The Parkhurst Papers

UP FRONT

David Edwards

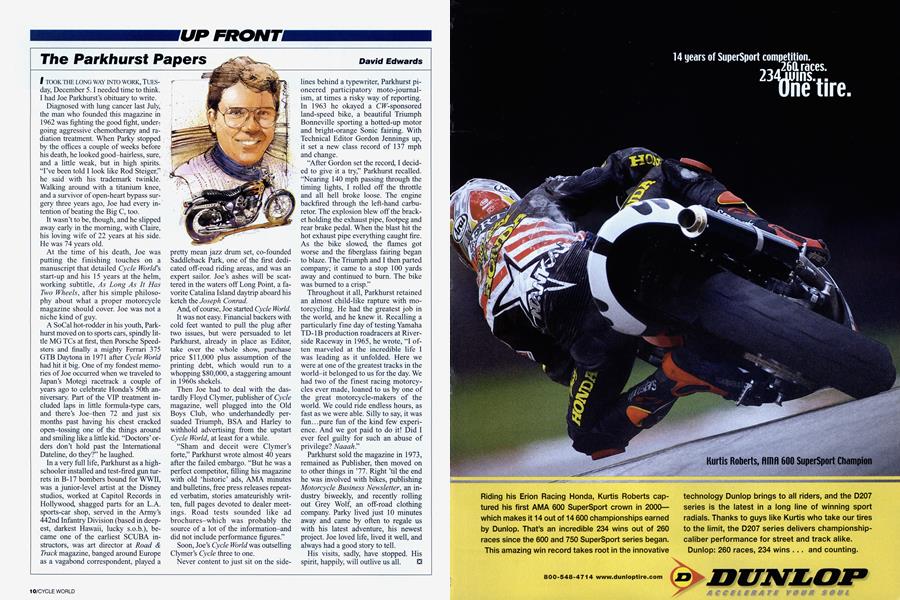

I TOOK THE LONG WAY INTO WORK, TUESday, December 5. I needed time to think. I had Joe Parkhurst’s obituary to write.

Diagnosed with lung cancer last July, the man who founded this magazine in 1962 was fighting the good fight, undergoing aggressive chemotherapy and radiation treatment. When Parky stopped by the offices a couple of weeks before his death, he looked good-hairless, sure, and a little weak, but in high spirits. “I’ve been told I look like Rod Steiger” he said with his trademark twinkle. Walking around with a titanium knee, and a survivor of open-heart bypass surgery three years ago, Joe had every intention of beating the Big C, too.

It wasn’t to be, though, and he slipped away early in the morning, with Claire, his loving wife of 22 years at his side. He was 74 years old.

At the time of his death, Joe was putting the finishing touches on a manuscript that detailed Cycle World's start-up and his 15 years at the helm, working subtitle, As Long As It Has Two Wheels, after his simple philosophy about what a proper motorcycle magazine should cover. Joe was not a niche kind of guy.

A SoCal hot-rodder in his youth, Parkhurst moved on to sports cars, spindly little MG TCs at first, then Porsche Speedsters and finally a mighty Ferrari 375 GTB Daytona in 1971 after Cycle World had hit it big. One of my fondest memories of Joe occurred when we traveled to Japan’s Motegi racetrack a couple of years ago to celebrate Honda’s 50th anniversary. Part of the VIP treatment included laps in little formula-type cars, and there’s Joe-then 72 and just six months past having his chest cracked open-tossing one of the things around and smiling like a little kid. “Doctors’ orders don’t hold past the International Dateline, do they?” he laughed.

In a very full life, Parkhurst as a highschooler installed and test-fired gun turrets in B-17 bombers bound for WWII, was a junior-level artist at the Disney studios, worked at Capitol Records in Hollywood, shagged parts for an L.A. sports-car shop, served in the Army’s 442nd Infantry Division (based in deepest, darkest Hawaii, lucky s.o.b.), became one of the earliest SCUBA instructors, was art director at Road & Track magazine, banged around Europe as a vagabond correspondent, played a pretty mean jazz drum set, co-founded Saddleback Park, one of the first dedicated off-road riding areas, and was an expert sailor. Joe’s ashes will be scattered in the waters off Long Point, a favorite Catalina Island daytrip aboard his ketch the Joseph Conrad.

And, of course, Joe started Cycle World.

It was not easy. Financial backers with cold feet wanted to pull the plug after two issues, but were persuaded to let Parkhurst, already in place as Editor, take over the whole show, purchase price $ 11,000 plus assumption of the printing debt, which would run to a whopping $80,000, a staggering amount in 1960s shekels.

Then Joe had to deal with the dastardly Floyd Clymer, publisher of Cycle magazine, well plugged into the Old Boys Club, who underhandedly persuaded Triumph, BSA and Harley to withhold advertising from the upstart Cycle World, at least for a while.

“Sham and deceit were Clymer’s forte,” Parkhurst wrote almost 40 years after the failed embargo. “But he was a perfect competitor, filling his magazine with old ‘historic’ ads, AMA minutes and bulletins, free press releases repeated verbatim, stories amateurishly written, full pages devoted to dealer meetings. Road tests sounded like ad brochures-which was probably the source of a lot of the information-and did not include performance figures.”

Soon, Joe’s Cycle World was outselling Clymer’s Cycle three to one.

Never content to just sit on the sidelines behind a typewriter, Parkhurst pioneered participatory moto-journalism, at times a risky way of reporting. In 1963 he okayed a CIT-sponsored land-speed bike, a beautiful Triumph Bonneville sporting a hotted-up motor and bright-orange Sonic fairing. With Technical Editor Gordon Jennings up, it set a new class record of 137 mph and change.

“After Gordon set the record, I decided to give it a try,” Parkhurst recalled. “Nearing 140 mph passing through the timing lights, I rolled off the throttle and all hell broke loose. The engine backfired through the left-hand carburetor. The explosion blew off the bracket holding the exhaust pipe, footpeg and rear brake pedal. When the blast hit the hot exhaust pipe everything caught fire. As the bike slowed, the flames got worse and the fiberglass fairing began to blaze. The Triumph and I then parted company; it came to a stop 100 yards away and continued to burn. The bike was burned to a crisp.”

Throughout it all, Parkhurst retained an almost child-like rapture with motorcycling. He had the greatest job in the world, and he knew it. Recalling a particularly fine day of testing Yamaha TD-1B production roadracers at Riverside Raceway in 1965, he wrote, “I often marveled at the incredible life I was leading as it unfolded. Here we were at one of the greatest tracks in the world-it belonged to us for the day. We had two of the finest racing motorcycles ever made, loaned to us by one of the great motorcycle-makers of the world. We could ride endless hours, as fast as we were able. Silly to say, it was fun...pure fun of the kind few experience. And we got paid to do it! Did I ever feel guilty for such an abuse of privilege? Naaah.”

Parkhurst sold the magazine in 1973, remained as Publisher, then moved on to other things in ’77. Right ’til the end he was involved with bikes, publishing Motorcycle Business Newsletter, an industry biweekly, and recently rolling out Grey Wolf, an off-road clothing company. Parky lived just 10 minutes away and came by often to regale us with his latest adventure, his newest project. Joe loved life, lived it well, and always had a good story to tell.

His visits, sadly, have stopped. His spirit, happily, will outlive us all. U