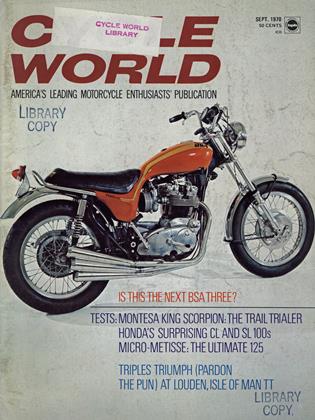

IS THIS THE NEXT BSA THREE?

BSA COMMISSIONED AN AMERICAN DESIGNER TO COME UP WITH AN ALL-NEW LOOK FOR THE ROCKET THREE WILL IT GO INTO PRODUCTION?

DAN HUNT

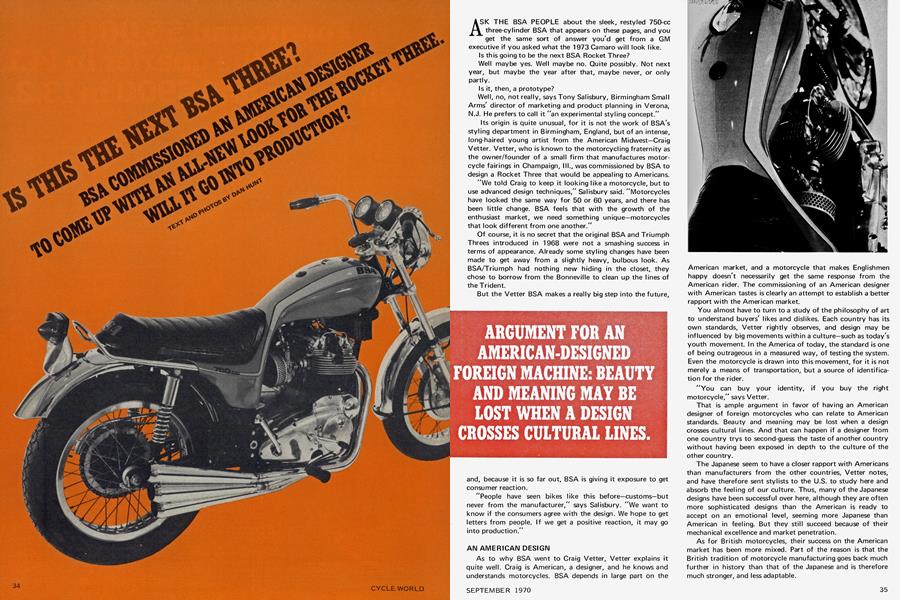

ASK THE BSA PEOPLE about the sleek, restyled 750-cc three-cylinder BSA that appears on these pages, and you get the same sort of answer you'd get from a GM executive if you asked what the 1973 Camaro will look like.

Is this going to be the next BSA Rocket Three?

Well maybe yes. Well maybe no. Quite possibly. Not next year, but maybe the year after that, maybe never, or only partly.

Is it, then, a prototype?

Well, no, not really, says Tony Salisbury, Birmingham Small Arms' director of marketing and product planning in Verona, N.J. He prefers to call it "an experimental styling concept."

Its origin is quite unusual, for it is not the work of BSA's styling department in Birmingham, England, but of an intense, long-haired young artist from the American Midwest—Craig Vetter. Vetter, who is known to the motorcycling fraternity as the owner/founder of a small firm that manufactures motorcycle fairings in Champaign, III., was commissioned by BSA to design a Rocket Three that would be appealing to Americans.

"We told Craig to keep it looking like a motorcycle, but to use advanced design techniques," Salisbury said. "Motorcycles have looked the same way for 50 or 60 years, and there has been little change. BSA feels that with the growth of the enthusiast market, we need something unique—motorcycles that look different from one another."

Of course, it is no secret that the original BSA and Triumph Threes introduced in 1968 were not a smashing success in terms of appearance. Already some styling changes have been made to get away from a slightly heavy, bulbous look. As BSA/Triumph had nothing new hiding in the closet, they chose to borrow from the Bonneville to clean up the lines of the Trident.

But the Vetter BSA makes a really big step into the future, and, because it is so far out, BSA is giving it exposure to get consumer reaction.

ARGUMENT FOR AN AMERICAN-DESIGNED FOREIGN MACHINE: BEAUTY AND MEANING MAY BE LOST WHEN A DESIGN CROSSES CULTURAL LINES.

"People have seen bikes like this before—customs—but never from the manufacturer," says Salisbury. "We want to know if the consumers agree with the design. We hope to get letters from people. If we get a positive reaction, it may go into production."

AN AMERICAN DESIGN

As to why BSA went to Craig Vetter, Vetter explains it quite well. Craig is American, a designer, and he knows and understands motorcycles. BSA depends in large part on the American market, and a motorcycle that makes Englishmen happy doesn't necessarily get the same response from the American rider. The commissioning of an American designer with American tastes is clearly an attempt to establish a better rapport with the American market.

You almost have to turn to a study of the philosophy of art to understand buyers' likes and dislikes. Each country has its own standards, Vetter rightly observes, and design may be influenced by big movements within a culture—such as today's youth movement. In the America of today, the standard is one of being outrageous in a measured way, of testing the system. Even the motorcycle is drawn into this movement, for it is not merely a means of transportation, but a source of identification for the rider.

"You can buy your identity, if you buy the right motorcycle," says Vetter.

That is ample argument in favor of having an American designer of foreign motorcycles who can relate to American standards. Beauty and meaning may be lost when a design crosses cultural lines. And that can happen if a designer from one country trys to second-guess the taste of another country without having been exposed in depth to the culture of the other country.

The Japanese seem to have a closer rapport with Americans than manufacturers from the other countries, Vetter notes, and have therefore sent stylists to the U.S. to study here and absorb the feeling of our culture. Thus, many of the Japanese designs have been successful over here, although they are often more sophisticated designs than the American is ready to accept on an emotional level, seeming more Japanese than American in feeling. But they still succeed because of their mechanical excellence and market penetration.

As for British motorcycles, their success on the American market has been more mixed. Part of the reason is that the British tradition of motorcycle manufacturing goes back much further in history than that of the Japanese and is therefore much stronger, and less adaptable.

THE BONNEVILLE PHENOMENON

One notable success in America has been the Triumph Bonneville. Vetter feels that Americans accept it as a goodlooking bike because it is straightforward, and has simple lines. While this is true, one should look further than that.

The Bonneville appeals to the American mind, because it has been around so long that it has become American. Certainly the British made no conscious effort to design an “American” bike when they introduced the Bonneville. Compared to the earlier Triumph Twins, the Bonneville has an entirely different feeling about it. The early Twins are English, the latest Bonnevilles are American. And the evolution in the Bonnie's appearance has come about in bits and pieces, as the English adjusted its looks from year to year to better suit U.S. taste.

When the Rocket Three was introduced, an entirely new situation developed. The designers at BSA had to style a motorcycle from scratch. Naturally, it came out looking like an English motorcycle, or, as Vetter would put it, “Almost rocky, and clubby. You can see the lines of the Three in English cars, like the old MGs.”

CHOPPER DESIGN IS IMPORTANT TO VETTER, THE UNDERGROUND FOR FUTURE MOTORCYCLE STYLING.

The Rocket Three, in fact, is rather automotive in appearance. It has an enclosed look and the powerplant seems hidden. The metal surfaces have stamped-in styling lines, and the effect is complex.

In approaching the new design for the BSA Three, Vetter sought to articulate two of his basic beliefs about motorcycles. Motorcycles are by nature simple. And it is inherent in a motorcycle's nature that the chassis and engine parts are visible.

It is evident that Vetter has been profoundly influenced by the chopper movement in this country and sees it as part of the vanguard of American taste. Movements that are taken up by the whole country start in the underground, usually with youth—like today's free-swinging clothes and rock music. The chopper craze to him is important, for it is the underground for future motorcycle styling, even in its excesses.

"Chopper people recognize, unconsciously, perhaps, the animalness of a motorcycle, its feeling of power. Look at a lion. Deep chest, paws forward, the rear end light. There's something primitive in us that we associate with that and transfer into motorcycles. I think there are some lean animal proportions in some choppers today. Some go too far. But chopper ideas are pointing in some direction. I feel that the BSA is an assimilation of some of these ideas, some of the stimuli around me-it is what's happening today."

VETTER WANTED TO MAKE THE RELATIONSHIP OF MACHINE AND RIDER AS INTIMATE AS POSSIBLE: "ON NO OTHER MACHINE DO YOU ENCIRCLE THE ENGINE WITH YOUR LEGS1".

VETTER'S CONCEPTS EXECUTED

In the BSA, Vetter's conceptions about the basic character of a motorcycle and the archetypal feeling of animal power translate themselves into these guidelines: the front end should be light and airy; the engine section a triangular shape, massive and powerful looking, tapering into a lighter rear. BSA itself wanted the bike to be visually and perhaps mechanically lighter, more rideable looking, and Vetter seems to have succeeded.

Starting with the engine itself, he extended the cylinder head fins an additional 3/4 in. at some points. "The BSA's most exciting feature is its engine, and they tried to make it too compact and hide it away. If anything, you should exaggerate it."

Vetter's attractive polyester resin seat/tank unit, which he feels is an important buffer zone that helps relate the hard lines of the mechanical entity to the soft, human lines of the rider, also helps exaggerate the engine by exposing more of it to view. As he wanted the powerplant to relate graphically to the back wheel, the line of the tank thrusts diagonally downward from above the engine to the rear of the machine. That "buffer zone" is all curves, to better associate with the human shape. Even the seat itself is curved.

"If you look at a bike and rider carefully, there's simply no way you can come up with a flat board seat. It doesn't fit," Vetter said, castigating a raft of Japanese machines in the process.

To produce the necessary light look at the front of the machine, Vetter chose Ceriani-style front forks.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

If this approach sounds too arty, it should be added that Craig's approach to the design of the tank, seat and side panels was governed by practical consideration as well. He felt the original seat was too wide, as was the tank, making it harder for the rider to feel part of the machine, and ride it well. Narrowing things made it necessary to move the coils and oil tank inboard. The oil tank may now be filled by removing the seat, which also reveals a receptacle for a bag of tools.

Attachment of the seat to the fiberglass panel is interesting in itself. Rather than hinges, Vetter uses a material called Velcro in narrow strips applied to both fiberglass panel and the bottom of the seat. Velcro is a fabric that comes in two accompanying forms, polyester hooks and polyester pile. When the two opposing forms of Velcro are pressed together, the hooks interlock with the pile and the seat is firmly attached. The Velcro lock is released by yanking firmly on the seat, causing the polyester fabrics to deform temporarily.

Another consideration for Vetter was the marvelous sound of the BSA Three. This was one of its strong points. So he chose to emphasize this quality by exaggerating the "sound emitters," as he calls them, and grouping the three exhaust pipes into three racy looking mufflers on the right side of the machine.

The color for the fiberglass part of the machine is Camaro Hugger Red. It looks horrible splashed all over a Camaro, he says, but in the smaller amounts of space available on a motorcycle, it works quite successfully. The gold striping is aluminum/plastic Scotchlite applique, which, in addition to being a deep, elegant color, makes the machine safer because it is luminous and brightly reflects light from other vehicles at night.

As a totality, we are quite impressed with the Vetter BSA, because it seems not only to make the machine more modern, but more livable. Seating is quite comfortable, and it is obvious that Vetter has paid attention to rider position. He has definitely succeeded in coming up with a bike that invites you to climb on and take it for a ride.

He is already looking forward to designing other machines and is involved in Alcoa's Ventures In Design project. Alcoa picks only four designers a year for this project, gives them the materials they need and tells them to "make something nice out of aluminum."

Prototype, pipedream, experimental styling concept, or what have you, the ultimate adoption of the Vetter design by BSA now depends upon the reaction it gets from the public and the reception from the people back home in Birmingham. That it was ever commissioned at all is one of the most remarkable things to happen in the history of English motorcycle manufacturing. (O)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1970 -

Features

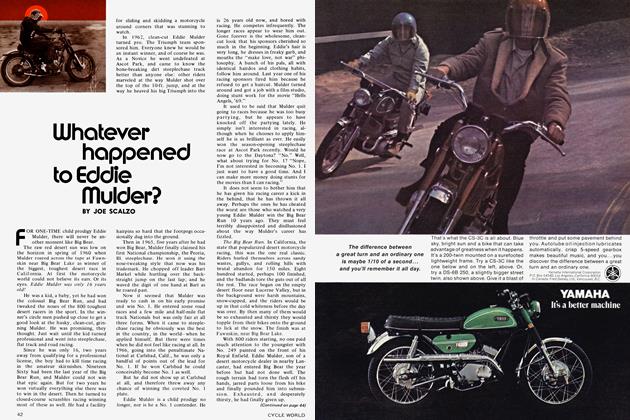

FeaturesWhatever Happened To Eddie Mulder?

September 1970 By Joe Scalzo -

Competition

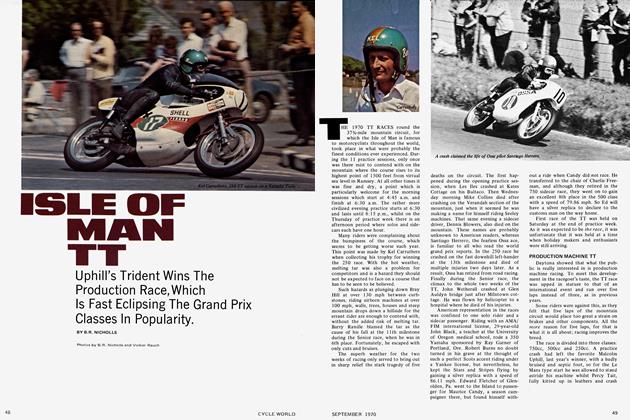

CompetitionIsle of Man Tt

September 1970 By B.R. Nicholls