Of Dogs and Deer

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

ACCORDING TO HISTORIANS, MUCH OF the original road system in the U.S. was based on Indian footpaths, which in turn followed ancient game trails. Makes sense to me. Who better than a deer or a pedestrian to find the most sensible path through the wilderness?

Only in recent times has the concept of a frontage road to Wal-Mart overwhelmed the natural logic of the shallow river portage, the unbroken ridgeline or the low-elevation mountain pass. But it seems the roads we re ally like as motorcyclists still follow the old deer trail/Indian tradition of ribbons draped over the land rather than barging through it.

While these roads have their charm, they do present two small problems to the modern rider: 1) A motorcycle trav els a lot faster than a person in moc casins; and 2) the deer have not left.

Indeed, the deer are thriving. In his book, Wildlife in America, Peter Matthiessen says the deer population in the U.S. is now far greater than it was in the day of Daniel Boone, thanks to a ready supply of field corn and a dearth of predators. Deer, in fact, fare much better in the garden-rich envi ronment of suburban America than they do in the lonely north woods. This year we had a record herd in Wiscon sin, 1.7 million. If you don't believe it, ask my friend Bruce Finlayson.

This past summer, he was on a mo torcycle ride at dusk with a bunch of our fellow suspects in the Slimey Crud Motorcycle Gang, cruising a county road not far from Madison, Wisconsin. Suddenly a large white-tail launched itself out of the foliage and landed dead-center in front of his beautifully restored Ducati 750 GT, which was traveling 60-65 mph.

According to eye-witness reports from the five guys who were follow ing, Bruce flew over the top of the deer and tumbled like a rag doll a consider able distance down the road, where his motorcycle slid into him. The deer was killed, and Bruce was unconscious, with a broken collarbone.

From a nearby farmhouse an ambu lance was called, but when it arrived Bruce's blood pressure was dropping and his heart rate was irregular, so the paramedics called a Med-Flight heli copter. By the time the helicopter got there, Bruce had regained conscious ness and was making about as much sense as usual, objecting to the medics cutting his nice old Bates jacket off with surgical scissors.

Thanks to the miracle of modern health-care economics, Bruce was pro nounced fit to return home after only three hours at a Madison Hospital, with a sling on his arm and a prescrip tion for pain-killers.

He's better now, but for weeks he felt pretty battered and beaten up, discov ering new bruises every day. His bike needs the fork straightened, paint and a few random parts, but is entirely fix able. His helmet did its work but is ru ined, with a broken shell and blacktop scars in seven distinct spots. It looks like a cracked eggshell.

A few days after the accident, when Bruce was back up and on his feet, I thought we should celebrate the resurrec tion of the body with a sacramental wine, so of course I took him a bottle of Stag's Leap cabernet. Bruce laughed as only a person with bruised ribs can laugh.

That same week, a woman who works with my wife, Barbara, said her brother hit a deer with his Harley-Davidson (no helmet), spent all night lying in a ditch and was undergoing jaw and facial-bone reconstruction, among other things.

Two weeks later, I was on a ride to the famous Dickeyville Hiliclimb with the same bunch of Cruds who had wit nessed Bruce's accident when a dog the size of a Bultaco Metralla ran in front of my 900SS while I was idly gazing hard right at a beautiful new log home along the road. I never saw the dog until I'd missed it by inches. For the benefit of my co-riders, I grabbed at my heart and put my head down on the tank.

Sheer unvarnished dumb luck. If the dog had been a microsecond slower or the bike had arrived a tick sooner, I'd have had my own Med-Flight ride, and Bruce would have been bringing me a bottle of Red Dog ale.

Mike Puls, who was right behind me, suggested Bruce and I co-write a book called Of Deer and Dogs.

Since then, I've done two smoking emergency stops for deer at night while returning to our rural home from Madison, both of them on Old Stage Road. Which, incidentally, is another of those ancient Indian trails, modern ized to a stagecoach road in the 1 830s and now a fine blacktop motorcycle road. Except for deer.

And they are everywhere this year. There's almost no defense for them after dark, other than doddering slow speed. They appear and disappear like wraiths at night, unpredictable as shoot ing stars or the sudden swoop of an owl.

I haven't yet given up riding at night, but I've certainly slowed. When I ride Old Stage Road at night now, I tend to cruise in the 45-50 mph range, chuff ing along in third gear.

I try to get out of that old cafe racer mode and tell myself I'm on a scenic cruise through a game park, which is almost the truth. I haven't made an evening trip yet this year without see ing at least one deer, three cats, the random dog, a couple of possums and a raccoon or two.

Most of these animals, I'm afraid, are still looking for wolves or humans in moccasins. Nothing in their long evolution has prepared them for the sudden appearance of a fast-moving quartz-halogen headlight from Italy.

Nor in ours, apparently. Our only real advantage in the game of survival seems to be that, like those Indians of yore, we use our trails for trade as well as travel.

Bruce, for instance, had a $400 hel met from Japan and a leather jacket from California, and the deer didn't. But for those two small distinctions, they would both have departed our gene pooi on the same day.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUps And Downs 1996

February 1997 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCReasons To Romp

February 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1997 -

Roundup

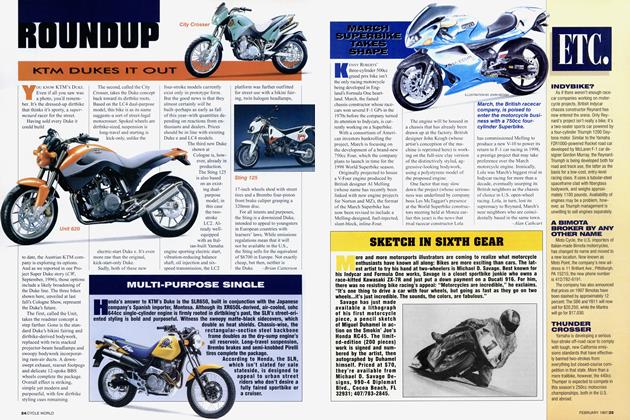

RoundupKtm Dukes It Out

February 1997 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

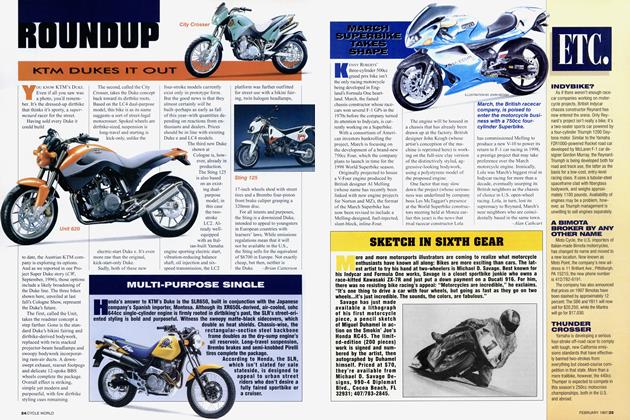

RoundupMulti-Purpose Single

February 1997 -

Roundup

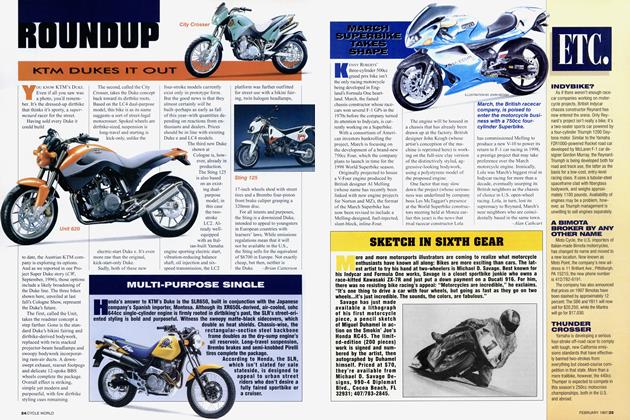

RoundupMarch Superbike Takes Shape

February 1997 By Alan Cathcart