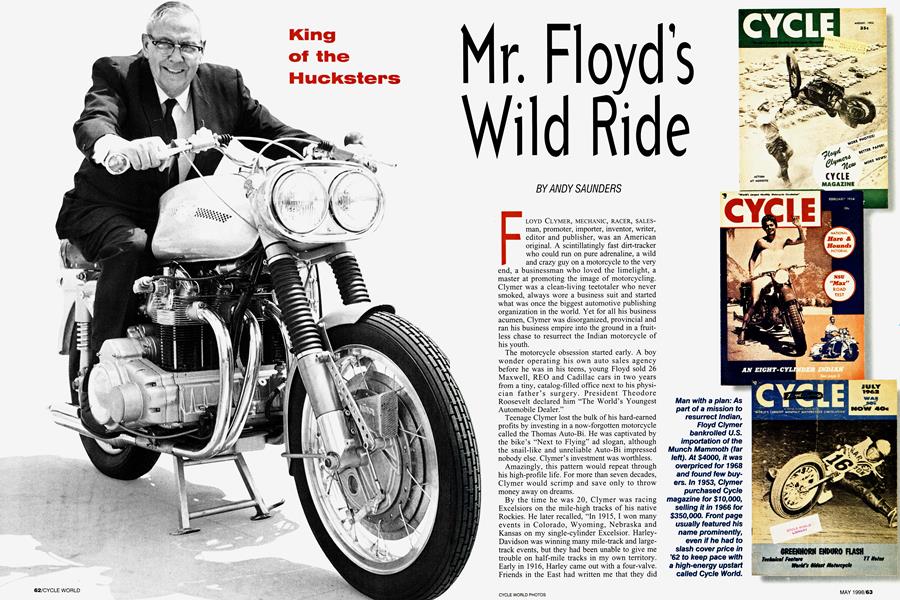

King of the Hucksters

Mr. Floyd’s Wild Ride

ANDY SAUNDERS

FLOYD CLYMER, MECHANIC, RACER, SALESman, promoter, importer, inventor, writer, editor and publisher, was an American original. A scintillatingly fast dirt-tracker who could run on pure adrenaline, a wild and crazy guy on a motorcycle to the very end, a businessman who loved the limelight, a master at promoting the image of motorcycling. Clymer was a clean-living teetotaler who never smoked, always wore a business suit and started what was once the biggest automotive publishing organization in the world. Yet for all his business acumen, Clymer was disorganized, provincial and ran his business empire into the ground in a fruitless chase to resurrect the Indian motorcycle of his youth.

The motorcycle obsession started early. A boy wonder operating his own auto sales agency before he was in his teens, young Floyd sold 26 Maxwell, REO and Cadillac cars in two years from a tiny, catalog-filled office next to his physician father’s surgery. President Theodore Roosevelt declared him “The World’s Youngest Automobile Dealer.”

Teenage Clymer lost the bulk of his hard-earned profits by investing in a now-forgotten motorcycle called the Thomas Auto-Bi. He was captivated by the bike’s “Next to Flying” ad slogan, although the snail-like and unreliable Auto-Bi impressed nobody else. Clymer’s investment was worthless.

Amazingly, this pattern would repeat through his high-profile life. For more than seven decades, Clymer would scrimp and save only to throw money away on dreams.

By the time he was 20, Clymer was racing Excelsiors on the mile-high tracks of his native Rockies. He later recalled, “In 1915, I won many events in Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska and Kansas on my single-cylinder Excelsior. HarleyDavidson was winning many mile-track and largetrack events, but they had been unable to give me trouble on half-mile tracks in my own territory. Early in 1916, Harley came out with a four-valve. Friends in the East had written me that they did

not run well in the dirt-in other words, they slowed if you could throw enough dirt at them. At the time trials, I changed to a lower gear ratio to give me a faster getaway. And it worked! I showered the four-valve in the first 3mile event, and the dirt from the wheels of my good old ‘X’ gave it dyspepsia for the rest of the day. The fourvalve magic had gone up in smoke!”

Noticing his skill and cunning, Harley-Davidson telegraphed for Clymer to enter the 1916 Dodge City 300-mile race as replacement for injured star rider Otto Walker. In 110degree heat, on an unfamiliar, ill-handling machine that “packed a lot of dynamite” into its 61 cubic inches, Clymer set fastest lap in practice, and in the race led Harley factory rider Irving Janke around the dusty horse track, both riders mounted on the potent four-valve Twins. After setting two new world records-83 miles in the first hour, 100 miles in 71 minutesClymer blew a tire at nearly 100 mph, headed into the pits, then got back on track and blazed into the lead again, until a broken valve sidelined him at the 218th mile, missing an S800 winner’s purse.

Deciding to retire from racing “before I broke all the bones in my body,” Clymer transferred his energy and adrenaline from racing to the business of motorcycling. He developed his own chain of motorcycle dealerships and a mail-order business-only to run afoul of the law and be convicted for mail fraud. He then moved West to start over again. In Los Angeles, selling Indians, he made waves. Rich Budelier, Harley-Davidson’s distributor, said to a colleague, “My fervent evening prayer is, ‘Dear Lord, what have I done so dastardly that you have seen fit to put Floyd Clymer in L.A. as my competitor?’ ”

Always one to make a splash, Clymer printed a huge catalog of motorcycle accessories in 1937. Clark Gable rode an Indian Scout on the cover. Pages of stories told of motorcycling’s champions, and every accessory Clymer had in stock was

pictured inside-few of which sold. But the books flew off the shelves on the strength of the filler stories. In 1938, Clymer sold his Indian distributorship to concentrate on the publishing business.

Following World War II, Clymer owned Automotive News magazine and “tested” new cars for Popular Mechanics, a fantastically popular magazine in the gadget-obsessed 1950s. With his talent for self-promotion, his name was often on the cover: “Floyd Clymer tests new 1954 models,” for example, with a small, blurry action picture obviously taken in a Los Angeles back lot, but accompanied by a story about wild, thousand-mile rides through the Western deserts. Colleague Don Brown, now a respected industry analyst, remembers, “One time he had this car he hadn’t driven anywhere, and when the deadline came for his article, he wrote it anyway-even though he hadn’t tested the car at all. He wrote a story on how he was putting the car through its paces through New Mexico. It was a terrific article. Until some little old lady who lived in one of those little towns, and happened to be an automobile enthusiast, read the article and wrote a letter to PM, saying on the days and times that Mr. Clymer claims to have tested this car, it was pouring with rain, and the areas he was talking about doing these high-speed runs were under water.”

Clymer went on to become publisher of Cycle, trumpeting the August, 1953, cover with, “Floyd Clymer’s New Cycle Magazine: More Photos! Better Paper! More News!” More newsletter than magazine, Cycle's circulation was a paltry 30,000 copies, and decades before desktop publishing, Clymer became a consummate multi-media artist. Hating to pay for freelance contributions, he’d clip an article or a photo from another magazine, reprinting it without even changing the typeface. “Once he lifted a half-page press release straight from the pages of Motorcyclist," recalls Bill Bagnall, that magazine’s publisher at the time. “I looked at Cycle and saw the same press release we’d carried the month before-nothing odd in that, back then both Cycle and Motorcyclist often published press releases verbatim-except this was exactly the same typeface as Motorcyclist. I called Floyd up and said, ‘Did you take the story straight out of our pages?’ Says Floyd, ‘Well, we were in a hurry.’ Oh, he was a master with a gluepot.”

And a bottom line, apparently. Former Cycle staffer Jim Davis remembers, “Floyd used to travel on the cheap everywhere. Anything-freebies, leftovers at hotels and airports-he would stuff in his outside jacket pocket. I watched him stuff half a grapefruit in there with half a submarine sandwich.

He had two bananas he picked up on an airplane, and he slept on them and they goobered through his jacket. The man was different.”

Clymer was not happy when Cycle World burst onto the scene in 1962; in fact, he tried his best to kill it. CW founder Joe Parkhurst remembers, “Floyd kept telling everyone that the industry didn’t need another magazine.

He organized a boycott against us. He convinced Triumph and BSA, and even Harley for a while, not to advertise in Cycle World. The only ones to ignore him at the time were the Berliner brothers, Mike and Joe, who imported Norton, Matchless and Ducati. Floyd’s boycott was finally broken by Don Brown over at Johnson Motors (Triumph’s West Coast distributor), who had been the editor of Cycle a few years before. He gave us some Triumph advertising, so we survived the boycott.”

Lucille Flanders, widow of handlebar king Earl Flanders, remembers, “Floyd was always smiling, even when he was stabbing you in the back.”

Parkhurst picks up the story: “Floyd sold Cycle in ’66, just five years later,

for $350,000. I’d run into him from time to time, and he said, ‘Well, now we can be friends, can’t we?’ And he gave me one of those laughs that I can only describe as heh-heh-heh-heh. Actually, I was sorry he was gone, because he was so good to compete with. He was so easy to beat!”

Clymer’s last great crusade was trying to resurrect the Indian motorcycle. Journalist Paul M. Brokaw, writing in 1970, said, “There was a passion in his heart for the old Wigwam. He made a serious effort to purchase the defunct concern, in hopes of keeping the famous marque alive. Many felt it was merely an effort to put himself in the limelight; that he had neither the finances nor the capabilities to swing such a deal. Personally, I feel he was entirely sincere in his intentions.”

In any case, Clymer appropriated the Indian name and slapped it on the sidepanels of the Sport Scout 750, an incongruous blending of cafe-racer bodywork and 1930s Indian flathead V-Twin that consumed many thousands of his dollars. The project started out as a collaboration with Friedel Munch, who needed financial backing to produce his huge, NSU car-engined Munch Mammoth. Clymer agreed to finance production, and enlisted Munch as designer of the resurrected Sport Scout. “We’ll produce 300 units by spring of 1968,” Clymer claimed to a Los Angeles Herald Examiner business reporter. “No expense has been spared to make the equipment for the Scout the finest obtainable. Electrics are all famous German Bosch...transmission gears by the firm that makes them for Mercedes, clutch made by the firm that builds Porsche racing clutches...no better quality exists anywhere.” In fact, the Scout resembled an

underpowered Munch Mammoth and had little, if any, chance of commercial success. The partnership fizzled.

Despite the breakdown of his business relationship with Munch, Clymer kept on plugging to produce and sell bikes with the Indian nameplate. Velocette was approached with the idea of doubling up its 499cc, highcamshaft Single on modified crankcases to make a lOOOcc V-Twin. First, though, the company agreed to supply a batch of Singles. Royal Enfield chipped in with 750cc Twins (see “Clymer’s Folly,” below). The stodgyas-kidney-pie British engines were fitted for new clothes by Italjet, an Italian company known today for its minibikes. At the 1969 Indianapolis AMA roadrace (promoted by Clymer), a full line of new Indians was unveiled, featuring the Velo and Enfield hybrids plus the Boy Racer, the Papoose and the Mini Mini. “Watch for the Indians coming in seven new movies,” promised the ads

for Indian’s 1970 line.

But time was running out. Clymer’s big heart gave up pumping early in 1970, and his dreams died with him. Elis widow sold off his business assets, including rights to the Indian name-though it’s doubtful if Floyd legally held those. The British merchant bank that had financed the Velo/Enfield deal called in its markers and organized the sale of the remaining Indian relics. Today, Clymer’s name lives on in the book-publishing empire that he founded, and his indefatigable huck-

ster’s spirit persists in the various Indian re-birth schemes that his death set into motion almost 30 years ago. □