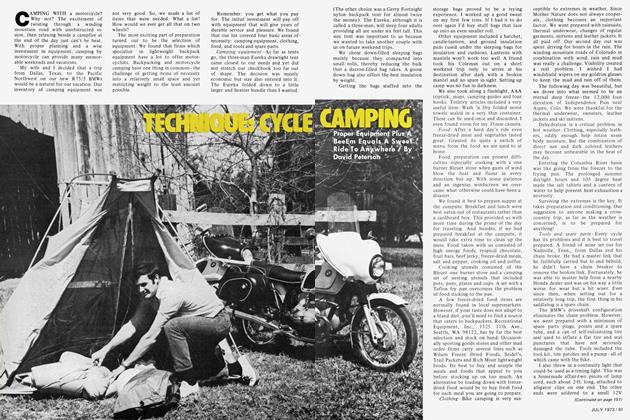

"FEEDBACK"

MOTO GUZZI AMBASSADOR

One year and 8177 miles have passed since this 38-year-old writer purchased his Moto Guzzi 750 Ambassador.

The bike was purchased new from a local dealer, who was unable to stipulate the exact warranty period for the 750. He merely indicated “you’ll get something in the mail from the distributor. Several months later, I wrote to the distributor, Premier Motor Corporation, for specific warranty data. A reply from the firm’s advertising and public relations manager promised that I would be sent a warranty and registration card from Italy. To date, I have yet to receive any warranty data.

Meanwhile, after two weeks of initial driving the light switch dimmer shorted out and required mail order replacement (no charge by the dealer).

The headlight bulb burned out, followed by the taillight bulb. The plastic generator cover then vibrated loudly because of several cracks in the mounting holes. This cover, I might add, has been ordered since last September. Despite several letters to Premier Motors, we have not been able to purchase a replacement. The stoplight switch assembly on the hand brake had shorted out, causing a puff of blue smoke while in the midst of a stop.

The clutch assembly has now developed a “knocking” sound while in neutral. Two local dealers were unable to prescribe a solution, except to speculate “it’s a throwout bearing—we’ll have to order one for you.” After 3500 miles the front tire began to “bounce” at any speed above 70 mph. Changes in fork oil viscosity, tire pressure and balancing have failed to remedy this problem.

At 5000 miles the speedometer cable broke—another item required to be mail ordered. The front brakes, in spite of frequent adjustment, “screech” whenever applied.

When operated for several hours at turnpike speeds, the engine and drive shaft assembly will ultimately reveal oil stains along housings and seams—much more obvious than on previously owned Japanese bikes.

With respect to the more favorable reports on my 750 Guzzi, I am pleased with the comfort of the saddle and the overall engine performance. But when it approaches time for a part or specific correspondence from the distributor, it leaves much to be desired. It would appear that my trade-in of a 450 Honda for the Guzzi was ill-advised in my quest for reliability and craftsmanship!

Joseph Pokrandt Cleveland, Ohio

“NOTHIN’ LIKE A 40-INCHER”

I own a ’67 TR-6C, bought new in March of ’68. I was living in Colorado at the time and I purchased this machine as my answer to the all-in-one motorcycle problem. It has performed all the riding styles there are, not necessarily fastest or best, but accomplished them one way or another.

After one trail ride I replaced my stock gearing with Triumph’s wide ratio gears—thereby maintaining a stock 4th gear for speed and gaining low gears for slow going hills. These have worked without flaw ever since. They do eliminate drag racing, though, the gap between 3rd and 4th being very large indeed.

My Lucas horn fell off right away and vibration destroyed two speedometers before I gave up replacing them. Since 10,000 miles or so I have had neither.

After 12,000 miles of standard Triumph operation, that is to say a certain amount of leaking, crash damage and tire and chain replacement, I hauled it to Alaska, where I promptly holed a piston because I failed to change to sea level jets. The Triumph shop in Anchorage had a piston, which I installed right off.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 28

Returned to Colorado and decided to do a top end, at roughly 14,000 miles it was due. When the top was off the engine I saw that my cams were shot too, so I did the whole number and got some “wearproof’ TT cams.

Right after the engine was broken in again I got a combination failure, way out in a Utah desert. I lost half my starter, and while overstressing the hell outta the left cylinder to get back the primary chain tensioner broke and locked everything solid from parts jamming sprockets, no bed of roses that. A fellow with a jeep towed me out.

When repairing that mess I discovered the exhaust TT cam was worn out too! This made in the USA trick cam was wiped out in 1000 miles. I replaced it with the stock item.

I rode this combination for another year, along the way, replacing all the fork bushings and seals, which I made myself (being a machinist comes in handy when you own a British motorcycle).

Next I decided I needed more horsepower, so I got a Bonneville head, a set of 10.5:1 pistons, “R” lifters and made up adaptors to hang a set of 28mm Mikunis on the manifolds. It took some time to straighten out my tuning because I’d moved to Reno and was doing altitude changing in rides over to California. Finally I hit a slightly rich mix in Reno that didn’t get too lean in San Francisco and am satisfied. (

Then I was toasting up Mt. Hamilton, some 20 miles from Santa Clara, and the small end of the left rod blew off. I figured the bushing moved inside the rod, cut off the oil supply and things hammered themselves to flinders in just a few seconds.

When rebuilding the engine I went back to stock parts. Standard pistons (0.040 over) standard lifters and replaced the intake TT cam as too worn to carry on. Naturally I put in new inserts, too, but other than the trash embedded in them from the blow up they were in fine shape, good for another (estimated) 25,000 miles. After putting it on the street again I could note very little performance change, perhaps more power at low rpm if anything—so much for those 10.5:1 pistons. Others say you never get power from high compression with two stock pipes. Anyway, my 40-incher once again runs strong and clean up here in Seattle.

(continued on page 36)

I `~/ `.~.` L_~' L Continued from page 32

By this time my old high-pipe 650 is somewhat banged up, rusty from Mexican bench riding and missing all parts not required by law and common sense. Long gone are the tank name plates, for example, and every now and then some fellow riding on a Honda 350 comes up and asks, “what kinda cycle is that?” Much to my dismay. My motto is “Fortys Forever” or “There ain’t nothin’ like a Forty,” because with all the times I’ve fixed my 40 it has delivered so many hours of fine riding through all conditions, so many faultless starts when going to work that a certain amount of wrench bending is small stuff. All you have to do is add a little oil to the primary case every now and then, two prods with the starter and the Forty lights up for another day’s ride to anywhere. For a true all-in-one machine there is no better.

Forest Asmus

Seattle, Wash.

WELL-MANNERED SUZUKI 380

I purchased a new ’72 Suzuki GT 380 J in August 1972. I have owned several dual-purpose bikes, but this has been my first street bike. It currently has 12,000 miles on it and I appreciate it more every day for its dependable and well-mannered ways.

The 380 is without a doubt slower than most middleweight two-cylinder two-strokes, but has never failed to put down any 350 Hondas on acceleration or top end. It will cruise all day at 70-80 mph, without complaining. Around town performance is quite tractable, with the six-speed transmission always offering the proper ratio for just about any task. Although I have never had the bike at the strip, I would estimate an e.t. in the low 15s or high 14s. Top speed is an indicated 98 mph. It’s not a screamer, but it’s not exactly a slouch, either.

As far as handling is concerned, the front suspension could use more travel, as I have bottomed it out on several occasions. The 380 is an excellent around town bike as it’s easy to manhandle at very slow speeds. High speed cornering is limited by the centerstand and tires, but is acceptable with the rear shocks at their stiffest setting, for all but the most demanding situations. Braking is just barely adequate, provided you have a good imagination. The front drum is just not up to more than one high speed stop without cooling. The original front wheel assembly was replaced at 100 miles by the dealer, after I complained of severe vibration during braking at 40 mph and above. The original drum was cast off center and was replaced by the dealer at nc cost, even though this item was not covered by Suzuki’s excellent warranty.

(Continued on page 38)

Continued from page 36

The 380’s reliability has been superb. Starting is always a one-kick operation, even after being in storage for over two months! The prescribed warranty maintenance has been performed at the required 2000-mile intervals and at some $30-odd a shot one wonders if the warranty is worth the extra $150 for maintenance that could be performed by most serious enthusiasts. At any rate the service provided by the dealer has been first rate and deserves credit. The only parts replaced in 12,000 miles have been spark plugs at 2500-mile intervals. I have also changed to a colder plug for touring. I have had very good luck with AC 42 XLs, and they are quite a bit cheaper than the Japanese plugs.

The 380 is a very comfortable and forgiving bike. I have traveled 600 miles a day without becoming sore or uncomfortable. I have installed a Bates fairing, which lowers top speed by 10 mph but offers much comfort and protection in exchange for a little speed and fuel. The only changes and improvements I would like to see are minor and in some cases have been rectified on the ’72s. The bike definitely needs better brakes, rear shocks, and more front suspension travel. Also, I would like to see Suzuki adopt the sealed beam headlight as on the 550s and 750s. The gearing in top gear could stand to be slightly taller for better gas mileage and reduced engine wear, but this is strictly an individual gripe. The most impressive features of the 380 are its vibrationless and very quiet operation, not to mention its reliability, all of which make it one of the few middleweights aptly suited to “Take on the country.”

Lee K. Shuster Andrews AFB, Md.

'69 EAGLE (LAVERDA) 750

Mr. Hopkin’s Kawasaki-Laverda comparison has prompted me to write about my Laverda. I bought my EX American Eagle in July of 1971 with 2000 miles on it. Now it has 7500 miles, its second set of points and third set of plugs.

I have replaced the original seat, which was ripped, installed Dunstall megaphones, drag (low) bars, K-81s front and rear, and replaced the 2LS front brake with a 4LS.

Problems, sure-the battery went dead and was replaced, the tach broke, and last month the springs in the electric starter failed. I have just received the parts and will install them soon.

Performance isn’t shattering or embarrassing. I don’t street drag, butj like to play road racer on the country roads in back of Richmond. I don’t meet a lot of other bikes, but so far only Norton and BMW have beaten me. It takes a lot of effort and muscle to force it through a tight turn, as it’s not a 350 two-stroke.

(Continued on page 40)

Continued from page 38

The bike was designed for high-speed touring and it really comes into its own on the interstate. The low bars are awkward in town, but once you get above 60 mph the wind lifts your weight off your wrists and you “float.” You don’t grip the bars, just rest your hands on them. What little vibration there is doesn’t get through the rubber grips.

In March of last year I rode to New Jersey, about an 8-hour trip by car. I covered 400 miles in 5-1/2 hours. I have a 5-gal. tank and get about 45 miles to a gallon on the road.

Between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore I cruised at 95 mph indicated, 6000 rpm on the tach, for one solid hour. This one hour sold me on Laverda. Rock steady is the only way to describe the bike’s handling. It really inspired confidence in me. It didn’t hunt, wiggle or feel hinged in the middle, just gracefully arced through curves and never missed a beat. The engine stayed oil tight and didn’t require any attention whatsoever; nor did any type of wind blow me around.

I am definitely satisfied with my Laverda. I’ve yet to see another one and therefore feel unique to have the only one around. The motorcycle really grows on you, as nothing has been spared to make it the best.

Even that funny key-in-the-headlight says class! You push it in, close the choke, and touch the starter. It’s like you turn the engine on the instant you touch that button. No grinding or complaints—the engine just bursts into life.

So before you buy that Multi, think of that extra carb you have to fiddle with; the extra point that has to be adjusted. Complex or more isn’t necessarily better.

By the way we still wave to each other out here in Richmond.

Russ Jennings Richmond, Virg.

1972 YAMAHA XS2

After about three months and 5000 miles of ownership, my 1972 XS2 has earned several compliments and a few “wildly emotional” but well-founded invectives.

Performance is good. The Yamaha is the most vibration-free vertical fourstroke Twin I’ve riden. It has been slightly faster than several Triumph Bonnevilles and much slower than a Honda 750 Four. And, the capabilities of moving quickly and smoothly are further enhanced by fantastic braking power. The new front disc earns Yamaha 10 points!

(Continued on page 42)

Continued from page 40

I can’t fault reliability so far, as I’m still on the original set of plugs and haven’t had to set the valves or timing for 3600 miles. Of course, the chain is a typical Japanese rubber band; but surprisingly, though it’s stretched farther than a Master-Charge Card at Macy’s, it’s still within usable tolerances with zero sprocket wear in evidence. The electric starter, which is of rather unique design (being combined with a “decompressor”), hasn’t failed me yet; but if it does, I’ve found the bike will always start the first or second kick on the lever.

I haven’t needed much in the way of parts or service, but little things like nuts and bolts or valve-cover gaskets have been on order for quite awhile... wonder what happens if something big goes wrong?

Now the invectives: As I was merrily chasing down the road—wide open where possible—checking out the whole thing, I came across some beautiful curves. Riding Walter Mitty-cum-Gary Nixon fashion, over to the pegs I went. The otherwise beautiful Yamaha then turned to absolute beast! I’ll swear that Yamaha has hidden two large hinges in the frame under the seat! Several tries at air pressure changes, fork oil changes and various length spacers in the forks have resulted in improvements (the final setup being stock air pressure, a stock amount of 40W oil in the front forks and 5/8-in. spacers in addition to the stock items already there. Don’t forget to go to the hardest position on the rear shock absorbers. This major flaw is not ever noticed at normal touring speeds, but my advice is don’t push it. I think I’ll sell mine and go back to Guzzi, or maybe try a Honda Four, or if Yamaha cures the cornering “gollywobbles,” maybe they’ll have a nice 750.

Les Baird Juneau, Alaska

1970 TRIUMPH 650

Regarding B.A. Szabo’s letter in Feedback (Sept. ’72), I expect that Mr. Szabo is well on his way toward trading his motorcycle for a Cadillac. Isn’t that the logical end to his manner of thinking?

I rode a 1970 TR6R 20,000 miles without benefit of fairing and all of my bones remain intact. I now own a 1972 TR6R which some readers might be interested in. The machine is one of several European versions which supposedly entered this country by mistake. I truthfully don’t know how it got here but I would be interested in knowing. The outstanding differences are a 5-gal. tank, a long front fender, much quieter exhaust and lower, more narrow bars which I replaced with Flanders 22-in. flat bars. The larger tank is a boon when touring, the quiet exhaust is a joy to myself and my neighbors, and the flat bars lend themselves to the contours of the bike and aid in the handling department during jaunts through the nearby Rocky Mountains.

(Continued on page 46)

Continued from page 42

The machine now has 6000 miles on it and the following deficiencies are noted—one headlamp bulb, two signal bulbs, new speedometer at 1552 miles and replacement of rear wheel bearings which were faulty. All of these repairs were handled under warranty by Bill Brokaw Motorcycles in Colorado Springs. There was no such fuss as I have heard about from other people concerning other shops. The necessary repairs and adjustments were made immediately. This is one dealership where everyone involved is a motorcyclist first and a businessman second, which is a situation rapidly disappearing from the scene. Too many times I have walked into a shop and been greeted by a high-pressure salesman.

Mr. Szabo might be interested in knowing that I recently rode 540 miles straight through at speeds constantly in excess of 70 mph. The next day I turned around and rode straight back in the same manner. Yes! Really! On “the world’s worst vibrator!” On the one hand I have known individuals who couldn’t ride more than 50 miles in one whack on a magic carpet and on the other I have known people who would ride more than 400 miles per day on a Honda 175. I think the amount of true enthusiasm found in each motorcyclist is the common denominator.

I’d like to throw in a few suggestions and do a little bragging about my Triumph right now. When buying a new Triumph, or any bike for that matter, watch all the nuts and bolts, etc., very carefully during the break-in period. If one decides to wiggle loose, use LocTite on it and it won’t come loose when it’s not expected. Don’t throw any loose items such as tools under the seat in the shelf provided. Too many important electrics are under there now and a screwdriver across the wrong terminals can cause costly damage. I always carry a small bag on the bike for my rain suit, tools, gloves, etc. And for my last word of unrestrained bragging—this bike has not leaked even one little drop of oil since the day it was assembled.

(Continued on page 48)

Continued from page 46

Jerry L. Hall Colorado Springs, Colo.

JOHNSON SPEAKS OUT!

Inasmuch as the letter I sent your Feedback column (published in the Sept. ’71 issue) concerning the experiment with six different motorcycles has evoked considerable comment, I feel obliged to clarify certain aspects of it for your readers’ benefit, especially Messrs. Dilley, (Jan. ’72) and Culver, (June ’72).

Mr. Dilley implies that our opinion of the H-D Electraglide was unjustly critical insofar as it is inconsistent with his own. Although we are aware that differences exist in mass-produced products, it is noteworthy that our H-D rider owned two brand-new Electraglides at that time and we reported on the one that performed the best. Mr. Dilley avers that the Electraglides’s controlability is “absolute duck soup” over 10 mph. We don’t know whether we share this view or not, but we were tickled by his most significant choice of metaphor. He does mention “an extremely slight vibration” at 75-85 mph and attests to 750 miles in one day, but we noticed that he very carefully dimensioned his own masculinity in this connection while serving to question ours. He may rest assured that we are all able-bodied men, considering our ages are woefully close to his own.

