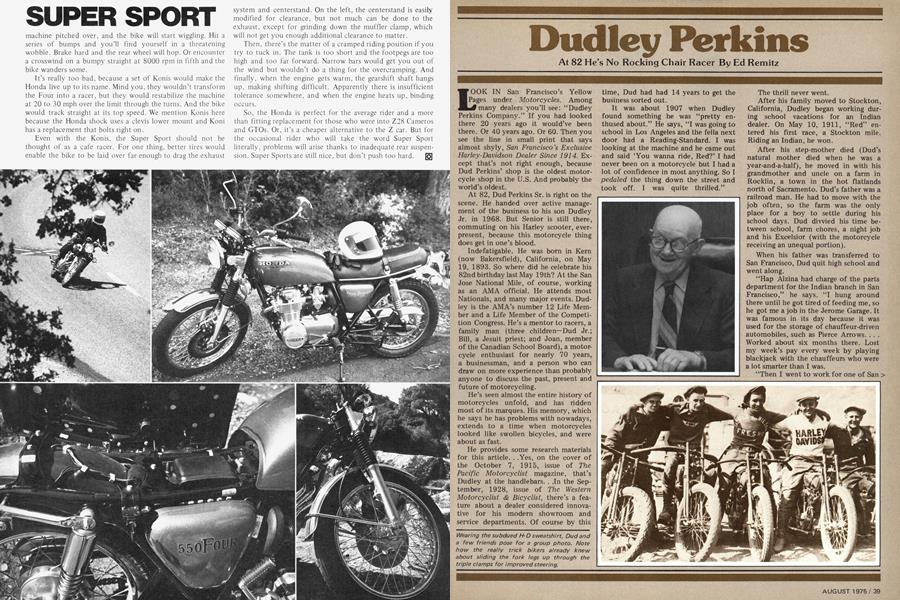

Dudley Perkins

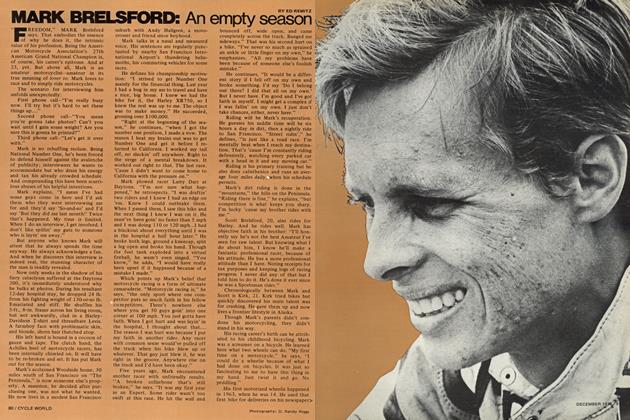

At 82 He's No Rocking Chair Racer By Ed Remitz

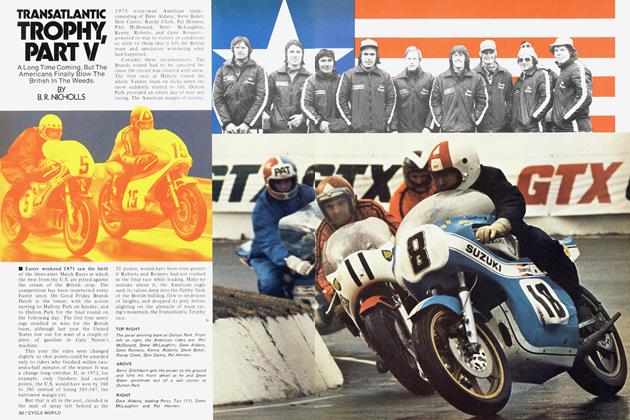

LOOK IN San Francisco’s Yellow Pages under Motorcycles. Among many dealers you’ll see: “Dudley Perkins Company.” If you had looked there 20 years ago it would’ve been there. Or 40 years ago. Or 60. Then you see the line in small print that says almost shyly, San Francisco's Exclusive Harley-Davidson Dealer Since 1914. Except that’s not right enough, because Dud Perkins’ shop is the oldest motorcycle shop in the U.S. And probably the world’s oldest.

At 82, Dud Perkins Sr. is right on the scene. He handed over active management of the business to his son Dudley Jr. in 1968. But Senior is still there, commuting on his Harley scooter, everpresent, because this motorcycle thing does get in one’s blood.

Indefatigable. He was born in Kern (now Bakersfield), California, on May 19, 1893. So where did he celebrate his 82nd birthday last May 19th? At the San Jose National Mile, of course, working as an AMA official. He attends most Nationals, and many major events. Dudley is the AMA’s number 12 Life Member and a Life Member of the Competition Congress. He’s a mentor to racers, a family man (three children—Dud Jr.; Bill, a Jesuit priest; and Joan, member of the Canadian School Board), a motorcycle enthusiast for nearly 70 years, a businessman, and a person who can draw on more experience than probably anyone to discuss the past, present and future of motorcycling.

He’s seen almost the entire history of motorcycles unfold, and has ridden most of its marques. His memory, which he says he has problems with nowadays, extends to a time when motorcycles looked like swollen bicycles, and were about as fast.

He provides some research materials for this article. . .Yes, on the cover of the October 7, 1915, issue of The Pacific Motorcyclist magazine, that’s Dudley at the handlebars. . .In the September, 1928, issue of The Western Motorcyclist & Bicyclist, there’s a feature about a dealer considered innovative for his modern showroom and service departments. Of course by this time, Dud had had 14 years to get the business sorted out.

It was about 1907 when Dudley found something he was “pretty enthused about.” He says, “I was going to school in Los Angeles and the fella next door had a Reading-Standard. I was looking at the machine and he came out and said ‘You wanna ride, Red?’ I had never been on a motorcycle but I had a lot of confidence in most anything. So I pedaled the thing down the street and took off. I was quite thrilled.” The thrill never went.

After his family moved to Stockton, California, Dudley began working during school vacations for an Indian dealer. On May 10, 1911, “Red” entered his first race, a Stockton mile. Riding an Indian, he won.

After his step-mother died (Dud’s natural mother died when he was a year-and-a-half), he moved in with his grandmother and uncle on a farm in Rocklin, a town in the hot flatlands north of Sacramento. Dud’s father was a railroad man. He had to move with the job often, so the farm was the only place for a boy to settle during his school days. Dud divvied his time between school, farm chores, a night job and his Excelsior (with the motorcycle receiving an unequal portion).

When his father was transferred to San Francisco, Dud quit high school and went along.

“Hap Alzina had charge of the parts department for the Indian branch in San Francisco,” he says. “I hung around there until he got tired of feeding me, so he got me a job in the Jerome Garage. It was famous in its day because it was used for the storage of chauffeur-driven automobiles, such as Pierce Arrows. .. . Worked about six months there. Lost my week’s pay every week by playing blackjack with the chauffeurs who were a lot smarter than I was.

“Then I went to work for one of San > Francisco’s oldest dealers at that time, Gus Shelane.”

Dud learned the art of motorcycle maintenance by doing. And, as always, he raced. Competing with a strippedstock Excelsior, he won consistently.

AÍ Maggini was the San Francisco dealer for the DeLuxe motorcycle in the century’s early years. He was casting about for a new business partner when he met Dud. The proposition sounded good. Agreements were reached, right hands clasped, a contract was signed. Dudley was in retail. But two years later, profits were still elusive.

“Finally,” Dud says, “my girlfriend, whom I later married, kept bugging me because I wanted to get married. She said, ‘I’m making $100 a month as a librarian and you only make $80 a month. Until you can come up with something more promising, I don’t think we should get married. I made a deal with AÍ to take over the business and assume the debts. From then on, it was Dudley Perkins Company. We started selling Harley-Davidsons, DeLuxes, and Jeffersons.. ..”

But mostly Harleys. Dud says, “The first year I sold 125 of those Harley two-speeds myself. Took care of the shop, AÍ stayed on as the businessman. He wrote the figures, but they were not too impressive.”

The Company survived, but before it could thrive, it needed capital.

Dud explains, “The first World War came along and I had suffered a bad attack of tonsillitis, which left me with inflammatory rheumatism. I was classified 4-F. Anyway, all the young fellas with motorcycles were either drafted or enlisted. And in a panic sell, they came in and sold their machines for whatever I could afford to pay them. The factory went 100 percent government. The Army was taking their entire supply. We couldn’t get any new machines. So I bought all the machines I could. We reconditioned those and sold them for a fair price. That’s how I got the first backlog of money to operate with any degree of volume. ...”

“It goes into World War II. We moved to 655 Ellis Street in December, 1940. All during the period of World War II the government was emulating Germany in that they expected to establish a blitzkrieg of motorcycles. As I recall it, Walter Davidson told me that the walls were bulging back there.

“About the time they were ready to use these machines actively overseas, the thing changed. The Germans quit using them for machines similar to our Jeep. Then the Jeep came into the picture and that stopped all the motorcycles. So these machines were backlogged all over the country in lots, just laying there. In as much as we couldn’t get any new machines, the dealers were offered the opportunity of buying the government stuff.”

He continues, “The other dealers thought I was crazy. I went all over the country, to Louisiana and Texas and bought five carloads in 1944. We paid an average of $125 for them. Ran them through the paint shop, because they were battered and Army drab. We sold them for $325 (the government’s ceiling price). That year was the biggest year, outside of lately, that we’ve had. We actually made, in 1945, $90,000 net profit. All on the sales of used machines.”

The business flowered. Soon, the blossom required larger quarters. That’s been the story five times. The current outlet is a three-story building housing a showroom, about 20 employees, and a second-story service area reached by a ramp. Harley’s massive wares dominate the well-scrubbed showroom.

A keen businessman, Dudley has land investments throughout Frisco. He also has interests in several hotel chains and various other concerns.

When the California Highway Patrol’s motorcycle division was being formed back in the ’30s the keen businessman was there to equip the proposed 225-machine force. But there were contenders. Vying were Indian and Henderson, both four-bangers. “The Indians and Hendersons run smoother,” some argued. But Harley-D’s Twin-Vs would cost half as much to run and maintain, Dudley countered. “I told the state they were buying miles,” he says simply. Dudley’s eloquence won. Harley would equip the fledgling agency.

T days I HOUGH of motorcycling-before DUD raced in the hairy durable tires, adequate brakes, helmets and pain were invented—he’s never been seriously injured. Only several broken bones in almost 70 years of street and competitive motorcycling.

“I quit dirt track before I got married, in 1914,” he says. “My wife took a very dim view of motorcycle racing. I took her to a race meet this one time and there was a boy killed. She had an agreement with me that I would quit racing. Coupla times I sneaked out. One time I won a 50-mile track race at Bakersfield, on an Indian. She had a girlfriend down there. The girlfriend visited her and said, T see your redheaded boy did quite well at Bakersfield.’ That really put me on the spot. But for all intents and purposes, I quit dirt track in 1914. In 1915 I started hillclimbing. .. .”

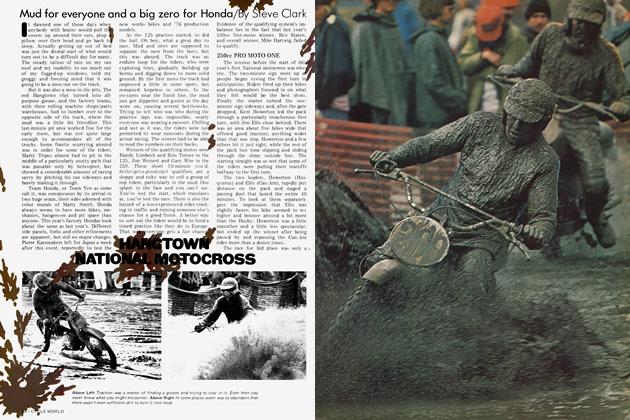

Dudley was a skyrocket on the slopes. He was the West Coast National Hillclimb Champion for 10 years. Those vintage magazines have photos of Dud doing wheelies up hills on motorcycles that look like crosses between enraged scorpions and belligerent Schwinns. In the late `20s he took a brief hiatus from hillclimbing. But he was soon back on unlevel ground, and remained un beaten until his ultimate retirement in the `30s.

(Continued on page 83)

Continued from page 41

His competition with the legendary Floyd Clymer was good-natured and white-hot intense. "I climbed in Denver, Floyd's hometown," Dud says. "I'd always beat him. Floyd and I had a standing bet for the Capistrano meets of $100. It wasn't Floyd against me but me against the entire field. I took 100 bucks every time I went, except once in one event. That was in 1922, I think."

Remember that ancient film of a passenger climbing from a motorcycle onto a rope ladder hanging from an airplane-all while doing about 75 mph? Dudley was the bike's pilot.

"It was 1919," he says. "There was an aviator and a wing-walker. He rigged up this stunt where he was gonna let down a rope ladder while out on the Beach Highway (it's the Great Highway, in San Francisco), and I was gonna have this man on my tandem. He was sup posed to be picked up. I had a top speed of 90 mph. The guy was supposed to get low with the plane and drop the ladder, the guy on the tandem would grab it and start up, and I'd run out from under them.

"The first time we did it, there had been no provision made for the addi tional weight he would put on the plane. So when he got on the ladder the plane sunk a little bit and dragged him about 100 feet on his back. Finally, he got up. We did it twice. This tandem had an extended step. I've thought since then that if that rope ladder had caught on that step. . . ."

Dudley broad-jumped motorcycles, too, upstaging the Einhorns, Lawlers and Knievels by decades. He still carries the scalp wound from one crash landing.

UDLEY REMEMBERS motorcy cling in the century's dawn as being done by a "close-knit group of people. It was mainly a family activity, like men taking their wives on picnic outings. They used sidecars a lot. Motorcycles and sidecars at that time were affordable for the man who couldn't afford a car (those days may be here again!). Oh, there were the individ ual outlaws. In a small way, they caused a lot of ruckus. I remember a kid we used to call Crazy Mac. He was an absolute screwball on a motorcycle. Just one of those ornery kids. But by and large, until that fracas at Hollister and the bad publicity that was bound to happen, I would say it was no different than other sports.”

(Continued on page 84)

Continued from page 83

The Company has sponsored dozens of racers. Today, with the new helm, that tack has slackened. Still, one of the best racers charges from The Company’s portals: Mert Lawwill. Dud says, “Probably the best all-around racer, a perfect gentleman and an able mechanic. But Brelsford is a better road racer.” Mark Brelsford, the young man with startling talent, was one of The Company’s streaking crew. But because of equally startling bad luck—enough race injuries to make even an ambulance driver turn green—Mark has retired from racing.

Racing, more so than street riding probably, is what Dudley loves. He comments, “Everything has grown so fast in the last five years that we’ve reached uncontrollable speeds. Our speeds are in excess, I think, of the ability of a human, regardless of how good he is, to avoid certain circumstances. The tires are right on the edge. Speeds of 200 mph are ridiculous. It doesn’t make for a safe race or for good competition. I see some sort of limit coming from the AMA for safety’s sake. I would say the maximum speed should be 175 mph, tops. Anyway, I think the best racing we ever had was in the 150-mph range.

“It really is essential and necessary to give the whole competitive picture a new look, a good look. To see where we’re going to stop before we kill too many of our boys.”

He continues, “We have to maintain a good image on the street, too. Noise. That’s a big problem now. I think there will be more anti-noise legislation. It’ll be good. I think it’s been carried too far at the track. Noise contributes to a race from the spectators’ point-of-view. But anti-noise legislation for street and offroad riding will be good.”

During 1973’s fuel crisis, dealers were deluged with business. The Company sold 65 big Harleys in one week, for example.

“Business boomed,” Dud understates. “For motorcycles, another definite fuel crisis will be good. . . .1 think we need to go further with development.

“For example, I think we need automatic transmission, to make riding more convenient. You know, I think scooters will make a comeback. They’re ideal for in-town commuting, even better than motorcycles. We need more development and the industry could probably use a Ralph Nader. I don’t think we have one yet, but it’d be a good thing.”

Ask Dud what he feels is the best motorcycle safety device. “The modern safety helmet,” he’ll say. He doesn’t wear one. For all his business errands around town, he rides his Topper, a scooter with an automatic transmission discontinued in 1965.

“Let’s say,” he says, “I’m one of the old school. I’ve never felt I’d get myself in a spot where I needed a helmet. I guess there’s a little pride attached to it. I ride in my business suit and my business hat and that’s it. I think it’s an image worth preserving, but I know it’s not the safest one in the world.”

Then he adds, “Really, I could get knocked off. But actually, I can’t see any excuse for anyone who has a head on their shoulders to get into trouble on a motorcycle. He’s got to ride ahead of himself. Watch every situation, keep his mind on the job. Even at my age, I forget everything else when I’m on that scooter.”

Even at my age? Doesn’t Dudley know he’s ageless? And get into trouble on a motorcycle? The wheels of fate wouldn’t dare. m

View Full Issue

View Full Issue