Made in Europe

UP FRONT

David Edwards

WITH PENCIL POISED ABOVE NOTEPAD, I pressed the BMW engineer about the new R1100RS. It was one day before the Boxer Twin’s official unveiling, and I was trying to get a jump on the rest of the journalists on hand for the bike’s introduction.

“So, what’s the frame made from, steel or aluminum?” I asked.

“Well, actually, there is no frame...” came the reply.

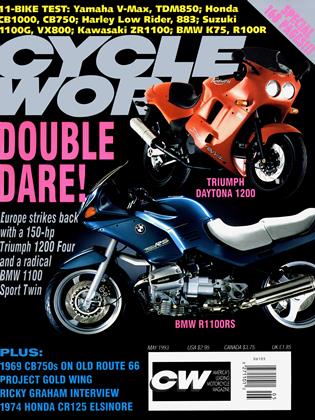

That was my first tip-off that Europe’s latest motorcycle was going to be something special. You can read all about it in Technical Editor Kevin Cameron’s analysis elsewhere in this issue. Eight years in the making, at a development cost of some $100 million, the R1100 will play a major role in BMW’s future. As one spokesman put it, “BMW is the Boxer, the Boxer is BMW..we expect it will take us successfully into the next millennium.” The company hasn’t exactly bet the farm on this new bike, but it’s fair to say that the back 40 is heavily in hock.

BMW isn’t the only European firm in a gambling mood these days, either. In fact, as European Correspondent Alan Cathcart expressed in his January report on last fall’s Cologne Show, 1993 could well be subtitled “The Year of the European Bike.” Most years, the Japanese Big Four steal the show, but not this time. Yes, Yamaha’s GTS 1000, with American designer James Parker’s RADD-derived alternate front end, caused quite a stir, and the two Kawasaki KLX650 Singles were somewhat of a surprise, but it was the Euro bike-makers that drew the biggest oohs and ahhs from Cologne show-goers.

Ducati pulled the wraps off its lovely little Supermono 502cc Single and its “II Monstro” M900 super standard. Triumph showed its revised line of 900cc Triples and 1200cc Fours. Tiny Bimota, which kicked off the alternate front suspension movement two years ago, had an even spacier Tesi 1D and a sexy, spidery DB2. BMW whetted everyone’s appetite by showing only the new Type R259 Boxermotor and leaving the rest of the RI 100RS to the imagination. For the first time in years, most of the excitement at Cologne was with the European manufacturers.

Our man Cathcart braved the chilly rain and slickened roads of wintertime England to bring back this issue’s riding impression on one of those excitement-makers, the Triumph Daytona. Now, you and I will have no argument if you allege that the 1993 Daytona 1200 doesn’t exude the same elegance and panache as a 1970 Bonneville 650. But it’s nice to have Triumph back, and you’ve got to like the fact that the company has thumbed its corporate nose at the mamby-pambs who would strangle every bike down to 100 horsepower. At a claimed 147 horsepower, the Daytona is the most powerful streetbike Europe has ever made.

Before the old Triumph company died of massive internal hemorrhaging in 1983, one of its slogans was “World’s Fastest Motorcycle.” Ten years later, against all odds, it may be time to dust off that motto.

Ducati’s M900 II Monstro won’t be going after any speed titles, but it is interesting. And illuminating. Much has been made recently about the reemergence of standard-style bikes (see “Super Standards” in this issue), but most of these have a decidedly retro flavor, exemplified by Kawasaki’s ZR1100 and Honda’s CB1000, both of which are well-done caricatures of early-’70s AMA Superbike racers. The reason for this is simple: In Japan, these retro-standards, in a variety of engine sizes, are all the rage and selling like rice cakes, even outpacing the sales of sportbikes in some cc classes.

The M900, scheduled for release soon, is different. With a tubular spaceframe wrapped around its air-and-oilcooled V-Twin, with an upside-down fork, with a single-shock, raising-ratelinkage rear suspension, with contemporary styling, the II Monstro is a standard that looks forward, not backward in time. What Honda and Kawasaki seem to have forgotten is that when those archetypal Japanese standards, the CB750 and the Z-l, bowed 20 years ago, they were leading-edge stuff, jam-packed with the highest tech and the highest performance of the era. The closest Japan has come to viable, modern standards is the now-defunct 400cc Honda CB-1 and the current Suzuki Bandit 400, both great fun to ride-and both too small to attract a serious following in America.

As motorcycling approaches the year 2000, there is good news and bad. New-bike sales are up. Public acceptance is up. Seemingly, you can’t open a mainstream magazine without seeing a bike used as a prop in an ad. In CWs own little corner of the sport, we’re having our most successful year in a long time, thanks to you, our readers. Circulation is up to an average of 360,000 per month, the largest of any motorcycle publication in the world, and 100,000 more than our nearest U.S. competitor. Providing further evidence that more and more people are becoming interested in motorcycling, CWs newsstand sales are up 40 percent since 1991, and for the second year in a row, Cycle World has been named as one of America’s “10 Hottest Magazines” by Capell’s Circulation Report, beating out such publishing stalwarts as Money, People, Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and Vanity Fair. The issue you hold in your hands, at 168 pages, is our biggest in 11 years.

Interest may be high, but challenges remain. Not enough young riders are taking up motorcycling. There are gaps, both in functionality and in price, in some bike-makers’ lineups. Whacko environmentalists aren’t about to go away, and there is no shortage of dogooders attempting to pass legislation for the sole purpose of protecting us from ourselves and our pastimes. Now is the time for everyone involved in the sport-manufacturers, dealers, the aftermarket, professional organizations, riders themselves-to step up and make a difference.

Europe is doing its part.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsElectra Glide Report Card

May 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAnatomy of A Spark

May 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Yamaha Sportbike?

May 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupTy250z: One Trick Trials Bike

May 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Japan-Italy Connection

May 1993 By Matthew Miles