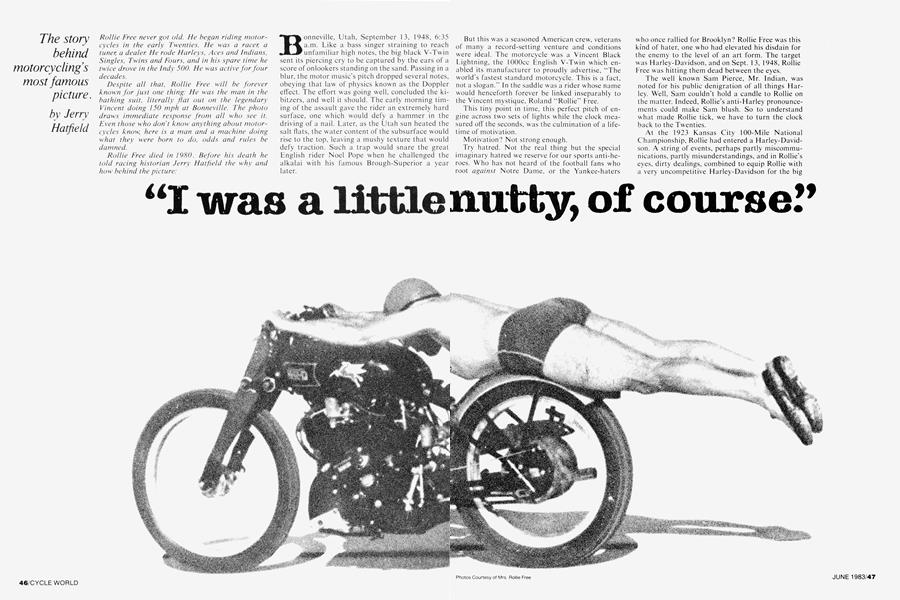

“I was a little nutty, of course."

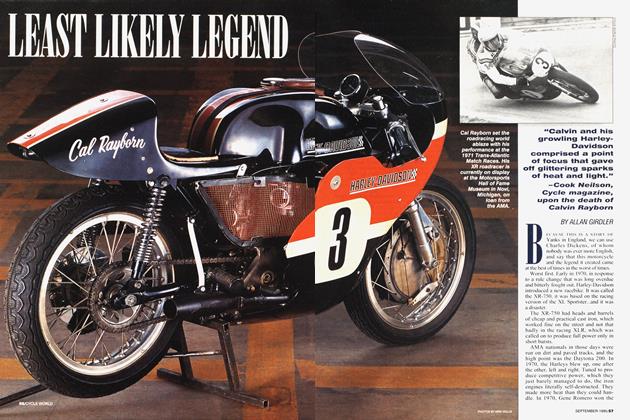

The story behind motorcycling’s most famous picture.

Jerry Hatfield

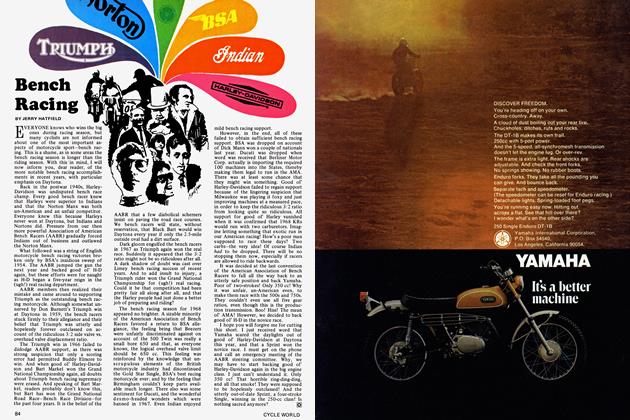

Rollie Free never got old. He began riding motorcycles in the early Twenties. He was a racer, a tuner, a dealer. He rode Harleys, Aces and Indians, Singles, Twins and Fours, and in his spare time he twice drove in the Indy 500. He was active for four decades.

Despite all that, Rollie Free will be forever known for just one thing: He was the man in the bathing suit, literally fiat out on the legendary Vincent doing 150 mph at Bonneville. The photo draws immediate response from all who see it. Even those who don't know anything about motorcycles know, here is a man and a machine doing what they were born to do, odds and rules be damned.

Rollie Free died in 1980. Before his death he told racing historian Jerry Hatfield the why and how behind the picture:

Bonneville, a.m. Like Utah, a bass September singer straining 13, 1948, to reach 6:35 unfamiliar high notes, the big black V-Twin sent its piercing cry to be captured by the ears of a score of onlookers standing on the sand. Passing in a blur, the motor music's pitch dropped several notes, obeying that law of physics known as the Doppler effect. The effort was going well, concluded the kibitzers, and well it should. The early morning timing of the assault gave the rider an extremely hard surface, one which would defy a hammer in the driving of a nail. Later, as the Utah sun heated the salt flats, the water content of the subsurface would rise to the top, leaving a mushy texture that would defy traction. Such a trap would snare the great English rider Noel Pope when he challenged the alkalai with his famous Brough-Superior a year later.

But this was a seasoned American crew, veterans of many a record-setting venture and conditions were ideal. The motorcycle was a Vincent Black Lightning, the lOOOcc English V-Twin which enabled its manufacturer to proudly advertise, “The world’s fastest standard motorcycle. This is a fact, not a slogan.” In the saddle was a rider whose name would henceforth forever be linked inseparably to the Vincent mystique, Roland “Rollie” Free.

This tiny point in time, this perfect pitch of engine across two sets of lights while the clock measured off the seconds, was the culmination of a lifetime of motivation.

Motivation? Not strong enough.

Try hatred. Not the real thing but the special imaginary hatred we reserve for our sports anti-heroes. Who has not heard of the football fans who root against Notre Dame, or the Yankee-haters who once rallied for Brooklyn? Rollie Free was this kind of hater, one who had elevated his disdain for the enemy to the level of an art form. The target was Harley-Davidson, and on Sept. 13, 1948, Rollie Free was hitting them dead between the eyes.

The well known Sam Pierce, Mr. Indian, was noted for his public denigration of all things Harley. Well, Sam couldn’t hold a candle to Rollie on the matter. Indeed, Rollie’s anti-Harley pronouncements could make Sam blush. So to understand what made Rollie tick, we have to turn the clock back to the Twenties.

At the 1923 Kansas City 100-Mile National Championship, Rollie had entered a Harley-Davidson. A string of events, perhaps partly miscommunications, partly misunderstandings, and in Rollie’s eyes, dirty dealings, combined to equip Rollie with a very uncompetitive Harley-Davidson for the big board track event. The cherry on the sundae was the aftermath of the race, when the Kansas City Harley-Davidson dealer laid claim to Rollie's special wheels, which had either been bought or rented, depending on who was doing the talking.

“I dedicated my life to gettin' even with HarleyDavidson. I went down to AÍ Crocker, the Indian dealer, and said I'd like to have a job selling Indian motorcycles. I told him why; I wanted to get even with Milwaukee. And I said, ‘Look, I'll work 24 hours a day. You give me a fast Indian and I'll fix your town for you.' ”

So Crocker hired Free, and Rollie kept his end of the bargain. The first order of business was establishing rapport with the Kansas City Harley contingent.

“I'd go down by the Harley shop at night when they’re all out front, drinkin’ beer out of The Growler the can across the road. They used to crowd Indian guys into the curbing. When they'd go by, the Harley guys would jump on bikes, run up, and crowd ’em into the curbing. Oh, they were rough! I went down and I was a little nutty, of course and I said, ‘Look, I'm going to ride up and down by here, and if any of you fellas want to do any crowding, come on out. When you pick yourselves up, I’ll still be going up and down, ’cause I’ll kick front wheels with you until it doesn't work.’ ”

“They didn’t get off the curbing. I went by ’em. I ended up with three or four Chiefs ( 1 200cc sidevalve V-Twins). And we'd all go by—pop the pipes at ’em, hit the kill button and load 'em, and let go and bang ’em, and nobody got off the curbing nobody. I mean, they thought I was insane, which I was.”

Rollie had a knack for making slow motorcycles go fast. After a tour with the Indian company as a traveling field man, he took on the Indianapolis Indian agency in the late Twenties and honed his tuning skills to a fine edge.

“For 15 years I never lost a quarter. I offered anybody I’d bet anybody that’d come in my door. I'd say, ‘Well, there’s three of ’em sittin' there. Which way do you want?’ I had a Scout (750cc side-valve), a Chief, and a four cylinder (1300cc) that I’d play with. And I’d say, ‘You got a hundred bucks, jughead?’ They would run for the Harley place down there and tell 'em what that so-and-so said up there. But they didn’t come down.”

Rollie became particularly skilled at souping up the 750cc side-valve Indian Sport Scout, so much so that his “laying on of the hands” produced Sport Scouts that regularly trimmed the Harley-Davidson lOOOcc overhead-valve jobs, the sixty-ones.

“The sixty-ones weren't fast when they came out; they'd only do about 93 or 94 miles an hour. A real good one would run a hundred and one or two. Hell, the Scouts would run a hundred and ten or twelve miles an hour. I had no trouble.”

In 1937, at a Louisville, Kentucky race meet, Rollie had a confrontation with TT star and Harley dealer J.B. Jones. At issue was whether or not Jones had been using an oversized, stroked, Harley during the day’s events. To understand part of the conversation, you need to know that, at the time, the AMA Class C record for 750cc (45 cubic inch) side-valves was 102.048 mph, by Joe Petrali, at Daytona Beach, on a Harley-Davidson. When the two stood face to face in the pits, Jones said, “I understand you thought my motorcycle was stroked.”

Free replied, “I didn’t say that. I said that whenever a Harley went by an Indian it was either oversized or the Indian was sick. Look, I came down here on an Indian Scout, named Papoose, with my wife on back. I can beat the Harley beach record with my wife on back of the machine double.”

“And he’s gettin' mad; and I want him mad, ’cause that’s the only way you can get ’em to bet. I said, ‘I got 300 bucks anytime.' He says, ‘Well, I’d like to run a match race.’ I says, ‘You got it, buddy. Let’s see the money.’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘it’s a gentlemen’s bet.’ I says, 7 never had a gentlemen s bet with a Harley guy in my life. I want the money up.' ”

They raced, and of course, Free trimmed Jones by a wide margin. Rollie even offered to run his 750cc Scout against Jones’ hopped up 1 300cc Harley Eighty, but the Harley man wisely declined. The essence of Free’s tuning was in what we now sometimes refer to as blueprinting an engine. Rollie would completely disassemble an engine, and then painstakingly put it back together. Torquing was done in increments of one foot-pound in a regular pattern until all bolts, nuts, and studs were stressed exactly the right amount. As a result, cylinder bores were more nearly true. Free also was adept at porting and was among the first to recognize the importance of eliminating turbulence throughout the exhaust system by careful mating of headers and ports.

Rollie put his money where his mouth was in March of 1938, when he took a Chief and a Scout to Daytona Beach to attack Petrali’s records. Free was unable to top the Harley-Davidson lOOOcc record of 136.183 mph, but he blew the 750cc record to hell and back. When he left home, he told his wife, “If I don’t beat ’em by 10 miles an hour, I won't even come home.” Alas, Rollie broke the 750cc record by “only” 9.5 mph, hitting 1 1 1.55 mph, but he did return home. The problem was a 17 mph crosswind. The beach was also rough.

“The beach was lousy. See, Harley waited for six days, or I don’t remember if it was six days or six weeks for a perfect beach down there. When I ran it, the beach was so rough the fuel would come out and come back on again. I'm talking ’bout a real rough beach. But hell, the Scout ran so good I wasn't worried about gettin' a record. I could beat a hundred and two-oh-four-eight with my wife on back.”

Rollie became a member of the AMA competition committee, and had the audacity to publicly accuse certain Harley-Davidson supporters of unfair officiating. And right in the presence of Walter Davidson! Free won on the issue at hand, with Davidson’s support, and achieved a rule change which required a neutral starter at national championships. But Rollie’s term was not renewed, for he was, in his own words, “stormy petrel.”

As well as his ordinary tuning know-how, Rollie Free had mastered the art of tuning while riding. In a riding career dating back to youthful jaunts on a four cylinder Ace, Rollie had learned to use his index finger to vary the effective size of a carburetor venturi.

So we return to September 1 3, 1948. With a wellnurtured lifelong grudge, an uncanny knack at extracting maximum performance from engines, and self confidence bolstered by countless hours of feetout-back riding, Rollie Free finally put to rest Joe Petrali's American motorcycle record of 136.183 mph. Rollie and the Vincent motored to a two-way average of 150.31 mph.

The actual run, as mentioned, was simply a welltuned engine working with perfect conditions.

Of course there was more to it than that. The technique, literally flat on the tank with legs outstretched, was routine, in record speed circles at least. The lack of costume was simply because on an earlier try Free had fallen fractionally short of the magic 150, so he stripped off his leathers and ran in bathing suit and borrowed tennis shoes. He later quipped that if he'd been able to borrow smaller sneakers they wouldn’t have flapped and he’d have clocked 151. Another account quotes him as saying he didn't wear a helmet but because it was so cold on the flats at dawn, his head turned blue and nobody noticed.

That was a joke. Even so, when the sanctioning club later saw the pictures they were properly horrified and the rules for full coverage now are strictly enforced. You will not, as they say, see a record run like Free’s ever again.

The record was more than a record. Mostly the effort was for the fun of it. The bike’s owner, sportsman John Edgar, enjoyed challenge as much as Free did. The factory wasn’t really involved, nor did they suspect that the magic 150 and the power of the name Black Lightning would permanently fix Vincent as the fastest motorcycle on earth, never mind that a stock Black Shadow' would do 1 25 mph despite a speedometer that read to 150.

What Rollie Free’s ride was not, was a publicity stunt. But it came at a time when English bikes were just beginning to arrive on these shores and no doubt the forces at Harley were willing to belittle the quality of the invaders. Thus the Vincent records reflected well on the entire British industry, so much so that a British trade official wrote Rollie a letter, saying, “This enabled us to sell more motorcycles. All England thanks you.”

Rollie Free, the man who’d dedicated his life to revenge against Harley-Davidson, had finally gotten even.