Vintage

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

WHAT IS “VINTAGE” IN MOTORCYcling? Aside from its formal meanings in collecting and in classic racing, it just means far enough removed from what is current to look archaic, strange—even slightly comic. A favorite reference book in my library is Velocette by Ivan Rhodes with a Mk. VII KTT 350cc Single on its cover. The rider is distinctly Darth Vader-ish in goggles and pudding-basin helmet, and his machine is clearly not of this world with its spindly girder fork, enormous front wheel and skinny tire.

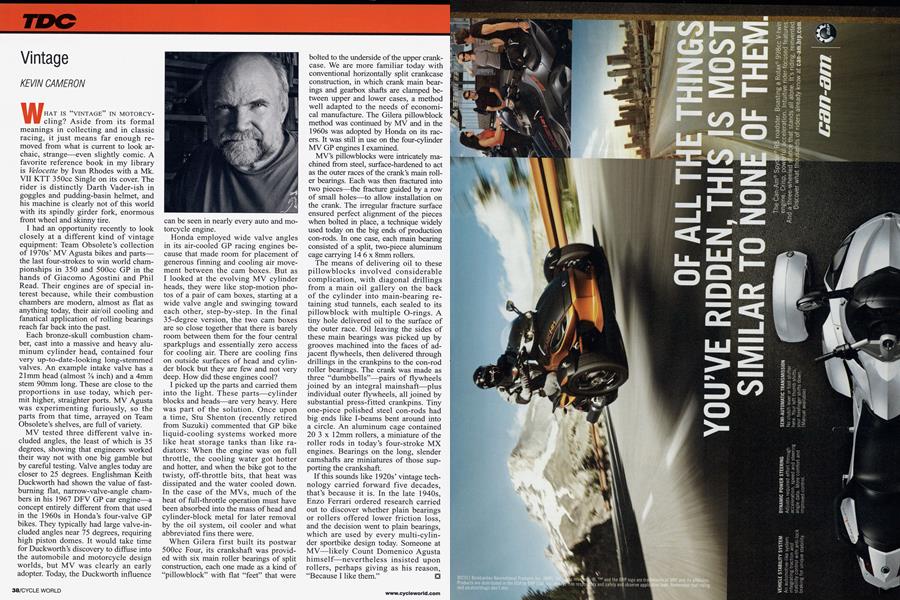

I had an opportunity recently to look closely at a different kind of vintage equipment: Team Obsolete’s collection of 1970s’ MV Agusta bikes and parts— the last four-strokes to win world championships in 350 and 500cc GP in the hands of Giacomo Agostini and Phil Read. Their engines are of special interest because, while their combustion chambers are modern, almost as flat as anything today, their air/oil cooling and fanatical application of rolling bearings reach far back into the past.

Each bronze-skull combustion chamber, cast into a massive and heavy aluminum cylinder head, contained four very up-to-date-looking long-stemmed valves. An example intake valve has a 21mm head (almost Vs inch) and a 4mm stem 90mm long. These are close to the proportions in use today, which permit higher, straighter ports. MV Agusta was experimenting furiously, so the parts from that time, arrayed on Team Obsolete’s shelves, are full of variety.

MV tested three different valve included angles, the least of which is 35 degrees, showing that engineers worked their way not with one big gamble but by careful testing. Valve angles today are closer to 25 degrees. Englishman Keith Duckworth had shown the value of fastburning flat, narrow-valve-angle chambers in his 1967 DFV GP car engine—a concept entirely different from that used in the 1960s in Honda’s four-valve GP bikes. They typically had large valve-included angles near 75 degrees, requiring high piston domes. It would take time for Duckworth’s discovery to diffuse into the automobile and motorcycle design worlds, but MV was clearly an early adopter. Today, the Duckworth influence

can be seen in nearly every auto and motorcycle engine.

Honda employed wide valve angles in its air-cooled GP racing engines because that made room for placement of generous finning and cooling air movement between the cam boxes. But as I looked at the evolving MV cylinder heads, they were like stop-motion photos of a pair of cam boxes, starting at a wide valve angle and swinging toward each other, step-by-step. In the final 3 5-degree version, the two cam boxes are so close together that there is barely room between them for the four central sparkplugs and essentially zero access for cooling air. There are cooling fins on outside surfaces of head and cylinder block but they are few and not very deep. How did these engines cool?

I picked up the parts and carried them into the light. These parts—cylinder blocks and heads—are very heavy. Here was part of the solution. Once upon a time, Stu Shenton (recently retired from Suzuki) commented that GP bike liquid-cooling systems worked more like heat storage tanks than like radiators: When the engine was on full throttle, the cooling water got hotter and hotter, and when the bike got to the twisty, off-throttle bits, that heat was dissipated and the water cooled down. In the case of the MVs, much of the heat of full-throttle operation must have been absorbed into the mass of head and cylinder-block metal for later removal by the oil system, oil cooler and what abbreviated fins there were.

When Gilera first built its postwar 500cc Four, its crankshaft was provided with six main roller bearings of split construction, each one made as a kind of “pillowblock” with flat “feet” that were

bolted to the underside of the upper crankcase. We are more familiar today with conventional horizontally split crankcase construction, in which crank main bearings and gearbox shafts are clamped between upper and lower cases, a method well adapted to the needs of economical manufacture. The Gilera pillowblock method was continued by MV and in the 1960s was adopted by Honda on its racers. It was still in use on the four-cylinder MV GP engines I examined.

MV’s pillowblocks were intricately machined from steel, surface-hardened to act as the outer races of the crank’s main roller bearings. Each was then fractured into two pieces—the fracture guided by a row of small holes—to allow installation on the crank. The irregular fracture surface ensured perfect alignment of the pieces when bolted in place, a technique widely used today on the big ends of production con-rods. In one case, each main bearing consisted of a split, two-piece aluminum cage carrying 14 6 x 8mm rollers.

The means of delivering oil to these pillowblocks involved considerable complication, with diagonal drillings from a main oil gallery on the back of the cylinder into main-bearing retaining stud tunnels, each sealed to its pillowblock with multiple O-rings. A tiny hole delivered oil to the surface of the outer race. Oil leaving the sides of these main bearings was picked up by grooves machined into the faces of adjacent flywheels, then delivered through drillings in the crankpins to the con-rod roller bearings. The crank was made as three “dumbbells”—pairs of flywheels joined by an integral mainshaft—plus individual outer flywheels, all joined by substantial press-fitted crankpins. Tiny one-piece polished steel con-rods had big ends like I-beams bent around into a circle. An aluminum cage contained 20 3 x 12mm rollers, a miniature of the roller rods in today’s four-stroke MX engines. Bearings on the long, slender camshafts are miniatures of those supporting the crankshaft.

If this sounds like 1920s’ vintage technology carried forward five decades, that’s because it is. In the late 1940s, Enzo Ferrari ordered research carried out to discover whether plain bearings or rollers offered lower friction loss, and the decision went to plain bearings, which are used by every multi-cylinder sportbike design today. Someone at MV—likely Count Domenico Agusta himself—nevertheless insisted upon rollers, perhaps giving as his reason, “Because I like them.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Mysteries of Grandpa

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupA Shift In Changing Gears

JULY 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBmw S600rr

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup“chrome” Hawk

JULY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupCycleworld.Com Poll Results

JULY 2011 -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1986

JULY 2011 By Blake Conner