, as was one of the Yamahas. The other Yamaha sounded more like the Kawasaki. When I encountered Kenny Roberts in the paddock, I asked him what was going on.

“Come into my garage and I’ll show you.” The answer was what in F-l is called a “throttle kicker,” a motor-driven throttle positioner that the engine-control computer could use to apply just enough throttle to cancel any desired percentage of engine braking. That’s why I heard engines run all the way into the corner. This small revelation made nonsense of Honda’s “controlled air leak,” and when I asked Mr. Kanaumi if fuel were injected at the same time, he admitted that it was.

In automobile diagnostics, the crunching of a failing front wheel bearing could easily be distinguished from the somewhat similar ticking of a universal joint about to give up. How? Like the thud in

the Suzuki Titan, speed tells the story: The U-joint noise happens about three times more often than the wheel-bearing crunch (this speed relationship is whatever the axle ratio happens to be). Today, such skills are supposed to be unnecessary. Just plug the console into the OBD port and all problems are expected to appear on the screen. No need for thought, analysis or experience. But listening still gives information that cannot be gleaned any other way, and, in fact, it is fun.

In earlier, less-electronic times, a good listener could learn something about the cam choices of the various teams. The natural popping and banging of a four-stroke decelerating on closed throttle depends on valve overlap, which can admit exhaust to the cylinder. This dilutes the fresh charge coming from the intake system, perhaps enough to cause irregular firing, sometimes with ignition of passed-through charge that has accumulated in the exhaust pipe. The more overlap, the more pops and bangs.

Stand at a corner and make a mental note of where the various riders begin to move the throttle. Listen for the way the engine takes up the load. Is it smooth or is it irregular and jerky? Turn 2 at the (former) Loudon national in New Hampshire provided a demonstration. Anthony Gobert’s Ducati came on smoothly from zero throttle, allowing him to start opening up when still well over on the sides of his tires. Mat Mladin’s Yoshimura Suzuki, still in its formative years with fuel injection, came on with something of a jerk, obliging him to delay throttle-up. In the present era, this situation has received the most detailed refinement from electronic aids. And so it should: Early throttle-up is a crucial element of a quick lap time.

We have all heard the irregular machine-gun sound of an engine whose traction-control system is reducing torque by cylinder cuts. Such a system may have three different modes of operation, the first two of which are inaudible. First, small power reductions may be made by electronic ignition retard, and second, in a throttle-by-wire system, the computer may cut power by throttle movement. Only if very rapid response is needed would ignition cuts be used. And we do hear these.

When there is a radical change—such as Honda’s introduction of “Big Bang” close firing order on its two-strokes in 1992 or Ducati’s 2005 effort to conserve fuel by automatically declutching and idling the engine into corners—we often get the first evidence from our ears.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

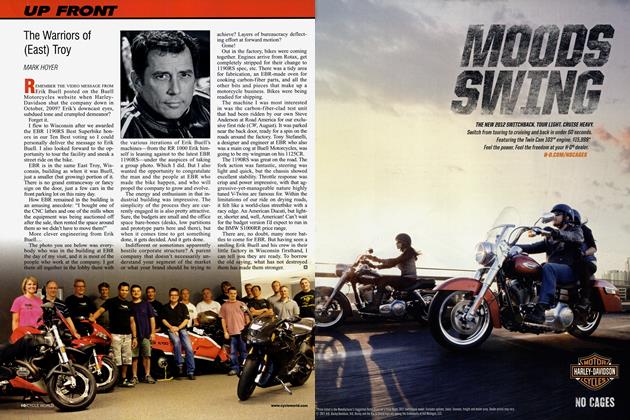

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

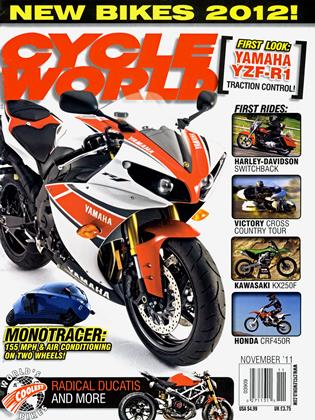

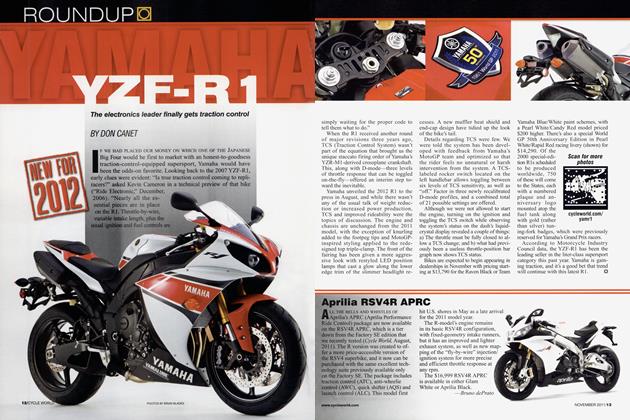

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet