LEANINGS

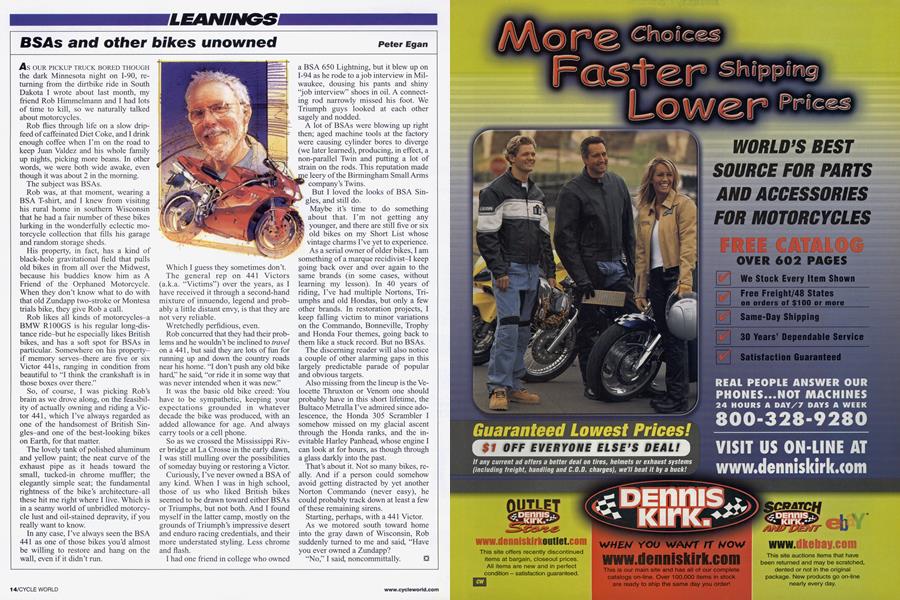

BSAs and other bikes unowned

Peter Egan

As OUR PICKUP TRUCK BORED THOUGH the dark Minnesota night on I-90, returning from the dirtbike ride in South Dakota I wrote about last month, my friend Rob Himmelmann and I had lots of time to kill, so we naturally talked about motorcycles.

Rob flies through life on a slow dripfeed of caffeinated Diet Coke, and I drink enough coffee when I’m on the road to keep Juan Valdez and his whole family up nights, picking more beans. In other words, we were both wide awake, even though it was about 2 in the morning.

The subject was BSAs.

Rob was, at that moment, wearing a BSA T-shirt, and I knew from visiting his rural home in southern Wisconsin that he had a fair number of these bikes lurking in the wonderfully eclectic motorcycle collection that fills his garage and random storage sheds.

His property, in fact, has a kind of black-hole gravitational field that pulls old bikes in from all over the Midwest, because his buddies know him as A Friend of the Orphaned Motorcycle. When they don’t know what to do with that old Zundapp two-stroke or Montesa trials bike, they give Rob a call.

Rob likes all kinds of motorcycles-a BMW R100GS is his regular long-distance ride-but he especially likes British bikes, and has a soft spot for BSAs in particular. Somewhere on his propertyif memory serves-there are five or six Victor 441s, ranging in condition from beautiful to “I think the crankshaft is in those boxes over there.”

So, of course, I was picking Rob’s brain as we drove along, on the feasibility of actually owning and riding a Victor 441, which I’ve always regarded as one of the handsomest of British Singles-and one of the best-looking bikes on Earth, for that matter.

The lovely tank of polished aluminum and yellow paint; the neat curve of the exhaust pipe as it heads toward the small, tucked-in chrome muffler; the elegantly simple seat; the fundamental rightness of the bike’s architecture-all these hit me right where I live. Which is in a seamy world of unbridled motorcycle lust and oil-stained depravity, if you really want to know.

In any case, I’ve always seen the BSA 441 as one of those bikes you’d almost be willing to restore and hang on the wall, even if it didn’t run. Which I guess they sometimes don’t.

The general rep on 441 Victors (a.k.a. “Victims”) over the years, as I have received it through a second-hand mixture of innuendo, legend and probably a little distant envy, is that they are not very reliable.

Wretchedly perfidious, even.

Rob concurred that they had their problems and he wouldn’t be inclined to travel on a 441, but said they are lots of fun for running up and down the country roads near his home. “I don’t push any old bike hard,” he said, “or ride it in some way that was never intended when it was new.”

It was the basic old bike creed: You have to be sympathetic, keeping your expectations grounded in whatever decade the bike was produced, with an added allowance for age. And always carry tools or a cell phone.

So as we crossed the Mississippi River bridge at La Crosse in the early dawn, I was still mulling over the possibilities of someday buying or restoring a Victor.

Curiously, I’ve never owned a BSA of any kind. When I was in high school, those of us who liked British bikes seemed to be drawn toward either BSAs or Triumphs, but not both. And I found myself in the latter camp, mostly on the grounds of Triumph’s impressive desert and enduro racing credentials, and their more understated styling. Less chrome and flash.

I had one friend in college who owned a BSA 650 Lightning, but it blew up on 1-94 as he rode to a job interview in Milwaukee, dousing his pants and shiny “job interview” shoes in oil. A connecting rod narrowly missed his foot. We Triumph guys looked at each other sagely and nodded.

A lot of BSAs were blowing up right then; aged machine tools at the factory were causing cylinder bores to diverge (we later learned), producing, in effect, a non-parallel Twin and putting a lot of strain on the rods. This reputation made e leery of the Birmingham Small Arms company’s Twins.

But I loved the looks of BSA Singles, and still do.

Maybe it’s time to do something about that. I’m not getting any younger, and there are still five or six old bikes on my Short List whose vintage charms I’ve yet to experience. As a serial owner of older bikes, I am something of a marque recidivist-I keep going back over and over again to the same brands (in some cases, without learning my lesson). In 40 years of riding, I’ve had multiple Nortons, Triumphs and old Hondas, but only a few other brands. In restoration projects, I keep falling victim to minor variations on the Commando, Bonneville, Trophy and Honda Four themes, going back to them like a stuck record. But no BSAs.

The discerning reader will also notice a couple of other alarming gaps in this largely predictable parade of popular and obvious targets.

Also missing from the lineup is the Velocette Thruxton or Venom one should probably have in this short lifetime, the Bultaco Metralla I’ve admired since adolescence, the Honda 305 Scrambler I somehow missed on my glacial ascent through the Honda ranks, and the inevitable Harley Panhead, whose engine I can look at for hours, as though through a glass darkly into the past.

That’s about it. Not so many bikes, really. And if a person could somehow avoid getting distracted by yet another Norton Commando (never easy), he could probably track down at least a few of these remaining sirens.

Starting, perhaps, with a 441 Victor.

As we motored south toward home into the gray dawn of Wisconsin, Rob suddenly turned to me and said, “Have you ever owned a Zundapp?

“No,” I said, noncommittally. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 2003 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2003 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupKingpin Kick-Off

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBigger, Badder Road Star

September 2003 By Brian Catterson