MARK BRELSFORD

An empty season

ED REMITZ

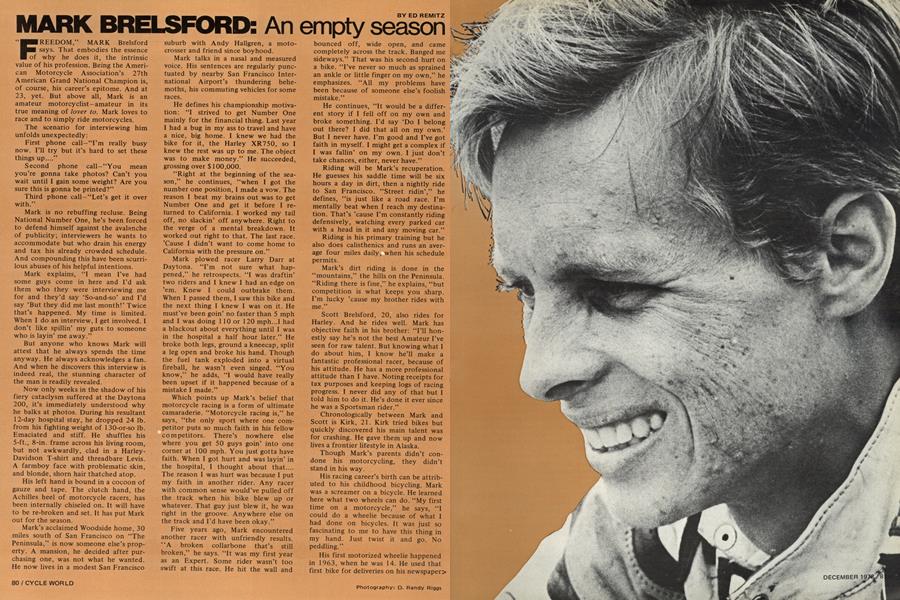

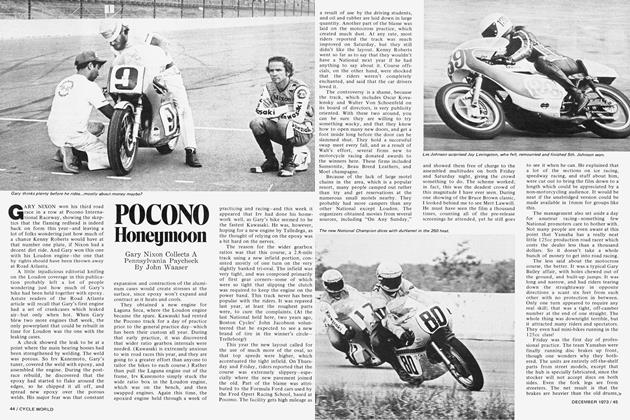

"FREEDOM,” MARK Brelsford says. That embodies the essence of why he does it, the intrinsic value of his profession. Being the American Motorcycle Association’s 27th American Grand National Champion is, of course, his career’s epitome. And at 23, yet. But above all, Mark is an amateur motorcyclist—amateur in its true meaning of lover to. Mark loves to race and to simply ride motorcycles.

The scenario for interviewing him unfolds unexpectedly:

First phone call—“Fm really busy now. I’ll try but it’s hard to set these things up....”

Second phone call—“You mean you’re gonna take photos? Can’t you wait until I gain some weight? Are you sure this is gonna be printed?”

Third phone call—“Let’s get it over with.”

Mark is no rebuffing recluse. Being National Number One, he’s been forced to defend himself against the avalanche of publicity; interviewers he wants to accommodate but who drain his energy and tax his already crowded schedule. And compounding this have been scurrilous abuses of his helpful intentions.

Mark explains, “I mean I’ve had some guys come in here and I’d ask them who they were interviewing me for and they’d say ‘So-and-so’ and I’d say ‘But they did me last month!’ Twice that’s happened. My time is limited. When I do an interview, I get involved. I don’t like spillin’ my guts to someone who is layin’ me away.”

But anyone who knows Mark will attest that he always spends the time anyway. He always acknowledges a fan. And when he discovers this interview is indeed real, the stunning character of the man is readily revealed.

Now only weeks in the shadow of his fiery cataclysm suffered at the Daytona 200, it’s immediately understood why he balks at photos. During his resultant 12-day hospital stay, he dropped 24 lb. from his fighting weight of 130-or-so lb. Emaciated and stiff. He shuffles his 5-ft., 8-in. frame across his living room, but not awkwardly, clad in a HarleyDavidson T-shirt and threadbare Levis. A farmboy face with problematic skin, and blonde, shorn hair thatched atop.

His left hand is bound in a cocoon of gauze and tape. The clutch hand, the Achilles heel of motorcycle racers, has been internally chiseled on. It will have to be re-broken and set. It has put Mark out for the season.

Mark’s acclaimed Woodside home, 30 miles south of San Francisco on “The Peninsula,” is now someone else’s property. A mansion, he decided after purchasing one, was not what he wanted. He now lives in a modest San Francisco suburb with Andy Hallgren, a motocrosser and friend since boyhood.

Mark talks in a nasal and measured voice. His sentences are regularly punctuated by nearby San Francisco International Airport’s thundering behemoths, his commuting vehicles for some races.

He defines his championship motivation: “I strived to get Number One mainly for the financial thing. Last year I had a bug in my ass to travel and have a nice, big home. I knew we had the bike for it, the Harley XR750, so I knew the rest was up to me. The object was to make money.” He succeeded, grossing over $100,000.

“Right at the beginning of the season,” he continues, “when I got the number one position, I made a vow. The reason I beat my brains out was to get Number One and get it before I returned to California. I worked my tail off, no slackin’ off anywhere. Right to the verge of a mental breakdown. It worked out right to that. The last race. ’Cause I didn’t want to come home to California with the pressure on.”

Mark plowed racer Larry Darr at Daytona. “I’m not sure what happened,” he retrospects. “I was draftin’ two riders and I knew I had an edge on ’em. Knew I could outbrake them. When I passed them, I saw this bike and the next thing I knew I was on it. He must’ve been goin’ no faster than 5 mph and I was doing 110 or 120 mph...I had a blackout about everything until I was in the hospital a half hour later.” He broke both legs, ground a kneecap, split a leg open and broke his hand. Though the fuel tank exploded into a virtual fireball, he wasn’t even singed. “You know,” he adds, “I would have really been upset if it happened because of a mistake I made.”

Which points up Mark’s belief that motorcycle racing is a form of ultimate camaraderie. “Motorcycle racing is,” he says, “the only sport where one competitor puts so much faith in his fellow competitors. There’s nowhere else where you get 50 guys goin’ into one corner at 100 mph. You just gotta have faith. When I got hurt and was layin’ in the hospital, I thought about that.... The reason I was hurt was because I put my faith in another rider. Any racer with common sense would’ve pulled off the track when his bike blew up or whatever. That guy just blew it, he was right in the groove. Anywhere else on the track and I’d have been okay.”

Five years ago, Mark encountered another racer with unfriendly results. “A broken collarbone that’s still broken,” he says. “It was my first year as an Expert. Some rider wasn’t too swift at this race. He hit the wall and bounced off, wide open, and came completely across the track. Banged me sideways.” That was his second hurt on a bike. “I’ve never so much as sprained an ankle or little finger on my own,” he emphasizes. “All my problems have been because of someone else’s foolish mistake.”

He continues, “It would be a different story if I fell off on my own and broke something. I’d say ‘Do I belong out there? I did that all on my own.’ But I never have. I’m good and I’ve got faith in myself. I might get a complex if I was failin’ on my own. I just don’t take chances, either, never have.”

Riding will be Mark’s recuperation. He guesses his saddle time will be six hours a day in dirt, then a nightly ride to San Francisco. “Street ridin’,” he defines, “is just like a road race. I’m mentally beat when I reach my destination. That’s ’cause I’m constantly riding defensively, watching every parked car with a head in it and any moving car.”

Riding is his primary training but he also does calisthenics and runs an average four miles daily, when his schedule permits.

Mark’s dirt riding is done in the “mountains,” the hills on the Peninsula. “Riding there is fine,” he explains, “but competition is what keeps you sharp. I’m lucky ’cause my brother rides with me.

Scott Brelsford, 20, also rides for Harley. And he rides well. Mark has objective faith in his brother: “I’ll honestly say he’s not the best Amateur I’ve seen for raw talent. But knowing what I do about him, I know he’ll make a fantastic professional racer, because of his attitude. He has a more professional attitude than I have. Noting receipts for tax purposes and keeping logs of racing progress. I never did any of that but I told him to do it. He’s done it ever since he was a Sportsman rider.”

Chronologically between Mark and Scott is Kirk, 21. Kirk tried bikes but quickly discovered his main talent was for crashing. He gave them up and now lives a frontier lifestyle in Alaska.

Though Mark’s parents didn’t condone his motorcycling, they didn’t stand in his way.

His racing career’s birth can be attributed to his childhood bicycling. Mark was a screamer on a bicycle. He learned here what two wheels can do. “My first time on a motorcycle,” he says, “I could do a wheelie because of what I had done on bicycles. It was just so fascinating to me to have this thing in my hand. Just twist it and go. No peddling.”

