The Story of O...

KENNY ROBERTS is small in stature: barely five-feet-six and 137 pounds. But the most extraordinary motorcycle racers are often the smallest ones. . .and Yamaha International Corporation has the good sense to recognize that fact. Anything its undersized, overtalented and most valuable race winner wants seems to be his for the asking.

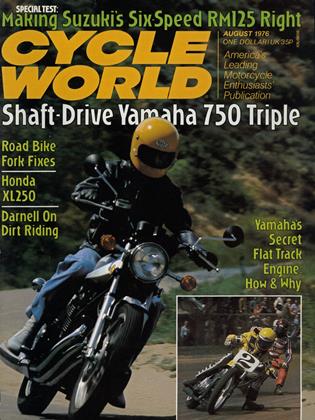

That’s an important fact to realize when one considers the amazing and still-continuing saga of a rare racing Yamaha called the OW72, whose strange debut occurred on the San Jose Mile some months ago. Kenny Roberts is crucial to the story, because if it hadn’t been for him, there’d be no OW72 Yamaha.

No one knows better than Roberts how much his sponsor loves pampering him. So when the U.S.’s highest-salaried motorcyclist asks for something, he wisely makes it a lot. Back in October, 1974, Roberts wanted Yamaha to buy him the exclusive services of one Tim Witham, a revered racing tuner from an earlier era. That time Kenny seemed to have asked for too much.

One person who thought so was Dick O’Brien. ‘T know Roberts is trying to get Tim,” remarked the omniscient race manager at Harley-Davidson, a long-time friend, admirer and racing rival of Witham’s. “But I doubt if he will.” The reason was that the 62-year-old Witham was out of racing. He was totally absorbed in his new company, S&W Engineered Products. Developing, massproducing and marketing sophisticated suspension kits for motocross and road competition took ail of Witham’s time.

Not that the quiet-spoken Witham wasn’t flattered by the Yamaha offer, you understand. Against his better judgment he was intrigued, as well. Witham regarded Kenny Roberts as one of the two most versatile racers he’d ever seen. The other one was the great Joe Leonard, Witham’s former rider. Like Leonard, Witham found, Roberts knew precisely what he wanted a motorcycle to do on a given track.

But Witham had already spent too many years racing—more than 40 in all. He’d had a bellyful it it. He did not want the traveling and the endless hours that went with the job, the frustrations and the galling losses that outnumbered the successes. Roberts—with helpful prodding from Yamaha’s national team manager and fellow Witham fan, Pete “The Godfather” Schick—persisted: Witham wouldn’t have to travel, and he wouldn’t have to stay up late bolting engines together or doing assembly work at all. Nor need he concern himself with Yamaha’s road race program, already splendidly handled by Kel Carruthers.

Instead, the gifted tuner was being called upon solely for the purpose of developing better and more powerful dirt track engines. Yamaha’s four-stroke 750 had long been the weak link in the factory race plan. The vertical Twin was eight years old. When originally conceived it developed 56 horsepower. Thanks to the dogged efforts of Shell Thuet and a few other faithful Yamaha men, the output had reached the 70s. But the dreaded XR Harley-Davidsons that it battled on mile and half-mile dirt tracks hovered in the 80s.

During 1974 Roberts and other Yamaha riders won four dirt Nationals Harley-Davidsons won six. At midseason Roberts and then-teammate Gene Romero complained that the factory bikes Shell Thuet gave them were no longer fast enough. That October Yamaha fired Thuet.

Joe Scalzo

“No matter what I did,” Thuet noted at the time, “those guys asked for more horsepower.”

Actually, Roberts liked and respected Thuet: “He did a super job.” But while Roberts and Pete Schick considered Thuet a dedicated journeyman, they believed Tim Witham was best equipped to perform the delicate, horsepower-producing development work they thought necessary.

Witham finally agreed and was signed to a lucrative contract. Part of the reason for his eventual assent was that he believed certain people in racing considered him a has-been, no longer able to cut it. Later he would say: “The worst thing someone can do is consider you a has-been. Then you really want to show them.”

From his S&W headquarters in Downey (just outside Los Angeles), he set to work. Witham didn’t really like the Yamaha dirt track engine. Unlike the XR model Harleys that Witham regarded with admiration and apprehension, the Yamaha wasn’t a pure racer and never would be. It was a warmedover street motor. Because of design limitations it was already stressed to the breaking point. And so, Witham somewhat ruefully pointed out, it wasn’t a development but a modification program that he was involved in.

“With an engine like this there’s only so much you can do,” he said, and began strengthening as many stress points as possible.

Six different versions of the engine saw the light of day during 1975. Modifications included beefed-up crankcases, strengthened gearboxes and clutches, updated connecting rods, valves, pistons. The two fastest engines were reputedly 10 hp stronger than any previous Yamahas. Roberts and 18year-old Skip Aksland sent them to a smashing one/two pasting of all the Harley-Daivdsons in the Ascot Park season finale.

Ascot was Roberts’ sixth Championship win of 1975’s Camel Pro Series. But he still hadn’t earned sufficient points to hold the Number One title he’d owned for two years. Number One had gone instead to the slower but more consistent Gary Scott. With the exception of those six wins, 1975 had been disastrous. Roberts’ dirt track Yamahas lacked the reliability they’d known when Thuet worked on them: a coil wire had shorted at Columbus; and at three different Nationals chains had blown off rear sprockets (including once when Roberts, showing some magical riding, had charged from last place into the lead).

All of the breakdowns made the often outspoken Roberts smolder. And after a ruptured gearbox caused him to miss Terre Haute in August, Schick, Witham and Bud Aksland, Roberts’ traveling dirt track mechanic, were to feel the full force of the Champ’s anger.

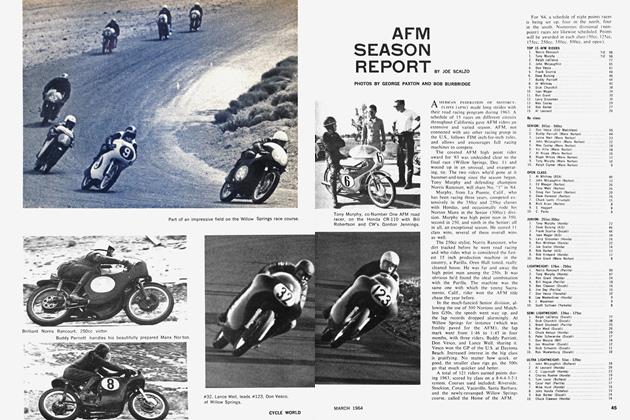

Roberts shipped all of Witham’s four-stroke Yamahas back to California, then had Schick instruct Kel Carruthers to build him “a rocketship” for the upcoming mile track meet at the Indianapolis Fairgrounds. Using one of the overpowered TZ750 two-stroke road racers, Carruthers actually had a machine together in 10 days. Still angry, Roberts promptly stormed it to the most savage and hair-raising victory of the season and his life.

But the four-cylinder beast proved unridable at Syracuse and San Jose and was ultimately banned from further competition.

Mechanic Bud Aksland, Skip’s older brother, shouldered much of the blame for Roberts’ numerous breakdowns. It wasn’t particularly fair, since all Aksland had done was bolt the pieces together, but he stoically accepted it nonetheless. He wanted Roberts to win as badly as everyone else did. And all Kenny needed to win, Aksland believed, was the horsepower to nail the runaway Harley-Davidsons when firing off the turns, and then to pull abreast of them on the straightaways. If Kenny could do that, he could battle the Milwaukee bikes on equal terms in the comers. Any time that happened, Aksland was convinced, Roberts would have the advantage.

But Aksland didn’t know where that mythical horsepower would come from.

Tim Witham dismissed the numerous breakdowns as “teething problems,” and faulted the shortage of time. He’d started the Yamaha project with the ’75 season almost underway. He’d never made up for his late start. Besides doing Roberts’ engines, he’d also gotten into the frames and suspension systems. Simultaneously carrying out muchneeded development work in all three areas had been wearisome. Witham further noted that it took longer to get things built than it had in the old days.

Noticeably left unsaid.by all hands was that Kenny Roberts had personally erred several times. The dethroned Champion had organized his dirt track program during ’75, and his organizational abilities hadn’t equaled his riding ones. Costly, too, had been the Yamaha star’s tactical blunder at Castle Rock when he’d spilled and lost a National he should have won.

More bad news loomed ahead. True, 1975 had ended with the heartening rout of the Harley-Davidsons at Ascot. But the 750 Yamaha had hit its horsepower peak in order to achieve it. That was the trouble. Little more of significance could be done to improve it now. Meanwhile, Dick O’Brien’s formidable 1976 orange-and-black models were certain to be faster than his ’75s.

The basic problem with the Yamaha dirt track engine was a big one. The production cylinder head simply couldn’t “flow enough air.” With more slippery intake ports and valves (like those in the XR Harley-Davidsons, for instance), great performance gains might still be made, according to Witham. But, because of the built-in shortcomings of the cylinder head, not much could be done to the Yamaha.

Ideally, Witham wished Yamaha would create an entirely new cylinder head—one with radically different exhaust and intake valve angles and larger ports. With such a head, and other refinements, Witham could get perhaps 90 horsepower, putting the Yamaha in the Harley league at last. Without it, there wasn’t a prayer. But Yamaha would never go to that much trouble and expense.

Or would it? Astounding as it sounded, it seemed that, yes, Yamaha would. The result would become known as the OW72.

Pete Schick could scarcely fathom it, and the Yamaha race manager had been in on the far-fetched project from the start. That start had occurred in July, 1975, a few days after Roberts’ Columbus debacle and a couple of weeks before the upcoming one at Castle Rock. Schick, Roberts and Kel Carruthers all jetted to Japan and Iwata City, main headquarters of the Yamaha Motor Company. Roberts and Carruthers were to spend 10 days checking out the latest road race equipment. Schick, meanwhile, sat in on various meetings, several of them with an eightmember engineering team headed by Chief Engineer Tanaka, Yamaha’s foremost four-stroke engine designer.

The overstressed 750 dirt track engine was mentioned during the meetings. Using an interpreter, Schick told of the advanced state of development the engine had achieved through U.S. racing efforts. He received an interested response. The more Schick talked, the more interest was shown. But when the race manager mentioned the drawbacks of the eight-year-old cylinder head, he drew a sympathetic reaction.

Then Schick pulled out some blueprints and mechanical drawings Witham had given him. The drawings were of a redesigned cylinder , head that could be bolted atop the engine’s existing cylinders and crankcases.

To build the molds and castings for producing a cylinder head would have been prohibitively expensive in Amer ica, far beyond Schick’s normal racing budget. Would the factory, he wondered, undertake it. . .even for Kenny Roberts? Probably no factory in racing history had ever gone to such pains for a racer. Schick doubted that Yamaha would be the first.

The engineers wanted to know how many cylinder heads would have to be built.

Surprised by this response, Schick answered: just 24.

The engineers went into a huddle. They came out of it wIth the decision to undertake the project.

Timing, it seemed, was just righ Famous for its two-stroke, Yamaha had recently taken a keen general interest in four-stroke engines. Building the new cylinder head could later provide invaluable feedback for the mass-production of future four-stroke motorcycles.

But perhaps the real reason for the thumbs-up was that, in Japan as in America, everyone wanted to give the valuable Roberts exactly what he wanted and deserved.

Schick broke the great but unex pected news to Roberts and Carruthers~ who had just successfully wrapped up their road tests. On the 13-hour flight home they talked about it non-stop. Everyone was pleased. Even the usually reserved Witham seemed impressed when Schick told him.

For the rest of the summer Telex messages, telephone calls and cable grams shot back and forth between Iwata City and the Yamaha International Corporation in Buena Park, Calif. The project was intentionally shrouded in secrecy. U.S. engineering head Mack Suzuki and his assistant Keith Emi made the necessary translations from English to Japanese and vice versa. In Japan, the engineers performed some incredibly fast footwork. Only three months after his original meeting with them, Pete Schick had the first raw cylinder head casting on his desk.

Looking at it, perhaps realizing for the first time that the unprecedented project was really going through, exhilarated Schick. The new cylinder head was finally close enough to reality to be christened OW72.

Now Schick could plan ahead. From now on, he explained, everything had to be done exactly “by the book:” the racing rule book of the American Motorcycle Association.

Twenty-four OW72 cylinder heads— no less—had to be produced. Not only that, they had to be part of 24 complete engines. Nothing else would satisfy the Professional Rules Committee. Should Yamaha get caught attempting to bend the rules to have its OW72 approved (“Doing something shady,” was Schick’s description), the negative publicity could wipe any expected race successes,

Schick, in fact, was acutely concerned with Yamaha’s—and his own“funny position” with the OW72 and all of their racing. It was why he’d kept still when the TZ750 four-cylinders had been banned from AMA dirt track competition. Even though Schick believed the banishment unfair, not to> mention technically illegal, he’d dared not protest too loudly. If he had, it might have appeared that Yamaha was rigging the rules to its own advantage so that the factory might dominate competition.

Now it was October, 1975. Eight months away was the OW72’s planned debut at San Jose on the blazing-fast Santa Clara Fairgrounds mile track. The annual California race is regarded as the pro tour’s classic dirt event. Eight months seemed like ample time—more than half a year. Considering all that still had to be done, it was no time at all.

One thing was sure. Yamaha certainly was going to lots of trouble for Kenny Roberts. The factory wanted to see its pet rider—and its only fullysponsored one—with his hands once again on the Number One plate by the end of the ’76 season.

Of all the key personalities involved in the OW72 project, none was more harried than Kel Carruthers. In his garage he was busy assembling steeplechase bikes for Roberts and Skip Aksland for the year’s opening National at the Houston Astrodome, as well as looking ahead to the Daytona road race in March. For 1976 the drawling former World road race Champion from Australia was in charge of all Roberts’ bikes, dirt and road. He had his overworked staff of six going flat-out. All-new and exceedingly trick dirt track frames, designed specifically for Roberts by race car engineers Trevor Harris and Bruce Burness, and built by the C&J company, had recently been trucked to desolate Turlock in the state’s center. Turlock was where Roberts maintained a winter residence at his in-laws’ farm. Piloting a farm tractor, Kenny had burrowed out his own special dirt test track.

Slowly the OW72 project moved ahead. It was a desperate plan, but also an imaginative one. Roberts, in particular, was determined that it succeed. Shortly after New Year’s he jumped into a car and barreled out of Turlock to Southern California, where he berated everyone in sight for what he perceived to be unnecessary delays. Bitingly reminding Schick, Witham, Carruthers and Bud Aksland that San Jose wasn’t that far off, he then took off in the opposite direction for Turlock and continued frame testing on his track.

From no other rider would the four men have taken talk like that. But this was Kenny Roberts. And one look at the recently-released race schedule revealed the real reason for his outburst. Twenty-four of 1976’s record 28 points-paying Nationals were on dirt courses of one configuration or another. To beat the Harleys on such tracks would take a strong engine.

The new cylinder heads began arriving in twos and threes from Japan, with Schick passing them right along to Witham. They had no ports, valve seats, guides, camshafts, valve springs, etc. Everything had to be built. And the heads still had to be flow-tested, ported and polished. That wasn’t all. Witham had a score of companies and gifted individuals busy on improved pistons, connecting rods and gearboxes. He was getting bigger crankshaft pins too. If time didn’t run out first, this was expected to be one choice engine.

By now, the ’76 season had begun. Using a year-old engine on the dirt floor of the Houston Astrodome, Roberts finished 2nd in the Steeplechase opener. The Yamaha hero proclaimed himself dissatisfied with the handling of his new C&J frame, however. It had terrific potential, but needed more testing.

Daytona in March got in the way of those tests. Roberts went to the annual road race heavily favored as always. He should have won going away, but instead was lucky to ride out a flat tire at 155 mph. The experience temporarily sobered him, although good things were happening to him too. He’d just purchased a silver Mercedes 450SL, plus a new home back in Modesto. To friends he confided that his wife Pat was expecting the couple’s second child.

While at Daytona, Roberts encountered Hank Scott, Shell Thuet’s latest rider, and a feared if youthful contender on dirt. Seeing Roberts, the ebullient 21-year-old crowed: “Shell’s promised me so much horsepower at San Jose that no Harley’ll even be able to get in my draft.”

Plainly, Roberts, Schick, Witham and Carruthers weren’t the only Yamaha hands with big plans for San Jose’s Mile.

But whatever was going to happen would be soon. San Jose was barely two months away. Inexplicably this was when a maddening rash of seemingly unrelated problems began striking down many of the OW72 project’s principals.

Arriving home from Daytona, Tim Witham fell ill. He was bed-ridden with flu for a couple of weeks. One of the few truly health-conscious individuals in racing, no one could recall the last time Witham had been sick. But he was now.

Concerned as he was about Witham, Pete Schick was equally worried about the deteriorating health of his star performer. Since returning from Florida, Roberts seemed run-down and pale. Schick wished Roberts would rest himself before San Jose. Instead Roberts and Kel Carruthers were jetting to the International road race at Imola on April 6th.

Schick had selfish reasons for not wanting Roberts to set wheels on the high-speed Italian track. One spill over there, one injury, and Roberts could miss San Jose. That would be catastrophic. Without Roberts to ride it, there was little point in completing the OW72.

While Roberts’ Italian-bound 747 was touching down in Milan, Skip Aksland, Yamaha’s unsalaried test rider, was preparing to race one of the team dirt trackers at Ascot Park that Friday night. And Pete Schick was driving to Hangtown near Sacramento. Sunday was to see the debut in National competition of Yamaha’s young motocross team on new water-cooled models.

At Hangtown, Schick found himself thinking about the OW72 instead of the motocross. One of Yamaha’s kid riders, Bob Hannah, 18, sped to a dazzling victory. Afterward, Schick saw and talked briefly with Dick O’Brien. O’Brien was there to direct HarleyDavidson’s motocross team. His mind was on the upcoming San Jose tilt too. “Lots of problems before San Jose, getting our new XRs running with mufflers,” O’Brien groused to Schick. Mufflers were mandatory in ’76. Schick nodded sympathetically. O’Brien didn’t ask Schick about the new Yamaha, although Schick was certain the HarleyDavidson chief knew about the OW72. He knew everything else.

Schick returned to his office Monday. Disaster awaited him on all fronts. Roberts had seized an engine and crashed at Imola. How was Roberts? Okay, but with a badly sprained left ankle, was the only report.

Schick winced. The next Camel Pro Series National was Saturday night’s Short Tracker at Texas Stadium in Dallas, where Roberts would need a strong left ankle for cornering.

Skip Aksland was semi-conscious in the intensive care ward at Harbor General Hospital. He’d taken a hard fall at Ascot and was badly chopped up. Another motorcycle had unavoidably run over him on the track. The teenager would live, but could do no racing for at least two months.

With Aksland hurt, it meant that the more valuable Roberts would be pressed into extra duty testing frames and engines prior to San Jose. And Roberts had a sprained ankle!

Worse, like Witham, he had flu. He’d picked it up in Italy. Or perhaps it was something really bad, like hepatitis, as one doctor he’d gone to feared. In any case, when Roberts arrived back in Calif, he was limping, paler than usual, and in a prickly mood. Mainly he was perturbed that his pal Aksland had been permitted to race at Ascot on the same motorcycle that Roberts had himself considered out-of-whack at the Houston Steeplechase. Kenny stolidly left for the Dallas Short Track on crutches. He won, of course. He didn’t become Kenny Roberts for dogging it at times like this.

Roberts had no time to savor the moment. Instead, he boarded another 747 to meet Kel Carruthers in England the following weekend and head the U.S. road team in the annual TransAtlantic Match Races. He shrugged to an ever-anxious Pete Schick that British promoters had offered starting money so astronomical he couldn’t refuse.

Back in Southern California, deadlines that had earlier seemed so feasible for the OW72 project were long past. February was to have marked the new engine’s first runs on the dynamometer. But not until April 14 did a completed engine actually fire. It occurred in the dyno room deep inside Yamaha’s corporate buildings. Bud Aksland had just finished bolting everything together the day before. His only company in the room was a big wooden clock ticking loudly on the wall. For an hour and a half Aksland ran the roaring engine up and down the power scale. Next he computed horsepower Figures with a pocket calculator. They exceeded all previous Yamaha records.

Buoyed by the Figures, everyone’s spirits lifted. Witham had thrown off his flu and was needed back on the job. Powerful as it was, this engine lacked the latest pistons, camshafts and so forth. But the news from England a couple of days later wasn’t good: Roberts had taken one spectacular fall and a second Firey one. He’d suffered bumps and second-degree forearm burns.

Ten days later, on April 28, a Wednesday, Roberts—battered, black and blue, but safely home againclimbed into his 450SL and raced 400 miles south from Modesto to San Diego and Carruthers’ headquarters. He spent a full day lapping ’round and ’round the nearby South Bay Speedway dirt track. He was testing the new C&J race frames in place of the still-injured Skip Aksland. Afterwards Roberts seemed pleased, but suggested some subtle changes. Despite his English burns and Italian ankle, he was looking relatively fit again. He’d consulted another doctor. This one had assured him he didn’t have hepatitis after all.

The tempo was picking up as San Jose neared. That same day, just 100 miles to the north in Buena Park, a passenger car pulled up in front of the Yamaha International Corporation. Out of it stepped Professional Rules Committee member Earl Flanders, an AMA technical inspector of 28 years experience. Pete Schick had called him in on official business. The OW72 was at last ready, as Schick put it, “for the count.” Flanders opened his official competition rules book to the page that read:

“/n order to be approved, a motorcycle must be a standard catalogued production model, one complete motorcycle produced, race ready, and at least 24 identical engines and transmissions must be available for inspection and purchase within the United States. ”

Schick escorted Flanders to a rear room. Inside, all seemed in order. Flanders counted 24 vertical twincylinder engines neatly lined up, and another one cradled inside a street Yamaha complete with headlight.

Flanders was impressed with the orderliness and tidiness of the operation. Plainly, Schick was still playing it “by the book.” But Flanders wasn’t aware of the headaches it was costing Schick. To get the 24 engines together in time, Schick had had to borrow three mechanics from the Snowmobile Division of Yamaha and put them to work in relays. For two weeks the mechanics had unbolted and removed normal cylinder heads from normal street engines and replaced them with OW72 cylinder heads.

Flanders spent two hours on his inspection. He had mechanics take apart some of the engines so he could see that the cylinder heads were complete. He kickstarted the street motorcycle to prove that the OW72 actually ran. Flanders was conscientious and thorough. Schick stood by at all times, unflappable when it came to answering questions.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 71

Done, Flanders thanked Schick and left to complete his report. It would be submitted to the Professional Rules Committee at its May 4-5 meeting in Westerville, Ohio. The OW72 still had to be approved officially, but that was a mere technicality now.

None of the 24 engines Flanders had so studiously inspected were the ones Kenny Roberts would race. Those engines, with special pistons, cams, etc. were still being completed. The special parts were rolling off milling machines and presses daily now. Time was short, though. Plans to have six hot engines ready for San Jose had been scrapped following Aksland’s ill-timed Ascot fall. Now Tim Witham would be satisfied with three.

Picking up the various parts as they were completed by the various contractors was Bud Aksland’s job. His schedule was as hectic as anyone else’s in the OW72 project. A typical day might find Aksland at Sig Erson’s cam shop in Gardena in the morning, at Forged True Pistons in Santa Fe Springs that noon, over to C.R. Axtell’s in Glendale for flow-tested cylinder heads in the afternoon, and then to Pete Smiley’s machinist works for freshly machined crankcases in the evening. The highpowered names revealed the talent involved. Afterward Aksland might haul all the pieces to Kel Carruthers in San Diego for careful assembly. Some weeks Aksland drove his pickup truck 1500 miles or more on the Los Angeles area freeways.

More dynamometer runs were scheduled, then scrubbed. Tests originally set for April 29 didn’t actually happen until Thursday, May 6. At that point San Jose was less than two weeks off.

Inside the dyno room stood Schick, Witham, Bud Aksland, a Yamaha employee named Bill Stewart, and Art Lamey from Champion Spark Plugs. The blood-boiling bellow of the OW72 at 8000 rpm almost blew the roof off the joint.

The tests of two completed engines were extensive, continuing for several days. New camshafts, pistons and other parts that arrived in the middle of testing were fitted and checked out. At one point, horsepower figures mysteriously dropped by four. A temporary panic erupted. Stemming it, Witham said: “That’s the way it goes with a new engine. You may break through a problem in an hour. Or you may break through in a week. We’ll beat this one.”

Apparently they eventually did. Later the hot engines were removed from the dyno, trucked to Carruthers’ place in San Diego, and bolted into frames. On May 9 they arrived at the deserted Santa Clara County Fairgrounds. Roberts, whose home is not far from San Jose, had used his enormous influence to rent the mile track for testing.

Waiting with Roberts at San Jose was a surprise—Skip Aksland. A remarkably fast healer, the youngster had passed the weeks following his Ascot crash swimming and exercising at his parents home in Manteca. His one bad shoulder felt strong again, although the doctor at first refused to give him the okay to race: “Your shoulder is still weak, and if you fall, you’ll hurt it again.”

Thinking about San Jose’s 120-mph speeds, Aksland had thoughtfully replied: “If I fall, I’ll hurt it anyway. It won’t matter how strong it is.” He got the doctor’s required signature.

The closed tests lasted that Monday from nine in the morning until three in the afternoon. The track didn’t have a groove laid down and was unseasoned. Only Witham, Carruthers and a few other intimates were there to watch. Pete Schick wasn’t among them. Sitting in his office, he nervously wondered how things were going, and whether or not the OW72 engines and race frames had been adjudged successful. Late that afternoon Schick got the telephone call he’d been waiting for. It was from Kenny Roberts.

“All I can say about those new dirt bikes, Pete, is. . . .”

“Yes?” Schick waited.

“They’re a hundred percent better than last year’s. Yeah, Skip and I got ’em running pretty fast today.”

Schick was elated. Those were the first positive words Roberts had spoken in months. But the star rider couldn’t resist a final dig at his team manager.

“It’s about time, too,” Roberts said before hanging up.

From San Jose, the race engines were trucked back to Yamaha’s dyno room for yet another round of testing. Time was so short that the plan to build three entire engines had been changed to two. Whichever one Roberts didn’t want, Skip Aksland would get.

The final dyno runs took place on Friday, May 14, less than 48 hours before the race. The OW72’s full potential had yet to be realized. But time had temporarily run out.

“We’re done for now,” Schick said. “We can’t do research and development forever.”

He had a point. The number of manhours so far consumed by the OW72 project must have been unbelievable. Asked to estimate the figure, one person close to the project replied: “Don’t ask. Just like anything else in racing, it’s more than you want to think about.”

As for the total cost in dollars, that was another story. Either no one knew, or no one would say. One person not directly connected with the project guessed $50,000 per engine. “No, not that bad,” Schick said. “Cheaper in fact than I thought it would be.”

Just that morning Schick had received confirmation that the eight factory engineers he’d had his original meeting with, including Chief Engineer Tanaka, would be flying across the Pacific to San Jose specifically to witness the May 16th meet. They wanted to see what the OW72 could do. Schick hoped that Kenny Roberts would give them a good show.

there are fairy are stories. racing The stories difference and there is that fairy stories always have happy endings. Racing stories frequently don’t. The end of this story is sadder than most.

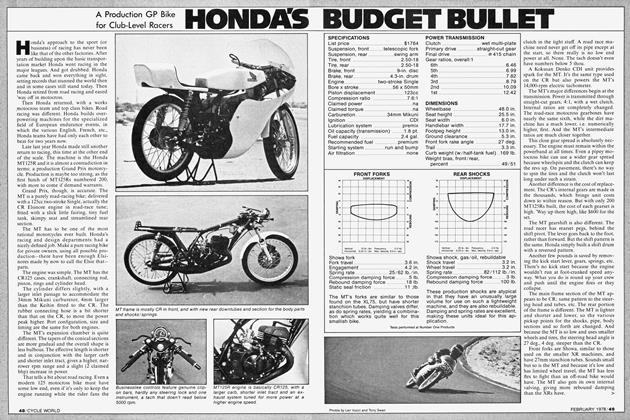

Sunday, race morning in the crowded and noisy San Jose pits in the infield of the mile track, the twin OW72s attracted no special attention. To the uninitiated, they looked like any other Yamahas, although—typical of Carruthers’ hand—they were nicely turned out and immaculate in appearance.

Then it happened. Pete Davies, a veteran member of Carruthers’ staff, was standing beside one of the bikes. Bill Werner walked over wearing his familiar orange-and-black Harley-Davidson colors. Last year’s star tuner for Gary Scott was now working with Jay Springsteen.

Davies and Werner smiled and chatted. “Bike sure looks nice,” complimented Werner. Then he pointed toward the supposedly-secret OW72 cylinder head and asked; “How do you think your new heads will work? I mean, raising the inlet angle and all?” Davies could not resist smiling. As usual, the Harley guys were well-informed.

Schick and Dick O’Brien were shaking hands elsewhere in the pits. “I thought you’d be going to another motocross somewhere instead of coming here,” remarked O’Brien, tongue-incheek.

“No way,” Schick smiled.

O’Brien rejoined: “I know. I’m like you. I wouldn’t have missed this one for the world.”

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 89

Kenny Roberts materialized, his tiny forearms still bearing signs of the English burns. Unsmiling, he climbed aboard one of the Yamahas. Schick, Witham and Carruthers watched closely. The moment they had awaited so long was almost at hand. The engine fired and Roberts rode onto the bone-hard dirt track for practice speed runs with the rest of the pack.

Rarely before had so many eyes, not to mention stop watches, been directed toward a single rider. As many of those eyes belonged to Harley-Davidson personnel as to Yamaha people.

No one could believe it. Roberts’ opening laps around the mile were down in the 38-second range—at an average of nearly 95 mph. Only one of the many Harley-Davidsons on hand was as swift.

The times were fast, but without a pronounced verdict from Roberts, they meant little. Roberts braked the bike to a stop in the pits and Carruthers awaited him, the anxious look in his eyes.”

“Best thing I ever rode,” mumbled Roberts, or words to that effect, as he headed toward the second Yamaha, anxious to get his hands on it, as well. This one turned out to be his favorite; it handled better and seemed to accelerate faster than the first one, which was immediately consigned to a waiting Skip Aksland.

As San Jose’s corners began turning black and slippery from accumulated rubber, Roberts’ lap times plummeted. And when he qualified, he was going two seconds slower than when he’d practiced. Something was seriously amiss.

It didn’t seem to be the engine, which appeared to have the power to run with the three leading HarleyDavidsons and Hank Scott’s Yamaha in Roberts’ ten-lap qualifying heat. It was a problem of traction. Slewing wildly in the turns, Roberts had the Yamaha so sideways he was losing time getting horsepower anchored to the track. He was lucky to dispatch Scott’s rival Yamaha on the last lap, the pass that put Roberts in the National.

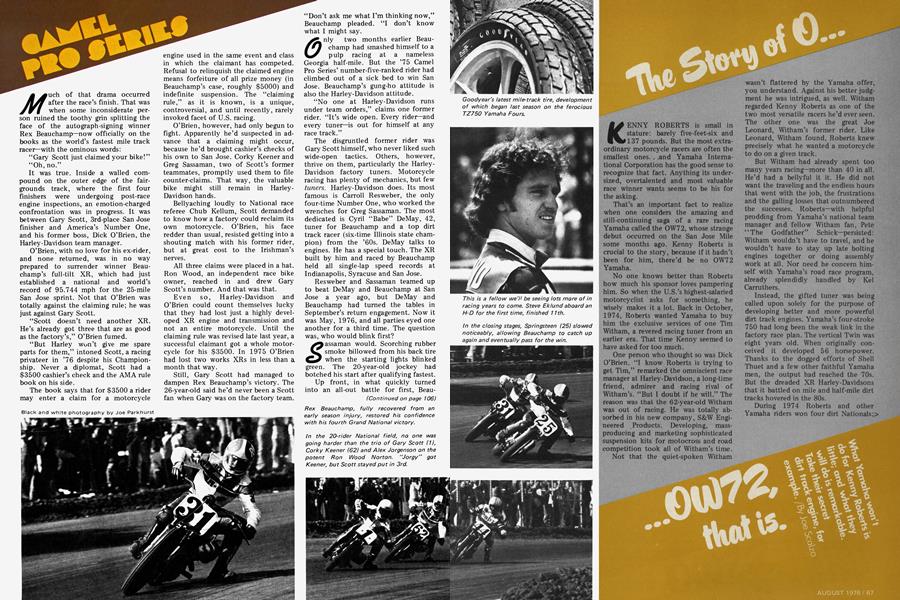

What was the matter? Perhaps it was the all-new Goodyear tires everyone was having trouble becoming accustomed to. More likely it was in the highly-sensitive race frames that had to be finessed just right to work. So much time had been consumed over the past eight months by the engine, time had run out to fully perfect the frames.

Which was the real irony: apparently the OW72 was a powerful engine, perhaps even a great engine. But, because of the spinning tires, it couldn’t flex its muscles to prove it.

Carruthers and his men changed the front and rear suspensions, they swapped the gearing so that Roberts could race in fourth gear instead of fifth. They struggled away as the broiling San Jose sun baked their bodies pink. They just had things back together again in time for the 25-mile National.

Perhaps Roberts could still win. He’d overcome problems before and somehow managed to. Only the OW72 engine refused to start. It wouldn’t start even as the loudspeaker system warned that the race would begin without Roberts if the bike wasn’t delivered to the starting line immediately. Finally Carruthers got it going. But on the starting line it died again. And as Carruthers fretted and fumed with the wiring system, the National roared away. And Roberts sat on his dead motorcycle watching it go.

Harley-Davidson wound up taking nine of the first 10 places.

Somehow a coil wire coupler above the engine had failed. It might have vibrated and broken itself during Roberts’ heat race. A two-cent item had wiped out eight months of effort. It seemed enough to reduce even hardened professionals to frustrated tears. Only there were no tears.

Tim Witham glumly tightened his suede coat around him, as if suffering from chill. But the temperature was in the 80s. He didn’t say much.

Carruthers was gesturing with his hands and speaking in pidgin English to Chief Engineer Tanaka and his aides: “Bike work very good when track is tacky, yes? But when track change, bike no handle. We fix, though.”

Kenny Roberts was changing from his still-clean racing leathers into street clothes. He was signing autographs. He didn’t seem depressed or angry, merely resigned. He exchanged opinions with Skip Aksland who had come agonizingly close to putting the second Yamaha in the field, but failed.

Roberts said, “I feel sorry for our guys, all the work they went to for this race. Can you imagine? They even went to all the trouble of building 24 of these things. But it’s good, though. Lots of potential in that bike. I’m pleased. Once we get those frames right, we got ’em.”

With wife Pat and son Kenny Lee he walked toward his Mercedes. Then, he was gone. Pete Schick glanced around quickly when someone called his name. As usual, the race manager was wearing dark glasses that shielded his emotions. He seemed tired and let down. Suddenly he shrugged and smiled briefly. What the hell. He’d tried.

All of them would keep trying for the balance of the season until they had the OW72 spot-on. There was no question that they would ultimately get it right, either. They had to. Kenny Roberts was riding it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

AUGUST 1976 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

AUGUST 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

AUGUST 1976 -

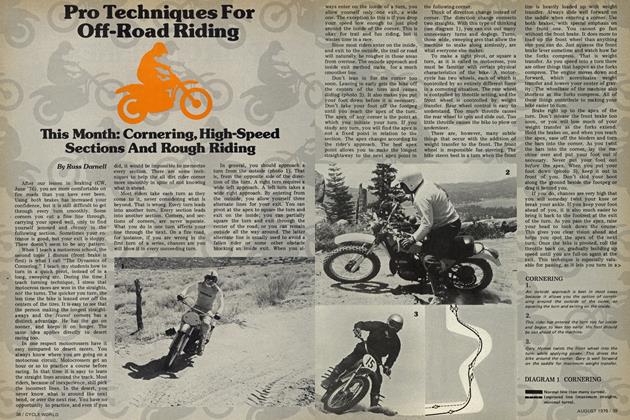

How To Ride

How To RidePro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

AUGUST 1976 By Russ Darnell -

Special Test

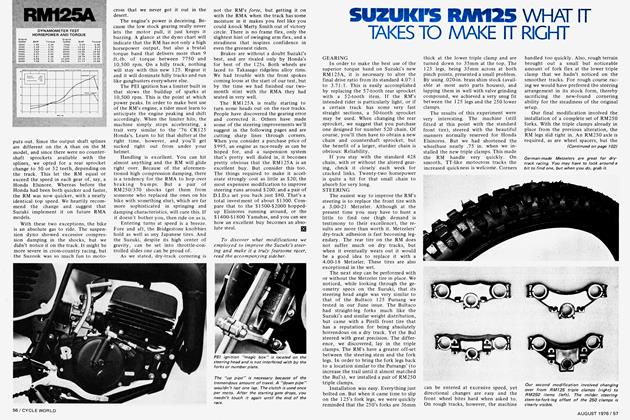

Special TestSuzuki's Rm125 What It Takes To Make It Right

AUGUST 1976 -

Competition

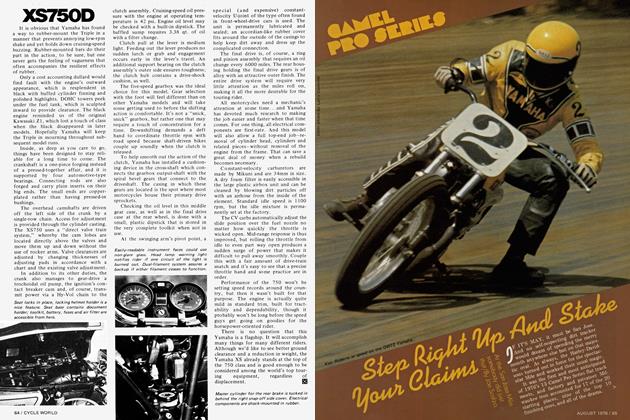

CompetitionCamel Pro Series

AUGUST 1976