All kidding aside, Mr. Dilley, the Electraglide is all you said it was; a big, powerful, durable tourer. Our comments were not meant to demean it in any way. Some of the criticisms we mentioned were no doubt peculiar to the motorcycle under scrutiny at the time and, as you said, are not necessarily representative of the marque. The subjective criticisms, i.e. those on vibration, clumsiness and braking, were a direct result of comparison to the other cycles which, while they were superior in these areas, yeilded nowhere near the comfort of the H-D. I must add that we found your rear tire mileage astonishing for the road speeds you mentioned.

I would like to assure Mr. Culver that every word of our commentary is true, and remind him that the speed limits in Illinois and Iowa, for example, are 70 and 75 mph respectively and safety alone compels us to travel at or slightly above these speeds to avoid any great differential with other traffic. On or near the bypasses around such large complexes as Chicago or Indianapolis even greater speeds are often necessary. These high-speed conditions have enabled us to discover the disadvantages of soft-compound tires, such as the Metzler or Continental, and 15-tooth countershaft sprockets, such as those found on Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha. Why the Japanese persist in using these small sprockets is baffling to us, since they appear to be a primary cause of chain wear. We don’t feel that endless chain will solve this problem, either, it will only complicate the inevitable replacement.

(Continued on page 50)

Continued from page 48

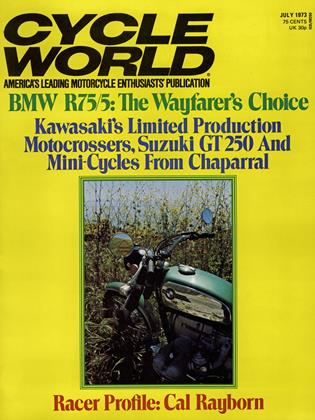

Mr. Culver asks if the BMW rider speeds down the highway with us feeling all the while as if he is on the verge of a wobble. All my R75 friends assure me that they do indeed feel this way. After exaustive experimentation we found one solution to be the framemounted Avon fairing, with spacers in the fork to compensate for the added weight. Another solution is to ride with no shield at all. A third is to mount anything you want on the bars and ride very slow. This is also true of the ’72 models.

We were interested to learn of the abrasive qualities of New York and Pennsylvania highways as indicated by your surprisingly short tire life. We hope you never fall on such a surface. We admit we don’t know what your state inspection practices are, but we generally get around 10,000 miles out of a soft-compound rear tire. The exceptions are the Moto Guzzi, which gets about 8000, and the BMW 12,000 on the one you wondered about. Harder compounds, such as the Dunlop K70, are capable of considerably more.

Alan R. Johnson Rock Island, 111.

KITS AND FASTENERS

I have owned maybe a dozen bikes, including the two I have now, and I have never seen a sensibly designed or mounted tool kit. Usually the kits are hard to remove, harder to replace, and just about big enough to carry two small cigars, lying side-by-side. My ’69 TR6 is a case in point; the tool kit is held in place by a couple of prongs and a bolt with a big, fat plastic head that screws into a tiny square nut held loosely by a spring clamp. It is very easy to crossthread the bolt onto the nut, and that is the end of the bolt’s useful life. If you are riding along, and you hear a sort of musical, tinkling sound behind you, it is time to stop and retrieve your tool Kit.

I have found that the easiest way to deal with these abortions is to do a little cutting and welding, and enlarge them to the point that you can carry some decent tools without spending 30 minutes packing them into place. On the Triumph, it’s no problem at all to triple the size of the tool kit without making any visible external change.

As for mounting the kit, there is a very handy little device called a Dzus fastener (pronounced Zoose), which is widely used on aircraft. (I realize you and some of your readers already know about this, but some don’t.) A Dzus fastener is very small and simple, opens and closes with a quarter turn of a wingnut and, when closed, is kept shut by spring tension. It cannot be loosened by wind or vibration, hence the aircraft applications.

Dzus fasteners are also useful for keeping other removable parts and covers in place, such as battery covers, flip-top seats, etc.

Any shop that services aircraft can provide you with a handful of Dzus fasteners in various sizes. I can’t tell you how much they cost, because the local Piper and Cessna dealers have never charged me anything for them.

Len Duerbeck Anchorage, Alaska

View Full Issue

View Full Issue