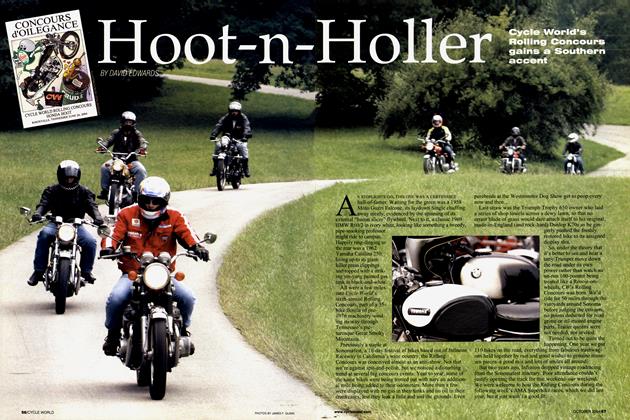

A MAN WHO QUIT school at age 13 designed the most influential, most-copied motorcycle chassis in history-and much else besides.

Irishman Rex McCandless devised the “Featherbed” frame for Norton’s use at the 1950 Isle of Man TT races. The year before, Norton’s famous Manx was an obsolete single-cylinder machine, falling behind in the new post-war world of Twins and Multis. But in 1950, with the McCandless chassis, Norton once again dominated the Isle of Man. The Featherbed continued as a major influence in motorcycle design for 30 years-in many ways, it still is.

The Featherbed is usually described as adding swingarm rear suspension and the rigidity of twin-loop construction to motorcycles badly in need of both. This is true, but it ignores the subtlety of McCandless’ engineering.

McCandless was born in 1915, on a north Ireland farm. His father, ruined by the Depression, left for greener pastures, and young Rex struggled with school, leaving in disgust at 13. Apprenticeships and jobs finally made him a truck mechanic, and he found his calling in machinery. An aunt’s gift of a small motorcycle gave this work a focus. A better job at Short Brothers, the Belfast aircraft builders, enabled him to buy a more up-to-date machine. He and brother Cromie then entered the business of servicing and modifying the heavy equipment then engaged in wartime airstrip construction.

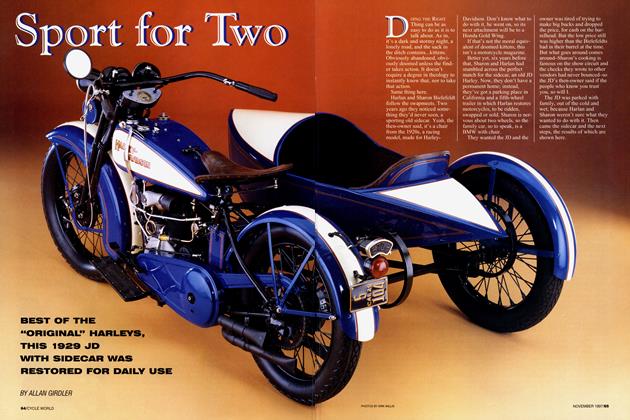

Now the owner of a new Triumph 500 Speed Twin, McCandless became a winner at Irish grass-track, hillclimb and roadracing events. Despite this success, he was critical of the Triumph’s handling. Bikes in 1940 had heavy tube-and-lug chassis; think of the technique as a sort of permanent metal Tinkertoy. Rear suspension was either nonexistent (rigid, as the Triumph was) or rudimentary (the sliding pillar suspension of the “Garden Gate” Norton racers). Rearwheel grip was terrible except on the smoothest surfaces. With the idea that more weight would keep the rear wheel in contact with the road, designers of the time set both engine and rider far to the rear. Rigid bikes hopped violently in rough going and were tiring-and eventually painful-to ride.

KEVIN CAMERON

Quitting School

Rex McCandless, father of the Featherbed

Many kinds of rear suspension had been tried on bikes, but all agreed that nothing steered as well as a rigid. McCandless rejected this, knowing that every car had rear suspension that worked just fine. He explored alternatives by constructing a special chassis for his Triumph. Twinloop construction was not new, but it answered McCandless’ need for a wide, well-braced base within which to pivot a rear “swinging arm.” He made his own telescopic hydraulic dampers from French Citroën car parts, combination, it so greatly improved rear grip that acceleration out of turns now made the bike’s front end too light to steer well. As an ad-hoc solution, he rotated the engine 45 degrees to bring the weight of its cylinder and head forward. It worked; the machine steered. This special Speed Twin, which McCandless nicknamed “Benial,” was so successful that he was besieged with orders for similar conversions.

He turned to carburetion, discovering that “megaphonitis”the narrow powerband caused by racing cams and megaphone exhaust-was partly the ill effects of engine vibration frothing the fuel in rigid-mounted floatbowls. To prove his points, McCandless once hung a doubter’s float from the frame with a shoelace; with the fuel isolated from vibration, performance improved amazingly. Today, all motorcycle fuel systems are vibration-isolated for the same reason.

As a tuner, he was asked in 1946 to wrench on Ernie Lyons’ promising new Triumph Twin roadracer. With its carburetion and ignition timing sorted out, this production-based machine carried Lyons to an upset win over Norton in the Manx GP. Wisely, Norton then asked McCandless to consult with them. He agreed, charging them £1 per hour (about $4, then) if his ideas worked, nothing if they didn’t. The ideas poured forth: new types of carburetors and floats, remotereservoir suspension units, smaller wheels, the Featherbed chassis, full streamlining, side-mounted fuel tanks, an exhaust-valve cooling system, a kneeling riding position and countless non-racing prototypes.

Once McCandless conceived an idea, he was committed to make it work. If others failed to see the matter as he did, so much the worse for them. From their first association in 1947, McCandless pressured Norton race boss Joe Craig to build a fourcylinder engine, knowing they’d soon need more power to counter the fast-developing Italian Fours.

In the interim, he’d make do with the Singles.

Improved handling he could deliver, and he retired to Belfast to do for Norton what he had done for his own Speed Twin. To push the engine as far forward as he wanted it, McCandless would need a smaller front tire (Honda gave its 1983 VF750 Interceptor sportbike a 16-inch front for the very same reason). At Norton’s request, Dunlop obliged. The new chassis was fillet-brazed using a low-temperature rod just coming into aircraft-industry use. Subsequently, such SIFbronze welding (for Suffolk Iron Foundry, the makers) would be the British special-builder’s method of choice until the coming of aluminum chassis. Twin loops braced the swingarm to engine and gearbox, and the steering head and horizontal upper frame rails were bolted to the cylinder head in three places. It was a rigid, economical structure. The tank, which had been a fracture-prone affair draped over a frame backbone, was now a simple box, supported on rubber by the two parallel top frame rails; countless factory racers from other makers would copy this straightforward construction for decades.

Norton, not entirely convinced, laid on a test session at the Isle of Man. Against the team’s Garden Gate Manx, the new bike could be accelerated confidently out of corners, even ridden right around the outside of the factory racer. It steered and it accelerated like never before. Next, they tried to break it with prolonged high speed at a French oval track, but its lugless, bronzewelded construction was durable. Geoff Duke gave the new bike its first competition outing at Blandford Camp-and won going away. At the commercially crucial TT, it was a 350cc and 500cc three-place sweep. Team rider Harold Daniell, asked if he was tired after his 220-mile ride, replied that he was well rested, having spent the day lying on a “featherbed.” The name stuck.

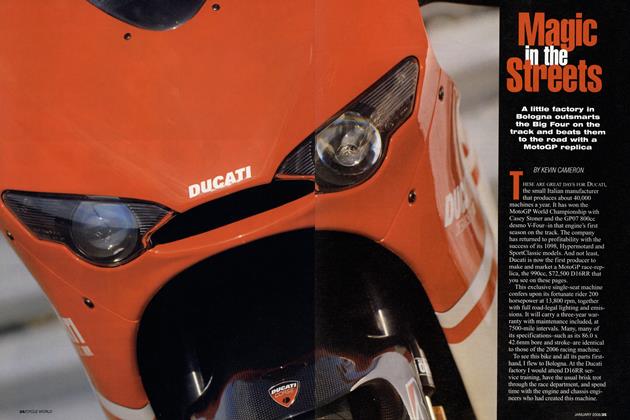

Handling provided, McCandless exploited what power the Singles had. With the Featherbed Manx already much lighter than previous machines, aerodynamics was the next point of attack. McCandless first reduced frontal area, lowering the rider by use of a cut-down frame and fiiel tank. As successive test builds lowered the rider more, his knees and elbows collided. McCandless therefore “unfolded” the rider to kneel over the bike, his knees in trough-shaped fuel tanks on either side, his feet pointing to the rear, his back horizontal. Fuel was lifted from the side-mounted pannier tanks to the carburetor by pump. Knowing that low drag requires not only small frontal area and smooth entry, but also closure of the flow behind the machine, McCandless provided a tapering tail enclosure-like those to come later on Italian machines. The result, nicknamed the “Kneeler,” was a radical, super-low, torpedo-like machine unlike anything seen before.

