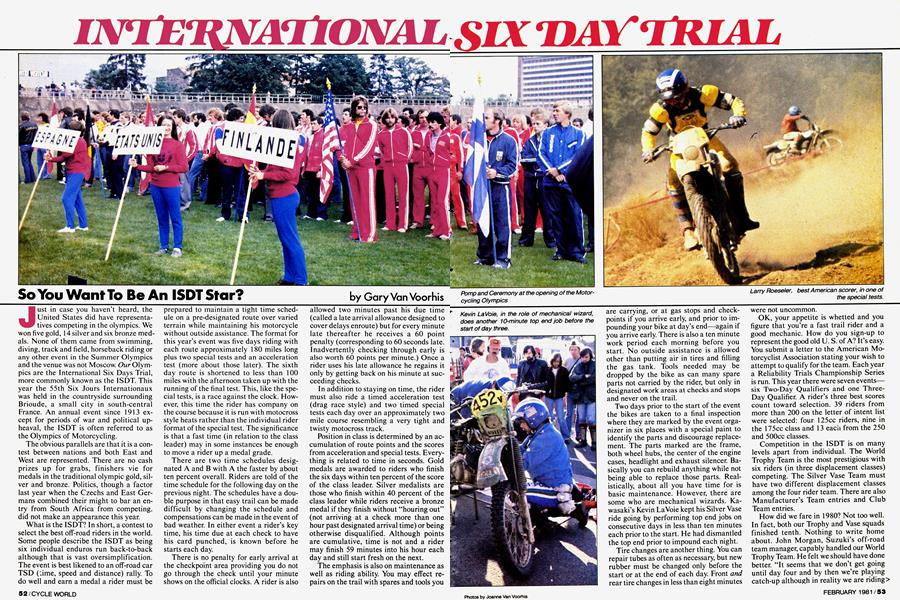

INTERNATIONAL SIX DAY TRIAL

So You Want To Be An ISDT Star?

Gary Van Voorhis

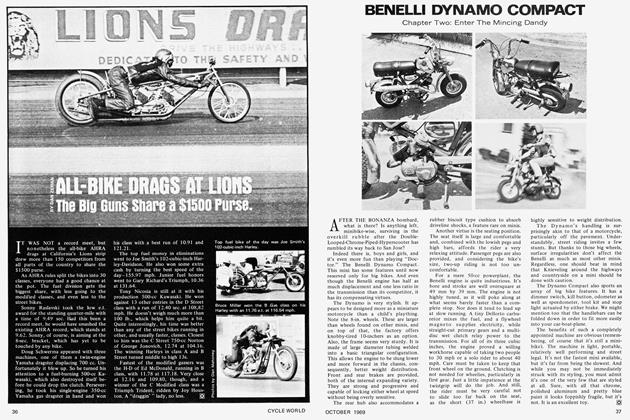

Just in case you haven't heard, the United States did have representatives competing in the olympics. We won five gold, 14 silver and six bronze medals. None of them came from swimming, diving, track and field, horseback riding or any other event in the Summer Olympics and the venue was not Moscow Our Olympics are the International Six Days Trial, more commonly known as the ISDT. This year the 55th Six Jours Internationaux was held in the countryside surrounding Brioude, a small city in south-central France. An annual event since 1913 except for periods of war and political up-heaval, the ISDT is often referred to as the Olympics of Motorcycling.

The obvious parallels are that it is a con test between nations and both East and West are represented. There are no cash prizes up for grabs, finishers vie for medals in the traditional olympic gold, sil ver and bronze. Politics, though a factor last year when the Czechs and East Ger mans combined their might to bar an en try from South Africa from competing. did not make an appearance this year.

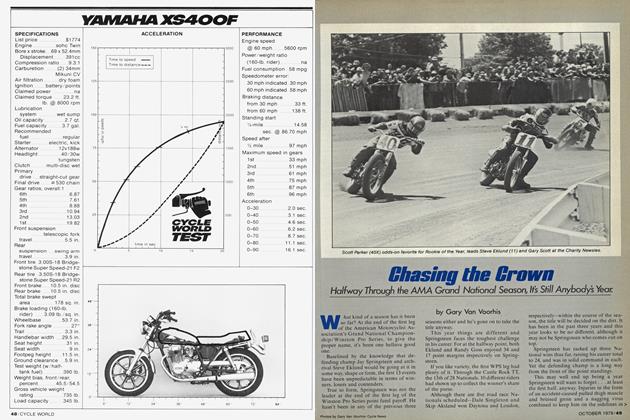

What is the ISDT? In short, a contest to select the best off-road riders in the world. Some people describe the ISDT as being six individual enduros run back-to-back although that is vast oversimplification. The event is best likened to an off-road car TSD (time, speed and distance) rally. To do well and earn a medal a rider must be prepared to maintain a tight time sched ule on a pre-designated route over varied terrain while maintaining his motorcycle without outside assistance. The format for this year's event was five days riding with each route approximately 180 miles long plus two special tests and an acceleration test (more about those later). The sixth day route is shortened to less than 100 miles with the afternoon taken up with the running of the final test. This, like the spe cial tests, is a race against the clock. How ever, this time the rider has company on the course because it is run with motocross style heats rather than the individual rider format of the special test. The significance is that a fast time (in relation to the class leader) may in some instances be enough to move a rider up a medal grade.

There are two time schedules desig nated A and B with A the faster by about ten percent overall. Riders are told of the time schedule for the following day on the previous night. The schedules have a dou ble purpose in that easy trail can be made difficult by changing the schedule and compensations can be made in the event of bad weather. In either event a rider's key time, his time due at each check to have his card punched, is known before he starts each day.

There is no penalty for early arrival at the checkpoint area providing you do not go through the check until your minute shows on the official clocks. A rider is also allowed two minutes past his due time (called a late arrival allowance designed to cover delays enroute) but for every minute late thereafter he receives a 60 point penalty (corresponding to 60 seconds late. Inadvertently checking through early is also worth 60 points per minute.) Once a rider uses his late allowance he regains it only by getting back on his minute at suc ceeding checks.

In addition to staying on time, the rider must also ride a timed acceleration test (drag race style) and two timed special tests each day over an approximately two mile course resembling a very tight and twisty motocross track.

Position in class is determined by an ac cumulation of route points and the scores from acceleration and special tests. Every thing is related to time in seconds. Gold medals are awarded to riders who finish the six days within ten percent of the score of the class leader. Silver medalists are those who finish within 40 percent of the class leader while riders receive a bronze medal if they finish without "houring out" (not arriving at a check more than one hour past designated arrival time) or being otherwise disqualified. Although points are cumulative, time is not and a rider may finish 59 minutes into his hour each day and still start fresh on the next.

The emphasis is also on maintenance as well as riding ability. You may effect re pairs on the trail with spares and tools you are carrying, or at gas stops and checkpoints if you arrive early, and prior to impounding your bike at day’s end—again if you arrive early. There is also a ten minute work period each morning before you start. No outside assistance is allowed other than putting air in tires and filling the gas tank. Tools needed may be dropped by the bike as can many spare parts not carried by the rider, but only in designated work areas at checks and stops and never on the trail.

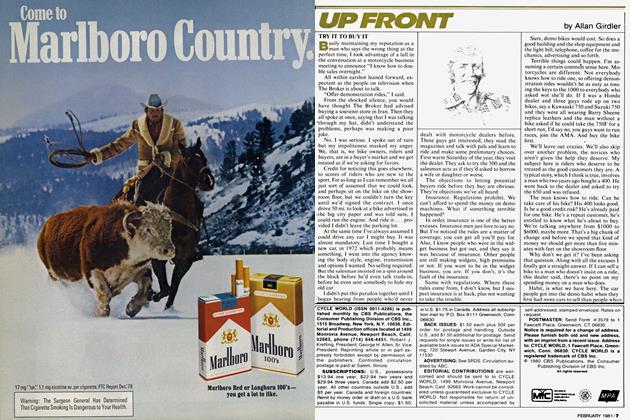

Two days prior to the start of the event the bikes are taken to a final inspection where they are marked by the event organizer in six places with a special paint to identify the parts and discourage replacement. The parts marked are the frame, both wheel hubs, the center of the engine cases, headlight and exhaust silencer. Basically you can rebuild anything while not being able to replace those parts. Realistically, about all you have time for is basic maintenance. However, there are some who are mechanical wizards. Kawasaki’s Kevin LaVoie kept his Silver Vase ride going by performing top end jobs on consecutive days in less than ten minutes each prior to the start. He had dismantled the top end prior to impound each night.

Tire changes are another thing. You can repair tubes as often as necessary, but new rubber must be changed only before the start or at the end of each day. Front and rear tire changes in less than eight minutes were not uncommon.

OK, your appetite is whetted and you figure that you’re a fast trail rider and a good mechanic. How do you sign-up to represent the good old U. S. of A? It’s easy. You submit a letter to the American Motorcyclist Association stating your wish to attempt to qualify for the team. Each year a Reliability Trials Championship Series is run. This year there were seven events— six Two-Day Qualifiers and one ThreeDay Qualifier. A rider’s three best scores count toward selection. 39 riders from more than 200 on the letter of intent list were selected: four 125cc riders, nine in the 175cc class and 13 each from the 250 and 500cc classes.

Competition in the ISDT is on many levels apart from individual. The World Trophy Team is the most prestigious with six riders (in three displacement classes) competing. The Silver Vase Team must have two different displacement classes among the four rider team. There are also Manufacturer’s Team entries and Club Team entries.

How did we fare in 1980? Not too well. In fact, both our Trophy and Vase squads finished tenth. Nothing to write home about. John Morgan, Suzuki’s off-road team manager, capably handled our World Trophy Team. He felt we should have done better. “It seems that we don’t get going until day four and by then we’re playing catch-up although in reality we are riding > as well or better than the top teams at that point in time. We have riders as good as the other teams have, but we need to get started earlier and also become adept at playing the game as well as the rest do.”

INDIVIDUAL AMERICAN FINISHERS

RETIREMENTS

P1a~ing the game is another way of de scribing rider support and it involves a lot of things.

Major among them is having support riders. In the U.S. we sort of assume that each rider is out there by himself with the teams helping at gas stops, etc. But in the ISDT the teams are out on the trail, in the form of support riders. These are skilled riders who scout the day’s course and brief the actual competing rider on where tough parts are and where he can make up time. Support riders also can ride in front of their entrant, or behind, ready to drop spare parts on the trail or give mechanical advice. You have to call it creative maintenance because it’s all legal and therefore not cheating. The bottom line is, it’s part of the ISDT and those who’ve perfected it into a science usually finish high on the charts.

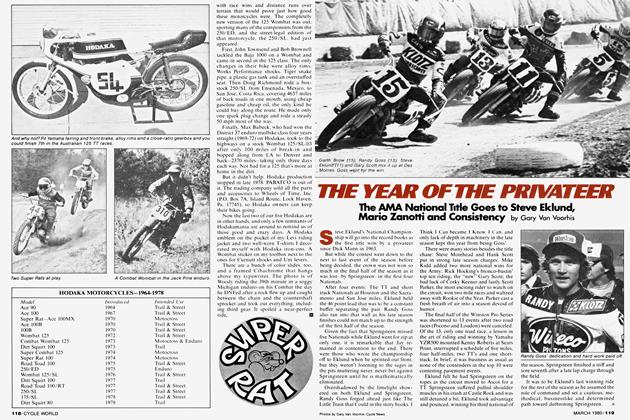

The Italians won the World Trophy for the second consecutive year. They had two support riders on the trail—one riding in front and one behind—for each member of both their World Trophy and Silver Vase efforts. The tally for the Italian World Trophy members reads three class wins, two second place finishes in those same classes and one third place. The result is a tribute to the military-style campaign waged by the Italians, but it was also proof that they rode well, as massive support groups were more the rule than the exception.

The American effort, by contrast, had just four support riders to help the entire team. Further, it’s easier to carry parts for one brand, while our Trophy Team was riding four brands. Our support riders were all volunteers and they did a helluva job.

So did our trophy team, which consisted of Dick Burleson, Frank Gallo and Ed Lojak riding for Husky; Larry Roeseler of Yamaha, Mike Rosso for Suzuki and KTM’s Frank Stacy. They had everything except a bit of good luck.

We were in eighth place by the end of day one, after Stacy had problems in one special test and Lojak ran into tire trouble. Our overall score rose considerably when Stacy went out with transmission problems on day three. (15,000 penalty points are added for each non-finisher per day). Frank Gallo went out on day four in an accident while trying to make up time on a road section. Both problems might have been avoided with proper support.

The Vase team had Kawasaki’s Jack Penton, riding in his eleventh ISDT, and Kevin LaVoie combined with Suzuki riders John Ayers and Jeff Fredette. Fredette replaced Teddy Leimbach when he was seriously injured in an auto accident just prior to the ISDT. Leimbach died

continued on page 159

View Full Issue

View Full Issue