CAMEL PRO SERIES

DAYTONA: CECOTTO COMPLETES THE DELIVERY

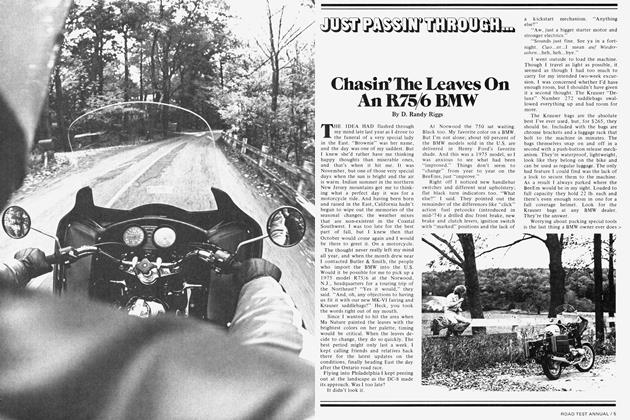

D. RANDY RIGGS

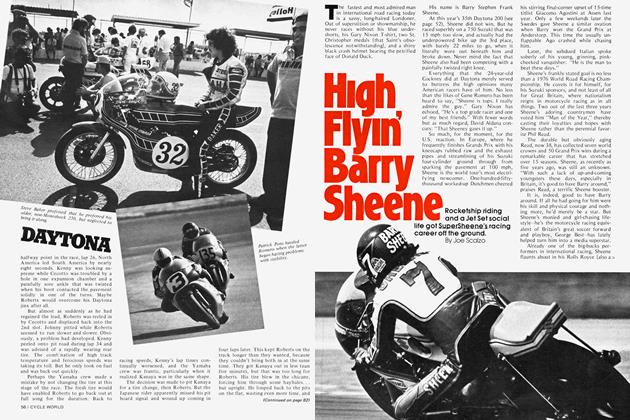

THERE'S ALWAYS a flurry of activity at any race just after the checkered flag is dropped, as spec-tators head for home, scorers check and recheck lap sheets and mechanics straighten toolboxes and prepare to load up. Riders peel off sweat-soaked leath-ers, uncramp legs, arms, elbows and hands; the race is then rerun countless times in the minds and off the lips of thousands. Last year at the Speedway, during all this post-race excitement, one name kept sprouting in most of the conversations. It wasn't the name of the winner, Gene Romero, who had finally snared his first 200 win after many near misses, and it wasn't the name Kenny Roberts or Yvon DuHamel or any of the others we're so accustomed to hearing.

Rather, it was the name of a young ster who hails from Venezuela, a virtual unknown in the United States. It wasn't his first time in Florida, and it most certainly wouldn't be his last. He had taken a worn-out, box-stock Yamaha TZ700 road racer to the third fastest qualifying time, putting himself on the front row of the 200 among the fastest riders in the world. But the front-row starting position was very short-lived, as

the machine was pulled from the grid because of a stuck float bowl that was dripping fuel on the pavement. To the back of the pack went the upstart, float problem now cured, but he was now staring at the backs of nearly 80 other riders.

No matter. By race's end Johnny Cecotto had moved to 3rd in the final standings and established himself as road racing's new threat and breath of excitement. The incredulous come from-behind placing gave every on looker license for comment, and the 19-year-old was suddenly a household word in motorcycle circles.

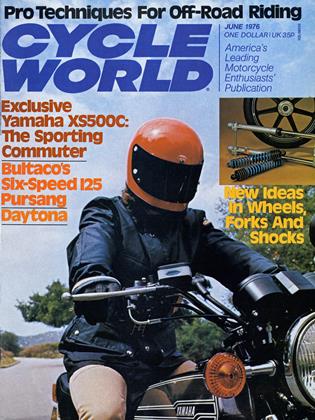

It is now 1 976. And Johnny Cecotto remains a household word, because he has confirmed his spot among the world's supreme road racing talent. He is now World 350 Champion, having unseated Giacomo Agostini, holder of the title since 1 968. He no longer rides a box-stock, buy-it-from-your-dealer Yamaha racer. The machine he will ride in the 200 is one of five ultra-special lightweight versions of the TZ750 de signated the 031. and produced by the Yamaha Racing Department in Japan. The five-off specials are scaled down in size and use a standard TZ engine, as well as several prototype component chassis and engine pieces. Weight reduc tion is a substantial 44 lb. Of course, there is Monoshock suspension, water cooling, lettering that indicates sponsor ship from Yamaha's South American Distributor, and Goodyear rubber that will be the cause of worry in the late stages of the 200-mile go.

