TDC

Four father

Kevin Cameron

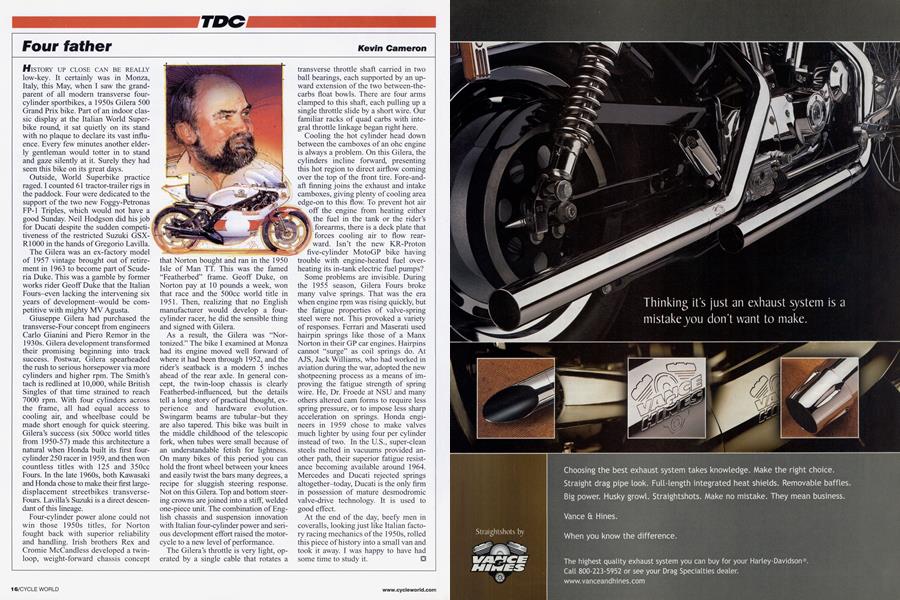

HISTORY UP CLOSE CAN BE REALLY low-key. It certainly was in Monza, Italy, this May, when I saw the grand-parent of all modern transverse four-cylinder sportbikes, a 1950s Gilera 500 Grand Prix bike. Part of an indoor classic display at the Italian World Superbike round, it sat quietly on its stand with no plaque to declare its vast influence. Every few minutes another elderly gentleman would totter in to stand and gaze silently at it. Surely they had seen this bike on its great days.

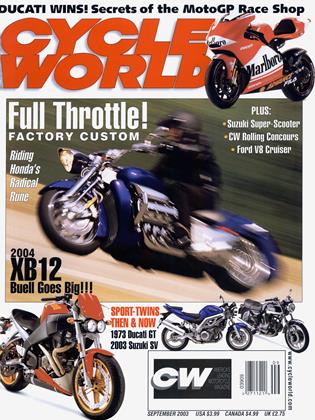

Outside, World Superbike practice raged. I counted 61 tractor-trailer rigs in the paddock. Four were dedicated to the support of the two new Foggy-Petronas FP-1 Triples, which would not have a good Sunday. Neil Hodgson did his job for Ducati despite the sudden competitiveness of the restricted Suzuki GSXR1000 in the hands of Gregorio Lavilla.

The Gilera was an ex-factory model of 1957 vintage brought out of retirement in 1963 to become part of Scuderia Duke. This was a gamble by former works rider Geoff Duke that the Italian Fours-even lacking the intervening six years of development-would be competitive with mighty MV Agusta.

Giuseppe Gilera had purchased the transverse-Four concept from engineers Carlo Gianini and Piero Remor in the 1930s. Gilera development transformed their promising beginning into track success. Postwar, Gilera spearheaded the rush to serious horsepower via more cylinders and higher rpm. The Smith’s tach is redlined at 10,000, while British Singles of that time strained to reach 7000 rpm. With four cylinders across the frame, all had equal access to cooling air, and wheelbase could be made short enough for quick steering. Gilera’s success (six 500cc world titles from 1950-57) made this architecture a natural when Honda built its first fourcylinder 250 racer in 1959, and then won countless titles with 125 and 350cc Fours. In the late 1960s, both Kawasaki and Honda chose to make their first largedisplacement streetbikes transverseFours. Lavilla’s Suzuki is a direct descendant of this lineage.

Four-cylinder power alone could not win those 1950s titles, for Norton fought back with superior reliability and handling. Irish brothers Rex and Cromie McCandless developed a twinloop, weight-forward chassis concept

a

that Norton bought and ran in the 1950 Isle of Man TT. This was the famed “Featherbed” frame. Geoff Duke, on Norton pay at 10 pounds a week, won that race and the 500cc world title in 1951. Then, realizing that no English manufacturer would develop a fourcylinder racer, he did the sensible thing and signed with Gilera.

As a result, the Gilera was “Nortonized.” The bike I examined at Monza had its engine moved well forward of where it had been through 1952, and the rider’s seatback is a modem 5 inches ahead of the rear axle. In general concept, the twin-loop chassis is clearly Featherbed-influenced, but the details tell a long story of practical thought, experience and hardware evolution. Swingarm beams are tubular-but they are also tapered. This bike was built in the middle childhood of the telescopic fork, when tubes were small because of an understandable fetish for lightness. On many bikes of this period you can hold the front wheel between your knees and easily twist the bars many degrees, a recipe for sluggish steering response. Not on this Gilera. Top and bottom steering crowns are joined into a stiff, welded one-piece unit. The combination of English chassis and suspension innovation with Italian four-cylinder power and serious development effort raised the motorcycle to a new level of performance.

The Gilera’s throttle is very light, operated by a single cable that rotates a

transverse throttle shaft carried in two ball bearings, each supported by an upward extension of the two between-thecarbs float bowls. There are four arms clamped to this shaft, each pulling up a single throttle slide by a short wire. Our familiar racks of quad carbs with integral throttle linkage began right here.

Cooling the hot cylinder head down between the camboxes of an ohc engine is always a problem. On this Gilera, the cylinders incline forward, presenting this hot region to direct airflow coming over the top of the front tire. Fore-andaft finning joins the exhaust and intake camboxes, giving plenty of cooling area edge-on to this flow. To prevent hot air off the engine from heating either the fuel in the tank or the rider’s forearms, there is a deck plate that forces cooling air to flow rearward. Isn’t the new KR-Proton five-cylinder MotoGP bike having trouble with engine-heated fuel overheating its in-tank electric fuel pumps?

Some problems are invisible. During the 1955 season, Gilera Fours broke many valve springs. That was the era when engine rpm was rising quickly, but the fatigue properties of valve-spring steel were not. This provoked a variety of responses. Ferrari and Maserati used hairpin springs like those of a Manx Norton in their GP car engines. Hairpins cannot “surge” as coil springs do. At AJS, Jack Williams, who had worked in aviation during the war, adopted the new shotpeening process as a means of improving the fatigue strength of spring wire. He, Dr. Froede at NSU and many others altered cam forms to require less spring pressure, or to impose less sharp acceleration on springs. Honda engineers in 1959 chose to make valves much lighter by using four per cylinder instead of two. In the U.S., super-clean steels melted in vacuums provided another path, their superior fatigue resistance becoming available around 1964. Mercedes and Ducati rejected springs altogether-today, Ducati is the only firm in possession of mature desmodromic valve-drive technology. It is used to good effect.

At the end of the day, beefy men in coveralls, looking just like Italian factory racing mechanics of the 1950s, rolled this piece of history into a small van and took it away. I was happy to have had some time to study it. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 2003 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 2003 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2003 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupKingpin Kick-Off

September 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBigger, Badder Road Star

September 2003 By Brian Catterson