High, Flyin Barry Sheene

Rocketship riding and a Jet Set social life got SuperSheene's racing career off the ground.

Joe Scalzo

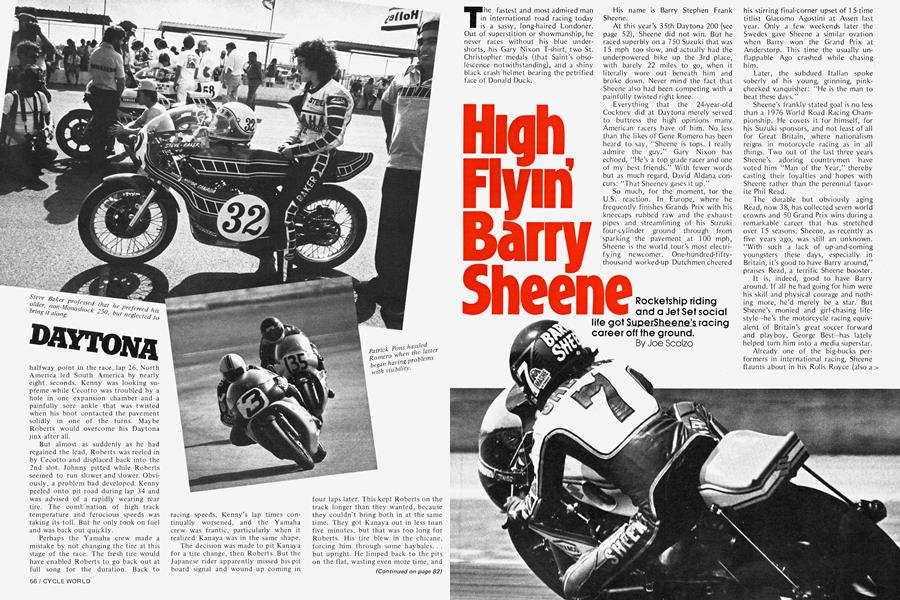

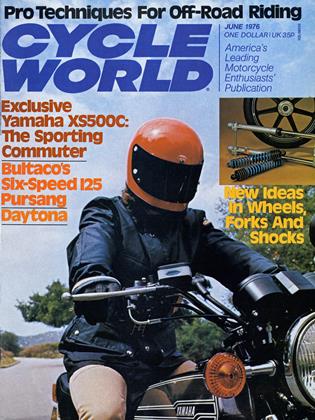

Ihe fastest and most admired man in international road racing today is a sassy, long-haired Londoner. Out of superstition or showmanship, he never races without his blue under-shorts, his Gary Nixon T-shirt, two St. Christopher medals (that Saint's obso-lescence notwithstanding), and a shiny black crash helmet bearing the petrified face of Donald Duck. His name is Barry Stephen Frank Sheene.

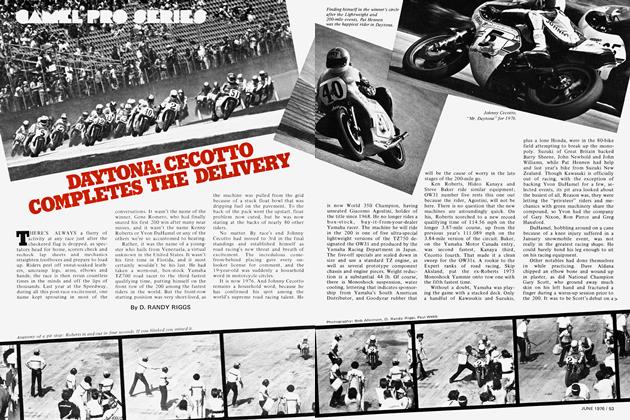

At this year's 35th Daytona 200 (see page 52), Sheene did not win. But he raced superbly on a 750 Suzuki that was 1 5 mph too slow, and actually had the underpowered bike up the 3rd place, with barely 22 miles to go, when it literally wore out beneath him and broke down. Never mind the fact that Sheene also had been competing with a painfully twisted right knee.

Everything that the 24-year-old Cockney did at Daytona merely served to buttress the high opinions many American racers have of him. No less than the likes of Gene Romero has been heard to say, "Sheene is tops. I really admire the guy." Gary Nixon has echoed, "He's a top grade racer and one of my best friends." With fewer words but as much regard, David Aldana con curs: "That Sheeney gases it up." So much, for the moment, for the U.S. reaction. In Europe, where he frequently finishes Grands Prix with his kneecaps rubbed raw and the exhaust pipes and streamlining of his Suzuki four-cylinder ground through from sparking the pavement at 1 00 mph, Sheene is the world tour's most electri fy i ng newcomer. One-hun dred-fifty thousand worked-up Dutchmen cheered

his stirriag final-corner upset of 1 5-time titlist Giacomo Agostini at Assen last year. Only a few weekends later the Swedes gave Sheene a similar ovation when Barry won the Grand Prix at Anderstorp. This time the usually un flappable Ago crashed while chasing him.

Later, the subdued Italian spoke soberly of his young, grinning, pink cheeked vanquisher: "He is the man to beat these days."

Sheene's frankly stated goal is no less than a 1976 World Road Racing Cham pionship. He covets it for himself, for his Suzuki sponsors, and not least of all for Great Britain, where nationalism reigns in motorcycle racing as in all things. Two out of the last three years Sheene's adoring countrymen have voted him "Man of the Year," thereby casting their loyalties and hopes with Sheene rather than the perennial favor ite Phil Read.

The durable but obviously aging Read, now 38, has collected seven world crowns and 50 Grand Prix wins during a remarkable career that has stretched over 1 5 seasons. Sheene, as recently as five years ago, was still an unknown. "With such a lack of up-and-coming youngsters these days, especially in Britain, it's good to have Barry around," praises Read, a terrific Sheene booster.

It is, indeed, good to have Barry around. If all he had going for him were his skill and physical courage and noth ing more, he'd merely be a star. But Sheene's monied and girl-chasing life style-he's the motorcycle racing equiv alent of Britain's great soccer forward and playboy, George Best-has lately helped turn him into a media superstar. Already one of the big-bucks per formers in international racing, Sheene flaunts about in his Rolls Royce (also a Jensen Interceptor, Daimler, Ford Granada and Mercedes), lets no one else touch scissors to his hair except Vidal Sassoon, wears a $600 French watch made of gold, buys only the latest, most “In” clothing, and seems never to lack fresh and beautiful young ladies to hang on his arm or arms, no matter the country in which he’s racing.

Sheene

Jet Set behavior such as this, coupled with Sheene’s dashing, dangerous profession, has caught the eye of the general press as well as the racing one. Sheene in 1975 was booked onto eight different British TV talk shows, an incredible number for a motorcycle racer. A BBC documentary on his life, built around his infamous Daytona crash of a year ago, attracted huge audiences all over Europe. This past March a major London newspaper sent a correspondent all the way to Florida to document Sheene’s every move during Speedweek. Rolls Royce even lent him a spare Silver Shadow to get around town.

Impressive as all this is, it’s not the reason that Romero, Nixon, Aldana and other domestic racers have adopted Barry Sheene as one of their own. Americans have done so because Sheene is in possession of a quality that they can identify with and admire: namely, a total dedication to motorcycle racing that is as awesome and unshakable as their own.

Sheene’s six-foot tall body is a virtual road map of racing scars. It’s not the scars themselves that are so impressive, but the fact that Sheene is still racing at all after living through, in 1975, the worst Daytona crash in recent memory. It was the fastest too.

During a practice run, his 750 Suzuki was making 175 mph—all it had in it—when a rear tire blew out. In his biography, Super Sheene, Barry described it thusly:

“The bike turned completely sideways and I went right out of controlup the banking, down the banking, and then it spat me straight over the top.”

As he tumbled to a stop after rolling along the banking for some 825 feet, he mechanically began checking himself out for injuries before help arrived.

“My right leg was tucked round at 90 degrees to my body, so I knew I had broken that. I knew I had broken my arm and shoulder. I went to take off my glove, and my wrist was bending three inches above where it should bend, so I knew that was broken as well. My collarbone was digging into my throat so that was another broken bone. My chest hurt a lot and I couldn’t breathe too well. I thought I may have punctured a lung.”

Sheene’s self-diagnosis turned out to be remarkably accurate and almost complete. But, in addition, he’d fractured some ribs, thrown out his back, and had so much skin dragged off that his kidneys were bleeding internally. Later he insisted that if it hadn’t been for the badly broken leg, he’d still have been able to race in the 200 miles.

Not once during his subsequent convalescence period did Sheene profess dismay, fright, or leave any doubt about his resuming racing quickly. The only thing he intended changing, he remarked wryly, was tire companies.

Following a round of operations in America, Barry was sent home to his country estate 70 miles from London. A parade of expensive doctors and specialists arrived to administer to him, including one technician who provided daily electric shock treatments to burn excess calcium off his swollen left knee joint.

Four and a half weeks after the crash he was doing push-ups to strengthen his collarbone, and hand-squeezes to tone up the muscles. After five weeks he was out of the house and limping about, and pedaling a bicycle around the neighborhood.

Seven weeks after fracturing his right leg, smashing his left thigh, right wrist, four ribs, collarbone and three back vertebrae, Barry Sheene took the green flag with the rest of the riders at the Cadwell Park track. Fie only lasted for 10 laps before pain stopped him, but he’d been in the lead that entire time.

Later he went to the Grand Prix of Austria at the Salzburgring and qualified among the leaders. Race organizers were immediately apprehensive. Believing it impossible for Sheene to be fit, they rousted him out of bed at eight a.m. Sunday morning and dragged him off to be examined by their own doctor. Still unsatisfied when the doctor approved Sheene, the Austrians made him demonstrate that he could bump-start his bike.

Sheene did. Even so, moments before the start of the race, stewards pulled his Suzuki off the starting line and the race went off without him. “They certainly didn’t want me in their Grand Prix,” Sheene commented a bit petulantly.

He went on to win two of the eight remaining Grands Prix, even taking time off from the world tour to occasionally compete in England. At Brands Hatch he won four races and established a new lap record during a single searing afternoon.

All in all a brilliant comeback. But Sheene was bitterly disappointed to finish 1975 ranked no better than 6th in the world when he’d wanted no less than a Championship.

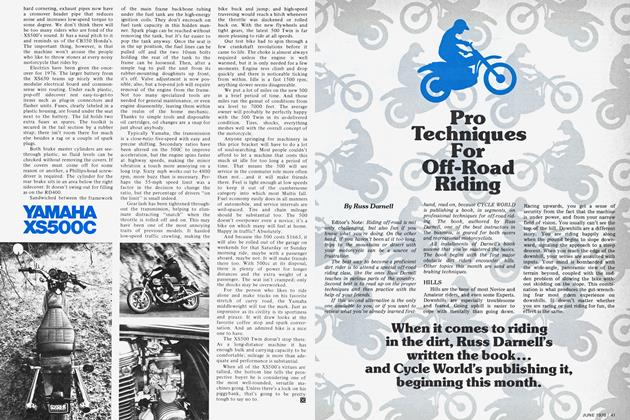

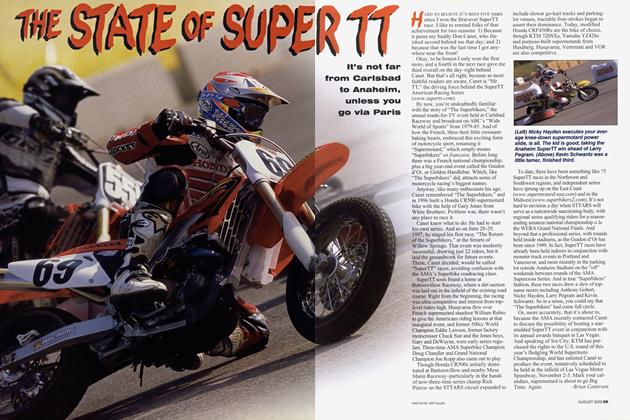

Sheene flat out on the back of a thundering G.P. bike is all arms, elbows and flapping knees as he hurtles into hairpins heeled over at gravity-defying angles. A classic knee-dragger [a la his racing brother-in-law, Paul Smart), he clipped one knee on a Mallory Park curbing last fall and the resultant broken leg temporarily put him back in the hospital.

Mallory Park, Brands Hatch and Oulton Park are kinking, undulating, thoroughly breathless road courses, requiring skill, nerve and discipline. Unlike most American tracks, there are solid objects to hit when a motorcycle leaves the pavement.

Sheene’s racing was practically formed on such unforgiving circuits. They taught him to “Get past other riders any way you can, stick a wheel inside or outside—just do it.” Last year at Mallory in the meet the British call The Race of the Year, he blazed his Suzuki through a pack that included Read, Agostini, Yvon DuHamel and Aldana. It was a 40-mile sprint conducted in both sunshine and rain, and by the finish Sheene was so far in the lead that he’d lapped all but the top five. His closest pursuer, Aldana, was a whopping 14 sec.—a third of a lap— behind.

Sheene is at his boldest and most fearless when racing in World Championship events on the Continent. At Spa in mountainous Southern Belgiumeight fantastic miles of normal backcountry roads—Sheene lapped at a world record 135.75 mph. His Suzuki later seized at top revs on the Massta Straight, but he just got a hand on the clutch before the rear tire locked. His speed at the time was in the neighborhood of 180 mph. The experience, like the Daytona one, did not appear to unnerve him.

For being who he is and doing what he does, Barry Sheene is handsomely compensated, earning as much as $100,000 a year in salary from Suzuki. There’re also outside product endorsements and $6000 or more per race in starting money. This is reportedly more than any other rider gets.

Suzuki owes the young Englishman a great deal. He continued racing the new and temperamental four-cylinder G.P. bike during 1974 despite chronic gearbox trouble that brought Sheene off at high speed in Italy and Sweden. Though almost ready to quit the troublesome mount, he continued believing in its potential and speed.

All his faith was rewarded last summer in Holland. Sheene can still talk for hours about beating Agostini in the Dutch G.P., which resulted in the closest finish in 27 years of world class racing.

In the early laps Sheene was dogging Agostini’s leading Yamaha so fiercely in the bends that the flustered Italian had both wheels skidding and his exhaust pipes grinding and pounding the pavement. Then, with one lap to go, Sheene fell several motorcycle lengths behind the World Champion. Summoning every drop of skill, courage and horsepower at his disposal, Sheene attacked and sent his big Suzuki hurtling over the final 4.78 miles of curving macadam road.

Riding like a madman, he broke the old track record by four seconds. He didn’t have his front wheel ahead of Agostini until a foot before the checkered, he’d timed matters that closely.

A self-assured young man, Barry Sheene knows exactly where he has been and where he is going. He’s allotted himself 10 more years to bring World Championships to Britain. By then he’ll be 35, in all probability a millionaire, and ready for a full-time playboy’s life in Bermuda and the sun.

“It may be the Muhammed Ali type of thing to say,” he remarked recently, “but I can ride as well as Giacomo Agostini or Phil Read or anyone. And all I need now is for Suzuki to have luck with the bikes, and we have a World Championship.”

Sheene’s rise to motorcycle racing superstardom was not meteoric. He entered his first race at age 17 and four years later he was still learning the basics on underpowered 125cc bikes belonging to his father Frank “Franko” Sheene, a middling club racer from the ’50s. Not until 1973, when Suzuki of Great Britain signed him, was Sheene able to fully demonstrate the wonders he could work with 100 screaming horses under him.

As a youngster, Sheene’s father once said, Barry was a cheeky lad, continually berating the older riders—some of them famous—that Franko sponsored. The boy brashly proclaimed that he could do a far better job racing Dad’s motors than they could. Franko now readily admits that Barry was right on that score. |§j

View Full Issue

View Full Issue