Ken Roberts, Hideo Kanaya and Steve Baker ride similar equipment; OW31 number five rests this one out because the rider, Agostini, will not be here. There is no question that the new machines are astoundingly quick. On his, Roberts scorched to a new record qualifying time of 114.56 mph on the longer 3.87-mile course, up from the previous year’s 1 11.089 mph on the 3.84-mile version of the circuit. Baker, on the Yamaha Motor Canada entry, was second fastest, Kanaya third, Cecotto fourth. That made it a clean sweep for the OW31s. A rookie to the Expert ranks of road racing, Skip Aksland, put the ex-Roberts 1975 Monoshock Yammie onto row one with the fifth fastest time.

Without a doubt, Yamaha was playing the game with a stacked deck. Only a handful of Kawasakis and Suzukis, plus a lone Honda, were in the 80-bike field attempting to break up the monopoly. Suzuki of Great Britain backed Barry Sheene, John Newbold and John Williams, while Pat Hennen had help and last year’s bike from Suzuki New Zealand. Though Kawasaki is officially out of racing, with the exception of backing Yvon DuHamel for a few, selected events, its pit area looked about the busiest of all. Reason was, they were letting the “privateer” riders and mechanics with green machinery share the compound, so Yvon had the company of Gary Nixon, Ron Pierce and Greg Hansford.

DuHamel, hobbling around on a cane because of a knee injury suffered in a January snowmobile event, was not really in the greatest racing shape. He could barely bend his leg enough to sit on his racing equipment.

Other notables had done themselves in while practicing. Dave Aldana chipped an elbow bone and wound up in plaster, as did National Champion Gary Scott, who ground away much skin on his left hand and fractured a finger during a warm-up session prior to the 200. It was to be Scott’s debut on a Yamaha TZ750 Four.

Rain clouds threatened for a time a few hours shy of the race, worrying many foreign riders who had commitments in Europe the next weekend and couldn’t be around for a rescheduling. But winds carried away the ominous puffs, and when the sky cleared, temperatures rose. The stiff breeze would play havoc with many of the riders, who were already fighting the fatigue of 200 racing miles and strong G-forces on the oval’s banking.

DAYTONA 200

The three-wave start, with 80 riders and bikes getting underway, is ferocious from any angle, and dowright scary if you happen to be standing in close proximity to the grid. Cecotto had the initial jump, but lost ground as he rolled off the throttle to control a spectacular sky-shot wheelie. Pat Evans was 1st into the infield with the crew of Roberts, Cecotto, Baker and Kanaya trailing. The heavy company must have gotten to Evans, because he let Roberts by in the chicane and then crashed in a cloud of dust as the first wave entered turn one. He was not injured.

Steve Baker had figured on Roberts and Cecotto, and perhaps Kanaya, to put on a fairly hard dice for the lead in the early stages. His plan was to hold back and cruise, keeping them always in sight and conserving his red and black Yamaha while they did the charging. The plan looked as though it were working.

Roberts and Cecotto were streaking along at a tough pace. Baker watched the action while holding 3rd; Kanaya had his sights fixed on Baker. It was the Japanese star’s first ride at Daytona since crashing here two years ago and putting himself out of action for quite some time. He has since tried to tame his reputation as a spiller, and there is no question that he has talent.

Sorting themselves out behind the front-running crew were Greg Hansford, Gary Nixon, Gene Romero, Steve McLaughlin, Barry Sheene and Skip Aksland. Lapping started even before 10 laps were down and in some instances the passing methods were on the hairy side. Part of the problem was the great speed differential between the front runners and the back markers; both groups worry much about what the others are up to.

Seven times World Champion Phil Read looked to be down on power and pitted early to replace a blown radiator hose. He lost the greater part of a lap in the process and later dropped out with an engine seizure, possibly caused by pouring cold water into the overheated engine on the earlier stop.

