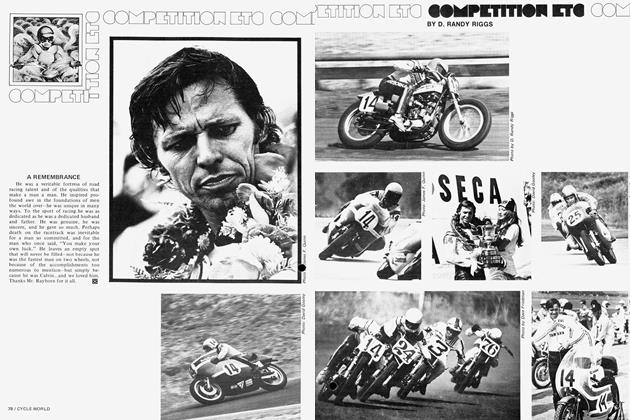

CALVIN LEE RAYBORN a story

D. Randy Riggs

IT WAS MORNING, and the new sun sparkled gold across the wet infield grass and heat waves danced and rippled off the surface of the track.

Some distance from the grandstands an engine was running, and the loudspeakers crackled that time trials soon would begin. A crowd of 50 racers came to dodge and fight for a position in the line. It was another busy race day beginning.

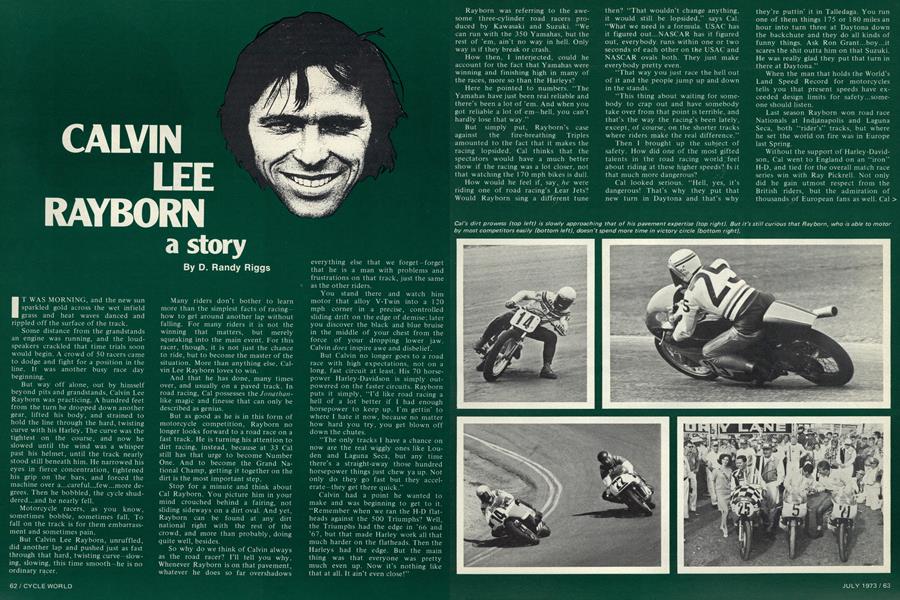

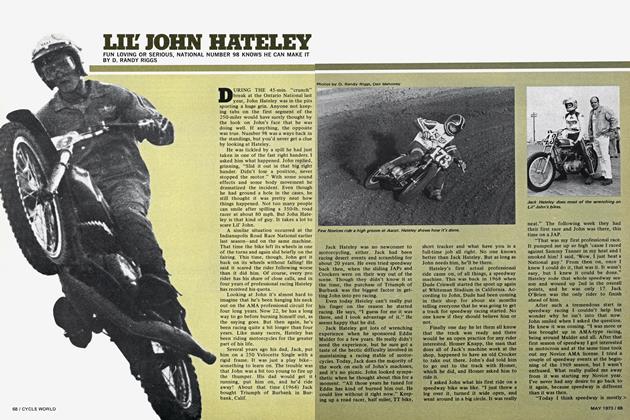

But way off alone, out by himself beyond pits and grandstands, Calvin Lee Rayborn was practicing. A hundred feet from the turn he dropped down another gear, lifted his body, and strained to hold the line through the hard, twisting curve with his Harley. The curve was the tightest on the course, and now he slowed until the wind was a whisper past his helmet, until the track nearly stood still beneath him. He narrowed his eyes in fierce concentration, tightened his grip on the bars, and forced the machine over a...careful...few...more degrees. Then he bobbled, the cycle shuddered...and he nearly fell.

Motorcycle racers, as you know, sometimes bobble, sometimes fall. To fall on the track is for them embarrassment and sometimes pain.

But Calvin Lee Rayborn, unruffled, did another lap and pushed just as fast through that hard, twisting curve—slowing, slowing, this time smooth—he is no ordinary racer.

Many riders don’t bother to learn more than the simplest facts of racinghow to get around another lap without falling. For many riders it is not the winning that matters, but merely squeaking into the main event. For this racer, though, it is not just the chance to ride, but to become the master of the situation. More than anything else, Calvin Lee Rayborn loves to win.

And that he has done, many times over, and usually on a paved track. In road racing, Cal possesses the Jonathanlike magic and finesse that can only be described as genius.

But as good as he is in this form of motorcycle competition, Rayborn no longer looks forward to a road race on a fast track. He is turning his attention to dirt racing, instead, because at 33 Cal still has that urge to become Number One. And to become the Grand National Champ, getting it together on the dirt is the most important step.

Stop for a minute and think about Cal Rayborn. You picture him in your mind crouched behind a fairing, not sliding sideways on a dirt oval. And yet, Rayborn can be found at any dirt national right with the rest of the crowd, and more than probably, doing quite well, besides.

So why do we think of Calvin always as the road racer? I’ll tell you why. Whenever Rayborn is on that pavement, whatever he does so far overshadows everything else that we forget-forget that he is a man with problems and frustrations on that track, just the same as the other riders.

You stand there and watch him motor that alloy V-Twin into a 120 mph corner in a precise, controlled sliding drift on the edge of demise; later you discover the black and blue bruise in the middle of your chest from the force of your dropping lower jaw. Calvin does inspire awe and disbelief.

But Calvin no longer goes to a road race with high expectations, not on a long, fast circuit at least. His 70 horsepower Harley-Davidson is simply outpowered on the faster circuits. Rayborn puts it simply, “I’d like road racing a hell of a lot better if I had enough horsepower to keep up. I'm gettin’ to where I hate it now, because no matter how hard you try, you get blown off down the chutes.

“The only tracks I have a chance on now are the real wiggly ones like Louden and Laguna Seca, but any time there’s a straight-away those hundred horsepower things just chew ya up. Not only do they go fast but they accelerate-they get there quick.”

Calvin had a point he wanted to make and was beginning to get to it. “Remember when we ran the H-D flatheads against the 500 Triumphs? Well, the Triumphs had the edge in ’66 and ’67, but that made Harley work all that much harder on the flatheads. Then the Harleys had the edge. But the main thing was that everyone was pretty much even up. Now it’s nothing like that at all. It ain’t even close!”

Rayborn was referring to the awesome three-cylinder road racers produced by Kawasaki and Suzuki. “We can run with the 350 Yamahas, but the rest of ’em, ain’t no way in hell. Only way is if they break or crash.

How then, I interjected, could he account for the fact that Yamahas were winning and finishing high in many of the races, more so than the Harleys?

Here he pointed to numbers. “The Yamahas have just been real reliable and there’s been a lot of ’em. And when you got reliable a lot of em-hell, you can’t hardly lose that way.”

But simply put, Rayborn’s case against the fire-breathing Triples amounted to the fact that it makes the racing lopsided. Cal thinks that the spectators would have a much better show if the racing was a lot closer, not that watching the 1 70 mph bikes is dull.

How would he feel if, say, he were riding one of road racing’s Lear Jets? Would Rayborn sing a different tune

then? “That wouldn’t change anything, it would still be lopsided,” says Cal. “What we need is a formula. USAC has it figured out...NASCAR has it figured out, everybody runs within one or two seconds of each other on the USAC and NASCAR ovals both. They just make everybody pretty even.

“That way you just race the hell out of it and the people jump up and down in the stands.

“This thing about waiting for somebody to crap out and have somebody take over from that point is terrible, and that’s the way the racing’s been lately, except, of course, on the shorter tracks where riders make the real difference.”

Then I brought up the subject of safety. How did one of the most gifted talents in the road racing world feel about riding at these higher speeds? Is it that much more dangerous?

Cal looked serious. “Hell, yes, it’s dangerous! That’s why they put that new turn in Daytona and that’s why

they’re puttin’ it in Talledaga. You run one of them things 175 or 180 miles an hour into turn three at Daytona down the backchute and they do all kinds of funny things. Ask Ron Grant...boy...it scares the shit outta him on that Suzuki. He was really glad they put that turn in there at Daytona.”

When the man that holds the World’s Land Speed Record for motorcycles tells you that present speeds have exceeded design limits for safety...someone should listen.

Last season Rayborn won road race Nationals at Indianapolis and Laguna Seca, both “rider’s” tracks, but where he set the world on fire was in Europe last Spring.

Without the support of Harley-Davidson, Cal went to England on an “iron” H-D, and tied for the overall match race series win with Ray Pickrell. Not only did he gain utmost respect from the British riders, but the admiration of thousands of European fans as well. Cal rates the experience as one of the high points of his career.

I wondered if those European riders were as tough as they were cracked up to be. He thought for a bit on that one. “It seems to me they’ve been overrating those World Champion guys.” Clarifying the point he says, “Now I don’t mean to say that they overrate their riding abilities...those guys are good. The thing is, hell...they’re not World Champions, they’re European Champions. They don’t even run here...there’s no World point race in America...so how can they call ’em World Champions?

“As much as I’d like to be Number One here, I’d like to go over there and run some of the GPs and go for some of their points, too, just to see what the hell would happen. I feel I can do just as good a job as those guys can.

“And don’t forget, we have six or eight guys here that can run with any of them...they can really get it on in road racing, and four of them can get it on in the dirt too. Those guys over there can only road race, they can't do anything else.”

Rayborn rates Pickreil and Jarno Saarinen as two of the toughest foreign riders, and would very much like to meet “Ago” head-to-head on equal equipment. That would be a race no fan would want to miss. Cal feels that Agostini would have it much tougher without his superior equipment. “After all, Cooper and others have beat him when they had just as much horsepower.”

One wonders where Rayborn picked up his fantastic pavement abilities. Maybe it dates back to his teenage days in

San Diego when he was “shaggin’ prints” (delivering blueprints) on his small bore street machine. Rayborn thinks that he might have racked up a “couple hundred thousand miles” after his high school days in four years of that first job.

After tangling with a few cars, Cal wasn’t so sure he liked street riding all that much. Turning to a few local races, he apparently attracted the eye of Leonard Andres, a Harley-Davidson dealer in San Diego. Andres’ son, Brad, had quite a hot shoe reputation himself during the 50s.

When Cal married his wife, Jackie, at the age of 19, supporting her was hard enough, much less worrying about spending money on racing. Cal kind of figures he would never have made it in racing without Andres help and support.

Riding a Gold Star Clubman as an Amateur at a Riverside Road Race in 1958, Cal crashed heavily and broke his back, his foot, and “a bunch of stuff.” He quit racing for a year and a half, but the bug was still there. Only this time around it was on the dirt only. “1 decided that pavement was too much...I wasn't goin’ for that anymore.”

Still under Andres sponsorship, Rayborn did a rethink on road racing and went to Daytona in 1965. His debut ended in a crash on the first lap when another rider fell right in front of him. The following year he gave a preview of what was to come as he set fast time and led for 16 laps before the engine expired.

His Daytona dream came true in 1968, and a year later he won it again, this time with a pin in his shoulder. But the injury didn’t occur on a race track.

Traveling from the Houston National with some other riders in a van, Rayborn caught some shut-eye in the bunk behind the front seats. A driver on the highway had stopped his car in the middle of the road late at night with no lights...the van plowed smack into the rear of it and tossed Cal right through the windshield.

Sound asleep, his first thought about his rude awakening was, “Hell, if they wanted to get rid of me they didn’t have to throw me out on the highway!” Luckily none of them were seriously hurt, but Rayborn was worried he wouldn’t be able to ride Daytona.

By this time Rayborn had established himself as a tremendous road racer, but had done little to fortify his reputation in the dirt, even though he finished third in National points in ’68. “Actually 1 liked the dirt better than the pavement to start with. That’s when we were riding the flatheads and they didn’t have that much steam. The rest of the guys on the Harley team were a lot smaller than I am, and that made a hell of a difference in the dirt. Just being lighter, they’d pull me two or three bike lengths off the corner.

“1 kinda thought...hell, this is no good...but I did really like the dirt. But then in road racing it didn’t seem like the weight made any difference, because they weren’t goin’ round the corner fast enough It seemed like I could blow them off real good with the flathead... and you get to where...Goddamn, you really like that, see...and then you really concentrate on that particular thing. I just put a lot of effort into it and decided that if that’s the thing I can do, then that’s what I’m gonna do.”

This kind of attitude paid off, and as the “go fast” man on the Harley team, Cal was approached by team manager Dick O’Brien to ride...drive...or point the Harley streamliner to a world record in 1970.

“Dick came up to me at Ascot one night, and asked me if I wanted to run a streamliner. That was a bad year for the Harley team and 1 didn’t make any money at all, so I needed the money and l said, kOK, we’ll do it.’

“Boy, I didn’t know what I was lettin’ myself in for. That was the most scary thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

Cal experienced several roll overs and spills during the attempts, the worst of which was when “it did about 35 rolls like a cigar. But it all turned out OK.” That it did. The 265.492 mph record still stands today.

Rayborn nearly turned to car racing at one time, a thought he still entertains. The reason is money. Only recently has motorcycle racing shown an improvement in this respect, but the auto races still pay the big purses. Cal now owns a Lola Formula A car which he is selling, simply because he has no time for both that and motorcycle racing.

When he and Harley-Davidson teammate Mert Lawwill got the car racing bug a few years back, they bought a Trans Am Camaro. But they, too, were caught in the middle. Neither could give up the bikes long enough to do anything with the car.

Rayborn feels that racing a car doesn’t have quite the thrill of hanging it all out on two wheels, but he wouldn’t want to give either up. “Both have their exciting points,” he adds.

Cal has done well by motorcycle racing, but he would like to do better still. “It’s kinda hard to give up the good things once you’re use to them.” He obviously wants no part of going

back to being an automobile mechanic. If auto racing looks like a better future prospect for Cal, then that’s where we could expect to find him. Unfortunately, auto racing’s gain would be motorcycling’s loss.

Just one look at Calvin’s key chain would be a good indication of his life style these days. When he isn’t racing, he might be found toying with his LT-1 Corvette, or slamming across a Southern California desert on his 400cc play bike. He heads for the races in either a van or a fully equipped motor home, depending on whether or not his family goes along. His home is plush, but not excessively so...just enough to be comfortable.

Cal crashed heavily at Daytona this year, breaking a couple of ribs and his collarbone. This forced him to pass up the Dallas Road Race National, where he felt H-D had a good chance, and he’ll go to England for the match race series in less than the best of shape.

No matter, Cal is just as pumped as ever about the prospects of returning to Europe. And this time the Harley-Davidson factory is behind him all the way, and he’ll ride the more reliable and faster alloy racer, instead of the iron beast he rode last year.

He feels the biggest competition will come from “those hundred horsepower things,” but it doesn’t bother him. Rayborn will try that much harder and look that much better when all the odds are against him. Watch him some time. Calvin Lee Rayborn flies higher...just like Jonathan....