Electronic absolution

TDC

Kevin Cameron

WHEN ELECTRONIC IGNITIONS FIRST Appeared on production vehicles, we all expected to be stranded on dark roads somewhere with mystery failures we couldn’t fix. We knew we could open and clean closed-up points or reconnect loose wires, but those black boxes were sealed units with devils inside. Computers were even worse—rocket science for nerds in thick glasses with 230 IQs.

Since then, electronic fuel injection and computer engine controls have surrounded us. We all know what a chip is. Computers are here to stay and they have been pretty reliable. Despite this, some racing associations have banned electronics as unfair to the little guy. In Formula One auto racing, systems routinely available on production cars-active suspension, ABS, traction control-are banned. Teams may be required to supply all their control codes as a means of assuring that banned functions are not embedded within (ever hear of a onetime, self-erasing subroutine?).

The job of electronic policeman is not an easy one. I now hear that Detroit auto-makers are suspected of writing software that can recognize an EPA driving test. If this were true, a car chosen at random could be rolled into a test cell in Ann Arbor, and as soon as the test cycle began, its onboard computer would say, iiAha\ An EPA test! Now I will switch instantly to my stored ultralow-emissions subroutine, converting myself from a drivable and practical vehicle into a sputtering, hesitating, stalling, clean-pipe paragon.”

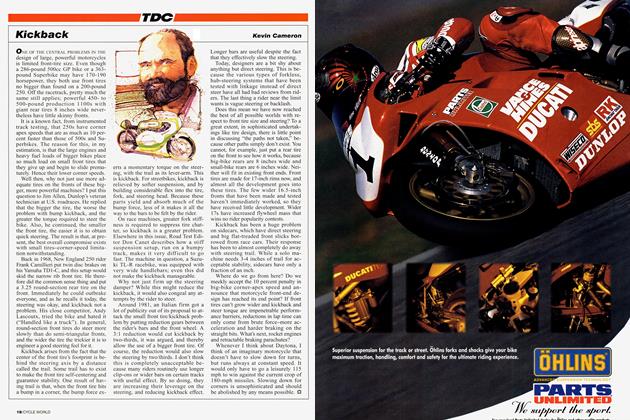

When Ducati released the fuel-injected 851, with its computer the size of a small pan of brownies, it instantly divided race tuners into two groups. One group said, “This is great. To change jetting, all I have to do is change the computer’s instructions.” The other group hated and feared the computer, and invested time in trying to replace the fuel injection with carburetors. We know which group won.

Of course, at first it wasn’t easy to talk to the Ducati’s onboard computer unless you had a friend high in the Italian government. But over time, knowledge trickled down and the usual smart-guys got on the problem. The soldering irons smoked and the keyboards rattled. Soon, the people who really cared about it could talk to their 851 computers and could burn their own chips. And it spread from there.

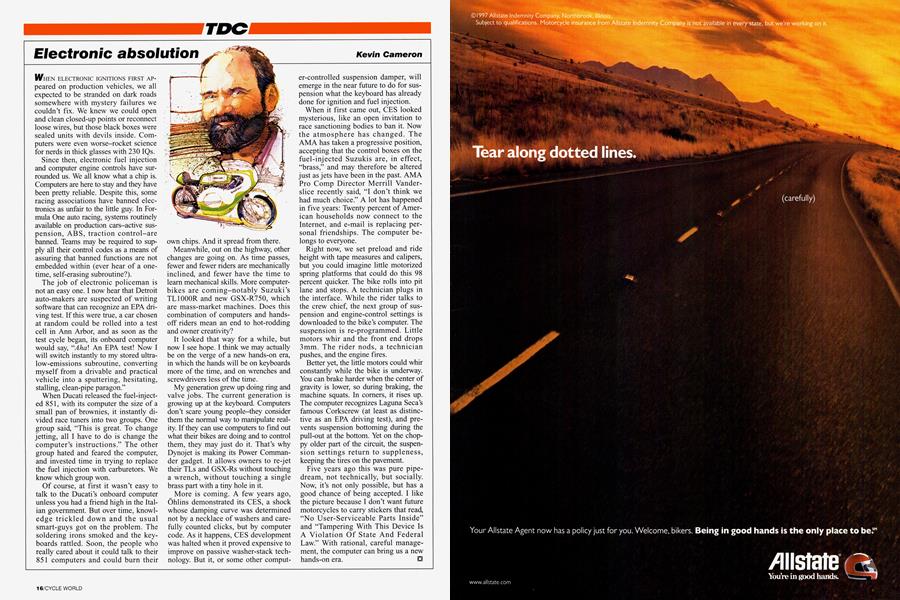

Meanwhile, out on the highway, other changes are going on. As time passes, fewer and fewer riders are mechanically inclined, and fewer have the time to learn mechanical skills. More computerbikes are coming-notably Suzuki’s TL1000R and new GSX-R750, which are mass-market machines. Does this combination of computers and handsoff riders mean an end to hot-rodding and owner creativity?

It looked that way for a while, but now I see hope. I think we may actually be on the verge of a new hands-on era, in which the hands will be on keyboards more of the time, and on wrenches and screwdrivers less of the time.

My generation grew up doing ring and valve jobs. The current generation is growing up at the keyboard. Computers don’t scare young people-they consider them the normal way to manipulate reality. If they can use computers to find out what their bikes are doing and to control them, they may just do it. That’s why Dynojet is making its Power Commander gadget. It allows owners to re-jet their TLs and GSX-Rs without touching a wrench, without touching a single brass part with a tiny hole in it.

More is coming. A few years ago, Qhlins demonstrated its CES, a shock whose damping curve was determined not by a necklace of washers and carefully counted clicks, but by computer code. As it happens, CES development was halted when it proved expensive to improve on passive washer-stack technology. But it, or some other computer-controlled suspension damper, will emerge in the near future to do for suspension what the keyboard has already done for ignition and fuel injection.

When it first came out, CES looked mysterious, like an open invitation to race sanctioning bodies to ban it. Now the atmosphere has changed. The AMA has taken a progressive position, accepting that the control boxes on the fuel-injected Suzukis are, in effect, “brass,” and may therefore be altered just as jets have been in the past. AMA Pro Comp Director Merrill Vanderslice recently said, “I don’t think we had much choice.” A lot has happened in five years: Twenty percent of American households now connect to the Internet, and e-mail is replacing personal friendships. The computer belongs to everyone.

Right now, we set preload and ride height with tape measures and calipers, but you could imagine little motorized spring platforms that could do this 98 percent quicker. The bike rolls into pit lane and stops. A technician plugs in the interface. While the rider talks to the crew chief, the next group of suspension and engine-control settings is downloaded to the bike’s computer. The suspension is re-programmed. Little motors whir and the front end drops 3mm. The rider nods, a technician pushes, and the engine fires.

Better yet, the little motors could whir constantly while the bike is underway. You can brake harder when the center of gravity is lower, so during braking, the machine squats. In comers, it rises up. The computer recognizes Laguna Seca’s famous Corkscrew (at least as distinctive as an EPA driving test), and prevents suspension bottoming during the pull-out at the bottom. Yet on the choppy older part of the circuit, the suspension settings return to suppleness, keeping the tires on the pavement.

Five years ago this was pure pipedream, not technically, but socially. Now, it’s not only possible, but has a good chance of being accepted. I like the picture because I don’t want future motorcycles to carry stickers that read, “No User-Serviceable Parts Inside” and “Tampering With This Device Is A Violation Of State And Federal Law.” With rational, careful management, the computer can bring us a new hands-on era.