The Final Triumph

England's last hurrah, courtesy of Ray Hensley, C.R. Axtel and Gene Romero

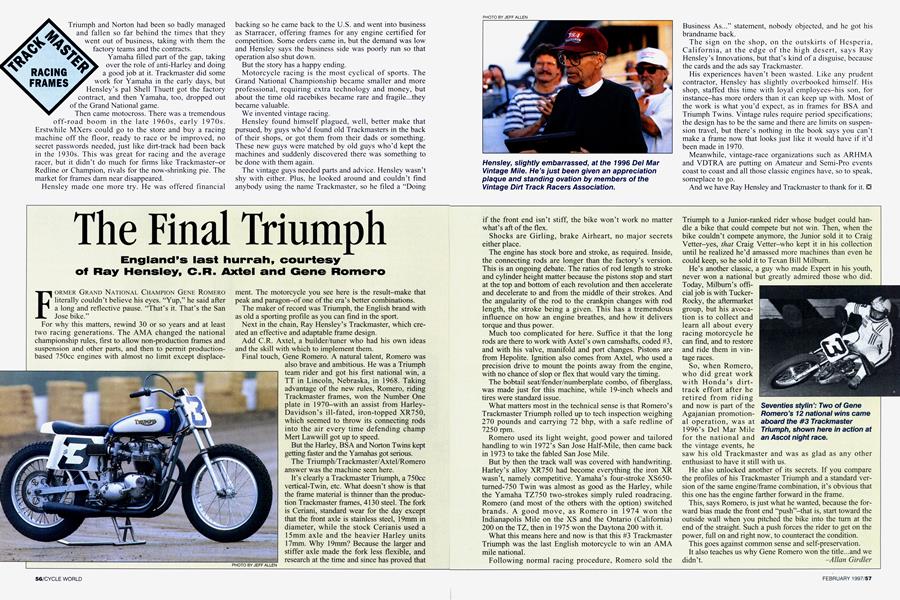

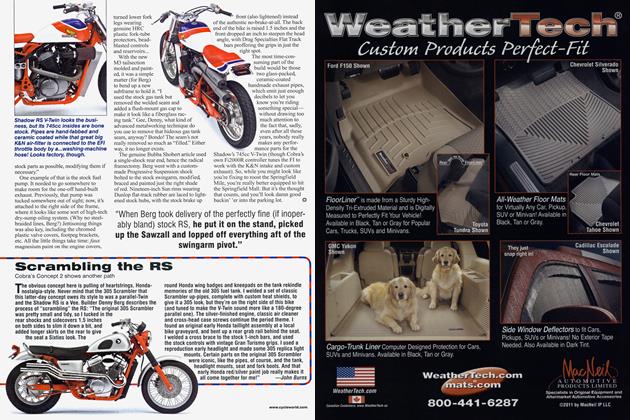

FORMER GRAND NATIONAL CHAMPION GENE ROMERO literally couldn't believe his eyes. "Yup," he said after a long and reflective pause. "That's it. That's the San Jose bike."

For Why this matters, rewind 30 or so years and at least two racing generations. The AMA changed the national championship rules, first to allow non-production frames and suspension and other parts, and then to permit production based 750cc engines with almost no limit except displace-

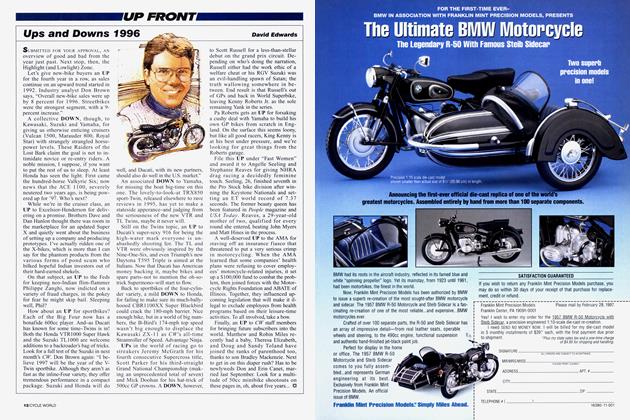

ment. The motorcycle you see here is the result-make that peak and paragon-of one of the era's better combinations.

The maker of record was Triumph, the English brand with as old a sporting profile as you can find in the sport. Next in the chain, Ray Hensley's Trackmaster, which cre ated an effective and adaptable frame design. Add C.R. Axtel, a builder/tuner who had his own ideas and the skill with which to implement them.

Final touch, Gene Romero. A natural talent, Romero was

also brave and ambitious. He was a Triumph team rider and got his first national win, a TT in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1968. Taking advantage of the new rules, Romero, riding Trackmaster frames, won the Number One plate in 1970-with an assist from HarleyDavidson's ill-fated, iron-topped XR750, which seemed to throw its connecting rods into the air every time defending champ Mert Lawwill got up to speed.

But the Harley, BSA and Norton Twins kept getting faster and the Yamahas got serious. The Triumph/Trackmaster/Axtel/Romero answer was the machine seen here.

It's clearly a Trackmaster Triumph, a 750cc vertical-Twin, etc. What doesn't show is that the frame material is thinner than the produc tion Trackmaster frames, 4130 steel. The fork is Ceriani, standard wear for the day except that the front axle is stainless steel, 19mm in diameter, while the stock Cerianis used a 15mm axle and the heavier Harley units 17mm. Why 19mm? Because the larger and stiffer axle made the fork less flexible, and research at the time and since has proved that if the front end isn't stiff, the bike won't work no matter what's aft of the flex. Shocks are Girling, brake Airheart, no major secrets either place.

The engine has stock bore and stroke, as required. Inside, the connecting rods are longer than the factory's version. This is an ongoing debate. The ratios of rod length to stroke and cylinder height matter because the pistons stop and start at the top and bottom of each revolution and then accelerate and decelerate to and from the middle of their strokes. And the angularity of the rod to the crankpin changes with rod length, the stroke being a given. This has a tremendous influence on how an engine breathes, and how it delivers torque and thus power.

Much too complicated for here. Suffice it that the long rods are there to work with Axtel's own camshafts, coded #3, and with his valve, manifold and port changes. Pistons are from Hepolite. Ignition also comes from Axtel, who used a precision drive to mount the points away from the engine, with no chance of slop or flex that would vary the timing.

The bobtail seat/fender/numberplate combo, of fiberglass, was made just for this machine, while 19-inch wheels and tires were standard issue. What matters most in the technical sense is that Romero's Trackmaster Triumph rolled up to tech inspection weighing 270 pounds and carrying 72 bhp, with a safe redline of 7250 rpm.

Romero used its light weight, good power and tailored handling to win 1972's San Jose Half-Mile, then came back in 1973 to take the fabled San Jose Mile.

But by then the track wall was covered with handwriting. Harley's alloy XR750 had become everything the iron XR wasn't, namely competitive. Yamaha's four-stroke XS650turned-750 Twin was almost as good as the Harley, while the Yamaha TZ750 two-strokes simply ruled roadracing. Romero (and most of the others with the option) switched brands. A good move, as Romero in 1974 won the Indianapolis Mile on the XS and the Ontario (California) 200 on the TZ, then in 1975 won the Daytona 200 with it.

What this means here and now is that this #3 Trackmaster Triumph was the last English motorcycle to win an AMA mile national.

Following normal racing procedure, Romero sold the Triumph to a Junior-ranked rider whose budget could han dle a bike that could compete but not win. Then, when the bike couldn't compete anymore, the Junior sold it to Craig Vetter-yes, that Craig Vetter-who kept it in his collection until he realized he'd amassed more machines than even he could keep, so he sold it to Texan Bill Milburn.

He's another classic, a guy who made Expert in his youth, never wona national but greatly admired those who did. Today, Milbum's offi cial job is with TuckerRocky, the aftermarket group, but his avoca tion is to collect and learn all about every racing motorcycle he can find, and to restore and ride them in yin tage races.

So, when Romero, who did great work with Honda's dirttrack effort after he retired from riding and now is part of the Agajanian promotion al operation, was at 1996's Del Mar Mile for the national and the vintage events, he saw his old Trackmaster and was as glad as any other enthusiast to have it still with us.

He also unlocked another of its secrets. If you compare the profiles of his Trackmaster Triumph and a standard ver sion of the same engine/frame combination, it's obvious that this one has the engine farther forward in the frame.

This, says Romero, is just what he wanted, because the for ward bias made the front end "push"-that is, start toward the outside wall when you pitched the bike into the turn at the end of the straight. Such a push forces the rider to get on the power, full on and right now, to counteract the condition.

This goes against common sense and self-preservation. It also teaches us why Gene Romero won the title. ..and we didn't.

Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue