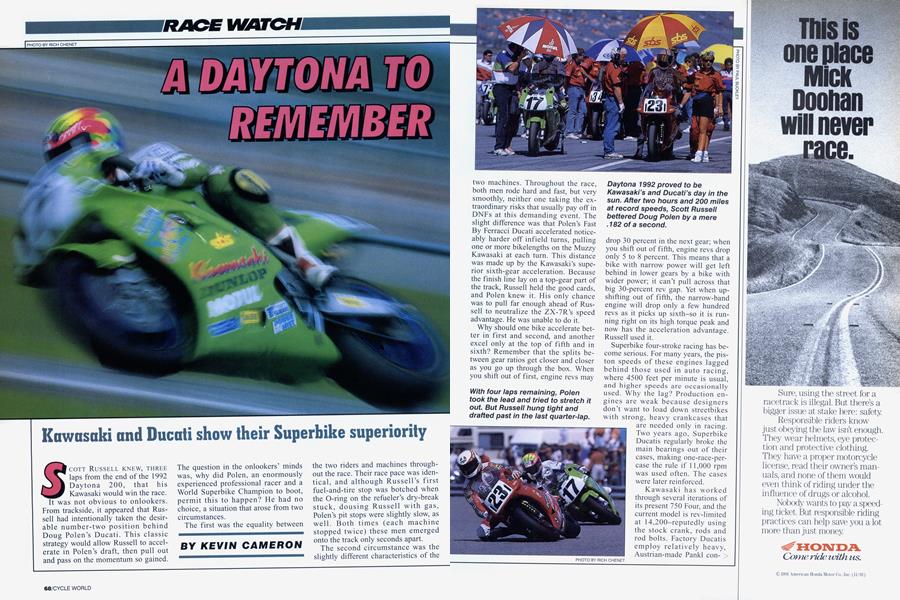

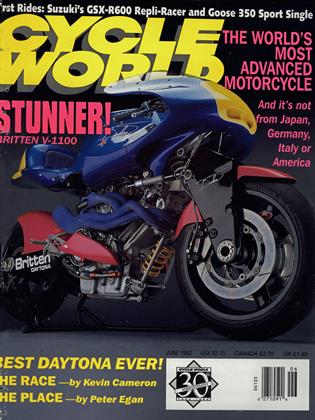

A DAYTONA TO REMEMBER

RACE WATCH

Kawasaki and Ducati show their Superbike superiority

SCOTT RUSSELL KNEW, THREE laps from the end of the 1992 Daytona 200, that his Kawasaki would win the race.

It was not obvious to onlookers. From trackside, it appeared that Russell had intentionally taken the desirable number-two position behind Doug Polen’s Ducati. This classic strategy would allow Russell to accelerate in Polen’s draft, then pull out and pass on the momentum so gained.

The question in the onlookers’ minds was, why did Polen, an enormously experienced professional racer and a World Superbike Champion to boot, permit this to happen? He had no choice, a situation that arose from two circumstances.

The first was the equality between the two riders and machines throughout the race. Their race pace was identical, and although Russell’s first fuel-and-tire stop was botched when the O-ring on the refueler’s dry-break stuck, dousing Russell with gas, Polen’s pit stops were slightly slow, as well. Both times (each machine stopped twice) these men emerged onto the track only seconds apart.

The second circumstance was the slightly different characteristics of the two machines. Throughout the race, both men rode hard and fast, but very smoothly, neither one taking the extraordinary risks that usually pay off in DNFs at this demanding event. The slight difference was that Polen’s Fast By Ferracci Ducati accelerated noticeably harder off infield turns, pulling one or more bikelengths on the Muzzy Kawasaki at each turn. This distance was made up by the Kawasaki’s superior sixth-gear acceleration. Because the finish line lay on a top-gear part of the track, Russell held the good cards, and Polen knew it. His only chance was to pull far enough ahead of Russell to neutralize the ZX-7R’s speed advantage. He was unable to do it.

KEVIN CAMERON

Why should one bike accelerate better in first and second, and another excel only at the top of fifth and in sixth? Remember that the splits between gear ratios get closer and closer as you go up through the box. When you shift out of first, engine revs may drop 30 percent in the next gear; when you shift out of fifth, engine revs drop only 5 to 8 percent. This means that a bike with narrow power will get left behind in lower gears by a bike with wider power; it can’t pull across that big 30-percent rev gap. Yet when upshifting out of fifth, the narrow-band engine will drop only a few hundred revs as it picks up sixth-so it is running right on its high torque peak and now has the acceleration advantage. Russell used it.

Superbike four-stroke racing has become serious. For many years, the piston speeds of these engines lagged behind those used in auto racing, where 4500 feet per minute is usual, and higher speeds are occasionally used. Why the lag? Production engines are weak because designers don’t want to load down streetbikes with strong, heavy crankcases that

are needed only in racing. Two years ago, Superbike Ducatis regularly broke the main bearings out of their cases, making one-race-percase the rule if 11,000 rpm was used often. The cases were later reinforced.

Kawasaki has worked through several iterations of its present 750 Four, and the current model is rev-limited at 14,200-reputedly using the stock crank, rods and rod bolts. Factory Ducatis employ relatively heavy, Austrian-made Pankl con> rods in steel. There have been occasional failures of the very heavily loaded rod bolts, for the Austrians don’t yet make use of the multi-phase steels pioneered by the U.S. firm SPS. Multi-phase steels not only have extremely high tensile strengths, but they also have high elongation before failure-they stretch before they break. This means it takes a lot of extra energy to break them. Eraldo Ferracci uses American-made steel Carrillo rods and bolts in the engines he builds for Doug Polen, and has never had a rod or a bolt fail-even in cases of piston break-up.

Polen turned a shocking 1:49 lap time in winter tire testing at Daytona, and in timed practice (the current form of qualification for the 200), he went 1:50.388, while Russell set second-fastest time at 1:50.743. Perhaps the fastest race lap was Polen’s lap 40, at 1:52.6. Race laps are expected to be slower than testing or qualifying laps because while race tires must go 20 laps (assuming a rear-tire change at each of the two gas stops), test or qualifying tires can be softer, grippier and shorter-lived. In any case, this leap forward by nearly 3 seconds in qualifying time is a measure of how fast Superbike performance is advancing.

Finishing third in the 200 was Commonwealth Flonda’s Mike Smith, on a Ray Plumbtuned RC30 Honda V-Four, with former 200 winner David Sadowski an amazing fourth on the formerly outclassed Yoshimura GSX-R750 Suzuki. Fifth was Canadian Steve Crevier on a Two Brothers Honda RC30. Japanese Kawasaki factory team rider Shoichi Tsukamoto, who had crashed spectacularly in practice in the fast infield left-hander, finished sixth after qualifying fourth behind teammate Takahiro Sohwa. Freddie Spencer, of whom so much is always expected, started far back after qualifying troubles, then was out with a wiped-out rear sprocket.

A crowd always forms in the tech garage as soon as the speed-trap results are posted there from Tuesday/ Wednesday practice-despite the fact that there have been years when these numbers were patently either mistaken (191 mph for Paul Smart’s Suzuki in 1974, for example), or “enhanced” for unknown reasons. This year, these numbers showed the factory Kawasaki rider, Sohwa, fastest at 178 mph, with Polen at 175 or so, and Russell at 174. Some controversy attends the rules, which limit four-cylinder bikes to 750cc and require a 363-pound weight minimum, while permitting Twins lOOOcc and a 309-pound minimum. Doug Polen’s 888 Ducati doesn’t fully inhabit the displacement allowance, but he reiterated this year that his big advantage is the ease of handling given by light weight. FIM officials, > murmuring about some possible unfairness in both a weight and displacement break for Twins, hied themselves to the last WSB round in Australia, only to see a very closely fought contest. The rules stand.

Friday’s 50-mile heats were rather ominously won by Polen and Pascal Picotte, both members of Ferracci’s Ducati team. But Russell had led his heat every lap but the last, on which a defective tire valve and resulting low tire put him back to third. Jamie James’ use of tire-warmers (perhaps a first in AMA racing) didn’t give his Vance & Hines Yamaha any visible first-lap advantage.

The new pecking order in AMA Superbike, as in World Superbike, is Ducati and Kawasaki, with everyone else second. The Ferracci Ducati of Doug Polen dominated the World Superbike title in 1991, and Kawasaki, in the process of being Ducati’s closest competition, came up with a 6horsepower gain. Polen didn’t race the U.S. series. Russell, who did, failed to win the title through inconsistency, despite clearly being the fastest rider on the AMA circuit.

Yamaha, which won the 200 not so long ago, and was second and third last year, could manage only a ninth at this year’s 200 (Larry Schwarzbach on the other Vance & Hines entry). Its seven-year-old design won the AMA title last season, with steady pointsgathering by Thomas Stevens (now on a Muzzy Kawasaki), and with improvements in chassis and combustion-chamber areas. The title win was more a matter of consistency than of speed, for the Kawasaki is definitely faster overall. Yamaha’s wide, thin, five-valve combustion chamber remains slower-burning than it needs to be, and produces little useful performance above 13,000. The Kawasaki’s chamber requires 20-25 percent less burn time, and is thus more efficient.

Suzuki, once dominant in AMA racing, fell to third-world status in the last two seasons, but had a minor renaissance at this Daytona. Two major problems for the GSX-R are a lack of powerband width and a need for improved cooling. Arrival of the new, liquid-cooled 750 next year may solve both problems, but for the moment, Yoshimura continues to show innovation in tackling the overheating dilemma. Last year’s bikes featured secondary oil radiators mounted above the rear wheel, and this year’s Daytona bikes had that, plus “extendo-fins” welded onto the cylinders’ stubby finning.

Since the AMA dropped its requirement of camshaft homologation, Honda has been able to run its more sophisticated “two-gear” V-Four motors (this refers to the number of gears between a cam and its drive pinion in the center of the crankshaft). Because of their stiffer cam drive, these can run more vigorous cam profiles without breaking anything. There is no end to the gadgetry that Honda has for these motors, and the teams admit to more than a little “pry-bar engineering”-the opening of boxes from Japan labeled, “Open this box if it won’t run under 1:52,” or “Open this if it won’t trip the clocks over 175.”

Naturally, nothing is simple. Kawasaki has paid dearly for its on-track performance, for to homologate its racing carburetor for World Superbike, it had to equip its ZX-7R streetbikes with this fuel system which, while it works superbly in racing, is an embarrassing handful in rush-hour traffic.

And now for the tangle of corporate politics: Imagine you are the chairman of a large manufacturer. In your ef> forts to win races worldwide, you have supplied your best technologies to your teams in the U.S. and Britain. Now those same teams come to your most important race, the Suzuka 8Hour, and they use those good parts to beat your home-based factory team. How do you look? How do you feel? Most importantly, what do you do about it? Why, of course, you throttle down the outflow of the latest stuff, and keep it for the home team. Then you set your PR spokesmen to making up whatever implausible explanations they think will be accepted abroad.

Being the creators of this technology in the first place, factories have every right to do this. This may make them look like aces at Suzuka, but they look rather less clever almost everywhere else in the world. And it causes the muttering and discontent clearly audible at Daytona.

Kawasaki has largely escaped this by putting Rob Muzzy under contract direct to Japan, thereby accepting him as a creative partner. This makes both the Japanese team bikes and Muzzy’s bikes faster. Ducati, equally as chauvinistic, has been forced to adopt a similar system, accepting Eraldo Ferracci and Doug Polen as the powerhouses they are, and coexisting with them. Naturally, this didn’t happen without some fairly dramatic (and unavailing) efforts to squeeze out Polen in favor of the factory’s own World Superbike rider, Raymond Roche. People usually compromise only when there is no alternative.

The two production giants, Yamaha and Honda, cling to the old political system in Superbike racing, and suffer as a result. And there is more-the brand-identification trap. Yamaha can’t give up its five-valve system because it has become the company symbol. Honda can’t adopt a modern, simple, inline CBR750RR for Superbike racing because the V-Four group at the factory is better at boardroom arm-wrestling than is the inline-Four group. Being fast is only one of the things it takes to win races.

This victory by Kawasaki is its first ever at the 200, overturning a “jinx” of 20 years’ standing. Kawasaki’s fourstroke technology is advancing faster than anyone else’s in motorcycling, and it shows. Ducati also proved a lot in finishing an eye-wink behind. Polen outqualified the field a year ago, then broke a chain. Bikes with big cylinders do that; when push-started, the first sneeze or two elongates the chain sideplates, which shortly fail. Now we know the machine can go the distance, at race-winning speed.

It was a great race. Maybe even the best 200 ever. □