Convention, unconvention

TDC

Kevin Cameron

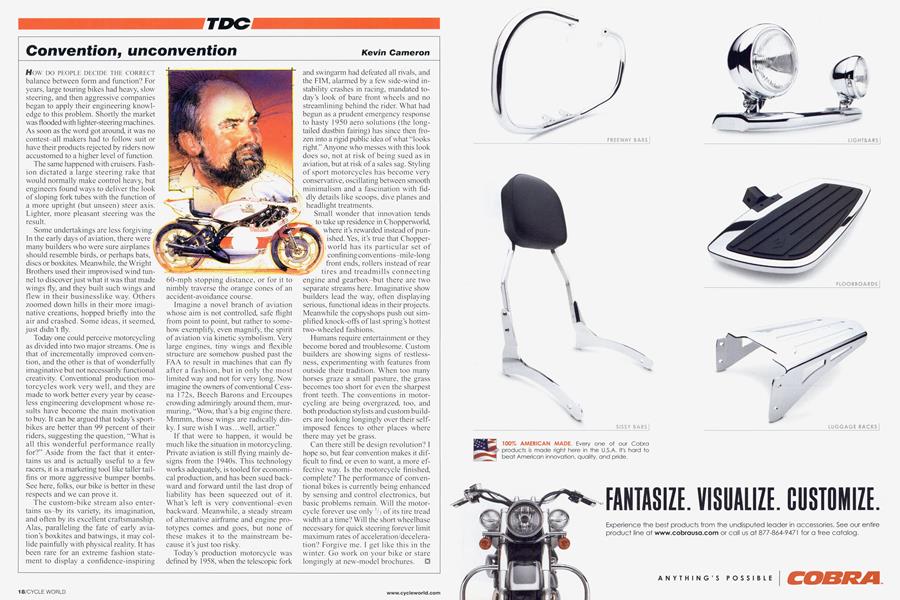

How DO PEOPLE DECIDE THE CORRECT balance between form and function? For years, large touring bikes had heavy, slow steering, and then aggressive companies began to apply their engineering knowl edge to this problem. Shortly the market was flooded with lighter-steering machines. As soon as the word got around, it was no contest-all makers had to follow suit or have their products rejected by riders now accustomed to a higher level of function.

The same happened with cruisers. Fashion dictated a large steering rake that would normally make control heavy, but engineers found ways to deliver the look of sloping fork tubes with the function of a more upright (but unseen) steer axis. Lighter, more pleasant steering was the result.

Some undertakings are less forgiving. In the early days of aviation, there were many builders who were sure airplanes should resemble birds, or perhaps bats, discs or boxkites. Meanwhile, the Wright Brothers used their improvised wind tunnel to discover just what it was that made wings fly, and they built such wings and flew in their businesslike way. Others zoomed down hills in their more imaginative creations, hopped briefly into the air and crashed. Some ideas, it seemed, just didn’t fly.

Today one could perceive motorcycling as divided into two major streams. One is that of incrementally improved convention, and the other is that of wonderfully imaginative but not necessarily functional creativity. Conventional production motorcycles work very well, and they are made to work better every year by ceaseless engineering development whose results have become the main motivation to buy. It can be argued that today’s sportbikes are better than 99 percent of their riders, suggesting the question, “What is all this wonderful performance really for?” Aside from the fact that it entertains us and is actually useful to a few racers, it is a marketing tool like taller tailfins or more aggressive bumper bombs. See here, folks, our bike is better in these respects and we can prove it.

The custom-bike stream also entertains us-by its variety, its imagination, and often by its excellent craftsmanship. Alas, paralleling the fate of early aviation’s boxkites and batwings, it may collide painfully with physical reality. It has been rare for an extreme fashion statement to display a confidence-inspiring

60-mph stopping distance, or for it to nimbly traverse the orange cones of an accident-avoidance course.

Imagine a novel branch of aviation whose aim is not controlled, safe flight from point to point, but rather to somehow exemplify, even magnify, the spirit of aviation via kinetic symbolism. Very large engines, tiny wings and flexible structure are somehow pushed past the FAA to result in machines that can fly after a fashion, but in only the most limited way and not for very long. Now imagine the owners of conventional Cessna 172s, Beech Barons and Ercoupes crowding admiringly around them, murmuring, “Wow, that’s a big engine there. Mmmm, those wings are radically dinky. I sure wish I was...well, artier.”

If that were to happen, it would be much like the situation in motorcycling. Private aviation is still flying mainly designs from the 1940s. This technology works adequately, is tooled for economical production, and has been sued backward and forward until the last drop of liability has been squeezed out of it. What’s left is very conventional-even backward. Meanwhile, a steady stream of alternative airframe and engine prototypes comes and goes, but none of these makes it to the mainstream because it’s just too risky.

Today’s production motorcycle was defined by 1958, when the telescopic fork and swingarm had defeated all rivals, and the FIM, alarmed by a few side-wind instability crashes in racing, mandated today’s look of bare front wheels and no streamlining behind the rider. What had begun as a prudent emergency response to hasty 1950 aero solutions (the longtailed dustbin fairing) has since then frozen into a rigid public idea of what “looks right.” Anyone who messes with this look does so, not at risk of being sued as in aviation, but at risk of a sales sag. Styling of sport motorcycles has become very conservative, oscillating between smooth minimalism and a fascination with fiddly details like scoops, dive planes and headlight treatments.

Small wonder that innovation tends to take up residence in Chopperworld, where it’s rewarded instead of punished. Yes, it’s true that Chopperworld has its particular set of confining conventions-mile-long front ends, rollers instead of rear tires and treadmills connecting engine and gearbox-but there are two separate streams here. Imaginative show builders lead the way, often displaying serious, functional ideas in their projects. Meanwhile the copyshops push out simplified knock-offs of last spring’s hottest two-wheeled fashions.

Humans require entertainment or they become bored and troublesome. Custom builders are showing signs of restlessness, experimenting with features from outside their tradition. When too many horses graze a small pasture, the grass becomes too short for even the sharpest front teeth. The conventions in motorcycling are being overgrazed, too, and both production stylists and custom builders are looking longingly over their selfimposed fences to other places where there may yet be grass.

Can there still be design revolution? I hope so, but fear convention makes it difficult to find, or even to want, a more effective way. Is the motorcycle finished, complete? The performance of conventional bikes is currently being enhanced by sensing and control electronics, but basic problems remain. Will the motorcycle forever use only V3 of its tire tread width at a time? Will the short wheelbase necessary for quick steering forever limit maximum rates of acceleration/deceleration? Forgive me. I get like this in the winter. Go work on your bike or stare longingly at new-model brochures. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAn Immodest Proposal

June 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Blue Angel Syndrome

June 2007 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2007 By Iector Cademartori -

Roundup

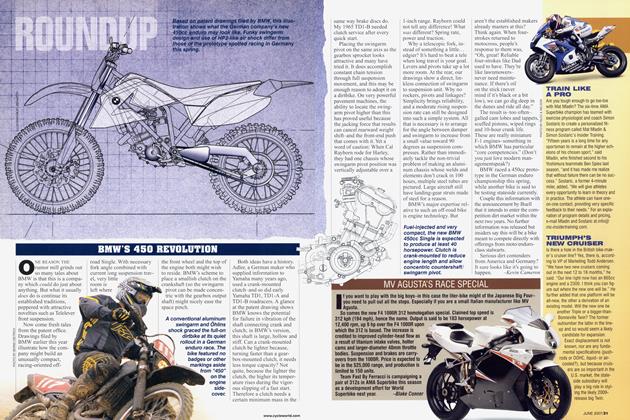

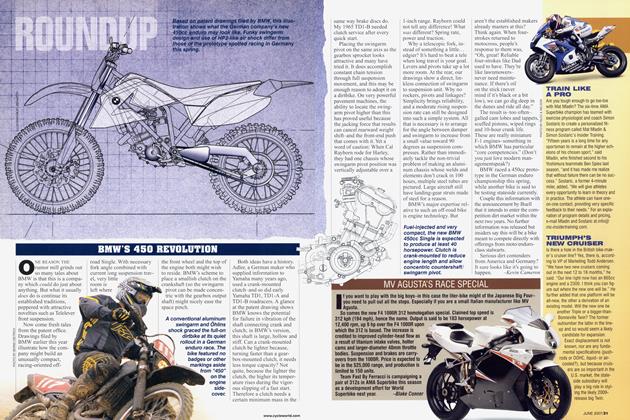

RoundupBmw's 450 Revolution

June 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMv Agusta's Race Special

June 2007 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

June 2007