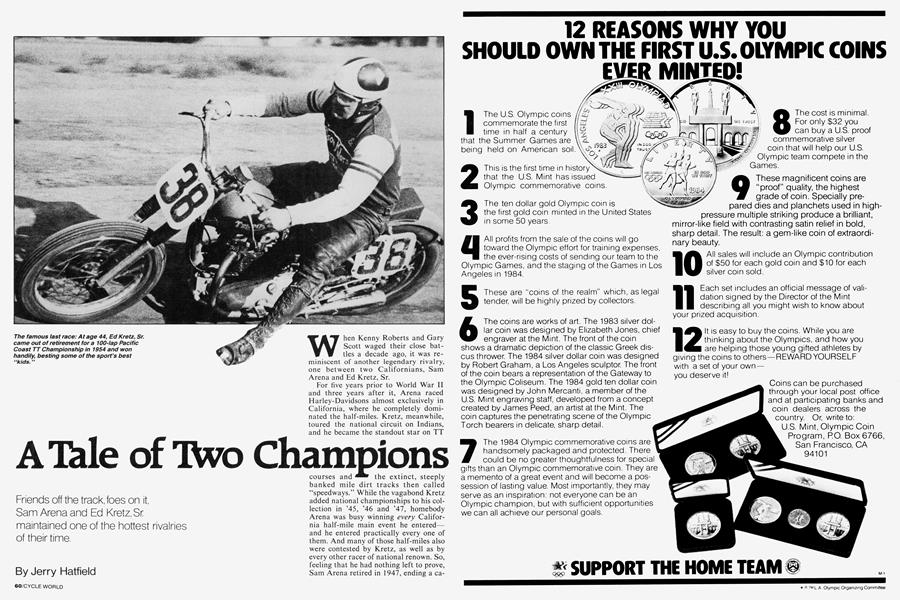

A Tale of Champions

Friends off the track, foes on it, Sam Arena and Ed Kretz, Sr. maintained one of the hottest rivalries of their time.

Jerry Hatfield

When Kenny Roberts and Gary Scott waged their close battles a decade ago, it was reminiscent of another legendary rivalry, one between two Californians, Sam Arena and Ed Kretz, Sr.

For five years prior to World War II and three years after it, Arena raced Harley-Davidsons almost exclusively in California, where he completely dominated the half-miles. Kretz, meanwhile, toured the national circuit on Indians, and he became the standout star on TT courses and the extinct, steeply banked mile dirt tracks then called “speedways.” While the vagabond Kretz added national championships to his collection in ’45, ’46 and ’47, homebody Arena was busy winning every California half-mile main event he entered— and he entered practically every one of them. And many of those half-miles also were contested by Kretz, as well as by every other racer of national renown. So, feeling that he had nothing left to prove, Sam Arena retired in 1947, ending a career that few could ever hope to match.

So, too, did that mark the end of a special rivalry. Racing was a two-brand game back then between Harley-Davidson and Indian, and brand-loyalty—between fans and racers alike—often was taken much too seriously. But not between Arena and Kretz, who were mutual fans as well as intense rivals. Once, in fact, Kretz had helped Arena and his sponsor/builder/tuner Tom Sifton get their Harley ready for the Oakland Mile, figuring that any race without Sam Arena wouldn’t be much of a race at all. Kretz even agreed to help verify the performance of Arena’s machine by running his Indian against Arena’s H-D in a lastminute practice session, thus robbing his own race bike of some of its muchneeded reliability—a commodity that was even more precious in those days than it is today. “It was the acme of sportsmanship,” said Sifton as he recalled that memorable incident.“If you could beat Ed Kretz,” he added wistfully but with the utmost respect, “you could beat anybody.”

After his retirement, Arena worked in Sifton’s Harley-Davidson dealership during the early Fifties, where he followed with great interest the fortunes of Sifton's latest star, be it Kenny Eggers or National Number One Larry Headrick —or, in particular, the kid called “Moke,” Joe Leonard. And possessing a dry sense of humor and a deadpan delivery, Arena seldom missed an opportunity to make his favorite target, Leonard, the object of his mock scorn. Like the time that Leonard arrived at the Harley shop and proudly announced that he had broken the record for a 50-mile main event by several seconds. Unimpressed, Arena took Leonard by the arm and led him to the back of the shop. Pointing to the roof, Arena called Leonard’s attention to the large poster affixed to the rafters. “Read it, Moke,” said Arena matter-of-factly.

Leonard quietly began to mutter the words on the poster. “Harley-Davidson wins 1938 200-mile Oakland Speed Classic. Sam Arena, on 45WLDR Harley-Davidson, smashes old record by 19 minutes, 20.6 seconds 19 minutes!"

“Now, Moke,” Arena calmly replied, “when you've broken a record by 19 minutes, come back and brag about it. Maybe I’ll be interested.” Leonard never succeeded in doing that, but he did manage to set quite a few records of his own. In 1954, in fact, the story of the racing season had two elements: the uncanny riding ability of Joe Leonard, and the engine-building wizardry of his tuner, Tom Sifton. Having just sold his Harley dealership to Arena, Sifton was able to devote all of his attention to racing. And at the request of H-D mogul Walter Davidson, Jr., Sifton effected a dramatic horsepower increase in the bike that Leonard campaigned in 1954, in the process laying the foundation for Harley-Davidson’s dominance of American racing for the next 15 years. During that season, Leonard captured the Number One plate by bagging an incredible eight nationals, winning in mile, half-mile, TT and roadracing competition, which was every type of national event on the calendar at the time. No rider since has won more than six nationals in one season, despite the fact that the schedule now, as it has for quite a while, includes about twice the number of events as in 1954.

No one understood or appreciated Leonard’s meteoric rise to the top as well as Sifton did. “When Joe came around in '51 looking for a ride,” Sifton recalls, “he was just an Amateur (the equivalent of today’s Junior classification). He won all the Amateur miles, every one of them. And on a half-mile in ’52 he beat my top rider, Kenny Eggers.”

Leonard progressed steadily from that point, which wasn’t all that easy for a man who was considerably bigger than most of his top competitors. At that time, being able to pare about seven pounds off of a racing bike was the equivalent of finding one more horsepower in the engine. And that power-to-weight relationship was all-important on the mile tracks, where speed, more than handling, usually was the deciding factor. So the 180-pound Leonard was handicapped for performance on the straightaway. “But Joe used a longer straightaway than anyone else,” remembers Sifton. “He could drive into a corner 30, 40, 50 feet farther than the other riders. He made up for his weight disadvantage. And that was his forte.”

Meanwhile, 1954 was a very different kind of year for Ed Kretz. He had been retired from racing for nearly two years, and his involvement in the sport was limited to pitting for his son, Ed Kretz, Jr. But one day, while sitting in the quietude of his Triumph dealership in Monterey

Park, California, Ed, Sr. looked up from his paperwork and contemplated his personal street machine, a 650cc Triumph. The bike epitomized the “bobber” look popular then, with abbreviated fenders and a two-gallon fuel tank lifted from the California-built Mustang lightweight. Kretz began to wonder how it might feel to have one more go at it, one more fling at age 44. Soon the silence was broken by the clatter of wrenches as Kretz hurriedly removed lights, mufflers and all other bits of street paraphernalia. There was a TT race about to begin just a few> miles away, and Kretz figured that if he really hustled, he could get there in time to try to qualify.

At the exact same time, Joe Leonard, sporting his new Number One plate, was just finishing his practice laps on that very same track. His plan was to pick up some easy money by winning the race while also strutting his stuff as the new Number One.

A few moments later, Kretz arrived without a moment to spare. The other riders all had qualified, so Kretz immediately topped off his two-gallon Mustang tank and was on his way. Quickly, he qualified, and just as quickly, the race was underway.

All sorts of thoughts passed through Kretz’s mind as the race progressed. He wondered how he was doing, since he had no fancy, organized pit crew to signal him. Where was Leonard, the new Number One? Was there enough gas in his tiny tank to finish? That last thought was unsettling, so Kretz unscrewed the cap and peeked inside, all the while blasting full-bore around the track onehanded. Just about everyone in the stands and in the pits saw that move and concluded that Kretz was running out of gas, so many onlookers moved their gas cans near trackside, ready to give aid if needed. It might have been an era in which hard feelings between Harley and British-bike lovers were all too frequent, but not where Ed Kretz was concerned. The would-be helpers, many of whom were wearing Harley-Davidson shirts, all knew that they couldn’t legally help the Triumph-mounted Kretz, but they were prepared to try, anyway.

Kretz’s fears were unjustified. He needed no gas, and crossed the finish line the victor in this, his last race. And in the meantime, Joe “Moke” Leonard was still motoring mightily to go the full distance. The new Number One, a young man still in his twenties, had been lapped by the 44-year-old Kretz. But in that respect, at least, Leonard had plenty of company.

A couple of days later, Leonard stopped by his home base, Sam Arena’s Harley shop in San Jose, California. Word of the TT had already reached Arena, but he feigned ignorance of the outcome. “How’d the race go, Moke?”

“Well,” Leonard said rather sheepishly, “Kretz won it.”

“Kretz Junior or Kretz Senior,” queried Arena, rubbing it in while struggling to contain his laughter.

“Senior,” said Leonard.

Arena, veteran of countless battles with Ed Kretz, Sr., savored the moment. “Look, Moke,” he admonished, “you go down there and let Kretz beat you, and he’s an old man! What if you had to race him like I did—when he was 25 years old?”

What if, indeed. M