Early days, good days

TDC

Kevin Cameron

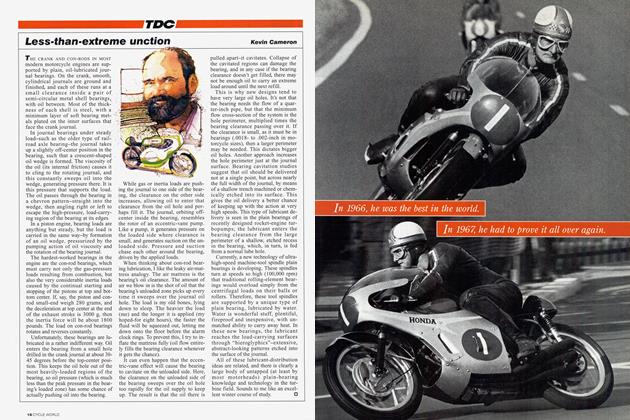

I HAVE ALWAYS LIKED BEING AT THE races, but the experience has changed over time. In 1965 I went as an open-mouthed novice, so everything was brand-new and completely intense. I knew some things about engines because I’d had an indulgent uncle who’d helped me through an overhaul or two. As you’d expect, lawnmowers and Ford Sixes revealed little about Yamaha two-strokes. Therefore, what I knew was mainly in the category of theory. Clubman veterans knew the important, real stuff like how to find the racetrack, or how to keep your bike from falling over on its trailer and then getting a hole rubbed in its gas tank by a spare tire.

Those first races answered the basic questions and established the important practicalities. I became a member of the Eyelid Hooks Club, working my job in the days, building bikes at night, and trying to get through race weekends on $80 and whatever sleep could be found in hot, vibrating trucks or between late Saturday dinners and early Sunday practices.

The intensity itself captivated me. The effort became the reason for doing it. This was like religious revelationall competing truths fell away from me. Therefore it was hard for me to enjoy things that now, in retrospect, I recall as having been especially fine moments.

Harewood Acres was a racetrack in Ontario, Canada, and was a frequent destination of mine in the 1960s. It had been a wartime flight-training airbase, and its cracked, dried-out runways had been connected with fresh asphalt to make a rough-andready race course. Gray frame barracks were the only structures. I loved going to Canada because the near presence of the bush and beyond it the Arctic always made life and the people there seem more connected with basics. At least once during my times at Harewood, practice had to be stopped to allow an airplane to make an emergency landing, as the strip was still listed for such use.

On this particular weekend, practice was only a half-day. The other half was free. I wanted to spend that time frittering with my bike, but my companions knew a restaurant on the lake where we could get fresh perch. I grumbled but went along. Setting igni-

tion timing twice wouldn’t make it any more accurate. The sun was fresh and bright, so when we were asked if we wished to eat on the dock, we filed down a steep wooden stair to tables on a floating platform. The warmth and my tiredness pushed grumpiness aside. Sunlight flickered in my eyes from the constantly moving water, and the dock itself moved slightly. I almost went to sleep there in that perfect afternoon, suspended somewhere between racing and lunch-a pretty good place to be. The food came and we ate in a state of perfect relaxation.

Another Canadian track was Ste. Jovite, in Quebec, located in the mountains. Driving in the van (no more trailers, ever!) always had the transforming quality of a night journey to a different reality, but on this particular occasion it was more. The van wound its way upward into the mountains as dawn was preparing itself in the east. Whoever was driving was the sole representative of consciousness in that truck. The rest were sleeping. In northern mountains, the winter season has a wider influence, so the fog-forming power of autumn shows itself earlier there. As the truck reached the height of land, first light illuminated what lay ahead and below-perfect white fog filling in the world like a sea, with only the peaks of the mountains visible, rising out of it as fantasy islands. The driver was so struck by this world that he stopped the truck and wakened the

rest of us to look as well. No one-not even I-objected to the delay. We had gone to sleep on the endlessly humming highway, interrupted briefly in the night glare of gas stations, driven our stints, slept again and now here we were overlooking this strange place.

We drove on, the sun rose higher and the fog became nothing. The world was back to normal. Ste. Jovite when we reached it was just another asphalt racetrack.

Years later I was at Monza, in Italy. Tape I’d put on the radiator of Rich Schlachter’s TZ250 to get operating temp had come off and gone straight in a carburetor. This zeroed out our day. For distraction, I watched the wet 500cc race come to the line. Kenny Roberts had said water-cooled tires were the only way he could win with the rubber he had. He did, leaving everyone down the straights with the uncivilized power of his new OW-54 Yamaha, holding Suzuki RG500-mounted opponents to a draw in the slippery corners. I watched the podium ceremony from the cavernous timing and scoring building. Then I saw Kenny, a huge crowd following him in characteristic Italian style, enter the building and start up its four-sided open stairwell. The people behind him were roaring and shouting, filling the building like rising water. I withdrew from their crushing approach into a doorway. As Kenny climbed past, he saw me and deliberately winked.

All serious participants fly to races now, but in the 1970s I was still driving. It was one of my special pleasures to drive through western darkness for hours, watching the gas gauge creep over toward somebody else’s turn to drive, watching the blackness beyond the lights for a town. A person can do some quiet thinking in those hours. The phone can’t ring, there are no engines to build, and everyone else is asleep. There are no distractions. I never reached any profound conclusions, but I value the time I spent in that apparently empty way-just going. Each power stroke of the cracked cast pistons in that old red van subtracted something from the gas gauge. After about three million of those tiny events, I’d see a line of white and colored lights far ahead, a town shining in the dark world. Land ho. □