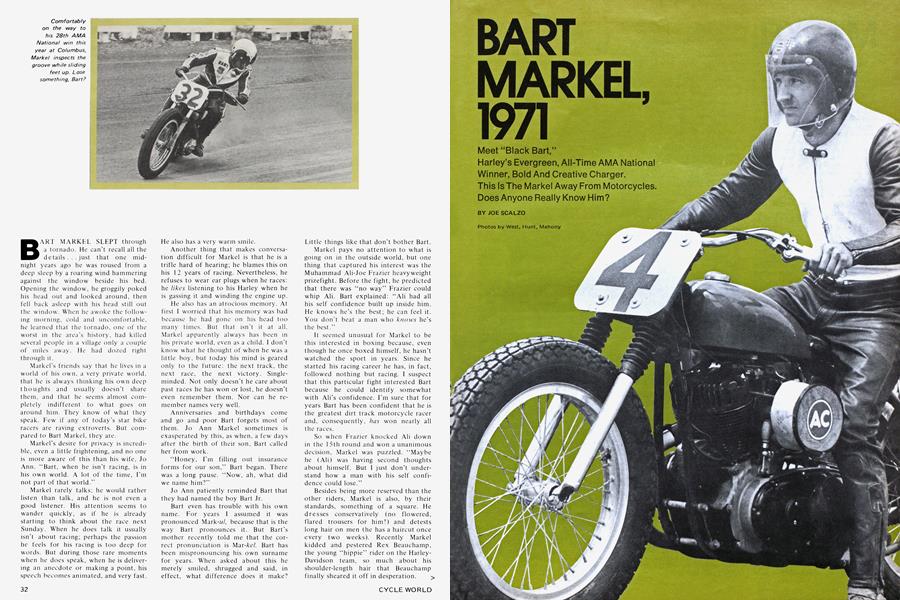

BART MARKEL SLEPT through a tornado. He can't recall all the details . . . just that one midnight years ago he was roused from a deep sleep by a roaring wind hammering against the window beside his bed. Opening the window, he groggily poked his head out and looked around, then fell back asleep with his head still out the window. When he awoke the following morning. cold and uncomfortable, he learned that the tornado, one of the worst in the area's history. had killed several people in a village only a couple of miles away. He had dozed right through it.

Markel’s friends say that he lives in a world of his own, a very private world, that he is always thinking his own deep thoughts and usually doesn’t share them, and that he seems almost completely indifferent to what goes on around him. They know of what they speak. Few if any of today’s star bike racers are raving extroverts. But compared to Bart Markel, they are.

Markel’s desire for privacy is incredible, even a little frightening, and no one is more aware of this than his wife. Jo Ann. “Bart, when he isn't racing, is in his own world. A lot of the time, I’m not part of that world.”

Markel rarely talks; he would rather listen than talk, and he is not even a good listener. His attention seems to wander quickly, as if he is already starting to think about the race next Sunday. When he does talk it usually isn't about racing; perhaps the passion he feels for his racing is too deep for words. But during those rare moments when he does speak, when he is delivering an anecdote or making a point, his speech becomes animated, and very fast. He also has a very warm smile.

Another thing that makes conversation difficult for Markel is that he is a trifle hard of hearing; he blames this on his 1 2 years of racing. Nevertheless, he refuses to wear ear plugs when he races: he likes listening to his Harley when he is gassing it and winding the engine up.

He also has an atrocious memory. At first 1 worried that his memory was bad because he had gone on his head too many times. But that isn't it at all. Markel apparently always has been in his private world, even as a child. 1 don’t know what he thought of when he was a little boy, but today his mind is geared only to the future: the next track, the next race, the next victory. Singleminded. Not only doesn't he care about past races he has won or lost, he doesn’t even remember them. Nor can he remember names very well.

Anniversaries and birthdays come and go and poor Bart forgets most of them. Jo Ann Markel sometimes is exasperated by this, as when, a few days after the birth of their son, Bart called her from work.

“Honey, I’m filling out insurance forms for our son,” Bart began. There was a long pause. “Now, ah, what did we name him?”

Jo Ann patiently reminded Bart that they had named the boy Bart Jr.

Bart even has trouble with his own name. For years I assumed it was pronounced Mark-ul, because that is the way Bart pronounces it. But Bart’s mother recently told me that the correct pronunciation is Mar-kel. Bart has been mispronouncing his own surname for years. When asked about this he merely smiled, shrugged and said, in effect, what difference does it make? Little things like that don’t bother Bart.

Markel pays no attention to what is going on in the outside world, but one thing that captured his interest was the Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier heavyweight prizefight. Before the fight, he predicted that there was “no way” Frazier could whip Ali. Bart explained: “Ali had all his self confidence built up inside him. He knows he’s the best; he can feel it. You don’t beat a man who knows he’s the best.”

It seemed unusual for Markel to be this interested in boxing because, even though he once boxed himself, he hasn’t watched the sport in years. Since he started his racing career he has, in fact, followed nothing but racing. I suspect that this particular fight interested Bart because he could identify somewhat with Ali’s confidence. I’m sure that for years Bart has been confident that he is the greatest dirt track motorcycle racer and, consequently, has won nearly all the races.

So when Frazier knocked Ali down in the 15th round and won a unanimous decision, Markel was puzzled. “Maybe he (Ali) was having second thoughts about himself. But I just don’t understand how a man with his self confidence could lose.”

Besides being more reserved than the other riders, Markel is also, by their standards, something of a square. He dresses conservatively (no flowered, flared trousers for him!) and detests long hair on men (he has a haircut once every two weeks). Recently Markel kidded and pestered Rex Beauchamp, the young “hippie” rider on the HarleyDavidson team, so much about his shoulder-length hair that Beauchamp finally sheared it off in desperation. ;

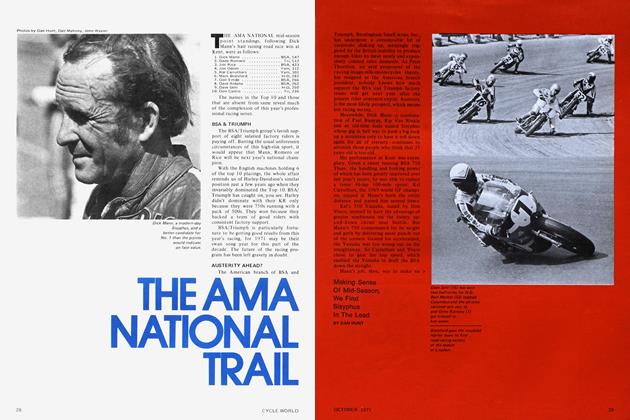

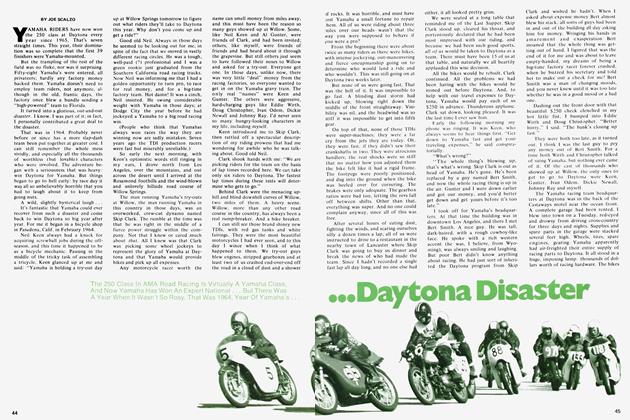

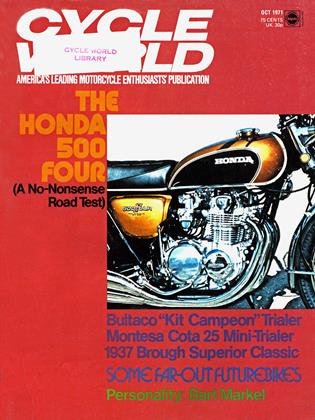

BART MARKEL, 1971

Meet "Black Bart," Harley's Evergreen, All-Time AMA National Winner, Bold And Creative Charger. This Is The Markel Away From Motorcycles. Does Anyone Really Know Him?

JOE SCALZO

Markel’s tastes seem somewhat on the bland side. When he goes to a movie, which happens very rarely, it will be a Walt Disney film or a western. He has never seen an X-rated show and has no plans to. Last February when he went to Lake Tahoe to race a snowmobile, he attended one of the bare-chested musicals at the King’s Castle for the first time and yawned his way through it.

He’s pretty much a hamburger-andfrench-fries man, avoids fancy restaurants and drenches nearly everything he eats in catsup. His coffee, after copious amounts of cream and sugar, looks (and no doubt tastes) like some kind of malt. Other than drinking coffee, he swills down Cokes. He drinks hard liquor only sparingly, and has never smoked cigarettes.

Like most bike racers, who have to work hard for their money, Markel is thrifty. And because he is Bart Markel, and in his own private world, he has never taken the trouble to learn how to write out a check. Jo Ann manages most of the finances in the Markel family, although Bart is no one’s fool in matters of money. After checking in at the King’s Castle for the snowmobile race, he went to his room, unpacked, and discovered he had forgotten to bring along any underwear. Downstairs in the men’s store of the swank hotel he grabbed a handful of underwear at random and the cashier began ringing them up at prices that, to Markel, seemed exactly double what he would have been charged at a regular department store.

Bart gathered up the parcels and put them back, saying hotly, “I'll go without underwear before l pay prices like that.’’

He feels uneasy when someone is paying his way and would rather do it himself. The hard-crashing Fvel Knievel, one of Markel’s friends, took Bart and Jo Ann out for dinner one night in Daytona Beach and insisted on picking up the tab. Later, after they had an after-dinner drink, Knievel picked up that bill too; he was on an expense account, he explained, and could well afford it. But Markel was uncomfortable about it all the same, feeling that he was sponging off Knievel.

The Markeis live in Flint, an industrial suburb of Detroit, where they own their own home. Bart was born in Flint. Occasionally he says he would like to move out to California but usually adds that he thinks Californians live too fast for him, and he wouldn’t be able to keep pace. A couple years ago he bought some land in Florida and someday, when his son and daughter grow up, he and Jo Ann may go there to live.

None of his neighbors in Flint know him well. Bart privately suspects that they all think of him as “that crazy guy who races motorcycles.” Of course he doesn’t give a damn what his neighbors think.

Some full-time racers literally desert their families at the start of each new season, leaving home for months on end, only coming back when they are out of money or their bikes have blown up. Not Markel. Most of the time he takes his family with him to the races. And after a Sunday race he is always back in Flint on Monday, ready to go to work. Since he started racing he has always held down an outside job of some sort, even when he was No. 1, and most of the time it has been with AC spark plugs. The reason he has to work, Bart explains soberly, is that the money he has made racing has never been enough to support him.

Today he works at the AC headquarters near his home, eight hours a day, five and six days a week as a tool and die maker, operating lathes, mills, and grinders. When 1 told him this did not seem a particularly glamorous job for one of the greatest racers in motorcycle history, and asked him why he didn’t get something more lucrative, or something more closely related to racing, Markel merely shrugged disinterestedly.

“1 don’t know,” he replied, “1 guess 1 got just as good a job as 1 want right now. I've had offers from motorcycle distributors, and just about everyone in racing knows me, so 1 could open up a shop, or travel around. But 1 don't like traveling around. I've had enough traveling around.

“I've always had jobs that start at a certain time and get off at a certain time,” he complained mildly. “1 don’t like those kind of jobs but that’s the only kind 1 seem to get.”

Bart revealed a great deal about himself when he later recalled that the jobs he liked best were the ones he had when he was younger. In those days he did backbreaking labor, cement pouring and construction work, and when he got home at night he was exhausted. The exhaustion gave him a sense of accomplishment. Today he says he makes better money, has a softer job, but he misses that sense of accomplishment he felt, as if his body has to be worn out for him to have a satisfying day.

At AC’ he works from 3:30 in the afternoon until midnight. The reason he likes graveyard shift is because he doesn’t like getting up early in the morning.

When he comes home from work he takes a shower. (Like many athletes, Markel is always taking showers, and always looks clean and well scrubbed.) Then, quickly, he raids the refrigerator for a Coke, goes into the living room, switches on The Johnny Carson Show, kicks off his shoes, and watches television into the wee hours. Whether he gets much pleasure out of this is difficult to say. Jo Ann sometimes stays up with him, and many times they both fall asleep in front of the TV set.

On weekends, if there isn't a race somewhere, Bart frequently goes bowling with Jo Ann, who is an expert bowler. Jo Ann enjoys this, she says, because she can always beat Bart at bowling.

But games, by themselves, do not interest Bart. He plays cards, but only for money; he enjoys gambling. At the King’s Castle in Lake Tahoe he was at the blackjack table constantly, though always playing for low stakes.

In his youth, when he slept through school and worked at odd jobs, he eked out a living playing poker and shooting pool. He no longer considers himself a pool expert. Rider Dan Haaby, who is an expert at pool, won $20 from Bart a few years ago before Bart realized he was being hustled.

Another thing Bart likes to do is hunt; he has a cool hand with a pistol— usually. One year, traveling to California for some races, he and his friend Roger Reiman stopped and bought some pistols and, while speeding across the California desert, the two of them were taking pot shots out the window at tin cans and bottles along the roadside. The truck hit an unexpected bump while Markel was taking aim and Bart accidentally blasted the antenna clean off the truck, which belonged to Reiman.

Also, like a lot of professional racers, Markel is a hellishly fast driver; the courts have taken his drivers license away a couple of times because he’s gotten too many tickets.

Markel rarely goes out partying with other riders, and when he does he seems to hold himself in check much of the time. Before and after most of the National races there are a round of parties, some of which get pretty wild. At Louisville one year racer Larry Palmgren, a self-proclaimed hypnotist, asked for volunteers and Cal Rayborn, a close friend of Market's, stepped forward. Markel, who had never believed in hypnotism, watched in amazement as Palmgren put Rayborn in a trance and told him he was a dog-whereupon Rayborn got down on all fours and began barking!

That was enough for Markel. Today he is a profound believer in hypnotism, although he says he would never allow Larry Palmgren to hypnotize him. Markel has seen hypnotism work, and so he believes in it, but he regards as balderdash such things as good luck charms and lucky numbers. He also holds no faith in astrology, and doesn’t even know his own birth sign (he is, for the record, a Leo). Markel is not even

sure he believes in God: to believe in something, he insists, he must be able to see it.

Rayborn is one of the few riders who knows Markel reasonably well. Bart does not have a ‘ best” friend, although he was very close to the late Fred Nix. Another rider he was closer to than most was Chris Draayer, who lost an arm when he and Bart both went down in a bloody spill at Sedalia, Mo. in 1967. What happened to Draayer so upset Markel that he even quit racing for a time. Recently he got to know Hvel Knievel fairly well, liked him. and now worries that Knievel is going to hurt himself someday with his jumps. ”1 think 1 could do what Hvel does,” Bart has said. “The jumps, 1 mean. Probably any good motorcycle racer could. But what is amazing about Hvel is that he jumps so often —what is it. once or twice a week? You do something that dangerous. that often, it's got to catch up to you. 1 hope he doesn't hurt himself.”

One person who knows him well says that the reason Markel does not have more friends is that he lacks tact. Put another way, Bart is too honest. If he believes a friend of his has a fault, he will tell him about it so he can correct it. Honesty such as this does not go over well with a lot of people. But those who can survive Bart’s honesty find him a good friend; he will go out of his way to help them if they are in trouble.

Because Markel is such a difficult person to get to know, and is such a hard charger on any track, many people think he is a tough guy. Such a judgment is not entirely inaccurate, because Bart will not tolerate brusque treatment from anyone, regardless of who they may be.

One afternoon in the lobby of King’s C'astle, Markel saw one of his favorite actors, Lee Marvin. Bart nervously walked up to Marvin like any idolizing fan and bashfully asked the actor if he would consent to having his picture taken with him. A friend of Markel's was standing nearby with a camera.

“Later, sonny,” the actor told Markel, trying to brush him off.

Stung by this, Markel turned and began walking away. Suddenly he changed his mind, wheeled on Marvin, grabbed him in a headlock, and shouted for the friend to take the picture, which the friend did. Then Markel released the shaken Marvin from the headlock, i hanked him, and left.

Markel was not proud ol this incident; he was actually a little saddened by it. Lee Marvin will never seem so big in lus eyes again.

Actually, oil the track at least, Bart seems more inclined to be gentle than tough. He loves [iets. and usually takes lus [íet poodle, O'Brien (named alter Dick O'Brien of the Harley-Davidson racing division), to the races with him. Though Markel was a hard-punching boxer when he was a boy, he says he hasn't been in a tight in years. But one look at those piercing, incredibly blue eyes and you know he could handle himself it trouble came.

One year at the old Nelson Ledges road course in Ohio, some so-called “outlaw” riders were strutting through the pits, making nuisances of themselves by playing then self-appointed roles as toughs. Fin Kuchler, then the executive director of the American Motorcycle Association, finally lost lus temper and flung a folding chair at them that missed. The next step, apparently, was to call out the militia to get rid of them.

It wasn't necessary. Before anyone realized what was happening, the three outlaws were running out of the pits at top speed, Bart Markel running right behind them, yelling at them to turn around and fight. Powell Hassell, a southern Harley-Davidson dealer and racing authority, witnessed the whole thing.

“Bart, what were you doing with those guys?” Hassell yelled, as Markel walked back into the pits.

“Oh,” Markel replied, grinning broadly, “1 just wanted to see if they were really as tough as they were acting. They weren’t.”

Hassell concludes, “1 do believe that if Bart had caught up to those ol’ boys he would have dealt them some misery.”

No other rider at Nelson Ledges had joined Markel in the chase, but then Bart Markel has always marched to his own drummer.

Markel is wholly unpredictable.

He says he has no heroes, in or out of motorcycle racing, and maybe he doesn’t need one. He could be his own biggest hero. . . after all, he is a hero to anyone who follows racing.

He is very strong and in fine shape. He can do 30 one-handed push-ups with his nine-year-old son sitting on his back.

He doesn’t read newspapers or books, not even stories about himself.

He is a likable chap-but who really knows him?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue