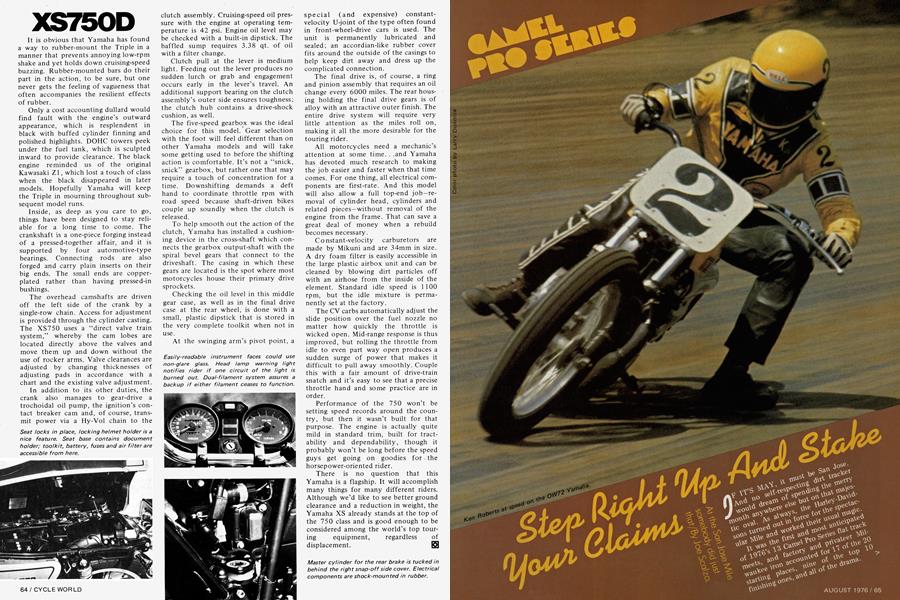

CAMEL PRO SERIES

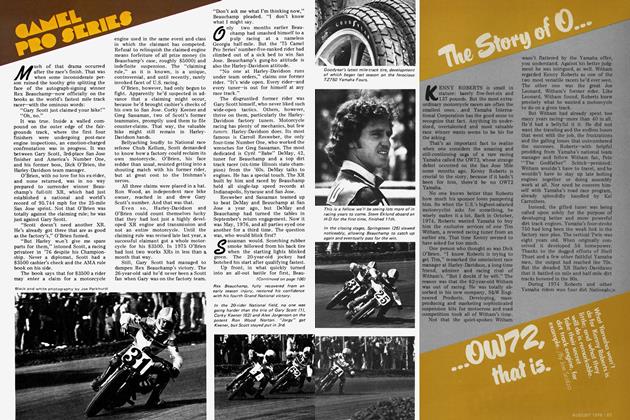

Much of that drama occurred after the race’s finish. That was when some inconsiderate person ruined the toothy grin splitting the face of the autograph-signing winner Rex Beauchamp—now officially on the books as the world’s fastest mile track racer—with the ominous words:

“Gary Scott just claimed your bike!” “Oh, no.”

It was true. Inside a walled compound on the outer edge of the fairgrounds track, where the first four finishers were undergoing post-race engine inspections, an emotion-charged confrontation was in progress. It was between Gary Scott, 3rd-place San Jose finisher and America’s Number One, and his former boss, Dick O’Brien, the Harley-Davidson team manager.

O’Brien, with no love for his ex-rider, and none returned, was in no way prepared to surrender winner Beauchamp’s full-tilt XR, which had just established a national and world’s record of 95.744 mph for the 25-mile San Jose sprint. Not that O’Brien was totally against the claiming rule; he was just against Gary Scott.

“Scott doesn’t need another XR. He’s already got three that are as good as the factory’s,” O’Brien fumed.

“But Harley won’t give me spare parts for them,” intoned Scott, a racing privateer in ’76 despite his Championship. Never a diplomat, Scott had a $3500 cashier’s check and the AMA rule book on his side.

The book says that for $3500 a rider may enter a claim for a motorcycle engine used in the same event and class in which the claimant has competed. Refusal to relinquish the claimed engine means forfeiture of all prize money (in Beauchamp’s case, roughly $5000) and indefinite suspension. The “claiming rule,” as it is known, is a unique, controversial, and until recently, rarely invoked facet of U.S. racing.

O’Brien, however, had only begun to fight. Apparently he’d suspected in advance that a claiming might occur, because he’d brought cashier’s checks of his own to San Jose. Corky Keener and Greg Sassaman, two of Scott’s former teammates, promptly used them to file counter-claims. That way, the valuable bike might still remain in HarleyDavidson hands.

Bellyaching loudly to National race referee Chub Kellum, Scott demanded to know how a factory could reclaim its own motorcycle. O’Brien, his face redder than usual, resisted getting into a shouting match with his former rider, but at great cost to the Irishman’s nerves.

All three claims were placed in a hat. Ron Wood, an independent race bike owner, reached in and drew Gary Scott’s number. And that was that.

Even so, Harley-Davidson and O’Brien could count themselves lucky that they had lost just a highly developed XR engine and transmission and not an entire motorcycle. Until the claiming rule was revised late last year, a successful claimant got a whole motorcycle for his $3500. In 1975 O’Brien had lost two works XRs in less than a month that way.

Still, Gary Scott had managed to dampen Rex Beauchamp’s victory. The 26-year-old said he’d never been a Scott fan when Gary was on the factory team. “Don’t ask me what I’m thinking now,” Beauchamp pleaded. “I don’t know what I might say.

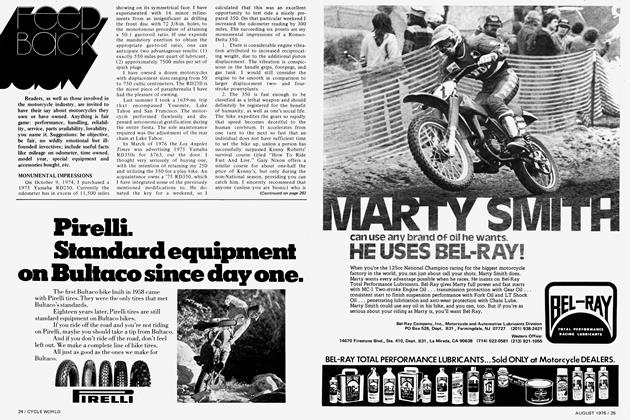

nly two months earlier Beaux'O champ had smashed himself to a pulp racing at a nameless Georgia half-mile. But the ’75 Camel Pro Series’ number-five-ranked rider had climbed out of a sick bed to win San Jose. Beauchamp’s gung-ho attitude is also the Harley-Davidson attitude.

“No one at Harley-Davidson runs under team orders,” claims one former rider. “It’s wide open. Every rider-and every tuner—is out for himself at any race track.”

The disgruntled former rider was Gary Scott himself, who never liked such wide-open tactics. Others, however, thrive on them, particularly the HarleyDavidson factory tuners. Motorcycle racing has plenty of mechanics, but few tuners. Harley-Davidson does. Its most famous is Carroll Resweber, the only four-time Number One, who worked the wrenches for Greg Sassaman. The most dedicated is Cyril “Babe” DeMay, 42, tuner for Beauchamp and a top dirt track racer (six-time Illinois state champion) from the ’60s. DeMay talks to engines. He has a special touch. The XR built by him and raced by Beauchamp held all single-lap speed records at Indianapolis, Syracuse and San Jose.

Resweber and Sassaman teamed up to beat DeMay and Beauchamp at San Jose a year ago, but DeMay and Beauchamp had turned the tables in September’s return engagement. Now it was May, 1976, and all parties eyed one another for a third time. The question was, who would blink first?

Sassaman would. Scorching rubber smoke billowed from his back tire when the starting lights blinked green. The 20-year-old jockey had botched his start after qualifying fastest.

Up front, in what quickly turned into an all-out battle for first, Beauchamp was getting the race of his life from Jay Springsteen, at 18 the baby of the H-D team. Fifty feet behind, Corky Keener was looking for racing room on yet another team bike. Already Keener had attracted the serious attention of Gary Scott’s blue privateer Harley and Alex Jorgensen’s Norton—the lone poacher in the otherwise all orange-andblack San Jose reserve.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 66

By 10 miles a heavy coating of rubber was accumulating on the corners from the new and controversial Goodyear mile tires. Openings were finally appearing in the swerving lanes of traffic ahead of him and Sassaman was finding them. He was moving up fast.

DeMay was watching Beauchamp lead and hoping his rider wouldn’t make a mistake that might cost him the National. Although he had won San Jose’s September thriller—a stunning go-round that saw Beauchamp and his ever-grappling teammates swap the lead amongst themselves 46 times—Rex had almost thrown it away in the final laps by somehow managing to run over and injure his own left foot with his back tire.

The boo-boo this time came when he allowed the charging Springsteen to pressure him off the shiny groove. At 115 mph, Beauchamp went into a wild skid in the third turn. By the time he’d fought his heavy bike back into control, Springsteen had passed and taken possession of a clear lead.

Although he was ranked third in the U.S. last year and was victorious in two prestigious half-mile Nationals, Springsteen is still a bit green to fully comprehend mile track tactics. Leading the race, his lap times mysteriously dipped by half a second, according to DeMay’s watch.

Sensing that victory was not an impossibility, Beauchamp became deadly serious, closing the gap on the less experienced Springsteen. He passed him on the next-to-last lap and won his second consecutive San Jose Mile. He’d only required 15:47.17 to do the 25 miles, which was his second record of the afternoon. Winning a 10-mile heat earlier, he’d slashed four seconds off the old standard.

Scott, Jorgensen on the heroic Norton, and Keener were 3rd, 4th and 5th, 10 seconds behind the winner. Sassaman pulled in 7th.

Then Scott claimed Beauchamp’s record-breaking engine and Babe DeMay had to unbolt it from its frame and hand it over.

DeMay had so many manhours in the engine that losing it must have been like losing a friend. But DeMay supports the claiming rule. “How else can a privateer keep up with the factories?”

“That’s all right, Cy,” said Nick Deliganis, tuner for Gene Romero, “You’ll just go back to Milwaukee and build another good one.”

“I guess so,” replied DeMay.

“Sure you will. Now let’s go drink some beer. Get a little sideways.”

DeMay nodded, smiled slowly. It seemed the best thing to do. In a few minutes he’d go drink that beer. But not

with Gary Scott. S

RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

AUGUST 1976 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

AUGUST 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

AUGUST 1976 -

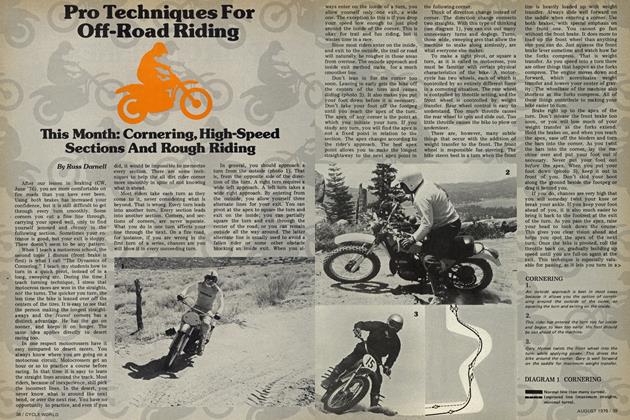

How To Ride

How To RidePro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

AUGUST 1976 By Russ Darnell -

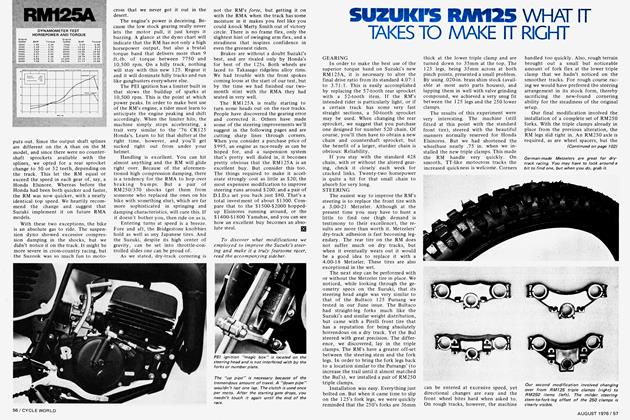

Special Test

Special TestSuzuki's Rm125 What It Takes To Make It Right

AUGUST 1976 -

Competition

CompetitionThe Story of Ow72,that Is.

AUGUST 1976 By Joe Scalzo