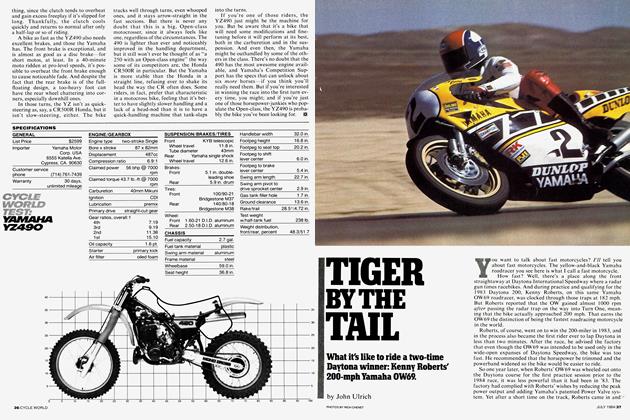

ANATOMY OF A HYBRID

A technical analysis of the OW69, a bike built for one specific purpose: to win the Daytona 200.

Kevin Cameron

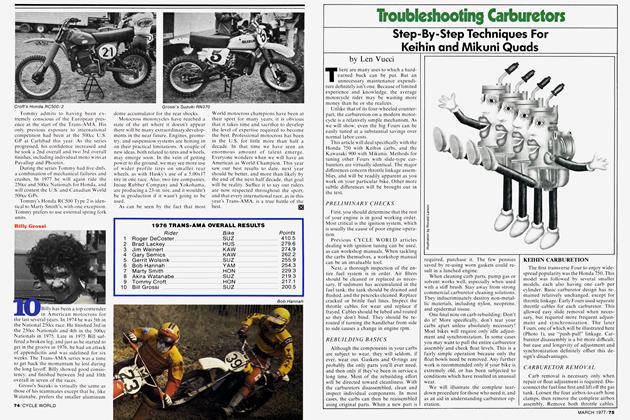

Yamaha’s OW69, the winning motorcycle at Daytona in 1983 and 1984, is a roadracing rocketship. Its brutally fast engine will spin the bike’s fat rear slick most of the way down Daytona’s long back straight to the chicane, a half-mile away. But it is also a motorcycle that is horsepower-saturated. Adding more power cannot make it go any faster.

Compare the OW69 with what you see at roadracing Nationals, and the 694.5cc Yamaha seems to be an advanced racer. It makes 150 horsepower. It has a square-Four, rotary-valve, twostroke engine. It’s built on a box-section aluminum-tube chassis. It has rising-rate, single-shock rear suspension. It is also obsolete.

How can this be, you ask? Did this bike not win Daytona the last two years? Yes, it did. But seen from the vantage point of Yamaha’s latest GP-racing technology, the OW69 is three years out of date. It’s heavy, its power curve is brutal, and it doesn’t turn all that well. Its riders, Kenny Roberts and Eddie Lawson, both regard it as too powerful to be ridden really fast, and would rather have used their 500s in the Daytona races.

All these objections are valid. But seen from the perspective of Yamaha management, the OW69 was the solution to a terrible dilemma. Prior to the ’83 Daytona event, Yamaha hadn’t been selling nearly as many motorcycles as it needed to sell. The world-wide recession had hit the company particularly hard, and arch-rival Honda was attacking on every front—including racing. Yamaha had won every Daytona 200 since 1972, and if Honda were to have broken that streak, it would have appeared that Yamaha was perhaps in deeper trouble than even the slumping sales figures indicated. The yellow-and-black therefore had to win Daytona in 1983.

Yamaha knew, of course, that Honda had developed an astoundingly fast little 500cc three-cylinder GP bike for Europe, and still had the very quick FWS1025 V-Four four-stroke that had almost upset Yamaha at Daytona in 1982. Yamaha had tried its latest 500cc OW60 in the ’82 Daytona race and it had stopped, leaving the back-up rider, Graeme Crosby, to luckily outlast the Honda attack on his old 1979 OW31 inline Four. That aging OW31 still had a potent motor, but it would have needed at least a new chassis to stand even a remote chance of winning again in 1983. Some parts were out of production and the engine had known weaknesses, thus it was not a good bet to run the steady 2:02 laps it might take to win in ’83. Yamaha’s 500cc GP bikes were felt to be too small and not designed to go 200 miles. They were fast enough, but not as stone-reliable as they would need to be. And developing something entirely new just to meet the unique needs of Daytona would break the corporate bank—and still might be unreliable.

No, the best answer was to develop a Daytona bike out of an existing design. And the choice of machinery fell to Yamaha’s interim 500, the OW60. After winning one GP in Roberts’ hands, the OW60 had become the workhorse of the Yamaha support team, racking up thousands of miles in testing and racing in 1982. Its mechanical systems were already proven and its chassis was, if not perfect, at least decent. So it was transformed into a Daytona Special called the OW69.

Don’t think, though, that the resultant motorcycle is merely a bored and stroked OW60; it’s not. Relocating the crankpins to gain a sufficiently long stroke would have made the OW60’s flywheels unacceptably weak, and there wasn’t room in the existing cases for bigger wheels. Thus, new cases and cranks had to be produced so the OW60’s 56mm x 50.6mm bore and stroke could be stretched to 64mm x 54mm dimensions. The basic engine architecture remained as before, though, with the engine cases splitting only across the plane of its four crankshafts, which is inclined forward like the four cylinders at a 45° angle. The lower crankcase and the vault-like gearcase are cast in one piece, allowing the six-speed gear cluster, with shift forks and shift drum attached, to be removed through a “door” on the engine’s right side.

The OW69’s four separate cylinders are held to the upper crankcase by long through-studs. If this engine is like recent Yamaha roadrace designs (Yamaha would not tell us everything about this engine or allow us to disassemble it), there are four separate crankshafts, paired as transverse 180° Twins, each pair sharing a single cental drive gear. Each of these two gears in turn meshes with a big gear on the jackshaft that runs across the engine behind and below the cranks. The right end of the jackshaft carries the power to the primary gears and the eight-plate clutch, while the left end drives the ÓW60-type CDI magneto. There also are cross-axis gears cut into the middle of the jackshaft to drive the waterpump and, more than likely, a gearbox lube pump. Yamaha learned way back in 1963 that there is free power to be had simply by not allowing the gears to spin in oil. The lube pump delivers an oil jet to the mesh of each pair, giving adequate lubrication without incurring any churning losses.

Each crank’s outer end carries an intake rotary valve that spins in a tight-fitting case. The discs are of thin steel and are approximately 180° cut away. As the discs turn with the cranks, they alternately open and close the ports leading from the sidemounted carburetors into each cylinder’s crankcase. This type of intake system has its drawbacks, but its potential for pure power and acceleration has been undisputed since the idea reached Japan from Germany in the middle Fifties. The beauties of rotary-valve intake are l ) when open, there are no restrictions at all between carb and crankcase, and 2) the engineer can select any opening and closing points he wants, since the timing need not be symmetrical as with piston-controlled designs.

Dinky little 34mm Mikuni Powerjet magnesium carburetors are used on the OW69, even though a 500cc racer would normally use carbs this size or larger. The reason for such small carbs is that in a two-stroke race engine of this size, even a small change in throttle opening can be too much for some cornering situtations. Response is not in strict proportion to rpm; there is always a point in the range of engine rpm or throttle opening where power rushes in, threatening to upset the bike in corners. Part of the reason why this happens is obvious: the pipes and the porting are configured to work best within a narrow rpm range. Another reason is the basic nature of carburetion, especially in high-strung racing engines. If you could look into the intake of an engine running at low rpm, you’d see that fuel streams from the needle jet in ragged blobs that push a lot of fuel through the engine unburned. As the revs rise, a point is reached at which the fuel spray suddenly changes character, becoming a fine mist that burns well and makes a lot of power.

With a rotary-valve motor like the OW69’s, this condition is exaggerated, since it has a very weak metering signal at the carburetor due to its early opening timing, which makes it even harder to get good fuel atomization at the bottom of the powerband. With reed or piston-port engines this is not such a problem, because they deliver a good suction “pop” to their carbs when the intakes open. So the OW69’s small carburetors are an attempt to make this engine carbúrete more efficiently from a lower point in the rpm range. Anyway, these 34mm Mikunis are not as much of a performance handicap as you might think; back in the days of 23mm carb restrictors in AMA racing, Kenny Roberts’ restricted 750 got through Daytona’s speed trap at 184 mph in 1980, and it was breathing through half of the intake area of this OW69.

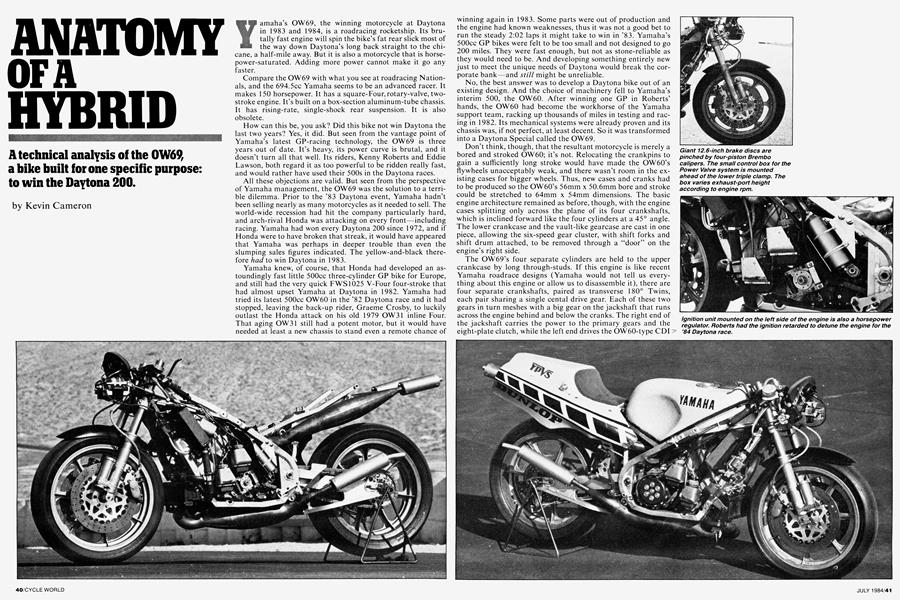

In 1983, this bike didn’t have Power Valve cylinders, and it was a beast to ride. According to Eddie Lawson, it was almost impossible to get on the throttle before the apex of Turn Two at Daytona without the risk of spinning out. The ’84 version of the OW69 does utilize the Power Valve devices. Its cylinders are cast to incorporate movable flat gates slightly downstream of each exhaust port. These gates are winched up and down by a battery-powered gear-motor acting on instructions from a small computer bolted on the front fairing mount. The gates continually adjust the effective exhaust area according to the rpm at any given moment, thus smoothing out the power down low so it can be applied sooner in the corners.

As Roberts and Lawson struggled with the excessive power of the 1983 OW69, there were two even stronger engines sitting in crates in their garages at Daytona. Which is where they stayed throughout the event. A maximum-power version of the 695 would deliver close to 175 horsepower. Any takers?

Another indication that the OW69 is not a peak-power design can be seen in its pipes, which would be fatter if Yamaha wanted all of the acceleration this engine is capable of delivering. Pipe shape is classic rotary-valve, with single-taper horns leading into short center sections, then two-stage baffle cones. The two forward pipes cross one another before extending rearward, which is simply to consume length so the fattest parts of the pipes are kept forward of the wide rear tire.

If we could peer inside the cylinders (we weren’t permitted that liberty), we would almost certainly see nothing surprising; a single, moderately sized oval exhaust port opening about 81° ATDC, and either five or seven transfers to route mixture up from the crankcase about 35° later. The cylinder walls of these aluminum castings are chromium-plated where they contact the pistons—a Yamaha development of the early Sixties. Before that, iron liners were used, but as power outputs rose, piston temperatures were driven out of sight by the iron’s insulating effect. By plating a hard wear-surface directly on the aluminum, piston temperature was brought down. Yamaha has used that design ever since; and in all likelihood, single-ring cast pistons live in those chromium-plated cylinders. Why not forgings? Alloys that can be forged become soft at two-stroke racebike operating temperatures, while unforgeable high-silicon casting alloys retain their hardness. Also, Yamaha determined, again, back in the Sixties, that a single piston ring gave the best compromise between friction loss and sealing properties.

Engine temperatures are controlled by two radiators that yield a total of 140 square inches of core area. The upper radiator is larger and sits behind the front frame tubes, above the front cylinder pair, permitting a very forward engine position. The smaller radiator sits just ahead of the front cylinders. Water is pumped first to the rear cylinders, flows to the fronts, then enters the radiators. As with other factory racers, there are no thermostats, and temperatures are controlled simply by taping over portions of the radiators. A temperature probe plugs into> the upper radiator’s header tank, sending to the only gauge on the stark instrument panel other than the tachometer.

Like all Yamaha factory roadracers since 1980, the OW69 has a rectangular-section aluminum-tube chassis. This type of design has puzzled many people, because although aluminum has just one-third the weight of steel, it also has only one-third the stiffness. The advantage of its use in a motorcycle frame lies in the better ratio of tube-diameter to wall-thickness that aluminum permits. To make a steel frame lighter, you either use smaller tubes or thinner tubes. Smaller tubing causes the frame to lose stiffness, while thinner tubing makes it hard to attach anything to the frame without masses of heavy gussets. But by using aluminum tubing of the same weight-per-foot and same diameter as the original steel tube, you end up with tubing having three times the wall thickness. This resists local buckling better than steel because the extra bulk of the aluminum is, in effect, “self-bracing.” Or, by using aluminum of the same wall thickness as the original steel tube, the tubing can be much larger in outside diameter and therefore far stiffer. Somewhere between those two extremes, the extra bulk of aluminum can allow a chassis that is lighter and stiffer than one made of steel.

That simply is on par with existing roadrace technology, just as the OW69’s rear suspension reflects Yamaha’s efforts to get level with current rising-rate suspension technology. Yamaha’s original Monoshock had been superior to twin-shock systems for some years largely because of the stiffness afforded by its triangulated swing arm, and the relative consistency of its damper units. But as Suzuki developed its rising-rate concept for roadracing, the Monoshock became more of a disadvantage than an advantage. Yamaha tested its own linkage-type suspension in 1981, but the riders didn’t like it. And the OW69, which is an offshoot of the OW60 first used in 1982, reflects the next level of Yamaha’s penetration into the mystery of suspension. A pushrod from the swing arm rotates a bellcrank, which compresses a single shock angled forward under the tank. Yamaha simplified its developmental problems in 1983 by giving up roadracing rear-damper work in Japan and adopting Swedishbuilt Ohlins units like the one used on the OW69. And, since everyone who delves into rising-rate suspension soon discovers that any sort of bushing in the linkage causes stiction, rollingelement bearings are used at all feasible points in the linkage.

The bike’s wheelbase is short—53.5 inches—which conforms with Yamaha practice. Short chassis seem to work best on long, fast tracks, and vice versa. This flies in the face of tradition, which for years has held that long motorcycles confer stability on fast tracks while short ones give quick steering on shorter tracks. But in fact, bikes become significantly harder to steer he faster they go because of the gyroscopic stability of the pinning wheels. A rider therefore could use a shorter chassis at high speed. And on short tracks, where, invariably, lower gearing is used, a short bike can wheelie too easily and thereby lose acceleration, so a longer wheelbase is preferred.

Also, the stiffer the chassis, the quicker the steering geometry that can be used without causing wobbling. Big street bikes tried steering-head angles in the 26° range a few years ago, then gradually reverted to angles in the 28-to-30° range to cut down on the wobbles. But now that stiff chassis construction is prevalent, the head angles are much steeper, and many racebikes have steering heads set at 22 or 23°. The OW69’s head isn’t that steep, but at 26°, it’s steeper than that of the old TZ750. Th& OW’s 40mm fork tubes are offset 28mm by replaceable eccentric inserts in the CNC-milled triple-clamps, yielding 105mm (4.1 in.) of trail. The fork itself is the “anti-chatter” roadracing unit developed by Yamaha about four years ago. It uses small accumulators on the fork sliders to apply gas-pressure to the damping oil without pressurizing the entire fork. This stops most damping-oil cavitation without making the ride harsh.

Dry, the OW69 weighs 297 pounds; and with 2.5 gallons of fuel, the weight distribution is 52 percent front, 48 percent rear, which is a bit heavier at the back end than a standard TZ750. Roberts likes it that way, though, because any more of a forward weight bias can work the front tire too hard on the way into the turns.

Morris seven-spoke mag wheels are used on the OW, 18inchers front and rear. Both Roberts and Dunlop have been skeptical about the “16-inch revolution,” but this special application is more than a question of steering quickness or stability; for Daytona’s 200-mile distance and this machine’s prodigious horsepower, the rider needs as much rear-tire acreage as he can get. The rear wheel uses a sprocket cush-drive from a Yamaha 500cc GP bike to protect the gearbox and chain. The small rear disc brake is from an earlier TZ250. The front wheel carries two 320mm iron discs on floating carriers that offer no resistance to the discs as they expand under the heat of braking. Each disc is gripped by one of the excellent Italian-built Brembo four-piston calipers, yet another example of Yamaha solving its problems in the most effective, least expensive way. The rear rim is a fiveinch (that’s right, five inch, not a three-inch-wide WM-5) unit needed to support the hidden technology of the giant Dunlop slick that makes all of this bike’s speed possible.

But make no mistake: This bike is obsolete nonetheless, evert if its record is two-for-two. We won’t see the OW69 at Daytona again, though, for in 1985 the formula will change to limit twostrokes to 500cc and four-strokes to 750cc. So we must be satisfied, those of us who have seen this bike in action, with only the memory of the angry, warbling sound of wheelspin as both Roberts and Lawson rode these rockets up onto the wall out of Turn Five. The bikes make an interesting page in Yamaha’s development notebook, however; for while they might not have been light, might not have offered the very best in cornering, and their riders don’t remember them with much fondness, they were brilliant and essential weapons for Yamaha at a crucial time. The company’s decision to use proven technology turned out to be far wiser than gambling on the unknown. 0