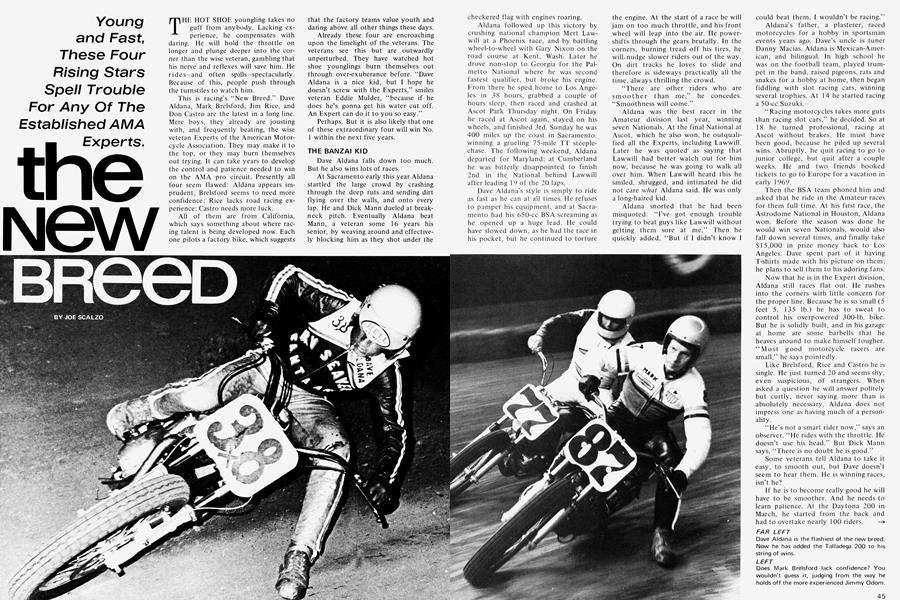

THE NEW BREED

Young and Fast, These Four Rising Stars Spell Trouble For Any Of The Established AMA Experts.

JOE SCALZO

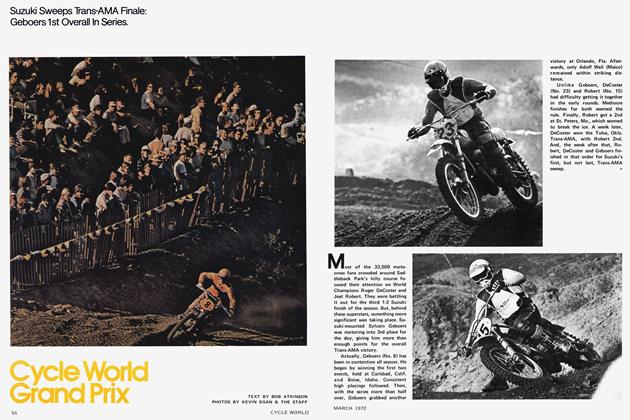

THE HOT SHOE youngling takes no guff from anybody. Lacking experience, he compensates with daring. He will hold the throttle on longer and plunge deeper into the corner than the wise veteran, gambling that his nerve and reflexes will save him. He rides—and often spills—spectacularly. Because of this, people push through the turnstiles to watch him.

This is racing’s “New Breed.” Dave Aldana, Mark Breisford, Jim Rice, and Don Castro are the latest in a long line. Mere boys, they already are jousting with, and frequently beating, the wise veteran Experts of the American Motorcycle Association. They may make it to the top, or they may burn themselves out trying. It can take years to develop the control and patience needed to win on the AMA pro circuit. Presently all four seem flawed: Aldana appears imprudent; Brelsford seems to need more confidence; Rice lacks road racing experience; Castro needs more luck.

All of them are from California, which says something about where racing talent is being developed now. Each one pilots a factory bike, which suggests that the factory teams value youth and daring above all other things these days.

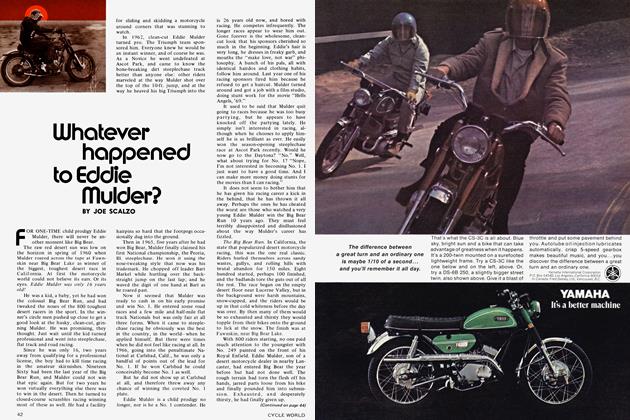

Already these four are encroaching upon the limelight of the veterans. The veterans see this but are outwardly unperturbed. They have watched hot shoe younglings burn themselves out through over-exuberance before. “Dave Aldana is a nice kid, but I hope he doesn’t screw with the Experts,” smiles veteran Eddie Mulder, “because if he does he’s gonna get his water cut off. An Expert can do it to you so easy.”

Perhaps. But it is also likely that one of these extraordinary four will win No. 1 within the next five years.

THE BANZAI KID

Dave Aldana falls down too much. But he also wins lots of races.

At Sacramento early this year Aldana startled the large crowd by crashing through the deep ruts and sending dirt flying over the walls, and onto every lap. He and Dick Mann dueled at breakneck pitch. Eventually Aldana beat Mann, a veteran some 16 years his senior, by weaving around and effectively blocking him as they shot under the checkered flag with engines roaring.

Aldana followed up this victory by crushing national champion Mert Lawwill at a Phoenix race, and by battling wheel-to-wheel with Gary Nixon on the road course at Kent, Wash. Later he drove non-stop to Georgia for the Palmetto National where he was second fastest qualifier, but broke his engine. From there he sped home to Los Angeles in 38 hours, grabbed a couple of hours sleep, then raced and crashed at Ascot Park Thursday night. On Friday he raced at Ascot again, stayed on his wheels, and finished 3rd. Sunday he was 400 miles up the coast in Sacramento, winning a grueling 75-mile TT steeplechase. The following weekend, Aldana departed for Maryland; at Cumberland he was bitterly disappointed to finish 2nd in the National behind Lawwill after leading 19 of the 20 laps.

Dave Aldana’s style is simply to ride as fast as he can at all times. He refuses to pamper his equipment, and at Sacramento had his 650-cc BSA screaming as he opened up a huge lead. He could have slowed down, as he had the race in his pocket, but he continued to torture the engine. At the start of a race he will jam on too much throttle, and his front wheel will leap into the air. He powershifts through the gears brutally. In the corners, burning tread off his tires, he wilLnudge slower riders out of the way. On dirt tracks he loves to slide and therefore is sideways practically all the time, always thrilling the crowd.

“There are other riders who are smoother than me,” he concedes. “Smoothness will come.”

Aldana was the best racer in the Amateur division last year, winning seven Nationals. At the final National at Ascot, which he also won, he outqualified all the Experts, including Lawwill. Later he was quoted' as saying that Lawwill had better watch out for him now, because he was going to walk all over him. When Lawwill heard this he smiled, shrugged, and intimated he did not care what Aldana said. He was only a long-haired kid.

Aldana snorted that he had been misquoted: “I’ve got enough trouble trying to beat guys like Lawwill without getting them sore at me.” Then he quickly added, “But if I didn’t know I could beat them, I wouldn’t be racing.”

Aldana’s father, a plasterer, raced motorcycles for a hobby in sportsman events years ago. Dave’s uncle is tuner Danny Macias. Aldana is Mexican-American, and bilingual. In high school he was on the football team, played trumpet in the band, raised pigeons, rats and snakes for a hobby at home, then began fiddling with slot racing cars, winning several trophies. At 14 he started racing a 50-cc Suzuki.

“Racing motorcycles takes more guts than racing slot cars,” he decided. So at 18 he turned professional, racing at Ascot without brakes. He must have been good, because he piled up several wins. Abruptly, he quit racing to go to junior college, but quit after a couple weeks. He and two friends booked tickets to go to Europe for a vacation in early 1 969.

Then the BSA team phoned him and asked that he ride in the Amateur races for them full time. At his first race, the Astrodome National in Houston, Aldana won. Before the season was done he would win seven Nationals, would also fall down several times, and finally take $15,000 in prize money back to Los Angeles. Dave spent part of it having T-shirts made with his picture on them; he plans to sell them to his adoring fans.

Now that he is in the Expert division, Aldana still races flat out. He rushes into the corners with little concern for the proper line. Because he is so small (5 feet 5, 135 lb.) he has to sweat to control his overpowered 300-lb. bike. But he is solidly built, and in his garage at home are some barbells that he heaves around to make himself tougher. “Most good motorcycle racers are small,” he says pointedly.

Like Brelsford, Rice and Castro he is single. He just turned 20 and seems shy, even suspicious, of strangers. When asked a question he will answer politely but curtly, never saying more than is absolutely necessary. Aldana does not impress one as having much of a personality.

“He’s not a smart rider now,” says an observer. “He rides with the throttle. He doesn’t use his head.” But Dick Mann says, “There is no doubt he is good.”

Some veterans tell Aldana to take it easy, to smooth out, but Dave doesn’t seem to hear them. He is winning races, isn’t he?

If he is to become really good he will have to be smoother. And he needs to learn patience. At the Daytona 200 in March, he started from the back and had to overtake nearly 100 riders.

He made a dazzling effort. He hurled his big BSA three-cylinder down the long straights at 165 mph and barged by rider after rider. With only a few miles remaining he had fought his way up to 5th. Then leader Dick Mann came up to lap him, and Aldana foolishly would not give way. He finally ran off the road and broke his bike trying to hold off Mann, losing much of the ground he had spent two hours making up.

Aldana is the most exciting and controversial of the younglings, and easily the fastest. The veterans mutter about his tactics. The other younglings are impressed. Says Mark Brelsford: “If I were a spectator, I’d watch Aldana more than anyone else.”

BEHIND A CALM FACE...

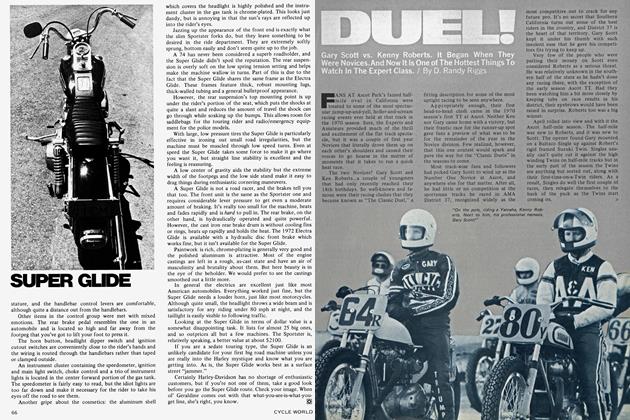

To observe Mark Brelsford wrench his beefy 8 8 3-cc Harley-Davidson around a hairpin is a joy. He appears controlled, poised, absolutely sure of himself. Veterans praise his coolness and tidy riding. But Mark Brelsford also is the type of rider the veterans fear most: the naturally talented guy who goes very fast and does not have to work at it.

His race track image is one thing. Away from the tracks, Brelsford fronts a much different image. “I was very unsure of myself when I started racing,” he says; “I didn’t have any confidence.” In some ways, surprisingly, he still lacks confidence.

Brelsford, from San Bruno in northern California, lives with his mother, stepfather, two brothers and four sisters. He started racing five years ago, thrashing a tiny Honda in scrambles races. Finding these too easy, he bought a professional license. He displayed a talent for jumping into the lead, then crashing. He would not slow up for corners.

Because Mark showed promise, the proprietor of a local motorcycle shop gave him a bike and $500 and sent him, in the summer of 1968, to some National races in the Midwest. Brelsford was anxious to do well but inwardly was scared: “I had no will to win at all. I didn’t know how I would do in the big time against the big guys. I’d only read about most of them.”

He toured and palled around with Mert Lawwill. Only 19 and still an Amateur, Brelsford was in awe of Lawwill and the other veteran Experts. He thought he could gain favor by mimicking their riding styles, and at Louisville, Kentucky, he willed himself to gun around the corners without shutting off the throttle, just like Lawwill. Mark was leading his heat race with ease when he crashed.

This won him, not the respect he expected, but scorn. “Kid, you weren’t riding with your head out there,” Mert Lawwill told him. “You had it won. Why did you fall off?”

After this, Brelsford says, “I tried to get my emotions under control.”

By the time the AMA circuit swung back to the West Coast he was out of money and had been borrowing heavily from Lawwill and some of the other Experts. To pay off his debts, he virtually had to win the $250 lst-place money at Portland. Using his newly-found discipline, did win. Bailing himself out of debt like this did wonders for his confidence.

Lawwill coached him for the rest of the season and loaned him factory Harley-Davidsons. Mark paid him half of any prize money he won. He won so many Amateur races that he was named “rider of the year.”

But in 1969, now an Expert himself and still Lawwill’s riding partner, all Brelsford could seem to do was crash. At the Daytona short-track a rider fell in front of him, and Mark rode up and over his fallen bike like a ramp. He was catapulted high in the air and slammed into the brick crashwall.

“I woke up on the stretcher in the hospital,” he recalls. “I looked up and saw Mert, and then I passed out again.” He had a broken right wrist, broken fingers, broken ankle and lacerations.

He was sent home to San Bruno to recuperate. He could not use his hands, and his mother had to hand-feed him, like a baby.

Almost as soon as he started racing again, he won his first National, the night TT steeplechase race at Ascot Park. He did not win it by riding like a fiend, but by cooly dogging, for lap after lap, the back wheel of leader Skip Van Leeuwen.

Van Leeuwen, the pressure undoing him, kept glancing over his shoulder at Brelsford and riding more and more raggedly, until he finally broke his engine with five laps remaining. Brelsford motored by calmly to win with ease.

He explained cooly, “I did not want to pass Van Leeuwen earlier, because I didn’t know what he would do if I did. I was planning my moves.”

A month later at Santa Fe Speedway in Chicago, only a week after he had nearly beaten Dick Mann and Neil Keen at the short track National, another rider banged into Mark, knocking him down and breaking his collarbone.

In the ambulance, the rider kept moaning, “I’m sorry,” “I’m sorry,” until Mark, gritting his teeth from the pain, forgave him. Then with his collarbone still in a brace, he held 2nd place at the Sears Point road race until the pain and heat made him stop, exhausted.

Now he says he is glad that he has experienced accidents and pain. “Before, I never knew if, when I got hurt bad, I would be able to ride again. Now I know that I can.”

Brelsford would seem to be the type of rider that the AMA wishes it had dozens of. Polite, well-scrubbed, small (5 feet 8, 130 lb.) he loves racing and never seems to complain about insufficient prize money or hazardous track conditions. He is amicable, easy to talk with, and his conversation is interesting, if not stimulating.

Brelsford completely lacks the “killer instinct,” and this may be to his disadvantage. “It’s difficult for me to be hostile towards anyone,” he smiles. He continues to look up to and idolize veterans like Lawwill. He is delighted he has at last turned 21 ; now he can drink beer with the rest of the group. But sometimes it seems as if he still lacks confidence in himself. At Daytona this year Mark refused to believe he could control his big Harley at 150 mph on the banking until Lawwill showed him how to do it. His future? “The only thing I care about is winning,” Mark said recently, displaying an outspoken intenseness which seemed unusual, coming from him. “I get so nervous before a race, all my food comes up. I have dreams of being No. 1; I’ll spend 10 years trying to get it if I have to.”

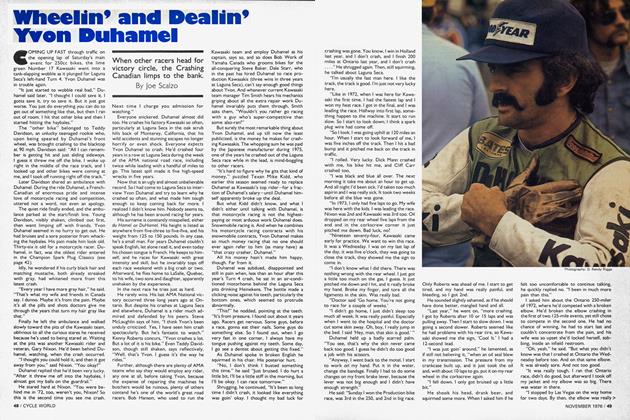

"WHO?" THE CROWD ASKED

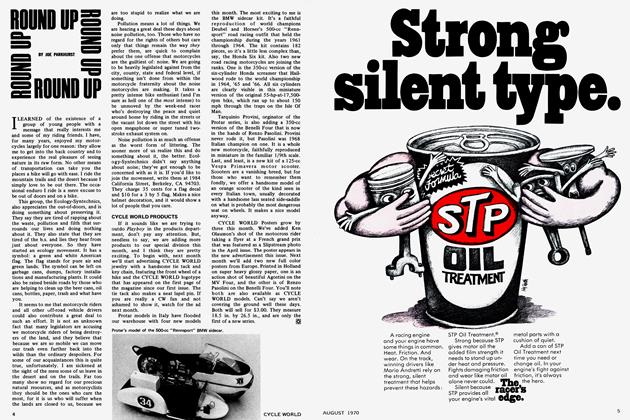

When Jim Rice won his first National last year, the crowd asked, “Who?”

Motorcycle racing does not like surprises. It likes to know what is going on at all times. Jim Rice’s easy victory at San Jose, Calif., over veterans Gary Nixon, Bart Markel, Mert Lawwill, Gene Romero and Chuck Palmgren was the biggest surprise of all. But no fluke.

Before the season was over Rice had added National wins at Sedaba, Mo., on the long, fast mile track, and later at Oklahoma City, a dry, slick half mile. At Sedaba, Rice had had to thread his way gingerly through a fire and a seven-rider pile-up directly in front of him.

He opened the 1970 season recently by easily winning the TT steeplechase National inside the Astrodome. In April he was again making news; this time he won the 20-lap dirt track National at Palmetto, Ga.

In less than 12 months, Rice has accounted for five National wins and has been made a member of the BSA team. His forte is hard, slippery, greasy, daytime dirt tracks. On a snaking paved road course, he is not very fast. He was not supposed to be a steeplechase rider either, yet he easily won at Houston. Through the ferocious traffic of the early laps he appeared from nowhere to seize the lead. While everyone behind him strained to keep from falling, Rice easily extended his margin every lap. He didn’t look like he was going fast.

Rice says his most rewarding win was at Palmetto. Dick Mann led the first five laps, then Rice passed him. Mann repassed him on the next to the last lap on the back straight. Rice was able to get the lead back from Mann on the final round, but he had to ride much harder than he wanted. “I was never more exhausted—physically and mentally—in my life,” he admitted afterwards.

“Usually they call me Jim ‘Smooth’ Rice,” he continued. “I like being smooth. I only fell two times in 1969.”

Rice’s advantage as a rider is that he knows pace and also possesses that little extra edge when it is needed. But no one seems to know what makes him tick. Puzzles Dave Aldana, “Rice just sits there before the start of a race looking mad at everybody, and then he goes out and wins.” Mark Brelsford says, “You have to understand how dedicated Jim is. He lives in a little house behind his parents in San Jose and works on his bikes all winter there. I think he enjoys working on his bikes more than any of the rest of us do.”

Rice says, “I’m not ice cold. I get butterflies. If you don’t get butterflies before a race starts, there’s something wrong with you.”

After he won his first National at San Jose, Rice says veteran Experts “began to know I was around.” Not that they were impressed. At the Sacramento 25-mile National, Chuck Palmgren moved up behind Rice and began prodding him with his front wheel. Rice nearly lost control in the corner, slid wide, and was passed by Palmgren on the inside. “He kept getting in my way,” Palmgren explained afterwards, cheerfully. Rice accepted this tough justice and went home to work more speed out of his bike. A couple of weeks later he won the Oklahoma City National.

Rice lives it up. His girl friend is a striking blond. When he is home he goes trailing in the hills with his best friend and neighbor, Mark Brelsford. He also likes to take his girl friend dancing in nearby San Francisco.

He is 22 years old, 6 feet 1, and weighs 160 lb., a lot of weight for a motorcycle racer to pack. Jim believes it gives him an advantage when accelerating off the corners.

There is nothing in his family background to suggest he should race motorcycles. His father drives a school bus. His mother works in a bank. A brother, three years older, is studying to be a doctor.

From past performances Rice has shown himself to be determined to excel in whatever he does. But then he becomes bored and disinterested and moves on to something new, another challenge.

His first motorcycle was a little Yamaha which he crashed continually. “I scraped up my knees every time I rode it.” This was in 1965. Within a few years he was the best scrambles rider in northern California. Fascinated with mechanical things, he took time out to build up some drag racing cars. He was not sure what he wanted to do, but finally decided to turn pro. He spent two years in the Amateur division, winning regularly. Eventually this bored him. “The competition in the Amateur ranks is not as stiff as with the experts. You have to have guts to be an Expert.”

(Continued on page 66)

Continued from page 47

So he entered the National at San Jose last year.

He jumped into the lead at the start. For three laps he rode as hard as he could, waiting for the veterans to come by him. Scared to death, he finally peeked over his shoulder—and saw that no one was close. He went on to win easily. Winning has been easy for him ever since, although he still needs to learn about road racing.

...A BAD LUCK BOY

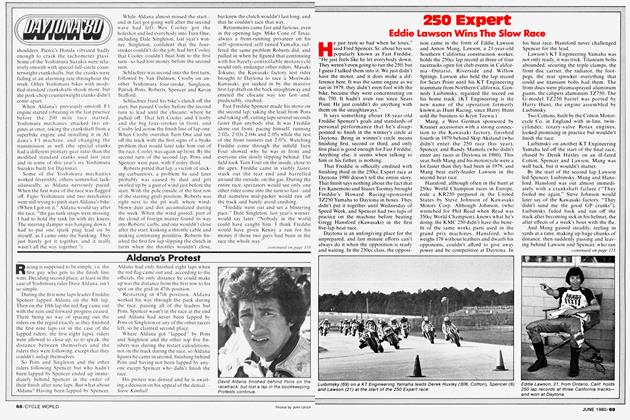

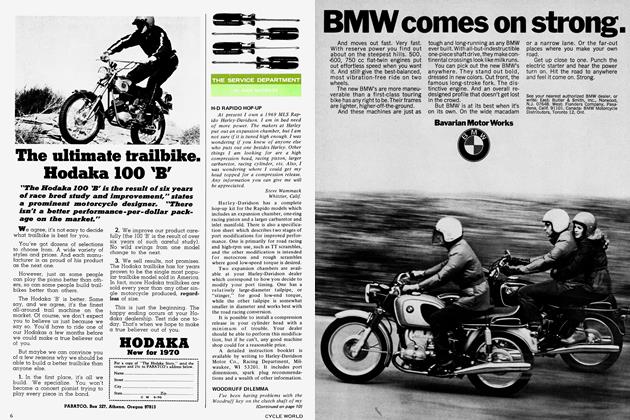

Without luck, no rider can win. Don Castro, of all the hot shoe younglings, seems to be the unluckiest.

He roared into 1969, announced by rave reviews. He and Dave Aldana were rated the two best Amateur division racers in America.

The fiery Aldana immediately polished off five straight races—Cumberland, Terre Haute, Nazareth, Reading, and Santa Fe. Castro, meanwhile, watched miserably from the sidelines. He had a broken ankle.

It was an absurd injury. No one had run over his foot. No one had knocked him down in the heat of battle. He broke it playing volleyball with Gary Nixon, after a race. Nixon and Castro, playing on the same team, had collided while going after the ball. Castro had fallen heavily, with Nixon on top of him.

A heavy plaster cast was placed around the swollen ankle. Don accompanied Nixon and the other riders to the races and watched Aldana, whom he was sure he could beat, rack up win after win. The frustration nagged at him.

But Castro, though only 20, is practical. Today he looks upon this convalescence period as being good for him: “Just sitting back watching, not being able to ride, made me all the more anxious and determined to race again.”

Finally the torture became too great; he couldn’t wait any longer. He took a saw and sliced off half the cast so that he could wiggle his ankle. It felt fine. Racing this way, with half a cast, he won six Nationals to his bitter rival, Aldana’s, none.

The last National of the year was at Ascot in Los Angeles.

As the contest started, Castro snatched the lead. An accident on the first lap brought out the black flag. On the re-start, Castro led again, with Aldana a menacing second. Castro reached up to quickly brush some dirt off his goggles and inadvertantly pulled them off. Dirt and rocks were swirling through the air, and it was impossible to see without goggles. Castro had to stop.

Along with his bad luck came impressive performances. At Sedalia on the mile track last year he was the fastest qualifier over all the Experts, and won the Amateur main event by a full straightaway. At Sacramento, also a mile track, he fell at 100 mph while leading his heat race and was passed by everyone. He calmly remounted, then caught and passed the field again. He went on to win the Amateur main, too.

Those who know him best describe Castro as bashful, which he is. He is quick to praise his mechanics and his bikes, but has little to say about himself.

His background is improbable. He was born, and still lives today, in Hollister, a northern California farming town made famous by the motorcycle riot on which the film, “The Wild One,” was based. Don loved motorcycles from the beginning, but his father forbade him to ride one on the street.

Heartbroken, Don tried a new approach: if he couldn’t ride on the street, could he race at the town’s scrambles track? His father said yes. Hip father!

To this day, though he has been racing four years, Castro has never ridden a motorcycle on the street.

He opened up 1970 as a factory Triumph rider, placing a stunning 3rd at Daytona, his first big road race. It was the first time he had ever ridden so far (200 miles) and so fast (160 mph). He followed this up with high finishes at Kent and Palmetto and, as the summer was starting, found himself listed among the country’s top 10 riders.

Asked if he thought he could win No. 1 in his first year as an Expert, the bashfulness came through: “Gee, it

would be kind of fantastic. There are a lot of races still to go.” But he was not ruling out the idea completely.

Then, like a thunderclap, came news of Castro’s latest bad luck. He was to receive his induction papers from the Army, and it appeared he might have to quit racing for an indefinite period. “I’m pretty worried about it,” was all he would say.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

August 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

August 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

August 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Features

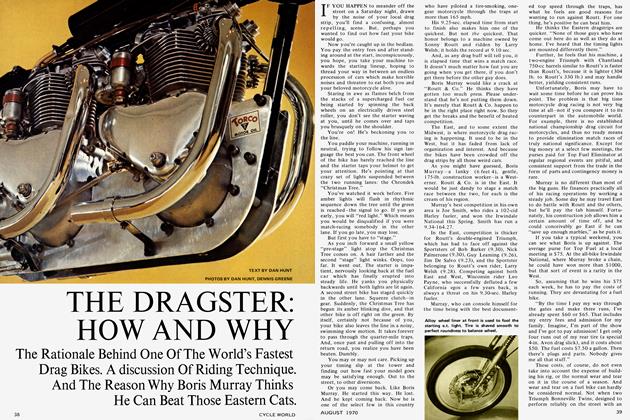

Special FeaturesThe Dragster: How And Why

August 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesThe Princess & the Peasant

August 1970 By Cecil P. Mack