THE WAY WE WERE

Jerry Hatfield

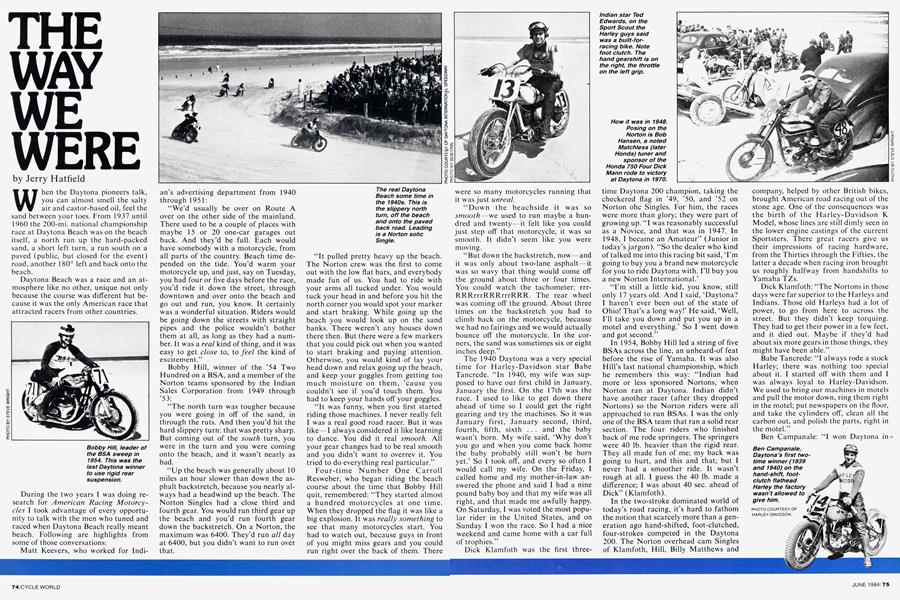

When the Daytona pioneers talk, you can almost smell the salty air and castor-based oil, feel the sand between your toes. From 1937 until 1960 the 200-mi. national championship race at Daytona Beach was on the beach itself, a north run up the hard-packed sand, a short left turn, a run south on a paved (public, but closed for the event) road, another 180° left and back onto the beach.

Daytona Beach was a race and an atmosphere like no other, unique not only because the course was different but because it was the only American race that attracted racers from other countries.

During the two years I was doing research for American Racing Motorcycles I took advantage of every opportunity to talk with the men who tuned and raced when Daytona Beach really meant beach. Following are highlights from some of those conversations:

Matt Keevers, who worked for Indi-

an’s advertising department from 1940 through 1951:

“We’d usually be over on Route A over on the other side of the mainland. There used to be a couple of places with maybe 15 or 20 one-car garages out back. And they’d be full. Each would have somebody with a motorcycle, from all parts of the country. Beach time depended on the tide. You’d warm your motorcycle up, and just, say on Tuesday, you had four or five days before the race, you’d ride it down the street, through downtown and over onto the beach and go out and run, you know. It certainly was a wonderful situation. Riders would be going down the streets with straight pipes and the police wouldn’t bother them at all, as long as they had a number. It was a real kind of thing, and it was easy to get close to, to feel the kind of excitement.’’

Bobby Hill, winner of the ’54 Two Hundred on a BSA, and a member of the Norton teams sponsored by the Indian Sales Corporation from 1949 through

’53:

“The north turn was tougher because you were going in off of the sand, in through the ruts. And then you’d hit the hard slippery turn: that was pretty sharp. But coming out of the south turn, you were in the turn and you were coming onto the beach, and it wasn’t nearly as bad.

“Up the beach was generally about 10 miles an hour slower than down the asphalt backstretch, because you nearly always had a headwind up the beach. The Norton Singles had a close third and fourth gear. You would run third gear up the beach and you’d run fourth gear down the backstretch. On a Norton, the maximum was 6400. They’d run all day at 6400, but you didn’t want to run over that.

“It pulled pretty heavy up the beach. The Norton crew was the first to come out with the low flat bars, and everybody made fun of us. You had to ride with your arms all tucked under. You would tuck your head in and before you hit the north corner you would spot your marker and start braking. While going up the beach you would look up on the sand banks. There weren’t any houses down there then. But there were a few markers that you could pick out when you wanted to start braking and paying attention. Otherwise, you would kind of lay your head down and relax going up the beach, and keep your goggles from getting too much moisture on them, ’cause you couldn’t see if you’d touch them. You had to keep your hands off your goggles.

“It was funny, when you first started riding those machines. I never really felt I was a real good road racer. But it was like—I always considered it like learning to dance. You did it real smooth. All your gear changes had to be real smooth and you didn’t want to overrev it. You tried to do everything real particular.”

Four-time Number One Carroll Resweber, who began riding the beach course about the time that Bobby Hill quit, remembered: “They started almost a hundred motorcycles at one time. When they dropped the flag it was like a big explosion. It was really something to see that many motorcycles start. You had to watch out, because guys in front of you might miss gears and you could run right over the back of them. There were so many motorcycles running that it was just unreal.

“Down the beachside it was so smooth we used to run maybe a hundred and twenty—it felt like you could just step off that motorcycle, it was so smooth. It didn’t seem like you were moving.

“But down the backstretch, now—and it was only about two-lane asphalt—it was so wavy that thing would come off the ground about three or four times. You could watch the tachometer: rrrRRRrrrRRRrrrRRR. The rear wheel was coming off the ground. About three times on the backstretch you had to climb back on the motorcycle, because we had no fairings and we would actually bounce off the motorcycle. In the corners, the sand was sometimes six or eight inches deep.”

The 1940 Daytona was a very special time for Harley-Davidson star Babe Tancrede. “In 1940, my wife was supposed to have our first child in January, January the first. On the 17th was the race. I used to like to get down there ahead of time so I could get the right gearing and try the machines. So it was January first, January second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth . . . and the baby wasn’t born. My wife said, ‘Why don’t you go and when you come back home the baby probably still won’t be born yet.’ So I took off, and every so often I would call my wife. On the Friday, I called home and my mother-in-law answered the phone and said I had a nine pound baby boy and that my wife was all right, and that made me awfully happy. On Saturday, I was voted the most popular rider in the United States, and on Sunday I won the race. So I had a nice weekend and came home with a car full of trophies.”

Dick Klamfoth was the first threetime Daytona 200 champion, taking the checkered flag in ’49, ’50, and ’52 on Norton ohc Singles. For him, the races were more than glory; they were part of growing up. “I was reasonably successful as a Novice, and that was in 1947. In 1948, I became an Amateur” (Junior in today’s jargon). “So the dealer who kind of talked me into this racing bit said, ‘I’m going to buy you a brand new motorcycle for you to ride Daytona with. I’ll buy you a new Norton International.’

“I’m still a little kid, you know, still only 17 years old. And I said, ‘Daytona? I haven’t ever been out of the state of Ohio! That’s a long way!’ He said, ‘Well, I’ll take you down and put you up in a motel and everything.’ So I went down and got second.”

In 1954, Bobby Hill led a string of five BSAs across the line, an unheard-of feat before the rise of Yamaha. It was also Hill’s last national championship, which he remembers this way: “Indian had more or less sponsored Nortons, when Norton ran at Daytona. Indian didn’t have another racer (after they dropped Nortons) so the Norton riders were all approached to run BSAs. I was the only one of the BSA team that ran a solid rear section. The four riders who finished back of me rode springers. The springers were 40 lb. heavier than the rigid rear. They all made fun of me; my back was going to hurt, and this and that; but I never had a smoother ride. It wasn’t rough at all. I guess the 40 lb. made a difference; I was about 40 sec. ahead of Dick” (Klamfoth).

In the two-stroke dominated world of today’s road racing, it’s hard to fathom the notion that scarcely more than a generation ago hand-shifted, foot-clutched, four-strokes competed in the Daytona 200. The Norton overhead cam Singles of Klamfoth, Hill, Billy Matthews and company, helped by other British bikes, brought American road racing out of the stone age. One of the consequences was the birth of the Harley-Davidson K Model, whose lines are still dimly seen in the lower engine castings of the current Sportsters. There great racers give us their impressions of racing hardware, from the Thirties through the Fifties, the latter a decade when racing iron brought us roughly halfway from handshifts to Yamaha TZs.

Dick Klamfoth: “The Nortons in those days were far superior to the Harleys and Indians. Those old Harleys had a lot of power, to go from here to across the street. But they didn’t keep torquing. They had to get their power in a few feet, and it died out. Maybe if they’d had about six more gears in those things, they might have been able.”

Babe Tancrede: “I always rode a stock Harley; there was nothing too special about it. I started off with them and I was always loyal to Harley-Davidson. We used to bring our machines in motels and pull the motor down, ring them right in the motel; put newspapers on the floor, and take the cylinders off, clean all the carbon out, and polish the parts, right in the motel.”

Ben Campanale: “I won Daytona in>

’38 and '39; I was the first two-time winner. Of course, they only started it in ’37.

“Babe and 1 used to do all our own work. The motors were stock, at first. The first machines we raced were stock; they were just a road machine. We had to buy them, because that was the AMA rule. You weren’t supposed to be given any motorcycles.

“Indian was way ahead of Harley-Davidson in getting the motors built for racing purposes. They used to build racers in the days when we were riding stock Harley-Davidsons. Indian built real racing machines, the Scouts, and they were real fast machines. The only way you could ever keep up with the Indian was in the big races. In the endurance races, the Harley had it. When Harley-Davidson decided to build a factory racer (in 1941), it was a different story, and we had as much steam as the Indians did, if not more at times.

“The last race I rode was Daytona Beach, in 1950. That’s when I decided to quit. What discouraged me more than anything at that time they had the Nortons going. Our American machines didn’t have a chance with them. I was so disappointed that we didn’t have a machine that would keep up with them. So that’s when I decided there was no sense in fooling around anymore. They had the Isle of Man Norton, you know. They would pull the engines out of the special frames they had for the Isle of Man. And they would put these special engines in the regular frames, so they could get away with it. Oh, those things used to go! On the straightaway you had no chance with those things. The only way you could ever beat them was in the corner, ’cause they never handled as good as the Harley did in the sandy corners. But once they got on that straightaway, they were gone!"

After outclassing the handshift Harleys and Indians, as well as other British bikes, the latest double overhead cam Nortons were barred from the supposedly stock Class C game at the end of 1952. The BSA importer was given false hope by the impressive 1954 five-place sweep, but not even the Harley-Davidson factory’s sponsored riders could beat the brand within a brand, the Sifton-HarleyDavidsons from San Jose, California.

Carrol Resweber knew what it was like to be Number One, and yet be consistently outrun on the beach. “We never did have anything to run with (Brad) Andres and Joe Leonard, ’cause Tom Sifton was helping them and they had horsepower on us. Even back then they were flowing the ports; that’s where we missed the boat. They were superior when it came to horsepower, Joe and Brad Andres; I couldn't even hang their draft. When they'd go by I’d drop in their draft and they’d just suck me right out of it. Without horsepower you were done, there, because there wasn’t that much riding ability needed that you could make up the difference.”

Resweber admits he wasn’t a fan of the beach course. “I didn’t enjoy the beach course because it was too monotonous. There was nothing to do. You’d draft guys like you were running down the salt flats, and that’s no fun, especially if you hadn’t got the horsepower. The new course was, by far, better.”

The beach course was a poor setup for crowd control, a fact which was brought home sadly when a careless pedestrian caused a fatal accident in the ’53 race. Moreover, the lack of crowd control was a bad proposition for the ticket seller. These were the factors which ultimately spelled the end of the old beach course, and not whatever shortcomings the seaside venue had from the racers’ perspective. Regarding the latter point, the purist British sometimes labeled the event a non-race. Yet, when the racing bucks were sufficient, the Norton, BSA, and Triumph factories liked racing along the Atlantic. The British had learned the importance of the American market, making the beach course our first international event, even if such status was not official. And the British factories knew as well as Harley-Davidson that surfside racing made for glamorous publicity photos. And glamorous memories. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

June 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

June 1984 -

History

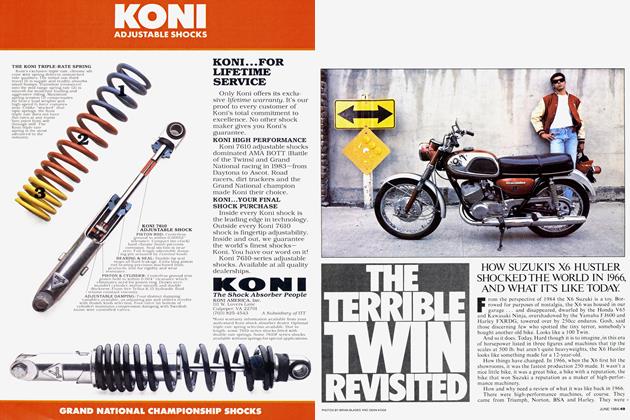

HistoryThe Terrible Twin Revisted

June 1984 -

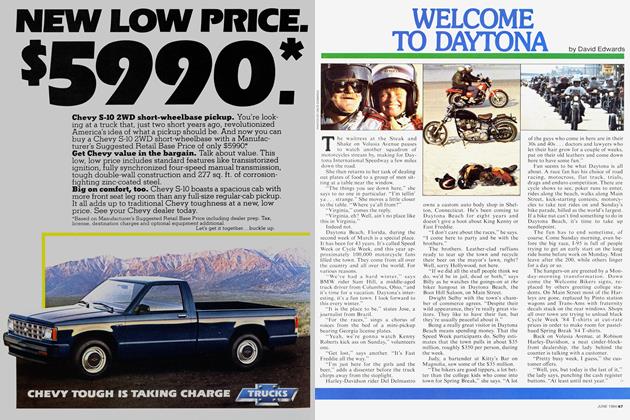

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Welcome To Daytona

June 1984 By David Edwards -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Daytona 200 Roberts' Retirement Win

June 1984 By John Ulrich -

Daytona '84

Daytona '84Bailey Charges To Supercross Win

June 1984