Meanwhile, Norton was failing as a business, being absorbed by Amalgamated Motor Cycles (AMC). Although the Kneeler, with its side-mounted tanks, extreme streamlining and standard Norton race engine, set 61 new world-speed records, development was stopped before its track potential could be evaluated. McCandless moved on to new things, while Norton fell back into the arms of tradition. The Kneeler concept, adopted into sidecar roadracing by the late Eric Oliver, lives on in that sport to this day.

Would the Norton Kneeler have worked as a solo? Some say no, that it didn’t handle properly even then. But the original Benial did not work first time out, nor did the first Featherbed prototypes. It was McCandless’ tireless, thoughtful development that made those machines work. Deprived of his guidance by AMC/Norton’s new insistence on a more conventional machine, the concept was killed before it could be pushed to maturity. The Kneeler remains a fascinating open question.

So ended a brilliant period in motorcycle development. McCandless, in his rational search for higher performance, had proposed ever-more radical solutions until those around him would no longer accept them. McCandless was a master of physical realities, but he had better things to do than stuff his good ideas through a resisting wall of human conservatism.

By all accounts, McCandless was a difficult man. Once he saw a solution to a problem, he saw it whole and expected others to do the same. Argument or discussion were not in him-you were for him or you were the enemy. His success with Norton and the turf-jealous Joe Craig may have owed more to isolation than to negotiation; Featherbed development was all done at the McCandless shop in Belfast, and on Irish roads. Friend and Norton team rider Artie Bell was principal tester.

McCandless went from the Norton experience to development of four-wheel-drive systems with the famous Freddie Dixon. For testing, he built two successful Formula Three racing cars with innovations such as inboard brakes, motorcycle controls and full streamlining. His “Mule” offroad vehicle, after defeating Jeeps, Land Rovers and assorted military all-terrain hardware in a special test, was eagerly sought by industrialist Harry Ferguson. Ferguson made the mistake of trying to buy McCandless. Irresistible force met immovable object; neither man ever made a dime from the Mule, which was never produced.

McCandless could walk away from Norton or from Ferguson because he had more than one good idea. He designed a system for firing brick kilns, cutting scrap rate practically to zero. He took up autogyro development despite well-publicized crashes and a British Airworthiness Board ban on their operation. Using a tethered prototype, he isolated the cause of the crashes, despite having no formal training in aerodynamics. He was 80 years old and still active when he died in 1992.

McCandless saw school as being not just valueless, but actively harmful, to creative engineering. Sour grapes? Not likely. Think about it: Traditional education is more about regurgitating Right Answers than it is about problem solving. Education does fill the student’s toolbox with math, history, physics-but offers little incentive to use them in original ways. What color is broccoli, Jimmy? Green? Good! And where does a motorcycle’s weight belong? On the rear wheel? Right again!

Wrong. McCandless wasn’t trying to win praise from a teacher with right answers. He was trying to make a motorcycle steer. Traditionalists tried to hook up the back wheel with weight, and failed. McCandless succeeded with a working combination of swingarm and hydraulic damping. When the resulting strong acceleration made the front wheel too light to steer, he moved both engine and rider forward until it did steer. Many test builds were necessary to produce the superb Manx Norton of 1950. Today, old-timers speak with reverence of British motorcycle handling, as though referring to something unknown and inaccessible, a lost chord, a dead art. Not so. Handling is for anyone who wants to create it, as McCandless did, by hard work and rational thought. The Manx may have been British, but its handling was from Belfast!

When Featherbed lookalike frames were tried on everything from Vincents to Japanese GP bikes, people were surprised when few of them handled like a Norton. The look of the Featherbed frame had been accepted as a Plight Answer, but no one understood exactly why it worked. And McCandless wasn’t there to put the bike/rider mass where it belonged. Honda’s ill-handling RC181 of 1967, Kawasaki’s bucking HIR and H2R of the early ’70s, Yamaha’s high-horsepower 250s from the late ’60s-bikes like these surely must have made McCandless chuckle. All had copycat Featherbed-style chassis, but not one of these machines would steer out of corners. All were unstable at speed. All had their weight misplaced.

Formally educated engineers, generously funded and equipped with the finest facilities, had accepted and used Right Answers instead of thinking for themselves. They missed the underlying principles that experience and thought had made clear to Rex McCandless, the man who quit school at age 13.

A collection of McCandless’ work can be seen at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in Northern Ireland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue