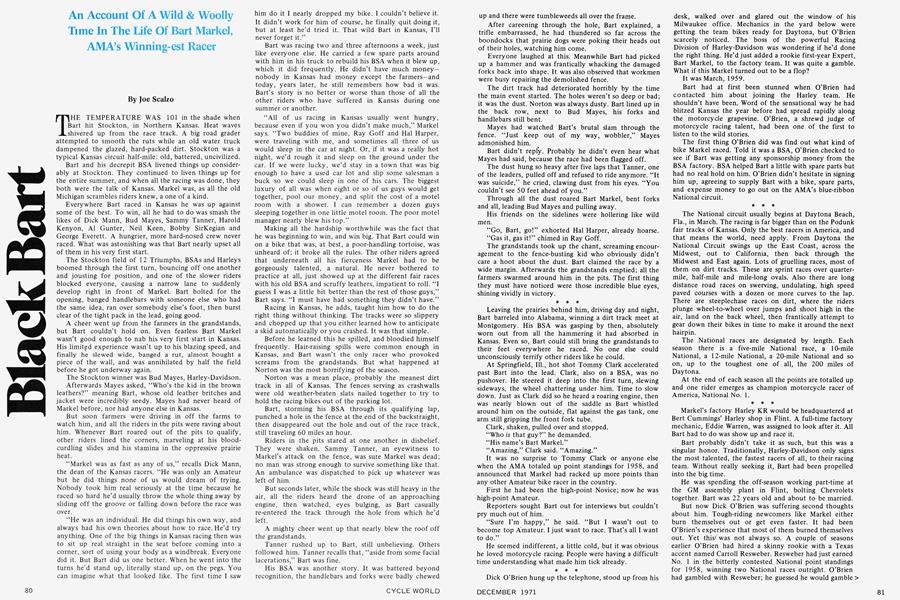

Black Bart

An Account Of A Wild & Woolly Time In The Life Of Bart Markel, AMA's Winning-est Racer

Joe Scalzo

THE TEMPERATURE WAS 101 in the shade when Bart hit Stockton, in Northern Kansas. Heat waves shivered up from the race track. A big road grader attempted to smooth the ruts while an old water truck dampened the glazed, hard-packed dirt. Stockton was a typical Kansas circuit half-mile: old, battered, uncivilized.

Bart and his decrepit BSA livened things up considerably at Stockton. They continued to liven things up for the entire summer, and when all the racing was done, they both were the talk of Kansas. Markel was, as all the old Michigan scrambles riders knew, a one of a kind.

Everywhere Bart raced in Kansas he was up against some of the best. To win, all he had to do was smash the likes of Dick Mann, Bud Mayes, Sammy Tanner, Harold Kenyon, AÍ Gunter, Neil Keen, Bobby SirKegian and George Everett. A hungrier, more hard-nosed crew never raced. What was astonishing was that Bart nearly upset all of them in his very first start.

The Stockton field of 12 Triumphs, BSAs and Harleys boomed through the first turn, bouncing off one another and jousting for position, and one of the slower riders blocked everyone, causing a narrow lane to suddenly develop right in front of Markel. Bart bolted for the opening, banged handlebars with someone else who had the same idea, ran over somebody else's foot, then burst clear of the tight pack in the lead, going good.

A cheer went up from the farmers in the grandstands, but Bart couldn't hold on. Even fearless Bart Markel wasn't good enough to nab his very first start in Kansas. His limited experience wasn't up to his blazing speed, and finally he slewed wide, banged a rut, almost bought a piece of the wall, and was annihilated by half the field before he got underway again.

The Stockton winner was Bud Mayes, Harley-Davidson.

Afterwards Mayes asked, "Who's the kid in the brown leathers?" meaning Bart, whose old leather britches and jacket were incredibly seedy. Mayes had never heard of Markel before, nor had anyone else in Kansas.

But soon farmers were driving in off the farms to watch him, and all the riders in the pits were raving about him. Whenever Bart roared out of the pits to qualify, other riders lined the corners, marveling at his bloodcurdling slides and his stamina in the oppressive prairie heat.