His first motorized wheelie happened in 1963, when he was 14. He used that first bike for deliveries on his newspaper> route. Competition soon followed.

Press reports have had it that Mark beat Dick Mann at a Cow Bell Enduro, when Mark was only 15. “That was exaggerated,” Mark reports. “I was cuttin’ a good trail, wide open, and might have come bombin’ through a good spot one time. You know, I saw Dick Mann and thought ‘He’s settin’ the pace. Run over him!’ And he just thinks ‘Who cares. I’m riding for fun.’ This happens to me all the time now. I come home from ridin’ in the mountains and I find I was blown off by so-and-so and I didn’t even know I was racin’.” But Mark confirms the report that he rode a full-street Honda 160 in the 90-mile enduro.

And cars: “I have no intentions whatsoever of racing cars. Never have. As publicity for the sport, he explains, an announcement was made to the motorsport press that he wanted to race cars but found motorcycle racing too lucrative. Just common promotional flak. “I could give a shit about cars,” he says and grins.

Mark began inhabiting local bike shops. Six months later, his persistence paid off. He became a gopher for a Honda-Triumph shop. His motorcycle education formally began. “A guy there,” he says, “Tommy Clark, kinda took a likin’ to me. He used to take me to races. So I was introduced to Class C racing before I ever saw a Sportsman race. I watched a few. They dazzled me.

I didn’t think there was anybody around at that time that was quicker than me. They looked quicker. Looked dangerous. So I just stayed away from that. Then I joined a junior bike club in Daly City. At one of these meetings, it was announced there was gonna be a Sportsman race. Everybody raised their hands to go so I did, too. To not be left out.”

Mark ended up leaving them all behind. For years he rode Sportsman scrambles races. He struggled through poor times and poorer equipment. But paying his dues began to register a profit.

He met Jimmy Odom, who offered priceless advice. He got better equipment. And he raced a Harley.

They recognized a man with the knack. In 1969, Harley took Mark under its black-and-orange wing.

“Harley-Davidson was the big thing for me,” Mark says. “Cubic money, as Dick O’Brien says. Harley is different from other teams because it’s somewhat of a family affair. O’Brien said in my first year, for example, ‘We don’t expect any miracles the first year. Just stay in one piece and learn. Learn how to ride.’ ”

O’Brien is the Harley team manager. “Marcus Wobbly, O’Brien calls me,” Mark says with undiluted affection. “And I’m not sure why.... You just can’t beat him. But I didn’t like him at first. He’s the type of guy who’d tell ya somethin’ and you’d go away swearin’. Like a mean schoolteacher. But then you’d realize a few weeks later that what he told you was worthwhile. I rode for him but I didn’t like his attitude. I always thought he was on me. But then it was like a big puzzle, everything went together. Pretty soon I found out this guy was wunnerful.”

By joining the Harley team, Mark simultaneously met two people to whom he attributes much of his success.

“Mert Lawwill, you might say,” Mark says, “tutored me. Taught me professionalism and strategy.”

The other half: “Jim Belland is the key man,” Mark emphasized, “behind my Number One. With his knowledge of frame geometry and mechanics, we didn’t have any failures.”

Jim Belland shrugs at providing an exact title. “Tuner, I guess,” he says. “Sometimes Mark introduces me as ‘Jim Belland, my tuner and friend.’ That’s important to me.”

Jim is a salesman for Dudley Perkins Harley-Davidson, probably the oldest bike dealer in the San Francisco area. At 35 years old, he’s sold Harleys for 15 years. But Jim has never cranked a wrench for the shop. He learned his craft, which he calls a hobby, out of his own interest and experience. “If I was a mechanic for a living,” he laughs, “I wouldn’t want to work on these things all evening every evening practically.”

He describes what he does: “For example, this last year I traveled every weekend of racing to take care of what was needed. I would come home from work, eat dinner, then go out in the garage and work ’til midnight or 1 or 2 am. Then I’d fly to the race with the engine or transmission or frame or whatever.” He adds wryly, “We disagree with the factory on frame geometry. Our motorcycles handle well.”

Jim lives in Pacifica, a coastal town not far from Mark’s home, with wife Wanda and his four children. Wanda, only with us long enough to insist I eat dinner, must be a right arm for helping Jim and his exhausting “hobby.”

Belland’s garage only resembles same by facade. A drafting table, lathes, welding equipment and more exotic tools inhabit it. Here he does maintenance and designs and builds Mark’s frames. Many of his frame innovations have been picked up by Harley for its factory machines.

Jim is a biologist by education. He’s only a few units short of a degree. “I decided,” he says, “I didn’t want to be a teacher, which is about the only thing you can do with a biology degree.” So it isn’t directly evident why he shifted from dissecting frogs to drag racing cars for years and, finally, settled on motorcycles. Whatever the reasons. Mark couldn’t be less interested or more happy that he did.

Jim dispells a common notion: “A lot of people thought we were heavily financed by the factory but that’s not the case. For me to fly to the races, Mark had to make a lot of money.”

He continues, “The phenomenon of the Harley racing team. Road racers are supplied by the factory, built, crewed and everything. Cal Rayborn is the top road racer so everyone under him gets the lesser equipment, he gets the best. But the dirt equipment, well you’re handed a new racing dirt motorcycle and they say ‘Call us when you need something.’ You’re on your own. So you can experiment in any way you want. Road racing is boiling down, though, to full factory support for Calvin and Mark only.”

Jim reiterates what Mark says of Harley’s team management. He says, “A family organization? Yeah, there’s a lot of things that go on that if it were a business arrangement, they wouldn’t. Like if a rider has a drought, they’ll keep him around and give him test riding or something else to do. They don’t exploit their riders, they take good care of them.”

With the championship his, the absolute natural mastery Mark holds over a motorcycle is a matter of record. Citing several examples of Mark’s artistry, Jim says, “At one 15-lap Main event he fell down two laps out. He got his foot caught in the rear wheel which took him two laps to get out. He got up and in the remaining 11 laps gained back the two laps and got sixth. In another lap he would’ve won it...Mark is a fighter. He could be dead last and he’d still be battling the next to dead last. If it took him 20 laps to do it, he’d do it. Fortunately, he has an uncanny ability to go awfully fast. He’s done things I’ve never seen anybody else do without falling.”

Jim continues, illustrating with his hands what Mark does on a bike, “A good example is at the Ascot TT coming out of the back stretch on a real slow turn. He’ll run into the thing and drop it on the crankcases and turn the front wheel in, with the brake locked, pushing a mound of dirt ahead of him. We couldn’t believe it ’til we saw the pictures. He says he has lots of confidence in the motorcycle. He says it just can’t fall, he just turns the throttle on and it picks itself up and goes. It’s just that confidence. And not cockiness, just a quiet knowing he can do it.”

It’s that element of confidence, more than courage or balance and timing, that makes a brilliant racer, Jim feels.

Did Mark’s championship quest really drive him to the mental limit? “But that’s what it takes,” Jim replies. “You have to want that so bad that everything else is secondary. Anything with value in the past. Family, relationships. You have to have that one goal in life.... He got to where he wouldn’t talk to people. He never got to the point, though, where he was hard to live with. And I think that’s where he’s got it over every other racer I’ve known. He can have major problems where other people would fly to pieces. He’ll just grit his teeth and work around ’em.”

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 83

Jim feels Mark’s racing expertise has yet to peak. He explains, “Mark is rapidly approaching the point where he can go as fast or faster than Cal Rayborn, whose forte is road racing. But only sporadically. It’s just Mark’s inexperience, he’s young. I think that with another year’s riding, you’re going to see Mark one of the top road racers in the world. Right now he’s capable of beating Calvin if it came down to a last lap, right there with him, and it takes a lap to do it. Mark could. But if it took another lap, Calvin would do it. He’s got the edge. A fine craftsman....

“Mark is the closest thing to Carroll Resweber in riding style I’ve ever seen. Carroll was mainly concerned with getting traction. If the bike steered well in the corner after that, that was fine. If not, he could contend with it. Mark is like that.”

Mark’s future in motorcycle racing is not certain. Jim says, “You know Mark’s father was a ski instructor in Yosemite National Park. Mark was born there. Well he’s always had a thing for the outdoors. Kirk lives in the woods of Alaska. Mark wants to do something like that, be a lumberjack or forest ranger. If he wants to do it, I’m sure he will. He won’t be a racer the rest of his life.”

Racing for racing’s sake enriches Mark’s life. “Competition,” he says, “stimulates me. It makes me a better person as a whole. It gives me a lot of drive. I don’t like to lose, to be 2nd. It makes me analyze and discover what I did wrong. It gives me a lot of satisfaction.”

But as Jim said, Mark says his life will not necessarily revolve around motorcycles always. He will find satisfaction elsewhere, too. He does talk of being a lumberjack in South America or living a rugged, outdoor life one day.

That’s for the distant future, though. Today Mark endures the mandatory vacation born of his injured hand. Resignedly, he says, “Well at least I’ll get to do some of the things I want to do....”

Jim Beiland says, “This rest will be all for the good. I think he needs to be out for the season to rest and take time to enjoy what he loves best, riding a motorcycle.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue