THE ONE-POINT YEAR

Gary Van Voorhis

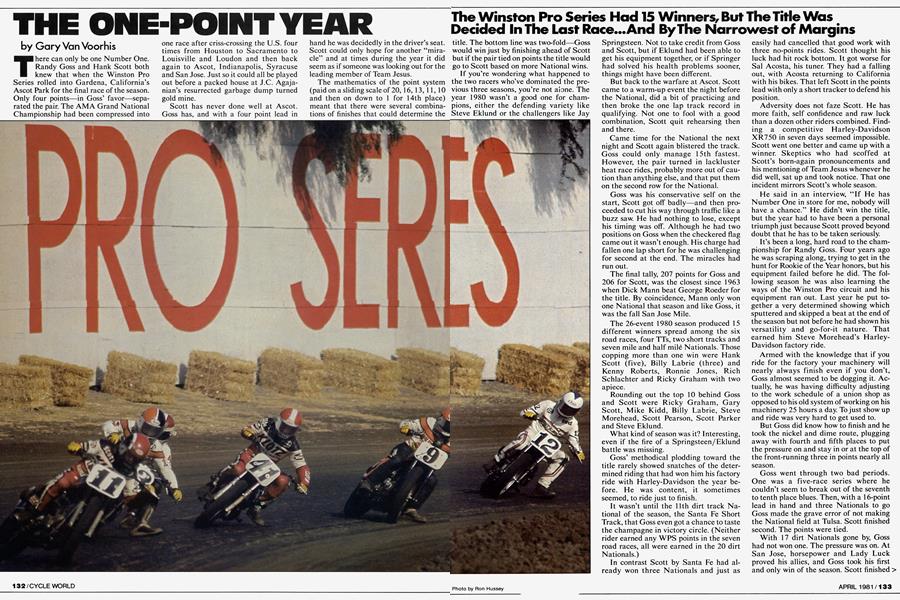

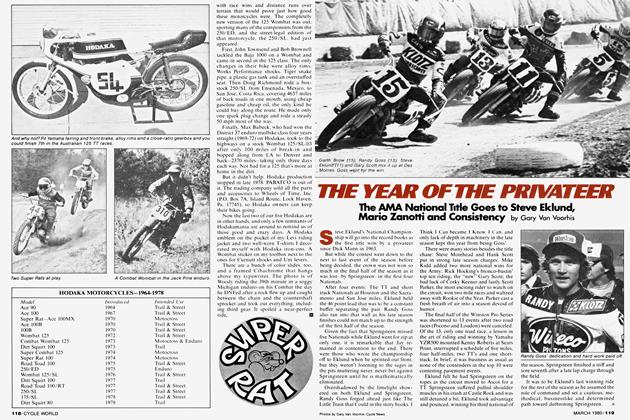

There can only be one Number One. Randy Goss and Hank Scott both knew that when the Winston Pro Series rolled into Gardena, California's Ascot Park for the final race of the season. Only four points—in Goss' favor—separated the pair. The AMA Grand National Championship had been compressed into one race after criss-crossing the U.S. four times from Houston to Sacramento to Louisville and Loudon and then back again to Ascot, Indianapolis, Syracuse and San Jose. Just so it could all be played out before a packed house at J.C. Agajanian’s resurrected garbage dump turned gold mine.

Scott has never done well at Ascot. Goss has, and with a four point lead in hand he was decidedly in the driver’s seat. Scott could only hope for another “miracle” and at times during the year it did seem as if someone was looking out for the leading member of Team Jesus.

The mathematics of the point system (paid on a sliding scale of 20,16,13,11,10 and then on down to 1 for 14th place) meant that there were several combinations of finishes that could determine the title. The bottom line was two-fold—Goss would win just by finishing ahead of Scott but if the pair tied on points the title would go to Scott based on more National wins.

The Winston Pro Series Had 15 Winners, But The Title Was Decided In The Last Race...And By The Narrowest of Margins

If you’re wondering what happened to the two racers who’ve dominated the previous three seasons, you’re not alone. The year 1980 wasn’t a good one for champions, either the defending variety like Steve Eklund or the challengers like Jay Springsteen. Not to take credit from Goss and Scott, but if Eklund had been able to get his equipment together, or if Springer had solved his health problems sooner, things might have been different.

But back to the warfare at Ascot. Scott came to a warm-up event the night before the National, did a bit of practicing and then broke the one lap track record in qualifying. Not one to fool with a good combination, Scott quit rehearsing then and there.

Came time for the National the next night and Scott again blistered the track. Goss could only manage 15th fastest. However, the pair turned in lackluster heat race rides, probably more out of caution than anything else, and that put them on the second row for the National.

Goss was his conservative self on the start, Scott got off badly—and then proceeded to cut his way through traffic like a buzz saw. He had nothing to lose, except his timing was off. Although he had two positions on Goss when the checkered flag came out it wasn’t enough. His charge had fallen one lap short for he was challenging for second at the end. The miracles had run out.

The final tally, 207 points for Goss and 206 for Scott, was the closest since 1963 when Dick Mann beat George Roeder for the title. By coincidence, Mann only won one National that season and like Goss, it was the fall San Jose Mile.

The 26-event 1980 season produced 15 different winners spread among the six road races, four TTs, two short tracks and seven mile and half mile Nationals. Those copping more than one win were Hank Scott (five), Billy Labrie (three) and Kenny Roberts, Ronnie Jones, Rich Schlachter and Ricky Graham with two apiece.

Rounding out the top 10 behind Goss and Scott were Ricky Graham, Gary Scott, Mike Kidd, Billy Labrie, Steve Morehead, Scott Pearson, Scott Parker and Steve Eklund.

What kind of season was it? Interesting, even if the fire of a Springsteen/Eklund battle was missing.

Goss’ methodical plodding toward the title rarely showed snatches of the determined riding that had won him his factory ride with Harley-Davidson the year before. He was content, it sometimes seemed, to ride just to finish.

It wasn’t until the 11th dirt track National of the season, the Santa Fe Short Track, that Goss even got a chance to taste the champagne in victory circle. (Neither rider earned any WPS points in the seven road races, all were earned in the 20 dirt Nationals.)

In contrast Scott by Santa Fe had already won three Nationals and just as easily had cancelled that good work with three no-points rides. Scott thought his luck had hit rock bottom. It got worse for Sal Acosta, his tuner. They had a falling out, with Acosta returning to California with his bikes. That left Scott in the points lead with only a short tracker to defend his position.

Adversity does not faze Scott. He has more faith, self confidence and raw luck than a dozen other riders combined. Finding a competitive Harley-Davidson XR750 in seven days seemed impossible. Scott went one better and came up with a winner. Skeptics who had scoffed at Scott’s born-again pronouncements and his mentioning of Team Jesus whenever he did well, sat up and took notice. That one incident mirrors Scott’s whole season.

He said in an interview, “If He has Number One in store for me, nobody will have a chance.” He didn’t win the title, but the year had to have been a personal triumph just because Scott proved beyond doubt that he has to be taken seriously.

It’s been a long, hard road to the championship for Randy Goss. Four years ago he was scraping along, trying to get in the hunt for Rookie of the Year honors, but his equipment failed before he did. The following season he was also learning the ways of the Winston Pro circuit and his equipment ran out. Last year he put together a very determined showing which sputtered and skipped a beat at the end of the season but not before he had shown his versatility and go-for-it nature. That earned him Steve Morehead’s HarleyDavidson factory ride.

Armed with the knowledge that if you ride for the factory your machinery will nearly always finish even if you don’t, Goss almost seemed to be dogging it. Actually, he was having difficulty adjusting to the work schedule of a union shop as opposed to his old system of working on his machinery 25 hours a day. To just show up and ride was very hard to get used to.

But Goss did know how to finish and he took the nickel and dime route, plugging away with fourth and fifth places to put the pressure on and stay in or at the top of the front-running three in points nearly all season.

Goss went through two bad periods. One was a five-race series where he couldn’t seem to break out of the seventh to tenth place blues. Then, with a 16-point lead in hand and three Nationals to go Goss made the grave error of not making the National field at Tulsa. Scott finished second. The points were tied.

With 17 dirt Nationals gone by, Goss had not won one. The pressure was on. At San Jose, horsepower and Lady Luck proved his allies, and Goss took his first and only win of the season. Scott finished second and the stage was set for Ascot.

Ricky Graham, who was third in the final standings, lurked in the shadows just waiting for a mistake in the last third of the season. His season had been full of ups and downs—usually when exuberance got the better of patience.

He collected both his National wins during the last races, blistering the daytime Indianapolis Mile with an average speed of over 100 mph for the 25 lap event. It was the first time in AMA history that anyone had done that on the dirt. (It was a day for records. Hank Scott’s record-breaking qualification time of 102.032 mph upped his previous record by nearly 2 mph.) Graham left Indy second in the point standings.

Graham also won at Tulsa, leading Scott home and pulling within six points of co-leaders Goss and Scott. However, at San Jose his luck ran out and in the National, a crash, (caused by an overinflated rear tire losing traction), put him out of the hunt.

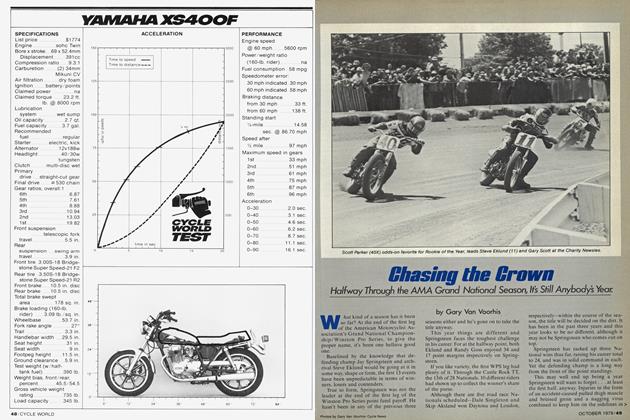

Gary Scott came back. He wasn’t really away, but his past three seasons had been marred by problems of all types and it seemed he had lost his touch. That all changed. Hank’s elder brother returned with the drive, style and consistency that earned him the Grand National Championship in 1975.

Gary Scott began to pick up momentum heading into mid-season and just kept rolling along, picking up the win in the Syracuse Mile. Having been shut out for the first time in eight seasons last year, his 17th career National win was doubly sweet. “It’s been a long time,” he said after spraying liberal amounts of champagne, “but it sure feels good.”

The tuning ability that kept Gary Scott in the top 10 seemed to be getting better. A good mechanic to begin with, he was content to build engines to last rather than tuning in an unreliability factor by tweaking for extra power. Syracuse was a gamble that worked. Once a winner, always a winner and in Scott’s case a lot of people were glad to see him back on top.

Mike Kidd could have been right there in the fight for the title at the end, but equipment problems when he least needed them let him down. Kidd couldn’t match his triple National winning season of 1979, but finished the same (fifth) in the standings.

Interestingly, his single National win came at Ascot in the TT National. Kidd is regarded as a good all-around rider although TT events would have to be the least of his strengths. Not only did he win the National, but he did it on a 500cc fourstroke Honda, proving that in the right situation light is might.

Kidd went into the final National at Ascot four points up on Scott. However, a stomach virus got the better of him after one lap of practice and he called it quits, too sick to race. That was doubly bitter since he had also lost fourth in the standings last year at the Ascot finale.

Billy Labrie owned Ascot. He won both half mile Nationals, which hadn’t been done before. The track, once a west coast domain, has seen east coast riders dominate the last five half mile Nationals.

Personable Labrie is a new face to some. Others will remember him as a road racer. In actuality he is a dirt tracker turned road racer who found the pavement too expensive and spent nearly three seasons putting together a dirt track program.

His season was run on a shoestring. He lacked a competitive short tracker and because he is a good short track rider it hurt. He did manage to pick up some points on a borrowed TT bike at Santa Fe. Labrie is not a TT rider, but managed to hustle a much changed Jimmy Filice’s factory Yamaha (Filice is barely five feet tall, Labrie is over six feet) to fourth.

If there is one trait to remember about Labrie it is his honesty. He had a ride on the sidelined Springsteen’s factory bike for both Indy Miles. He rode the night event and then opted for his bike the next day on the grounds it suited his style more. It takes guts to do that.

As probably the purest privateer— meaning the rider with the least monetary support—Labrie speaks from experience when he says it’s very hard to make any money. The money from three National wins and both WPS point fund payoffs look good on paper, but don’t really pay for the effort put in.

Steve Morehead is probably still wondering what happened to the momentum he had at the beginning of the season. Morehead, a notorious late starter, caught fire almost immediately and hit the halfway point of the season second in the point standings. That streak included his fourth career National win (Harrington) and a trio of top five finishes.

However, from there to the end of the season it was as if he could not beg, borrow or steal anything. The last half of the season included only one top five finish—a fifth at Indy.

He started the season with something to prove. Morehead lost his H-D factory ride to Randy Goss and wasn’t pleased. “Kick the factory’s ass,” was his goal and he set about doing that with none other than Goss’ father-in-law as his tuner. Unfortunately, a run of equipment troubles halted his charge and turned early-season elation into late season disappointment.

Scott Pearson seemed to be fulfilling the predictions heard when he broke in as a rookie four seasons ago. A broken wrist ended his first year and Pearson has been battling to make up for lost time ever since. He really hit stride this year before the Peoria TT, but it was there he put in a superb showing.

Peoria 1979 was also Pearson’s day of glory. His ride—leading winner Springsteen for 20 of the 25 laps—was best to that date. Peoria 1980 changed that second place to a first. Pearson dominated the race to round up his first tional win and then break into the top 10 points, tied in the final standings at eighth with Scott Parker and Steve Eklund.

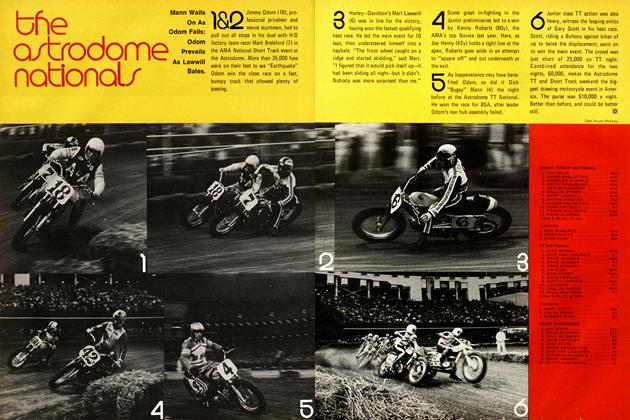

Having just turned 19 in November, Scott Parker can’t legally buy a drink in number of states in the U.S. That doesn’t keep him from drinking champagne winner’s circle.

Parker had no business winning Santa Fe Short Track National, not with Terry Poovey, Steve Eklund and Randy Goss on his rear tire. His ride was an electrifying one, but not in the typical Parker mold that has made him the most exciting rider to watch. Instead it was calculated and orderly just as Bill Werner had told Scott to do. Parker was on the sidelined

Jay Springsteen’s short tracker.

Apparently, what Werner had told Parker prior to the start set a fire. When the man who has been Parker’s tutor, mentor, sponsor, butt kicker and much more, Rick Toldo, just shakes his head muttering, “I don’t believe it,” you know it was a helluva show.

The bottom line for Steve Eklund is that it was a dismal season. That would be bad enough for one of the premier riders, but when you consider that he was defending the championship title he won last year in brilliant style, then it looks even worse.

Eklund didn’t even pick up a Winston Pro Series point until his fifth National— enough to make anyone think twice about the luck of racing. But that wasn’t all. Eklund was reduced in too many instances to fighting for crumbs at the back of the field.

It was probably too much. Machine preparation, money and time all ran out for Eklund. It just seemed that he could do no right. Yes, he did shine at the Santa Fe Nationals where he seems to own the track, but this year he could manage only third and fourth place finishes (short track and TT) in events he won last year. Not only that, but Eklund was shut out completely from winning any Nationals. Having racked up 13 wins in his previous four seasons, it was like a slap in the face.

Eklund even packed it in for two Nationals (Syracuse and Tulsa) to go back to his San Jose home and spend those two weeks getting his program back on the right track. The effort paid off. He was a strong third at San Jose before closing out the season with a second place finish—his best of the year—at Ascot. In those two races he looked like Steve Eklund The Champion. Those performances salvaged

some self respect as Eklund managed to finish in a tie for eighth place.

Who can say what psychological toll was taken on Jay Springsteen? After nearly two years of not knowing what his health problem was, it was finally diagnosed as a borderline case of diabetes . . . borderline in the sense that it could be treated via diet and such rather than insulin.

Springer only rode five Nationals, spending much of the rest of the time somewhere in the woods of northern Michigan hunting and fishing while awaiting decisions by doctors and Harley-Davidson on whether he was fit enough to return to action. Harley set him down twice in the season trying to find out what was wrong. However, discovering the reason for the illness and returning Jay to 100 percent health were two different things.

He may have ridden in only five Nationals, but he made his presence felt with three top five finishes. In his two other rides Springer was right up near the front, only to have a tire problem in one instance and an unavoidable crash in the other ruin his challenge.

He was his old self at the final National, congratulating Harley-Davidson teammate Randy Goss on winning the championship, joking around and apparently in good health as well as good spirits.

The road racing end of the Winston Pro Series, expanded to six Nationals for 1980, produced five winners with only Rich Schlachter winning more than once.

Frenchman Patrick Pons became the fourth foreign rider to win the Daytona’ 200 in the past nine years. Pons was later killed in a GP road racing accident.

The change to Formula One racing from F750 allowing unrestricted 1025cc four-strokes to compete with unrestricted 500cc two-strokes and restricted 750cc two-strokes proved to be popular and competitive. In the second road racing National Wes Cooley put his Yoshimura Suzuki four-stroke ahead of everyone else on the nearly four mile circuit at Elkhart Lake.

Schlachter established himself as the rider to beat in American road racing and filled the void left by the defection to Europe by Kenny Roberts, Randy Mamola and Dale Singleton. Schlachter rolled merrily on his way at both Laconia and Road Atlanta.

Kenny Roberts blitzed the competition at Laguna Seca and in doing so won his 29th career National (he had won the 28th at the Houston TT National after being away from dirt track for two full seasons) and thus became the winningest rider in AMA Grand National Championship history.

Dale Singleton came home from the rigors of his first year in Europe to run Pocono and left everyone well behind. It was a surprise for Singleton since he was barely able to make the fields in only a couple of the GP’s. “The difference between European racing and racing here is night and day,” he said.

Meanwhile, plugging away unnoticed by nearly everyone was Nick Richichi. He neatly upset the plans of Bubba Shogert for Rookie of the Year and took the title with points racked up through hard riding. Richichi finished second to Schlachter at Loudon for his best finish. It was the first time a pure road racer won the Rookie of the Year title.

The tentative schedule for 1981 will see the riders doing a bit less travel as the circuit has been finally set into one big loop—the traditional kickoff at Houston, then to the west coast, then a long eastern swing before finishing back at Ascot.

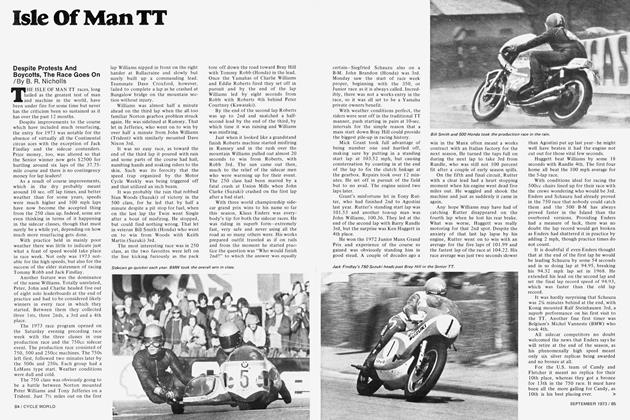

WINSTON PRO SERIES FINAL STANDINGS: