Two-Stroke Underaround

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

IN 1960, THERE WAS NO DOUBT WHO was in charge of U.S. motorcycle competition. It was the established Harley, Triumph and BSA riders and their sponsors, whose justifiably famous names have come down to us through history. Backing them were the only slightly less famous names of Tom Sifton, Jerry Branch, C.R. Axtell and others—the pioneers who ground cams, measured airflow and dyno-bred the horsepower to win. This was a tightknit closed shop—members only. If you were a hot Novice, maybe racing Harley dealer Dud Perkins would give you one of his five-race tryouts. Maybe not.

Plenty was happening outside that small circle of talented and accomplished dirt-track people. Not everyone had the money or know-how to run a pro-built Harley or Triumph, but America was very prosperous, so just about any dad could afford to bring home one of the new “gokarts,” powered by a two-stroke chainsaw engine from McCulloch, Homelite or Power Products. When racing is cheap (a ready-to-run kart for $139.95), anyone with an idea can afford to innovate. Conservatism takes over when racing becomes expensive.

Serious kart racers quickly learned that old-style deflector-piston engines—like the Clinton—couldn’t take the heat. Stock exhaust and transfer ports were rows of holes, but they flowed more when squared off with files. The race for more port area, and more ports, was on. Want extra transfers? Run pieces of half-inch, flexible Tygon tubing between holes drilled in the crankcase and holes drilled in the cylinder, encase the Tygon in Marine-Tex epoxy, let it cure, then pull out the tubing. Kart engines soon had so many ports that almost no cylinder wall was left, and some engines blew in half, breaking on the “dotted line” of ports. Kart racers were making so many experiments that the top runners bought engines by the carton. One such was Erv Kanemoto, who would later win AMA roadrace nationals with Gary Nixon and FIM GPs with Freddie Spencer and Eddie Fawson. Erv’s dad, Harry, had been one of those who brought home a kart to his kids.

Hot-rodder Duffy Fivingstone put a 250cc König racing outboard power-head on his kart, creating a missile. Another, Jim Yamane, adapted one of the strange new Yamaha Twins. Yamaha engines were tried at the Ascot half-mile in 1963 but their power was too explosive. Bultaco dirtbikes were arriving, and people were nine-porting them. Reed valves appeared as if by magic, adapted from saws and Mercury outboards. Another famous name emerged: Dale Herbrandson. Fegend makes him the man who brought reeds and bikes together to stay.

Two-strokes had many attractions. First, anybody could afford them. Second, they annoyed the racing establishment, who dismissed them as "farting in a coffee can." And third, two-strokes were really easy to modify. You didn't need to become courtiers in the halls of airflow or dyno kings. A lathe, a few files and a welding outfit were all it took to reach for power. Two of these experimenters were Gordon Jennings and Bob Braverman. Both would write extensively about their two-stroke work, Braverman in Cycle Guide and Jennings in Cycle World and Cycle, then in his how-to book, The Two-Stroke Tuner~ Handbook.

In 1960, motorsport publishing pioneer Joe Parkhurst became art director for the magazine Karting World, whose issues I devoured when I should have been studying. In its pages I could learn the mysteries of “gulley porting” and read the specs on the new “Standun Supermotor.” The off-highway nature of karting prevented runaway growth, but motorcycles had a big future. Which is why Parkhurst in 1962 went on to create the magazine you are now holding in your hands.

Meanwhile, across the oceans, Honda and Yamaha duked it out in the classic 1960s motorcycle Grand Prix battles. Though one was four-stroke and the other

two-stroke, both were limited by the ideas of their time, and both adopted the same strategy of using more and smaller higherrevving cylinders. Yamaha’s V-Four twostrokes had the same arrangement of one exhaust port and three transfer ports that MZ had defined in 1959. Great refinement was put into this system by intensive R&D; but the more investment a human organization pours into developing an idea, the more valuable it appears and the less likely it is ever to be questioned.

In U.S. karting, everything was questioned, and for the simplest reason. Just when you thought you had the hot setup, someone else’s new ideas would push you over, and you had to start work all over again. It was a wild, creative scene.

Who took the next step? No one knows for sure, but two names are mentioned—Kanemoto and Braverman. Probably there are others I know nothing about. But one or more of these people decided to add more ports to a production-based, two-transfer 1965 Yamaha TD1-B 250cc roadrace engine. The direct way was to cut a shallow trench into the cylinder wall behind each transfer port, fed through matching holes drilled in the piston, emerging above the piston crown at BDC as a second pair of transfer windows.

Somehow, a set of these modified cylinders made its way to Japan, and when the TD1-C model appeared in 1967, it had beautifully executed trench ports and pistons with holes. These rough-andready, kart-inspired extra transfers took the 35 horsepower of the B-model up to the 38 hp of the TD1-C. This was a new way of looking at two-stroke scavenging.

Two-stroke bike engines desperately needed new ideas because in 1968, the FIM banned the costly many-cylinders methodology of the 1960s with rules limiting 125s and 250s to just two cylinders and six speeds. Yamaha engineers rapidly explored multiple transfer ports. For their 1969 250 production-racer Twin TD2, they fed its secondary transfers from the crankcase through full-length ducts. The result was 44 hp and the first low-cost production racer with GP-level performance. Filling just two cylinders with kart-like multiple transfer ports would ultimately make both more and broader power than the V-Four zillion-rpm 1960s GP racers ever did. Two-strokes dominated GP racing for 25 years.

It’s upsetting when our cherished ideas are overthrown, but that jolts us out of our comfortable groove and restarts our thinking in a fresh direction. The result may be something better yet. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

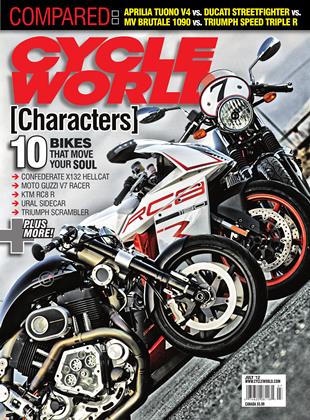

Up FrontCharacters In Exile

JULY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAvon 3d Ultra Radial Tires

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupNorton To Tackle Tt

JULY 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

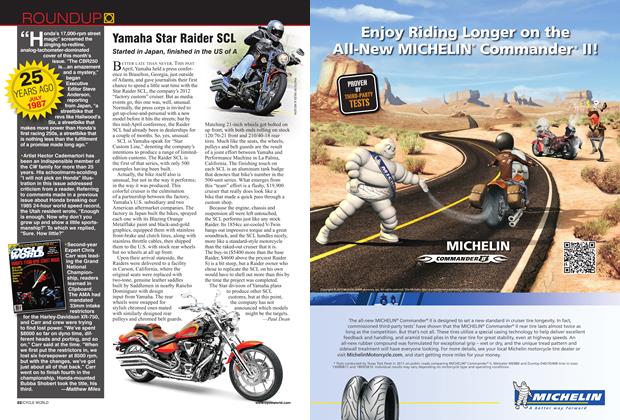

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1987

JULY 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Star Raider Scl

JULY 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Claudio Domenicali

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato