A morning in Italy

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

MY BROTHER BRIAN, WHOSE JOB HAS him traveling even more than mine, and I are solidly agreed on at least one thing: When you arrive in a strange city, the best way to find out where you are-physically and culturally-is to get up early in the morning, leave your hotel and go running and/or walking.

Which is what I did recently in Borgo Panigale, Italy.

Borgo Panigale is the suburb of Bologna where the Ducati factory is situated, and I was there for World Ducati Week, staying at the conveniently close Amadeus Hotel.

While I am not normally an early riser, the usual jet lag tricked me into thinking it was morning at about midnight, so after a largely sleepless night of watching incomprehensible soccer matches and an old John Wayne western dubbed into Italian, I finally threw myself out of bed just before dawn and put on my running shoes.

Hitting the street in front of the hotel,

I headed down the Ave. Marco Emelio Lepido toward the Ducati factory, which was only about five blocks away. The streets were almost empty-Italy is not a country where people feel duty-bound to rise in the dark and rush to work so people will think of them as “team players.” The random Fiat, a few scooters and bicycles went by. A bakery and coffee shop opened its doors and unrolled the awning over its outdoor tables, the aroma of hotbaked bread tumbling out in a thick cloud of seduction. Yet I did not tarry.

Onward I ran, turning onto a narrow sidestreet called Via A. Cavalieri Ducati, past a bus-stop shelter with a big poster of Valentino Rossi holding up a bottle of Nastro Azzuro (Blue Ribbon) beer. Presumably not from Pabst. Will the day ever come in the U.S. when a roadracing hero is a poster boy for a major brand of beer? You’ve got to love Italy.

Inside the guarded gates of the Ducati factory, WDW2002 pennants were flying, rows of 998s, Monsters and STs were poised for our upcoming press ride to the racetrack at Misano on the Adriatic coast, and the walls of the factory were painted with huge murals of the World Superbike team in action.

I trotted as far as I could around the factory grounds without running onto the nearby autostrada, then doubled back and found myself passing Santa Maria Assunta, an old church of faded brick, where bells in the tower began ringing and mostly elderly people converged from different parts of the neighborhood for morning mass.

On the corner, a flower shop was selling bunches of flowers to dozens of old women dressed in black who then made their way by foot or bicycle down a long tree-lined lane to the gates of a walled cemetery. The lane had bronze plaques with flowers on them placed every three feet for its entire length, bearing the names of Borgo Panigale’s war dead from WWI. A lot of casualties for what must have been a very small village in 1918. All the young and fit, the romantic and the energetic. What would it do to a little town like this? Tear the heart out of it, probably. Yet there was quite a bit left. Borgo Panigale, Ducati’s hometown, is to motorcyclists at least a very large part of the heart of Italy.

A man in blue coveralls unlocked the cemetery gates, and the gathered crowd of visitors streamed in. I walked discreetly into the edge of the cemetery and looked around. A huge place, extending behind the church. Some of the tombstones looked very old and weather-beaten, while others followed the 20th-century Italian practice of embedding a photograph of the deceased in the headstone. Not such a bad idea. Seeing the portrait of a son killed in WWII or a mother who has passed away adds a dimension beyond the chiseled name. Faces tell us everything, and contain their own stories.

Strange, but on previous brief visits I’d always thought of Borgo Panigale as a sort of modern, created-from-nothing industrial park, appended to Bologna in the last 50 years or so. But on closer inspection it was an entirely real town with a long history. As a friend of mine once said, “Every acre of Europe has been owned by hundreds and hundreds of generations, going all the way back to Neolithic times, and they’ve all added a little something, or taken something away.”

You could feel that bone-deep age even in the neighborhood around the Ducati factory. In the backyards of nearby homes you saw old wells, fragments of ancient stone walls, gnarled olive trees over tiled patios, roof timbers in barns too large to have come from a modern forest. And in those same backyards were Fiats and Alfa Romeos. And Ducatis. Shiny new things that, nevertheless, managed to look as though they belonged.

As I jogged back to the hotel, traffic was picking up. In the flow were a surprising number of Ducati Monsters. These quick, agile bikes seem to be the new national urban motorcycle of Italy, a high-performance Vespa alternative.

When I got back to the hotel, I showered and went down for breakfast, to get ready for our mass ride from Bologna to Misano. I drank dark roast coffee, ate a typical Italian breakfast of buttery cheese, dark bread and sliced sausage (they don’t call this place Bologna for nothing) and found myself wondering how much my enthusiasm for Italian bikes was derived from the culture that produced them.

Just as every British bike had a certain appealing Druidic content built into its engine and frame, suggesting narrow lanes, greenwood forests and thatched roofs, Ducatis seemed to have evolved naturally from the roads and villages and hills that surround the factory. When you park a red Ducati against a stone wall on the Via Eme lia, it looks perfect, just as a Norton does when it’s parked in front of a half-timbered pub. Not a trace of historical discontinuity.

In the end I decided that, while I like riding motorcycles, I may also be using them to pay homage to foreign places where I feel inexplicably at home. The purchase price is partly tribute, like coins in the collection box when we light a candle in an old cathedral.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Side of Speed

November 2002 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCLiving In Harmony

November 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2002 -

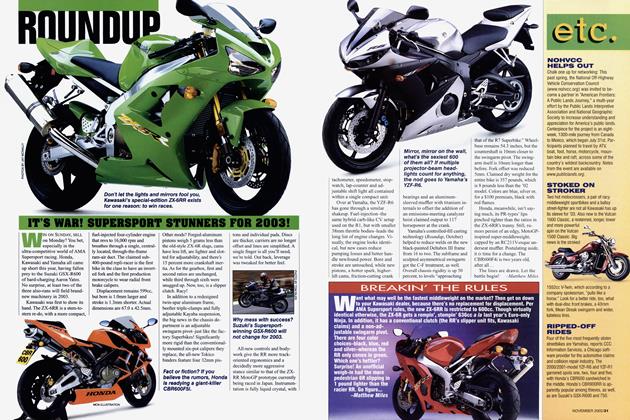

Roundup

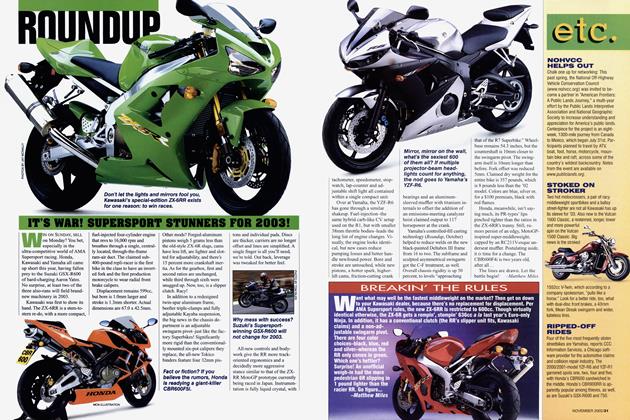

RoundupIt's War! Supersport Stunners For 2003!

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

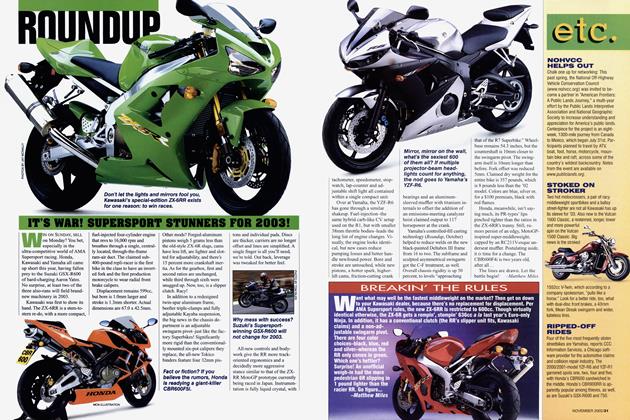

RoundupBreakin' the Rules

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2002