TRIUMPH TRIO: Variations aTheme

A Triumph that never was

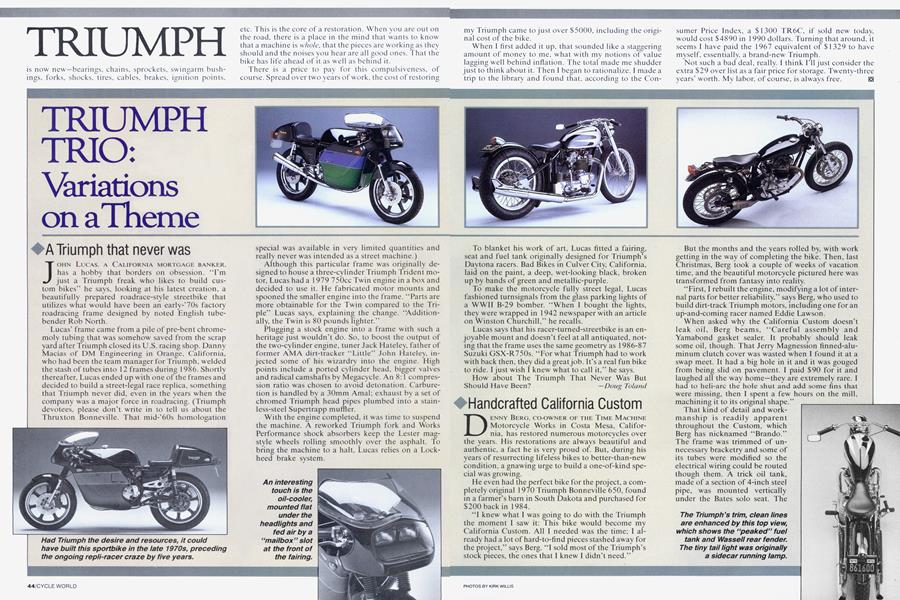

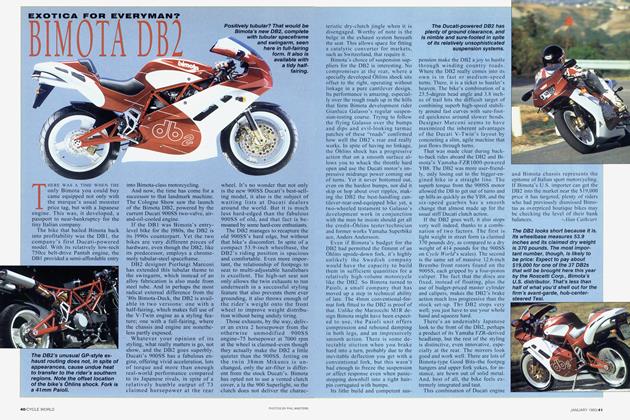

JOHN LUCAS, A CALIFORNIA MORTGAGE BANKER. has a hobby that borders on obsession. “I’m just a Triumph freak who likes to build custom bikes” he says, looking at his latest creation, a beautifully prepared roadrace-style streetbike that utilizes what would have been an early-’70s factory roadracing frame designed by noted English tubebender Rob North.

Lucas’ frame came from a pile of pre-bent chromemoly tubing that was somehow saved from the scrap yard after Triumph closed its U.S. racing shop. Danny Macias of DM Engineering in Orange, California, who had been the team manager for Triumph, welded the stash of tubes into 12 frames during 1986. Shortly thereafter, Lucas ended up with one of the frames and decided to build a street-legal race replica, something that Triumph never did, even in the years when the company was a major force in roadracing. (Triumph devotees, please don’t write in to tell us about the Thruxton Bonneville. That mid-’60s homologation special was available in very limited quantities and really never was intended as a street machine.)

Although this particular frame was originally designed to house a three-cylinder Triumph Trident motor, Lucas had a 1979 750cc Twin engine in a box and decided to use it. He fabricated motor mounts and spooned the smaller engine into the frame. “Parts are more obtainable for the Twin compared to the Triple” Lucas says, explaining the change. “Additionally, the Twin is 80 pounds lighter.”

Plugging a stock engine into a frame with such a heritage just wouldn't do. So, to boost the output of the two-cylinder engine, tuner Jack Hateley, father of former AMA dirt-tracker “Little” John Hateley, injected some of his wizardry into the engine. High points include a ported cylinder head, bigger valves and radical camshafts by Megacycle. An 8: l compression ratio was chosen to avoid detonation. Carburetion is handled by a 30mm Amal; exhaust by a set of chromed Triumph head pipes plumbed into a stainless-steel Supertrapp muffler.

With the engine completed, it was time to suspend the machine. A reworked Triumph fork and Works Performance shock absorbers keep the Lester magstyle wheels rolling smoothly over the asphalt. To bring the machine to a halt, Lucas relies on a Lockheed brake system. To blanket his work of art, Lucas fitted a fairing, seat and fuel tank originally designed for Triumph’s Daytona racers. Bad Bikes in Culver City, California, laid on the paint, a deep, wet-looking black, broken up by bands of green and metallic-purple. The frame was trimmed of unnecessary bracketry and some of its tubes were modified so the electrical wiring could be routed though them. A trick oil tank, made of a section of 4-inch steel pipe, was mounted vertically under the Bates solo seat. The stock rear hub was strengthened, then mated to a ’64 brake drum, used because it’s a cleaner design than the later Triumph drums.

To make the motorcycle fully street legal, Lucas fashioned turnsignals from the glass parking lights of a WWII B-29 bomber. “When I bought the lights, they were wrapped in 1942 newspaper with an article on Winston Churchill,” he recalls.

Lucas says that his racer-turned-streetbike is an enjoyable mount and doesn’t feel at all antiquated, noting that the frame uses the same geometry as 1986-87 Suzuki GSX-R750s. “For what Triumph had to work with back then, they did a great job. It’s a real fun bike to ride. I just wish I knew what to call it,” he says.

How about The Triumph That Never Was But Should Have Been? —Doug Toland

Handcrafted California Custom

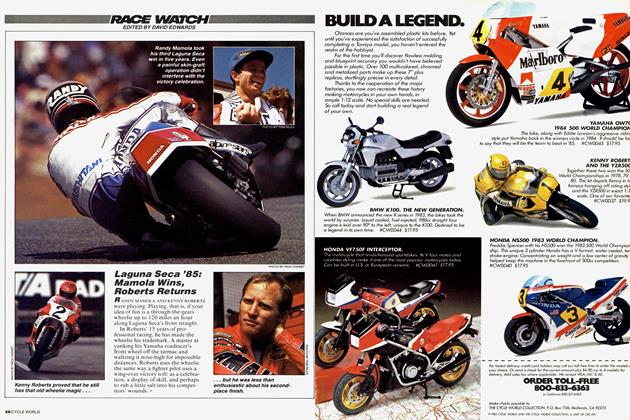

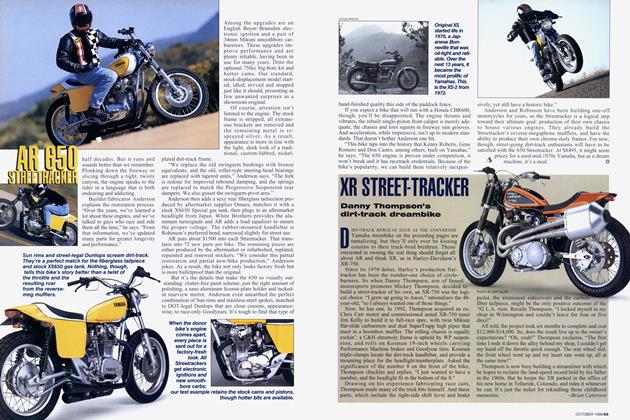

DENNY BERG, CO-OWNER OF THE TIME MACHINE Motorcycle Works in Costa Mesa, California, has restored numerous motorcycles over the years. His restorations are always beautiful and authentic, a fact he is very proud of. But, during his years of resurrecting lifeless bikes to better-than-new condition, a gnawing urge to build a one-of-kind special was growing.

He even had the perfect bike for the project, a completely original 1970 Triumph Bonneville 650, found in a farmer’s barn in South Dakota and purchased for $200 back in 1984.

“I knew what I was going to do with the Triumph the moment I saw it; This bike would become my California Custom. All I needed was the time; I already had a lot of hard-to-find pieces stashed away for the project,” says Berg. “I sold most of the Triumph’s stock pieces, the ones that I knew I didn’t need.” But the months and the years rolled by, with work getting in the way of completing the bike. Then, last Christmas, Berg took a couple of weeks of vacation time, and the beautiful motorcycle pictured here was transformed from fantasy into reality.

“First, I rebuilt the engine, modifying a lot of internal parts for better reliability,” says Berg, who used to build dirt-track Triumph motors, including one for an up-and-coming racer named Eddie Lawson.

When asked why the California Custom doesn’t leak oil, Berg beams, “Careful assembly and Yamabond gasket sealer. It probably should leak some oil, though. That Jerry Magnession finned-aluminum clutch cover was wasted when I found it at a swap meet. It had a big hole in it and it was gouged from being slid on pavement. I paid $90 for it and laughed all the way home—they are extremely rare. I had to heli-arc the hole shut and add some fins that were missing, then I spent a few hours on the mill, machining it to its original shape.”

That kind of detail and workmanship is readily apparent throughout the Custom, which Berg has nicknamed “Brando.”

A welded-on Santee hardtail subframe, a spool front hub (there’s no front brake to disrupt the bike’s clean lines), Harley fishtail mufflers, of all things, and Franks fork tubes, shortened a couple of inches, give the bike just the appearance Berg wanted.

“I spent a lot of time just looking at this bike from different angles,” says Berg, “I wanted each component to flow into a sleek, smooth motorcycle. I think I’ve accomplished that.”

And, indeed, he has. This bike is like a finely sculptured art form, a rare thing to keep and cherish for many years. But, surprisingly, Berg has the California Custom up for sale. How can he part with a motorcycle this special, one that has fulfilled a desire that had been growing for so long?

“No problem,” says Berg. “Once the bike was completed right down to the last detail, I sat down and spent some time looking at it, then moved on to the next project.” —Ron Griewe

As American as Ascot Park

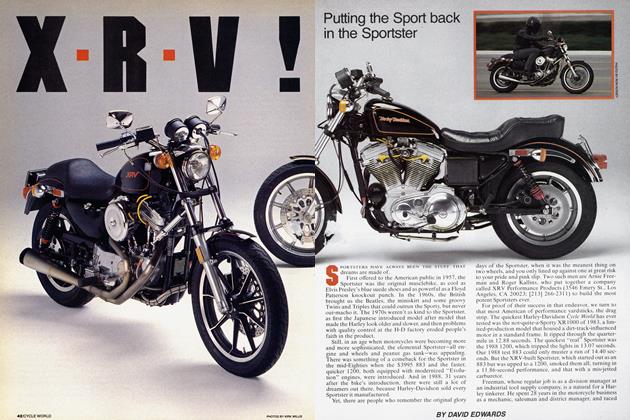

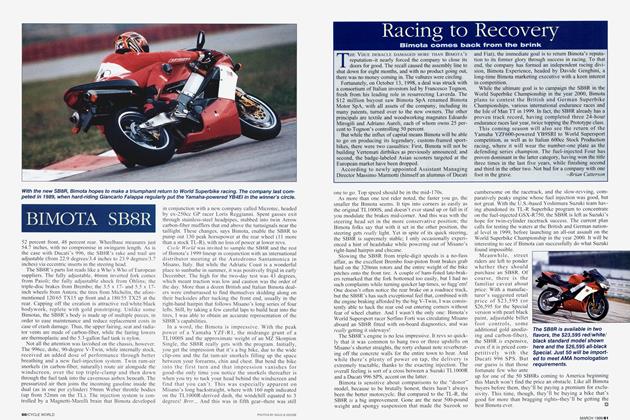

THE BIKE YOU SEE HERE, A STREET-LEGAL TT Triumph, rose, Phoenix-like, from the ashes of a bygone racing career.

Its builder, Sparky Edmonston, found out about a widow who had a two-car garage chock full of Triumph race parts, the legacy of a time when her husband and son built and raced the British Twins on the rough-and-tumble miles, half-miles and TTs of the 1970s California dirt-track circuit. Untouched for a decade, the garage contained three complete racebikes and parts “stuck all over the place, all the normal stuff a race guy collects over the years,” says Edmonston. Now in the movie stunt trade, Edmonston is a former racer who went on to some fame as tuner, wrenching Ricky Graham’s Honda to two grand national championships. He and film producer Steve Perry bought the parts, the deal being that they would sell what they could and build personal bikes out of the rest.

Perry’s bike would be built first, although when he first saw the raw materials, he was more than a little skeptical. “Ed taken all the bikes apart and had everything in one big pile so I could pick the best pieces,” says Edmonston. “Steve’s freaking out because all he sees is a bunch of ugly, rusty parts covered with Ascot dirt. He couldn’t visualize what they’d become.”

What they became a year-and-a-half and some 300 hours of Edmonston’s labor later was this motorcycle, beautiful and black, with a “TT-bike look, but modernized so it could be ridden everyday on the street if needed,” says Edmonston. Authentic flat-track pieces include the Trackmaster frame (with appropriate hangers and brackets for the street-legal equipment welded on by C&J Frames), Ceriani fork,

Barnes wheels, Hurst/Airheart brakes and an Eddie Mulder seat. The engine is a short-rod, five-speed 1979 model that’s been converted back to right-side shifting because Perry, a long-time Triumph rider, wanted it that way.

Modernity comes by way of Works Performance rear shocks, Japanese hand controls and brake master cylinders and, most tasty of all, an ultra-lightweight titanium exhaust system, made up as a favor by Edmonston’s long-time friend, super-tuner Rob Muzzy.

Edmonston is pleased with the way the Triumph turned out, though he knows many people won’t understand why he put so much time and effort into a non-standard bike. “The people that ‘know,’ say, ‘Geez, that’s a bitchin' motorcycle,”’ explains Edmonston with justifiable pride.

As for the on~e-skeptic~1 owner of the TT Tri umph? Well, he's already turned down an offer of $13,000 for the bike. -David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFathers, Sons And Motorcycles

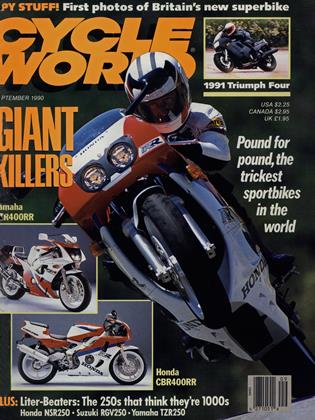

SEPTEMBER 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990