THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

IT is not my intention to become lazy and turn this column into another reader letter service; however, a recent correspondent made some very good points that deserve more than standard treatment. Mr. Mike Stephenson wrote his letter after reading my special report in the September issue regarding a University of California, Los Angeles, motorcycle crash study. Following is the letter in its entirety:

Because of the aura of authenticity which accompanies studies of this type, the results and conclusions frequently influence legislative thinking more than is warranted. You undoubtedly have formed some opinions on the validity of this particular experimental effort. I would like to take this opportunity to pass along a few of my own, based on personal observation and experience. I'll confine my comments to the experimental work and conclusions, the objectivity and competence of the authors being something with which I'm slightly familiar, but not relative specifically to motorcycles.

My interest in motorcycles is purely avocational; however I do occasionally give expert testimony in civil suits involving motorcycle accidents. Accordingly, I've looked at about 25 specific accidents in the last year, perhaps 10 of them being of the "auto center punch'' variety studied in the article. Most of the rest involved alleged mechanical failures. So much for background . . .

First of all, I should say that lam not of the Ralph Nader school, and don't believe that any mechanical device which cannot be operated successfully by a five-year-old child should be legislated out of existence. In my experience, the majority of auto/motorcy cle accidents, even those caused by the auto primarily, involve a mental or physical error on the part of the motorcyclist. Not necessarily a legal error, nor perhaps even an error by automobile standards. But the rider who operates his bike like the average driver operates his car is strictly a temporary member of our fraternity anyway. Accordingly, I find the article lacking in proper emphasis. School affiliated driver's education courses should definitely include a motorcy cle option. Clubs and dealers should similarly instill in potential riders not only a physically manipulative ability, but also a thorough knowledge and appreciation of the highway pecking order and the place of the motorcycle therein. Emphasis on mechanical modifications, where it tends to obscure this anti-accident concept, is not beneficial. So much for general editorializing. Back to the article.

The nature of the conclusions drawn by the authors forces me to quibble somewhat with their experimental technique. The use of anthropometric dummies to simulate humans necessarily, and often correctly, assumes minimal efforts at body control. I believe, in simulating motorcyclists in collision, that this assumption is seriously erroneous. My experience has been that a rider in vertical collision (no time for lay down, etc.) grips the handlebars with inordinate force prior to impact. He thus is not thrown straight ahead, but is rather pivoted up and over the bars at impact as the rear wheel bounces into the air due to the couple set up by the front wheel impact force and the higher bike/ rider c.g. Normally the rider is thrown well over the car, and sometimes as high as 7 or 8 ft. in the air, or higher. He almost never pivots forward into the hood or trunk, as evidenced by, normally, a total lack of damage to these surfaces. Thus, the leg restraints, as proposed, would be of questionable value unless they provided at least as much vertical restraint as horizontal restraint. Similarly, motorcyclists just are not pitched into the headlight /steering head assembly. Restraints are not only ugly and cumbersome, but are based on erroneous assumption of rider kinematics. The air bags mentioned are a better, more practical idea, if well designed. However use of a full fairing is an even better, more functional idea. Having rear-ended a pickup at about 10 mph while skirtwatching, shearing off an Avonaire windshield with my chest in the process, I can attest to the value of fairings in the specific type of lowspeed collision studied. The windshield slowed me down enough to stay on the bike, and I didn't even get a bruise. And of course the added confinement, with accompanying degradation of evasive ability, should not be overlooked for any kind of passive restraint.

Regarding building some sort of shock mitigating feature into the front of the engine, this strikes me as a poorly thought out idea. First of all, if the car is not stationary at impact (the more normal situation) the wheel is not driven back into the engine as stated by the authors, but is pivoted to the right or left (depending on direction of car travel). The rear portion of the tire/wheel is then driven back into an exhaust pipe, a side case, or may miss the engine altogether. Such things, as, for instance, front cylinder fins made from aluminum honeycomb, would be totally useless in most circumstances. Secondly, adding any mitigating material to the space available would not result in more energy absorption prior to total crush-up, but would increase the "g" level during crush-up, facilitating rear wheel levitation and rider ejection. I question whether the net effectiveness is obvious.

While drawing conclusions is within the scope of this type of study, I doubt that drawing a conclusion based on one chopper/Cougar accident is valid scientific method. I have examined one case involving a stock Honda 350 which struck an auto near the right rear tire with sufficient force to spin the auto (a full-sized Chevrolet) through 140 deg. The rider flew 50 ft. down the road and sustained only superficial injuries. I would be reluctant to conclude from this that all bikes should be equipped with Honda 350 front forks. Conclusions that extended forks are even beneficial, much less innocuous from a handling standpoint, seem both unsubstantiated and irresponsible. At the risk of sounding smug, I'll point out that turning auto drivers loose to run motorcycle experiments seems a low probability method of arriving at meaningful conclusions, no matter how well designed the experiments.

If we throw out most of the conclusions based on the author's perception of rider kinematics, which I contend don't apply at low-tomoderate speeds, and also throw out those conclusions based on extrapolation of data from a very specific kind of accident with a very specific bike orientation, I pretty much agree with what they have to say. Helmets are good; bikes are easier to see with the light on; sliding under trucks is unhealthy ; motorcycles decelerate when they hit cars; occupants of the cars rarely get hurt; etc. Their [UCLA's] general tendency to make statements without sufficient qualifiers, however, is disturbing. Their emphasis on what must be done obscures the more productive nonmechanical things which should be done. Clearly the easiest way to avoid accidental injuries is to avoid accidents.

Although Mr. Stephenson's letter did reinforce my position on several points in the study, my primary purpose in reprinting it was for the additional information he was able, in his capacity as a registered professional engineer giving expert testimony, to supply us with. One interesting point in particular is the tendency for the front forks to be whipped to one side or the other if the car is moving at the time of impact, which usually is the case. In that instance, longer forks would not provide greater crunch space for energy management. On the contrary, they may even offer greater leverage on the extended frontal structure, causing less energy absorption than a standard front end, thus placing higher g forces on the rider.

(Continued on page 89)

Continued from page 32

At least one engineer in the Department of Transportation has absorbed the UCLA study and is serious about requiring longer than conventional forks; his position will be the same six months from now. He really believes it is a valid safety feature. But, like the authors of the UCLA study, the DOT engineer is not a motorcyclist.

Another point of Mr. Stephenson's letter which backs up my original objections to the UCLA study is the use of dummies (although I still don't want to volunteer in the experiment). At this time the DOT is very concerned about the development of a new, more sophisticated anthropometric dummy which, when fully instrumented, will better simulate the actions of the human body in accidents of high g force situations. Considerable research effort will be applied to the project, and I'm sure that new-generation dummies will be invaluable in the evaluation of restraint systems for automobiles. But they will be no better than present state-of-the-art dummies for motorcycle collisions with fixed objects or other vehicles. Because, as confirmed by Mr. Stephenson, there is a human reaction on the part of the rider, at the handlebars and during the separation period at the time of actual contact, which cannot be simulated mechanically.

We both seem to have the same conclusions about the merits of training the rider and trying to prevent the crash. There is a phenomenon which drivers, especially those less skilled, tired or drunk, exhibit of being attracted toward a moving object. A California Highway Patrol spokesman told me that the department lost 18 men in 1969 on freeways and high speed roads, when the officers had pulled cars over to the side of the road, and the flashing amber lights were operating. It seems that even the small attraction offered by the flashing lights will cause a person in a distressed state to drive towards the moving object.

This phenomenon is present to a certain degree when a person is not completely competent in the operation of the vehicle under his command. Young pilots will, for instance, foul up a landing because of a movement on the ground while they are on final approach, or will sometimes fly directly at the flashing lights of another plane. I remember very well running into a dog when I first started to ride motorcycles. I was probably traveling 20 mph as the strange reason the dog was a magnet, and I steered, somehow automatically, at it. Yet years later, at more than 100 mph at the Isle of Man road race in practice, I missed a sheep wandering around the road. In racing, expert riders, who have gained an intimate feel and confidence in their machinery, are able to slither through several bikes in incredible situations, while a novice rider may centerpunch the first target he sees. This holds true for Daytona or Le Mans or bikes or cars.

If you accept this theory, whether it is regarding the use of a car, airplane, motorcycle or skiing, everything points to the need for better rider training. As Mr. Stephenson points out, safe driving habits for car drivers do not apply to the motorcyclist. Survivability on a motorcycle is a whole different ball game, one that needs to be practiced.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

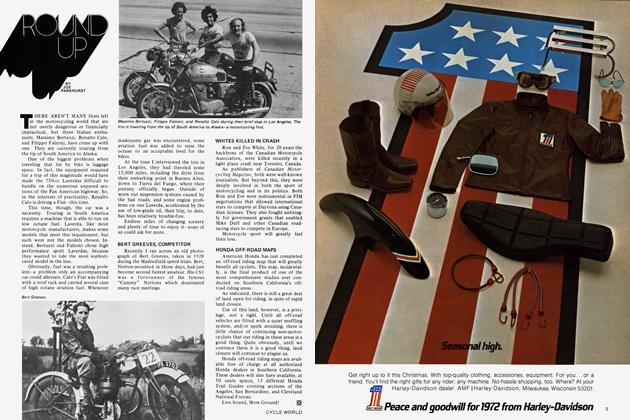

DepartmentsRound Up

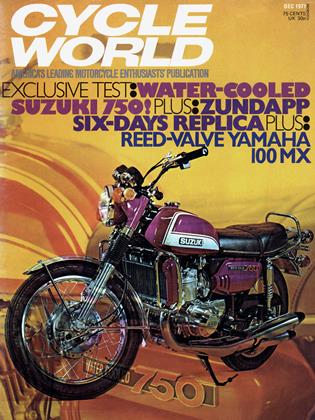

DECEMBER 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

DECEMBER 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Features

FeaturesViewpoint: the Road Bike In Tomorrow's World

DECEMBER 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

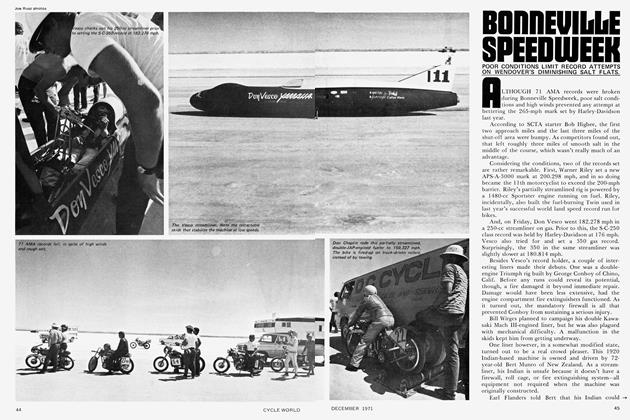

CompetitionBonneville Speedweek

DECEMBER 1971 -

Technical

TechnicalThe Pneumatic Tire

DECEMBER 1971 By William Hampton