"Markel was as fast as any of us," recalls Dick Mann, the dean of the Kansas racers. "He was only an Amateur but he did things none of us would dream of trying. Nobody took him real seriously at the time because he raced so hard he'd usually throw the whole thing away by sliding off the groove or falling down before the race was over.

"He was an individual. He did things his own way, and always had his own theories about how to race. He'd try anything. One of the big things in Kansas racing then was to sit up real straight in the seat before coming into a corner, sort of using your body as a windbreak. Everyone did it. But Bart did us one better. When he went into the turns he'd stand up, literally stand up, on the pegs. You can imagine what that looked like. The first time I saw him do it I nearly dropped my bike. I couldn't believe it. It didn't work for him of course, he finally quit doing it, but at least he'd tried it. That wild Bart in Kansas, I'll never forget it."

Bart was racing two and three afternoons a week, just like everyone else. He carried a few spare parts around with him in his truck to rebuild his BSA when it blew up, which it did frequently. He didn't have much money— nobody in Kansas had money except the farmers—and today, years later, he still remembers how bad it was. Bart's story is no better or worse than those of all the other riders who have suffered in Kansas during one summer or another.

"All of us racing in Kansas usually went hungry, because even if you won you didn't make much," Markel says. "Two buddies of mine, Ray Goff and Hal Harper, were traveling with me, and sometimes all three of us would sleep in the car at night. Or, if it was a really hot night, we'd rough it and sleep on the ground under the car. If we were lucky, we'd stay in a town that was big enough to have a used car lot and slip some salesman a buck so we could sleep in one of his cars. The biggest luxury of all was when eight or so of us guys would get together, pool our money, and split the cost of a motel room with a shower. I can remember a dozen guys sleeping together in one little motel room. The poor motel manager nearly blew his top."

Making all the hardship worthwhile was the fact that he was beginning to win, and win big. That Bart could win on a bike that was, at best, a poor-handling tortoise, was unheard of; it broke all the rules. The other riders agreed that underneath all his fierceness Markel had to be gorgeously talented, a natural. He never bothered to practice at all, just showed up at the different fair races with his old BSA and scruffy leathers, impatient to roll. "I guess I was a little bit better than the rest of those guys," Bart says. "I must have had something they didn't have."

Racing in Kansas, he adds, taught him how to do the right thing without thinking. The tracks were so slippery and chopped up that you either learned how to anticipate a skid automatically or you crashed. It was that simple.

Before he learned this he spilled, and bloodied himself frequently. Hair-raising spills were common enough in Kansas, and Bart wasn't the only racer who provoked screams from the grandstands. But what happened at Norton was the most horrifying of the season.

Norton was a mean place, probably the meanest dirt track in all of Kansas. The fences serving as crashwalls were old weather-beaten slats nailed together to try to hold the racing bikes out of the parking lot.

Bart, storming his BSA through its qualifying lap, punched a hole in the fence at the end of the backstraight, then disappeared out the hole and out of the race track, still traveling 60 miles an hour.

Riders in the pits stared at one another in disbelief. They were shaken. Sammy Tanner, an eyewitness to Markel's attack on the fence, was sure Markel was dead; no man was strong enough to survive something like that. An ambulance was dispatched to pick up whatever was left of him.

But seconds later, while the shock was still heavy in the air, all the riders heard the drone of an approaching engine, then watched, eyes bulging, as Bart casually re-entered the track through the hole from which he'd left.

A mighty cheer went up that nearly blew the roof off the grandstands.

Tanner rushed up to Bart, still unbelieving. Others followed him. Tanner recalls that, "aside from some facial lacerations," Bart was fine.

His BSA was another story. It was battered beyond recognition, the handlebars and forks were badly chewed up and there were tumbleweeds all over the frame.

After careening through the hole, Bart explained, a trifle embarrassed, he had thundered so far across the boondocks that prairie dogs were poking their heads out of their holes, watching him come.

Everyone laughed at this. Meanwhile Bart had picked up a hammer and was frantically whacking the damaged forks back into shape. It was also observed that workmen were busy repairing the demolished fence.

The dirt track had deteriorated horribly by the time the main event started. The holes weren't so deep or bad; it was the dust. Norton was always dusty. Bart lined up in the back row, next to Bud Mayes, his forks and handlebars still bent.

Mayes had watched Bart's brutal slam through the fence. "Just keep out of my way, wobbler," Mayes admonished him.

Bart didn't reply. Probably he didn't even hear what Mayes had said, because the race had been flagged off.

The dust hung so heavy after five laps that Tanner, one of the leaders, pulled off and refused to ride anymore. "It was suicide," he cried, clawing dust from his eyes. "You couldn't see 50 feet ahead of you."

Through all the dust roared Bart Markel, bent forks and all, leading Bud Mayes and pulling away.

His friends on the sidelines were hollering like wild men.

"Go, Bart, go!" exhorted Hal Harper, already hoarse.

"Gas it, gas it!" chimed in Ray Goff.

The grandstands took up the chant, screaming encouragement to the fence-busting kid who obviously didn't care a hoot about the dust. Bart claimed the race by a wide margin. Afterwards the grandstands emptied; all the farmers swarmed around him in the pits. The first thing they must have noticed were those incredible blue eyes, shining vividly in victory.

* * *

Leaving the prairies behind him, driving day and night, Bart barreled into Alabama, winning a dirt track meet at Montgomery. His BSA was gasping by then, absolutely worn out from all the hammering it had absorbed in Kansas. Even so, Bart could still bring the grandstands to their feet everywhere he raced. No one else could unconsciously terrify other riders like he could.

At Springfield, 111., hot shot Tommy Clark accelerated past Bart into the lead. Clark, also on a BSA, was no pushover. He steered it deep into the first turn, slewing sideways, the wheel chattering under him. Time to slow down. Just as Clark did so he heard a roaring engine, then was nearly blown out of the saddle as Bart whistled around him on the outside, flat against the gas tank, one arm still gripping the front fork tube.

Clark, shaken, pulled over and stopped.

"Who is that guy?" he demanded.

"His name's Bart Markel."

"Amazing," Clark said. "Amazing."

It was no surprise to Tommy Clark or anyone else when the AMA totaled up point standings for 1958, and announced that Markel had racked up more points than any other Amateur bike racer in the country.

First he had been the high-point Novice; now he was high-point Amateur.

Reporters sought Bart out for interviews but couldn't pry much out of him.

"Sure I'm happy," he said. "But I wasn't out to become top Amateur. I just want to race. That's all I want to do."

He seemed indifferent, a little cold, but it was obvious he loved motorcycle racing. People were having a difficult time understanding what made him tick already.

* * *

Dick O'Brien hung up the telephone, stood up from his desk, walked over and glared out the window of his Milwaukee office. Mechanics in the yard below were getting the team bikes ready for Daytona, but O'Brien scarcely noticed. The boss of the powerful Racing Division of Harley-Davidson was wondering if he'd done the right thing. He'd just added a rookie first-year Expert, Bart Markel, to the factory team. It was quite a gamble. What if this Markel turned out to be a flop?

It was March, 1959.

Bart had at first been stunned when O'Brien had contacted him about joining the Harley team. He shouldn't have been. Word of the sensational way he had blitzed Kansas the year before had spread rapidly along the motorcycle grapevine. O'Brien, a shrewd judge of motorcycle racing talent, had been one of the first to listen to the wild stories.

The first thing O'Brien did was find out what kind of bike Markel raced. Told it was a BSA, O'Brien checked to see if Bart was getting any sponsorship money from the BSA factory. BSA helped Bart a little with spare parts but had no real hold on him. O'Brien didn't hesitate in signing him up, agreeing to supply Bart with a bike, spare parts, and expense money to go out on the AMA's blue-ribbon National circuit.

* * *

The National circuit usually begins at Daytona Beach, Fla., in March. The racing is far bigger than on the Podunk fair tracks of Kansas. Only the best racers in America, and that means the world, need apply. From Daytona the National Circuit swings up the East Coast, across the Midwest, out to California, then back through the Midwest and East again. Lots of gruelling races, most of them on dirt tracks. These are sprint races over quartermile, half-mile and mile-long ovals. Also there are long distance road races on swerving, undulating, high speed paved courses with a dozen or more curves to the lap. There are steeplechase races on dirt, where the riders plunge wheel-to-wheel over jumps and shoot high in the air, land on the back wheel, then frantically attempt to gear down their bikes in time to make it around the next hairpin.

The National races are designated by length. Each season there is a five-mile National race, a 10-mile National, a 12-mile National, a 20-mile National and so on, up to the toughest one of all, the 200 miles of Daytona.

At the end of each season all the points are totalled up and one rider emerges as champion motorcycle racer of America, National No. 1.

* * *

Markel's factory Harley KR would be headquartered at Bert Cummings' Harley shop in Flint. A full-time factory mechanic, Eddie Warren, was assigned to look after it. All Bart had to do was show up and race it.

Bart probably didn't take it as such, but this was a singular honor. Traditionally, Harley-Davidson only signs the most talented, the fastest racers of all, to their racing team. Without really seeking it, Bart had been propelled into the big time.

He was spending the off-season working part-time at the GM assembly plant in Flint, bolting Chevrolets together. Bart was 22 years old and about to be married.

But now Dick O'Brien was suffering second thoughts about him. Tough-riding newcomers like Markel either burn themselves out or get even faster. It had been O'Brien's experience that most of them burned themselves out. Yet this^was not always so. A couple of seasons earlier O'Brien had hired a skinny rookie with a Texas accent named Carroll Resweber. Resweber had just earned No. 1 in the bitterly contested National point standings for 1958, winning two National races outright. O'Brien had gambled with Resweber; he guessed he would gamble with Bart Markel, and await the consequences.

Other than Resweber and Markel, O'Brien sent Joe Leonard and Brad Andres, both former holders of No. 1, to the Daytona Beach 200-miler in March. Daytona would be Bart's first start as an Expert class rider.

But Bart had other, more pleasant, business in Daytona Beach. He and Jo Ann were married in his grandmother's home in nearby Shockley Hills the week before the 200. Their honeymoon was postponed for a week so that Bart could make his debut as a factory rider.

Jo Ann's confidence in Bart was boundless. She actually believed Bart would win Daytona, even though he'd never seen the place before. But the lukewarm reception she received from the other wives chilled her. "I knew who they were, I'd heard about their husbands, but they didn't know who I was, and they acted like they'd never heard of Bart," Jo Ann recalls. "I felt uncomfortable around them. They seemed so smug."

Actually there was dissention on the Harley team. Resweber, Leonard and Andres, the senior riders, were a bit annoyed that Dick O'Brien had added a green first-year Expert like Markel to their haughty group; they, after all, were the cream.

Bart didn't seem to notice or care. He was busy falling in love with his very first Harley racer. Sitting in the saddle, he levered the brakes and the clutch, kicked the bike in and out of gear with his foot, worked the throttle, grinning happily as he made the big engine roar.

Later the annoyance deepened, and so did the shock. Bart exploded past Resweber, Leonard and Andres on the mile-long backstraight, rudely demonstrating to the three that his was the fastest, most powerful Harley on the team!

Bart himself was astonished. But he had had little to do with the bike's incredible speed. The individual responsible was his new tuner, young Eddie Warren.

Warren was a part-time bike racer himself. He'd had a promising career until he slammed into a cement truck on the street one day and ruined his collarbone. A softspoken perfectionist with a crew cut, Warren was a much better mechanic than he was a racer. He'd toiled and fussed over Markel's engine all winter, and had pulled gobs of raw power out of it.

During practice rounds on the two-mile-long Daytona oval with its front straightaway right along the white-sand beach front, Bart's bike was louder than everything else. The sound of it could be heard all the way around the track. Dick O'Brien paced up and down the beach, watching Bart anxiously. He was startled that Bart could drive so deep into the turn at the end and not fall.

O'Brien was pleased, and with good reason. There was something just right about Bart Markel racing a HarleyDavidson. The factory KR Harleys were big bastards, tough as tanks and, at over 300 lb. apiece, nearly as heavy. Their old flathead engines were practically museum pieces. But a KR could devour Daytona's damp, sandy front straightaway at 137 mph, and eat up the backstraight at better than 140. This was nearly 10 mph faster than any other bike from any other team. Moreover, the heavy KRs could be rammed through deep potholes that would buckle the wheels of most other bikes. The factory KR Harley was a man's motorcycle, and it took a man to ride one really fast and get all the power onto the ground.

What better man than Bart Markel?

Daytona, 1959, was the beginning of Bart's career-long stay with Harley. Rider and bike complemented one another exquisitely.

After getting to know the potential of his new mount, Bart estimated that it was at least 30 mph faster than his old BSA. "I'd gotten so used to winning with that underpowered BSA that I just can't believe all this speed," he told Warren.

"Just keep it on the ground," Eddie reminded him.

Markel was so hungry to be the fastest qualifier that he bolted out of the pits riding the back wheel, an elaborate wheelie that lasted for 100 ft. Shifting gears, Bart let the front wheel smash down hard, tucked in, then began eating up the course, spewing sand and noise.

His speed was a slow 112 mph.

"What happened Bart, what went wrong?" demanded Eddie Warren, frantic.

"I don't know," Bart replied, mad. "She just wouldn't pull no rpms up the front straight."

Warren looked the bike over, found nothing wrong. It wasn't until he pushed it toward the garage that he felt the front brake dragging. Bart had damaged it during his blazing pit getaway.

No problem then. On Sunday Bart would be starting toward the rear in a field of 100 riders, but he had the guts and horsepower to move up right away.

The problem was that Daytona demanded a special riding technique; you had to keep control, and somehow stay on two wheels in the sandy corners. It took concentration and some finesse. Finesse at this time was something Bart Markel did not possess at all.

But at first, just like in Kansas, it looked like the rookie Markel might blow off the field. He came boring out of the pack in the blowing sand, his engine still louder than all the rest.

It was awesome, unbelievable. In one two-mile lap Markel had simply overwhelmed every rider there except his new teammate, Joe Leonard. Now Leonard was just ahead of him in the track, and Bart ate him alive on the rutted run to the first turn.

Bart was leading.

Leonard, savvy, tough, immediately grabbed the lead back from Markel, powering through the deep sand, bumping Bart out of the way.

Markel didn't quit. Down the long backstraight, Bart flattened himself against the gas tank, aimed his bike at Leonard's back wheel and rode in his slipstream, both men exceeding 140 mph on the narrow road, only inches apart.

Two hundred feet from the corner at end, Markel rolled back the throttle and slowed. Brad Andres and Everett Brashear rocketed past him, closing in on Leonard.

A wild melee broke out for the lead.

Bart was upset. His was the fastest Harley at Daytona, yet he was only 4th. Forcing the pace, he nailed the throttle wide open, and that frighteningly powerful engine catapulted him past Leonard, Andres and Brashear into the lead once more.

Determined not to be outbraked and lose the lead again, Bart took it sickeningly deep into the corner. Too deep. Before he could yank on the brakes he was skidding wildly in the deep sand. Then he went down in a heap.

Leonard, Brashear and Andres were past him in an instant. Bart jerked his stalled bike out the sand and watched them go. His goggles had been crushed in the spill so he flung them aside. He'd continue without goggles.

"I'm gonna catch you guys," he heard himself snarl, getting the bike going again.

He wasn't sure how many bikes had gone by while he was lying in the road. Too many. So he gave the huge engine its head one last time and tore along the beach front. He moved violently and rapidly forward. The pistons were going up and down so hard they sounded like they'd explode through the cylinder heads. All Bart could think about was running down those three devils ahead of him. He was that intent on winning.

By now he was overtaking slow traffic. He thought he recognized the helmet of Andres far ahead and believed he was catching him.

But he could barely see without goggles, his eyes were filled with blowing sand and burned like hell. Bart was having more and more close calls ... a tremendous crash at the great speed he was traveling was only a matter of time.

Finally, at 140 mph, he ran straight into the back of a squat, heavy BMW going 20 miles an hour slower.

The soft sand saved Bart's life. Today he recalls seeing the BMW at the last instant, trying unsuccessfully to swerve out of the way, then the thudding, ripping noise of contact. After this the dreamy sensation of pinwheeling through the air, his precious Harley suddenly forgotten. And then splatting the wet sand with terrible impact, knocking himself out, and waking up frightened because he could neither breathe nor see—sand had momentarily clogged his throat and eyes.

Jo Ann Markel heard of Bart's crash over the public address system. But the announcer's account was garbled; noise from the race made it hard to hear. For lap after lap Jo Ann had watched her husband rocket down the front straight so fast she could barely be sure it was him. Then, terrifyingly, he didn't come round anymore.

"I started running down the track looking for Bart," Jo Ann remembers. "I had to find him! But when I got to where the accident had happened they'd taken him away, and all I could see was his bike up on top of a car in the spectator area where it had landed. Somebody told> me Bart was at the infield hospital. Thank God, I found him there. He smiled at me but there was blood and sand all over his face. He was alright. Then he said, ‘Boy, honey, I really look great, don't I?' And he laughed that same silly laugh he had on our first date. I started to cry with relief . . ."

Joe Leonard, without Markel hounding him, outlasted Andres and Brashear to easily win the 200. But Leonard was on the way out with the Harley team; he was in the process of launching a race car driving career instead. Bart Markel was Leonard's obvious replacement. Dick O'Brien had been thrilled by Bart's guts and fire. With little experience under his belt, Bart had led his very first Daytona. And even without goggles he'd returned unbelievably quick lap times. Certainly he had crashed and torn up an expensive team bike. The bike could be replaced, but where could O'Brien find another Bart Markel? No, the pragmatic boss of the Harley team wasn't upset by Bart's crash at all.

Nor, for that matter, was Bart. He slapped a bandage on his face, checked out of the hospital that night, and told Jo Ann to drive him back to Flint; he wasn't up to driving himself.

Jo Ann didn't own a driver's license, had only driven a car a couple of times in her life before, but she was up to the task. Driving straight through without sleep, she had Bart back to Flint in 30 hours. So much for the honeymoon.

The following morning Bart returned to work at Chevrolet. Budding star motorcycle racer or not, he still had to work for a living.

* * *

A sidelight to Markel's brutal Daytona crash occurred nearly five years later, in 1964, on a Pennsylvania dirt track. Bart and a young Michigan rider named John Zwerican had driven in for the meet, and during a hard-fought heat race the aggressive Zwerican inadvertently ran over a local rider's foot.

Afterwards there was a lot of yelling and shoving, and the angry local rider and some of his friends planned to gang up on Zwerican and beat him to a pulp.

Bart rushed over and broke up the fight before it began.

One of the disgruntled locals sneered at Bart, "What's the matter, Markel? Have you been giving Zwerican lessons in how to ride rough?"

Bart bristled. "How can you talk to me like that?" he demanded. "I've never even seen you before."

"The hell you haven't," the other rider retorted. "I'm the guy you crashed into at Daytona in 1959 on the BMW."

Bart gaped at him. He had almost forgotten about Daytona. Finally he replied, contrite, "I guess I didn't recognize you. Well, I never got a chance to apologize to you four years ago, so I'll do it now. I'm sorry I ran into you."

Reluctantly, the other rider accepted the apology. "You've come a long way since then," he finally admitted to Bart. "You're the best bike racer in the country today."

* * *

Licking his wounds from Daytona, Bart spent the rest of 1959 fruitlessly trying to overtake his great Harley teammate Carroll Resweber. Dick O'Brien gave him a new KR to replace the one he'd wrecked at Daytona, but it didn't help much. This was the beginning of the longest, fiercest, most brilliant rivalry in recent motorcycle racing history.

Bart couldn't touch Resweber at first. The wily little Resweber was simply too much for him on dirt tracks. Resweber was too much for everyone. He had been champion of America, No. 1, in 1958, and he repeated it in 1959.

Trying to beat Resweber, Bart took ludicrous gambles on most dirt tracks. Eddie Warren wanted him to be more careful. "Darn it, Markel," Warren warned, "why don't you slow down and settle for 2nd?"

Bart overruled him. "Ed, as soon as a guy starts settling for 2nd he's going to start settling for 3rd. And then 4th. Pretty soon you're out of business. I'm here to race Resweber, and I'm going to race to win."

Warren was getting 20 percent of Bart's winnings. He respected Bart's opinion. "Okay, if that's the way it is."

That's the way it was. With Markel, it's the way it will always be.

Warren believed that the reason Bart had to charge so hard was because his Harley wasn't powerful enough. Warren continually apologized to Bart for not building a machine that was fast enough for him.

Bart replied that he had plenty of horsepower, and that the reason he couldn't beat Resweber during 1959 was because Resweber was better than he was. So Bart kept pushing hard, and sometimes he crashed hard, but he never seemed to hurt himself or his spirit.

"Eddie was always telling me the bike wasn't fast enough. I always told him that it was plenty fast enough, and that I just had to crack 'er on a little more."

In 1959, his first year as an Expert on the National circuit, Markel placed 4th at St. Paul, Mich., 5th at Columbus, Ohio, and an incredible 2nd behind Resweber at Springfield, 111., in the big 50-mile National. Bart was rated the seventh best Expert in America, an amazing showing for a rookie, although he himself wasn't overly impressed by it.

His motorcycle racing career was accelerating at breakneck speed.

By now Dick O'Brien was sure he'd made the right choice and that Bart Markel was one rider in a million. O'Brien's big gamble hadn't been a gamble at all. He stood by Bart all season offering encouragement, helping him in any way he could.

O'Brien also stood by Markel the following season. This took guts. Boilࢮing controversy suddenly erupted in 1960 over Bart's aggressive riding, and finally the American Motorcycle Association got sick of him and banished him from the tracks for awhile.

By then the mob called him "Black Bart." [Ô]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

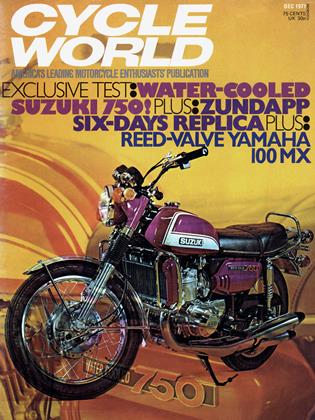

DepartmentsRound Up

DECEMBER 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

DECEMBER 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

DECEMBER 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesViewpoint: the Road Bike In Tomorrow's World

DECEMBER 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

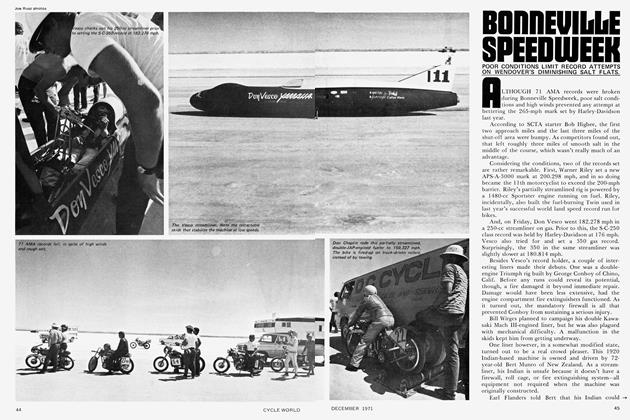

CompetitionBonneville Speedweek

DECEMBER 1971