Whatever happened to Eddie Mulder?

JOE SCALZO

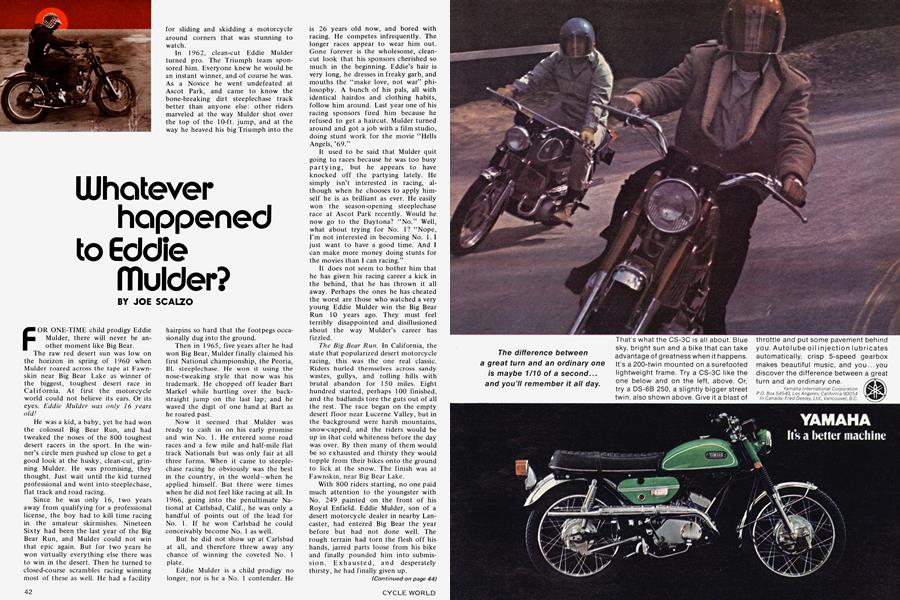

FOR ONE-TIME child prodigy Eddie Mulder, there will never be another moment like Big Bear.

The raw red desert sun was low on the horizon in spring of 1960 when Mulder roared across the tape at Fawn-skin near Big Bear Lake as winner of the biggest, toughest desert race in California. At first the motorcycle world could not believe its ears. Or its eyes. Eddie Mulder was only 16 years old!

He was a kid, a baby, yet he had won the colossal Big Bear Run, and had tweaked the noses of the 800 toughest desert racers in the sport. In the winner’s circle men pushed up close to get a good look at the husky, clean-cut, grinning Mulder. He was promising, they thought. Just wait until the kid turned professional and went into steeplechase, flat track and road racing.

Since he was only 16, two years away from qualifying for a professional license, the boy had to kill time racing in the amateur skirmishes. Nineteen Sixty had been the last year of the Big Bear Run, and Mulder could not win that epic again. But for two years he won virtually everything else there was to win in the desert. Then he turned to closed-course scrambles racing winning most of these as well. He had a facility for sliding and skidding a motorcycle around corners that was stunning to watch.

In 1962, clean-cut Eddie Mulder turned pro. The Triumph team sponsored him. Everyone knew he would be an instant winner, and of course he was. As a Novice he went undefeated at Ascot Park, and came to know the bone-breaking dirt steeplechase track better than anyone else: other riders marveled at the way Mulder shot over the top of the 10-ft. jump, and at the way he heaved his big Triumph into the

hairpins so hard that the footpegs occasionally dug into the ground.

Then in 1965, five years after he had won Big Bear, Mulder finally claimed his first National championship, the Peoria, 111. steeplechase. He won it using the nose-tweaking style that now was his trademark. He chopped off leader Bart Markel while hurtling over the backstraight jump on the last lap; and he waved the digit of one hand at Bart as he roared past.

Now it seemed that Mulder was ready to cash in on his early promise and win No. 1. He entered some road races and a few mile and half-mile flat track Nationals but was only fair at all three forms. When it came to steeplechase racing he obviously was the best in the country, in the world—when he applied himself. But there were times when he did not feel like racing at all. In 1966, going into the penultimate National at Carlsbad, Calif., he was only a handful of points out of the lead for No. 1. If he won Carlsbad he could conceivably become No. 1 as well.

But he did not show up at Carlsbad at all, and therefore threw away any chance of winning the coveted No. 1 plate.

Eddie Mulder is a child prodigy no longer, nor is he a No. 1 contender. He is 26 years old now, and bored with racing. He competes infrequently. The longer races appear to wear him out. Gone forever is the wholesome, cleancut look that his sponsors cherished so much in the beginning. Eddie’s hair is very long, he dresses in freaky garb, and mouths the “make love, not war” philosophy. A bunch of his pals, all with identical hairdos and clothing habits, follow him around. Last year one of his racing sponsors fired him because he refused to get a haircut. Mulder turned around and got a job with a film studio, doing stunt work for the movie “Hells Angels, ’69.”

It used to be said that Mulder quit going to races because he was too busy partying, but he appears to have knocked off the partying lately. He simply isn’t interested in racing, although when he chooses to apply himself he is as brilliant as ever. He easily won the season-opening steeplechase race at Ascot Park recently. Would he now go to the Daytona? “No.” Well, what about trying for No. 1? “Nope, I’m not interested in becoming No. 1. I just want to have a good time. And I can make more money doing stunts for the movies than I can racing.”

It does not seem to bother him that he has given his racing career a kick in the behind, that he has thrown it all away. Perhaps the ones he has cheated the worst are those who watched a very young Eddie Mulder win the Big Bear Run 10 years ago. They must feel terribly disappointed and disillusioned about the way Mulder’s career has fizzled.

The Big Bear Run. In California, the state that popularized desert motorcycle racing, this was the one real classic. Riders hurled themselves across sandy wastes, gullys, and rolling hills with brutal abandon for 150 miles. Eight hundred started, perhaps 100 finished, and the badlands tore the guts out of all the rest. The race began on the empty desert floor near Lucerne Valley, but in the background were harsh mountains, snow-capped, and the riders would be up in that cold whiteness before the day was over. By then many of them would be so exhausted and thirsty they would topple from their bikes onto the ground to lick at the snow. The finish was at Fawnskin, near Big Bear Lake.

With 800 riders starting, no one paid much attention to the youngster with No. 249 painted on the front of his Royal Enfield. Eddie Mulder, son of a desert motorcycle dealer in nearby Lancaster, had entered Big Bear the year before but had not done well. The rough terrain had torn the flesh off his hands, jarred parts loose from his bike and finally pounded him into submission. Exhausted, and desperately thirsty, he had finally given up.

(Continued on page 44)

Continued from page 42

The race started in the early morning. The field of 800 stretched in one line for more than a mile across the desert. The riders stared straight ahead at the undulating desolation that faced them.

A smoke bomb was triggered, and the 800 kicked over their engines and roared away.

All of them but Eddie. Fighting a last-minute attack of nervousness, he was in one of the makeshift outhouses when the race started. Ele heard the sudden roar, immediately realized what had happened, and dashed out the door. His father, AÍ Mulder, calmly stood there holding his motorcycle. Eddie leaped aboard. He kicked over the engine, jammed the throttle wide open, the front wheel shot high in the air and he was off, a furious cloud of dust billowing up behind him.

Mulder was young enough to have no fear, and precocious enough to believe he could overtake all 799 riders ahead of him. Of that 799, perhaps 500 were weekend warriors who had no thoughts of winning; they merely wanted to brag to their friends afterwards, “I rode in the Big Bear Run.” Yet the remaining 199 were the toughest, most savvy desert racers in California, and these were the ones Mulder had to overwhelm.

Mulder must have ridden like the devil himself. After only 50 miles he had passed 775 riders and was 15th, grazing yucca plants and boulders and hardly ever rolling back the throttle.

After 100 miles he was 8th. His frantic pace was beginning to tell, though. As he charged up Rattlesnake Canyon at 80 mph he scraped off the bike’s right footpeg against the side of a huge boulder.

The brush was so high in places he could barely see, and as the route swung through sand washes and up the sides of mountains, Mulder was tiring. He also was gaining ground at a colossal rate. As he skidded around a corner he found Don Surplice, one of the favorites, stalled. A plug had fouled in his engine.

“Eddie, do you have a plug wrench?” Surplice asked miserably.

“Nope, I sure don’t,” Mulder answered, preparing to leave. Surplice told him, “You are in 2nd place. Babe Jay is only about a minute or two ahead of you—”

The rest of Surplice’s message was lost in the roar of Mulder’s exhaust.

It took him less than 15 minutes to catch, pass, and pull away from Babe Jay. Now he was leading, but instead of easing up he rode faster and faster and nearly threw away the whole race while charging up the face of a mountain along a narrow zig-zagging dirt road.

Mulder was skidding the hairpin corners, charging, and finally he careened off the side. He and the bike crashed through sagebrush and bounced off sharp rocks for hundreds of feet before tumbling onto the road below.

The fall had pulled loose the exhaust pipes from the cylinder head, ripped off one of the rear shock absorbers, and tore a gash in Mulder’s forehead. Fortunately the finish was only a few miles ahead, for it would have been inconceivable to expect the bike (or Mulder) to go much further after this. As it was, he was able to baby the battered RoyalEnfield the rest of the distance and still win.

Perhaps the one person not flabbergasted by Mulder’s stunning victory was his father. “Eddie just always loved bikes,” AÍ Mulder explained at the time. “When he was eight years old he’d go ride in the sand washes. He always had a fine sense of balance. He always was just plain good.” Eddie himself told how he had ridden his first motorcycle: “I jumped on it at dad’s shop. I turned the throttle wide open, then held on. I really dug it.”

As a racer, Mulder possessed such great natural talent he probably would have reached stardom even if he had not won Big Bear. But winning Big Bear made him a superstar overnight. Suddenly he felt very important. When he was stopped for speeding on a highway near his home he supposedly attempted to quash the ticket by smugly telling the cop, “My name’s Eddie Mulder. I won the Big Bear Run when I was 16.” Eddie was mortified when the cop wrote him up regardless. By winning Big Bear, he had tweaked the noses of all the older, established stars. Maybe because he had won so easily he now believed he could win anywhere, and did not have to try very hard.

Certainly the wins came easy to him at Ascot Park during the early Sixties, his first years as a professional. Or, if they did not come easy, Eddie managed to make them look easy. The seven-turn Ascot steeplechase track is only 5/8ths of a mile long, shaped like a half-moon, with a single, lethal, high-speed jump in the middle. In his first race, Mulder shot so high into the air going over the jump and qualified so fast he had to face experts like Dick Dorresteyn, Sid Payne, and Jack O’Brien in the trophy dash. He wasn’t awed by them in the least: “If they can ride fast, I can too.” He won the three-lap race with ease. He celebrated this feat by executing a flashy wheelstand directly in front of the grandstand.

Afterwards, as the fans trooped out of the stands and rushed to his side, it must have seemed like Big Bear all over again to Mulder. Once again he had tweaked the noses of the accomplished stars. And he still was only a kid.

He was rated the No. 1 Novice racer in America. The following year, racing as an Amateur, or second-year rider, he won 57 races in all, including seven trophy dashes in a row. If the motorcycle did not break, he would win; it was as simple as that. He still liked to beat the Expert riders most of all. He could beat them so easily that the racing may have been boring to him already.

Triumph sent him to Peoria in 1965 as an Expert. He won his first National there by passing Markel and spraying him with dirt. Since Markel was the No.

1 rider in the country at the time, Mulder says that beating him was “quite a thrill.”

Mulder nearly won No. 1 for Triumph in 1966, the year he accomplished the impossible by winning all three steeplechase Nationals at Castle Rock, Wash., Ascot, and Peoria. Going into the Carlsbad road race that winter, he trailed Bart Markel and Gary Nixon by a mere 31 points. But to the chagrin of Triumph, who had built up a really fast bike for him, Mulder did not go to Carlsbad. Instead he stayed home. “I just wasn’t interested,” he says today, shrugging his shoulders.

It was a bad time for him all the way around. He was married and had two children, but he and his wife were in the middle of a divorce.

With his decision not to go to Carlsbad, Mulder renounced his serious racing career. This did not surprise the other riders. Few of them like him much anyway. Partly this was because he beat them so often, so easily. They always considered him a show-off, a smart aleck. After he had beaten them, he loved to rile them, “Because it makes them crazy.”

Mulder was and is loud, boistrous, a prankster, and even his best friends call him “Squirrel.” He may not be interested in winning No. 1 anymore, but this does not keep him from dreaming up more and more mind-blowing pranks.

(Continued on page 46)

Continued from page 44

At an Ascot Park race not so long ago, the Triumph rider Skip Van Leeuwen—perhaps Mulder’s closest friend among the Ascot crowd-broke down early. For a joke, Van Leeuwen dashed onto the track and began hitch-hiking. Mulder, leading the race, screeched to a stop. Grinning broadly, he motioned Van Leeuwen to climb on behind him.

It became immediately apparent to everyone at the track that Eddie planned to scare hell out of his passenger.

“Hell, yes, I was out to scare Skip,” says Mulder today, a wild look creeping into his eyes as he recalled the incident. “I just wound that 40-in. Triumph out in second gear, then third, and finally caught fourth. By now we were really getting it on. I was starting to get a little scared. But I just kept gassing it, because I wanted to hear Skip scream. And finally, just as we hit the finish line and I got the checkered flag he screamed, ‘Slow this—down!’ Oh, he really screamed bitchin’.”

For this “prank” Mulder and Van Leeuwen both were fined $50 by the American Motorcycle Association.

During his up-and-down career, Mulder has had numerous brushes with the AMA. It is a good bet that at any AMA race he attends he will become embroiled in at least one good argument with the starter. Getting the jump at the start may be Mulder’s greatest single talent as a motorcycle racer. He moves off the line so quickly that it is impossible to believe anyone could possess such reflexes. At Lincoln, Neb. two years ago, the entire front row, Mulder included, jumped the gun and was called back. The starter impatiently motioned Mulder to the back line; no one else was so penalized. This made Eddie so mad that he dropped the clutch and rode over the starter’s foot. Afterwards he drove straight into the pits.

He had come 2000 miles to race and did not ride a single lap. He was not disciplined for roughing up the starter.

Last year at San Jose he socked a starter in the jaw. And at Whiteman Stadium near Los Angeles he felled the race promoter with a single punch after a dispute over prize money.

Lately, tweaking the nose of the AMA that much more, Eddie has grown a full beard (since shaved off) and let his hair get so long it flows out the back of his helmet. He painted the peace sign on the gas tank of his bike and on his helmet. He looks like a hippie but says he is not. “People think I’m a freak, right?” he asks rhetorically. “Well, sure 1 wear weird clothes and long hair. But those other people are behind the times, not me.” The AMA officials, interested in the “image” of motorcycle racing, do not like Mulder’s bizarre appearance and Mulder, sensing their displeasure, loves to rub it in.

At flat track racing and road racing, Mulder was never better than average. When he discovered he could not win, he lost interest. He did have some unique problems. One of them was his size. At six feet, 185 pounds, he was and is a moose. During the Big Bear Run, while bouncing through gullies and over the top of rock canyons, Mulder could strong-arm his way past lesser men. But on the super-fast mile and half-mile ovals, competing against riders much smaller and lighter than himself, the lighter riders calmly waited for a straightaway and then sped past him. The 500-cc bikes of this period simply would not pull Eddie along fast enough.

Mentally, Mulder never was happy on the devouring oval tracks. His father considered them dangerous and did not want him racing on them at all. He missed having brakes to slow down with: “Riding without brakes is too hairy. You can compare it to eyesight. You can get used to not having it, but it takes a long time.” The one time in his life he was ever scared, Mulder adds, was when he lost control at 110 mph on the Sacramento mile and was thrown over the handlebars onto the track. He slid on his back for 50 feet, thought he had stopped sliding, and stood up. But he still was traveling 30 mph and was thrown down face-first again, like a drunk.

In all his years of racing, Mulder has never broken or fractured a single bone. As he has had his share of shattering crashes—such as this endo at Sacramento—this must be some indication that he has sturdy bones indeed.

Though he enjoyed road racing on the paved tracks like Meadowdale, 111., and Daytona, he was never really comfortable on pavement. His years in the desert had taught him to skid a bike around corners. But in road racing, where today’s high-adhesive racing tires stick like glue, there is very little skidding. “It was always weird for me to believe,” Mulder says, “that tires could stick that good while you’re going so fast.”

Last year he approached two of his Hollywood friends, the dirt-riding stuntmen Bud Ekins and Bob Harris, and wondered aloud if they could find him some work; he needed the money. Since then, Mulder has worked steadily in the movies and also has done some television shots. He is on his way to a lucrative career as a Hollywood stuntman, if he so chooses. “It’s weird,” he says, using one of his favorite words. “All my life I’ve used my instincts not to fall while I’m racing. Now falling and crashing are the only thing I’m supposed to do.” For his very first stunt he had to wire open the throttle of a Harley chopper, then stand up in the saddle, like a bareback horse rider, while 13 real Hell’s Angels paraded behind him in the street. Mulder said later he was not worried about getting hurt falling, but he knew that if he had fallen, the Angels would have ridden right over him. Shortly afterwards he was paid $450 for plunging off the highway and doing an endo at 80.

“People say I’m crazy,” Mulder says. “You know why? Because I like to do stuff different.” And, “You aren’t born to do just one thing. There are lots of things to do. The world could blow up tomorrow.”

His stunt work is highly profitable. Instead of becoming the No. 1 racer he may become the No. 1 stuntman. What is especially ironic is that he could end up making five times the money in stunt work that he ever could racing motorcycles.

Mulder still races occasionally. He prefers the fuel-burning European-style speedway bikes, the Essos and Japs. (“You can slide the hell out of them. And it’s nearly impossible to crash one.”) Before the races were cancelled two years ago, Mulder went virtually undefeated at the night short-track races indoors at the Long Beach arena. And he has a definite knack for racing on the tiny, eighth-mile, cushion tracks.

He still races for Triumph, but not full-time; Montesa also has him under contract. Triumph now has a love affair going with Gary Nixon, Gene Romero, Van Leeuwen, and a few others. Mulder is no longer one of the elite. Much of the time he is accompanied to the races by an 18-year-old rider named John Hately. Hately’s father used to prepare racing bikes for Eddie. Hately is shy, slender, and has long blond hair that gives him something of an angelic look. The rub is that he is a completely fearless kid who was racing 60-horsepower speedway bikes when he was only 15. Eddie looks at young Hately, whom he calls “Little John,” with affection; he will, he says, tutor him. When he retires from racing, he plans to give Little John his National number, 12. Does 18-year-old Little John evoke memories of an 18-year-old Eddie Mulder? “Of course,” says Mulder. “We are exactly alike. Little John wants to race, wants to really get it on, which I can understand.” In the recent Mint 400 across the Las Vegas desert the two shared a Montesa and finished 9th.

When he was at the peak of his racing career in 1966, Mulder earned $28,000. He blew it all, he says happily. He does not have a plug nickel to show for it.

“I live for the right now,” he says. “I always have, always will. I’ve never had a full-time job in my life.” Recently he cracked up his pickup on a Los Angeles freeway but says he doesn’t care, the insurance will pay for a new one.

Given the opportunity to relive the past 10 years, would Eddie do anything differently? “Nope. Not one thing,” he says doggedly. “I have had nothing but a good time through it all.”

Incredibly, he does not seem to realize that he may have squandered a gift that other, lesser-talented riders would have given anything for. How many novices have stood in the infield and watched Mulder manhandle his way through traffic, riding brilliantly, and said to themselves, “God, if only I could ride like that . . .”

When Mulder was at the top of his form, as he was that day at Peoria in 1965, as he was when he won Big Bear, he was magic. And you know that he could have had it all, could have been No. 1. But apparently he has given up on all of that.

“In addition to talent,” says a key man in the Triumph racing department, “a rider must believe in himself. I’m not sure Eddie does.”

One of the countermen at Triumph of Burbank, Mulder’s favorite hangout for the last decade, asked a magazine writer, hopefully, “Are you going to do a story about the comeback of Eddie Mulder?”

What comeback?

Mulder’s desire has ebbed. Apparently he does not want to be the big man who wins all the races. Maybe he never did. Maybe everyone expected too much of child prodigy Eddie Mulder.

Says Pat Owens, one of his former mechanics, “A person can only stay dedicated to racing for a certain number of years. Take Eddie. He rode his first motorcycle when he was eight. He’s raced steadily since he was 15. Now, he’s burned himself out. He has two children. All of a sudden it’s come home to him that there are other things in life than motorcycles and racing.”

Kim Kimball of Montesa was more succinct: “You can spend all the time you want trying, but you will not be able to understand Eddie. Only Eddie understands Eddie.”

Mulder’s oldest fan, his staunchest fan, finds it impossible to understand Eddie at all. “I don’t know why Eddie gave it all up,” AÍ Mulder says. “I really don’t know.” [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1970 -

Special Feature

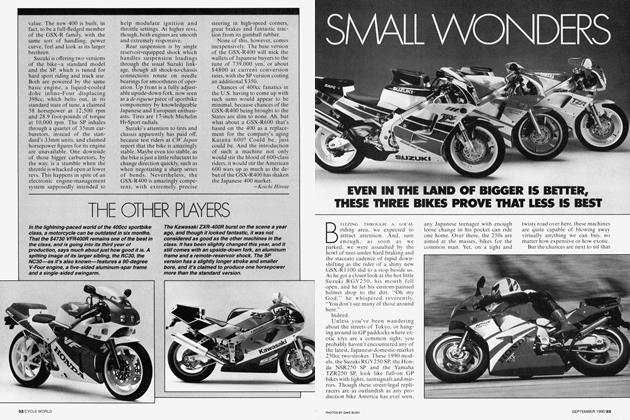

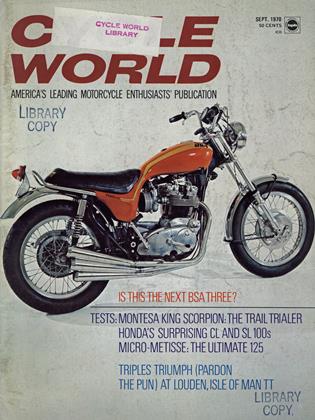

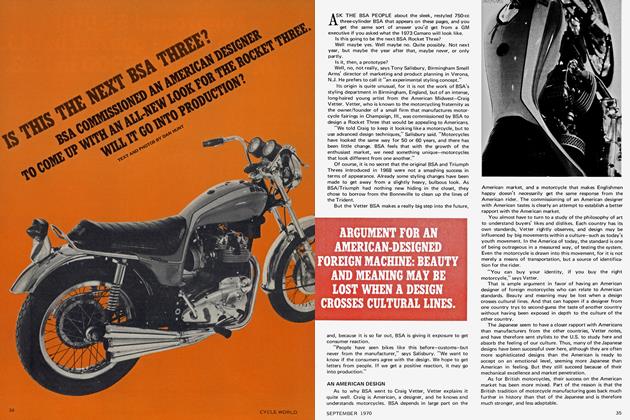

Special FeatureIs This the Next Bsa Three?

September 1970 By Dan Hunt -

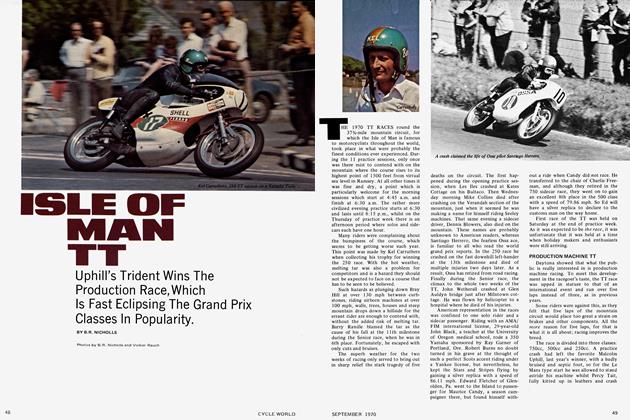

Competition

CompetitionIsle of Man Tt

September 1970 By B.R. Nicholls