Steve Baker was the next rider to have the uglies hit. His Bob Worldprepared Four suddenly turned into a Three and Baker suspected a fouled plug. Running a full lap with one cylinder dead to see if it would clear out, Baker lost some ground before pitting on lap 10. After a frantic plug change, the engine refused to go back on all four. Steve, one of racing’s most humble and brilliant stars, reluctantly climbed off his machine and strode to the pits. “What a bummer. . .I’m really gonna be mad about this later on after I think about it a while.” Who wouldn’t be? The problem may have been caused by a seized cylinder.

Nearing lap 15, pit stops for fuel were on each rider’s agenda. Confusion reigned in the Yamaha pits as Cecotto and Roberts pitted at the same time and came close to hitting one another. Back on the track Cecotto went into the lead, but Kenny stuck close behind and kept the pressure on. Average speed was up to 108 mph and more as Kanaya tried to keep the two leaders in sight. Two green machines were some distance back holding 4th and 5th, but that didn't last long. The Kawasaki of Hansford quit, moving Nixon up a notch, with Barry Sheene breathing down his vestibule. Gary was Kawasaki's only hope at this point, since Yvon was well back and circulating off the pace with broken expansion chambers. The remainder of Team Green had already parked on pit road.

And then many began wondering. . .“Wow, Nixon is in 4th. . .wouldn’t it be something if. . .?” No doubt about it, Gary had the hopes and wishes of many riding right along with him, and the momentum was carrying him upward in the tabulations. Up front, Roberts apparently decided it was time to make his move to return to first and keep it from there on out; by the halfway point in the race, lap 26, North America led South America by nearly eight seconds. Kenny was looking su preme while Cecotto was troubled by a hole in one expansion chamber and a painfully sore ankle that was twisted when his boot contacted the pavement solidly in one of the turns. Maybe Roberts would overcome his Daytona jinx after all.

DAYTONA

But almost as suddenly as he had regained the lead, Roberts was reeled in by Cecotto and displaced back into the 2nd slot. Johnny pitted while Roberts seemed to run slower and slower. Obviously, a problem had developed. Kenny peeled onto pit road during lap 34 and was advised of a rapidly wearing rear tire. The combination of high track temperature and ferocious speeds was taking its toll. But he only took on fuel and was back out quickly.

Perhaps the Yamaha crew made a mistake by not changing the tire at this stage of the race. The fresh tire would have enabled Roberts to go back out at full song for the duration. Back to racing speeds, Kenny’s lap times continually worsened, and the Yamaha crew was frantic, particularly when it realized Kanaya was in the same shape.

The decision was made to pit Kanaya for a tire change, then Roberts. But the Japanese rider apparently missed his pit board signal and wound up coming in four laps later. This kept Roberts on the track longer than they wanted, because they couldn’t bring both in at the same time. They got Kanaya out in less tnan five minutes, but that was too long for Roberts. His tire blew in the chicane, forcing him through some haybales. . . but upright. He limped back to the pits on the flat, wasting even more time, and his race for the win was over. With a fresh tire in place, Kenny’s only choice at that late point in the event was to try to salvage a top ten placing. And that doesn’t count very heavily in Kenny’s book.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 56

The stops for tires moved up Nixon and Sheene, and Hennen’s number 40 now glowed on the lighted position board in the infield. Worrisome looks appeared on the faces of the Venemotos C.A. pit crew as they speculated on Cecotto’s tire condition and Goodyear advised an eyeball check of the situation. But Cecotto was already tasting sweet victory; he could have bowled his way past wall-to-wall NASCAR Stockers at that point.

Suzuki G.B.’s smile turned to questioning frowns as Sheene’s and Newbold’s machinery ground to separate halts in the infield. Sheene had been in 3rd, Newbold 10th. They had traveled a long way for misery. Romero, riding a Don Vesco Yamaha, moved up along with Pat Hennen. Romero’s windscreen and faceshield were being splashed with fuel spouting from a cracked fuel vent casting on the tank. The lack of decent visibility held him to a pace slower than he would’ve liked. Behind Romero, Patrick Pons and Michel Rougerie from France were running 5th and 6th, their best Daytona showings yet.

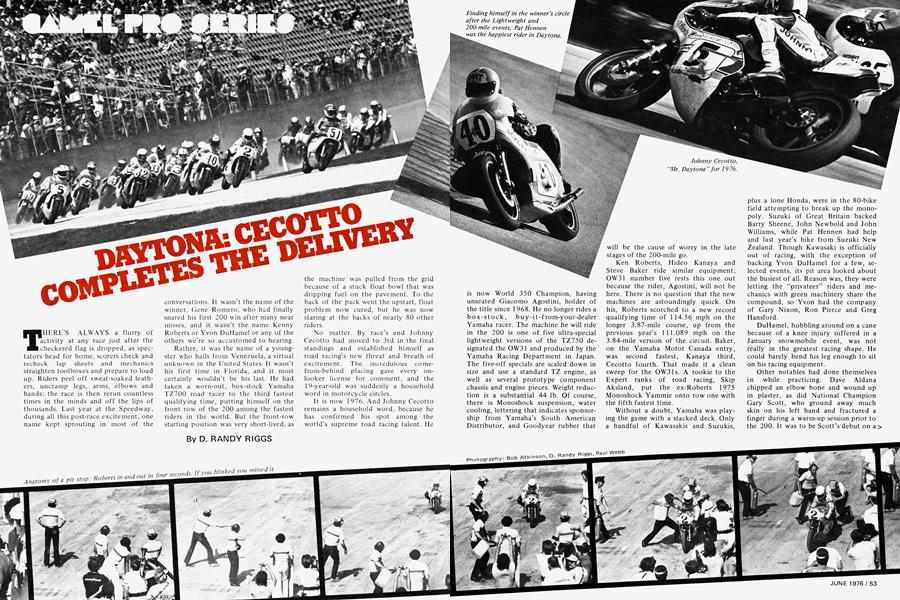

One look at Cecotto’s pit area was enough to tell anyone where he was about to finish, and at the wave of the checkered Cecotto delivered the victory, a fulfillment of an unspoken promise. The fuel tank was nearly empty, the rear tire showed the whites of the cords. A hole was ground in one expansion chamber. But Cecotto himself looked a lot less ragged than the machine as he tried to explain in broken English about some of his problems during the race.

The green “privateer” Kawasaki prepared by Irv Kanemoto and ridden by Gary Nixon was a delightful sight in victory circle. Though down on speed, Gary qualified the bike tenth fastest and rode a consistent race, despite being hampered by a slippery rear tire in the late stages and the lack of a tach after the first fuel stop. It’s not hard to figure out why Gary is everyone’s superhero, his finishing 2nd here did a lot of people’s hearts good.

With a Yamaha and a Kawasaki in 1st and 2nd, it was only fitting that a big Suzuki Triple fill in the 3rd slot. Pat Hennen rode it, capping a perfect weekend. No one noticed him until the laps were well counted down and he was there when it mattered. Hennen was one of the team members out of a ride when U.S. Suzuki decided to pull its support out of road racing to concentrate on motocross. It's both ironic and amusing to note that this was Suzuki's first trip into Daytona's winner circle since 1 969. And all it took was a "private" ex-fac tory machine with an ex-factory rider to do what they had been after for so long. It was things such as this that made the 1976 event the best Daytona 200 ever.

100-MILE INTERNATIONAL LIGHTWEIGHT

In what has traditionally been a Yamaha fracas, the 250cc Lightweight event had some new prestige added this year, thanks to a bit of international flavor. The Experts-only affair had 35 foreign entries among the group, with promise of stiff competition for the regulars, most of whom were on Yamahas. Just six Kawasakis and eight Harley-Davidsons were out to break the Lightweight Yamaha grip, and the way things were looking after five-lap qualifying races, a victory by a non-Yamaha machine loomed as a possibility.

Ron Pierce put his 250 Kawasaki onto the pole by virtue of the fastest heat race time. He was joined by Steve Baker and Roberts on the new Monoshock 250s, Phil McDonald on a K&N Yamaha and Pat Hennen on a threeyear-old Harry Hunt machine.

Some felt that Roberts was sandbagging, because his mastery of the 250s wasn’t really showing in practice or the heat. The cause was said to be horsepower, but when it came time to go racing in the final, Roberts had found all he needed. Though he diced with Baker and Hennen, as well as with Pierce for several laps, there was no question as to his superiority when he decided to went.. In fact, at one point he turned around and waved for Baker and Hennen to come up and race, then once again disappeared at will.

Aside from Pierce’s Kawasaki, no alien brands threatened the Yamaha stronghold once the race was well underway. Nixon’s bike expired, as did Jay Springsteen’s H-D; fiesty Greg Sassaman was the first non-Yamaha rider to show on the lap charts with his H-D. And it wasn’t fast enough to sneak him into the top twenty.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 83

When Pierce crashed on lap 19 of the 26-lap go, it sewed up a Yamaha sweep. Roberts went unchallenged at the flag, and Hennen held off Baker’s new machine with the flawless Harry Hunt “oldie.” Back some distance, Kanaya and Doug Teague were having a race of their own for 4th, with Kanaya prevailing on the last lap.

With an overall race average of more than 100 mph, no one can call the 250s “kid stuff.”

50-MILE SUPERBIKE PRODUCTION

The term “production” according to the AMA definition has become a joke for 1976 racing. The 0 to 400cc class was dropped (probably because the AMA got wind of the fact that people were actually going road racing for under $1000), and the Open class was established with a new lOOOcc limit. Rules were written for just about any

kind of interpretation, meaning Superbike Production is now the “Run What You Brung” class in AMA road racing.

Butler & Smith surprised the troops with three exotic BMW R90 Sports for Reg Pridmore, Gary Fisher and Steve McLaughlin. The trio of machines prepared by the outlet’s Eastern headquarters sported Michelin slicks, lOOOccs, Koni monoshock suspension and trick everything. The more one looked at the bikes, the more one saw that was anything but production. The R90s were flawless and begged to be appreciated by anyone within sight. It was in reality the first full-on factory effort for AMA production racing.

Besides the BMWs, there were other threats from potential winners. The Cook Neilson Ducati Desmo prepared by Phil Shilling had the fastest speed in the traps, and was getting around right smartly. It, too, bears little resemblance to a run-of-the-mill Ducati SS, if one can call such a machine run-of-the-mill even in stock form, and it was displacing 883cc, up from the normal 750. Monstrous tires, bellowing exhausts, oil coolers and rumpety-rump idles gave broad hints as to what these motorcycles really were.

The story of what happened to the normally top-gun, king of the class Dale-Starr Kawasaki can be found on page 72 of this issue. But a Yoshimura Kaw 1000 ridden by Wes Cooley was doing its best to uphold the marque’s tradition in this very fast racing class.

Cook knew he had to try and get his Ducati out in front at the start and did just that when the flag went down. But the Beemer group tucked in right behind and from that point on the fans were treated to 50 miles of throttle-tothe stops racing. A new and rare Moto Guzzi 850 LeMans with Mike Baldwin steering was making a heck of an impression, finally settling into a comfortable 5th for the remainder of the event. Lead changes were happening in every corner, and it was difficult to expect anything but a 1-2-3 BMW finish.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 85

But not far from the end Fisher’s machine broke a rocker arm and dropped out, leaving 3rd to Cook, who would’ve been ready to take advantage of any bobble the leaders might succumb to. At the finish it was Steve. . . no, Reg. Well, maybe Steve after all. . . though it sure could’ve been Reg. It was that close. The trackside camera told the story, however, and it was Steve. . . by a whisker.

76-MILE NOVICE

Three riders—Tom Berry, Harry Klinzman and Ed Ingram-dueled for a goodly portion of the Novice final, but privateer Ingram from Pennsylvania had a surprise for the two Southern Californians at the end. Berry, an Expert dirt tracker, grabbed an early “follow me,” but was slowed when the machine dropped a couple thousand rpm. Ingram took over but was pursued relentlessly by Klinzman most of the way. Harry would just about catch up and then encounter slower traffic; the gap was never shortened enough. The SoCal hotshoe was also bothered by a runny nose and simply had to settle for 2nd behind a deserving and surprised Ed Ingram. |<5]

DAYTONA 200