THE DRAGSTER: HOW AND WHY

The Rationale Behind One Of The World's Fastest Drag Bikes. A discussion Of Riding Technique. And The Reason Why Boris Murray Thinks He Can Beat Those Eastern Cats.

DAN HUNT

IF YOU HAPPEN to meander off the street on a Saturday night, drawn by the noise of your local drag strip, you’ll find a confusing, almost repelling, scene. But, perhaps you wanted to find out how fast your bike would go.

Now you’re caught up in the bedlam. You pay the entry fees and after standing around at the start, inconspicuously, you hope, you take your machine towards the starting lineup, hoping to thread your way in between an endless procession of cars which make horrible noises and threaten to eat both you and your beloved motorcycle alive.

Staring in awe as flames belch from the stacks of a supercharged fuel car being started by spinning the back wheels on an electrically driven steel roller, you don’t see the starter waving at you, until he comes over and taps you brusquely on the shoulder.

You’re on! He’s beckoning you to the line.

You paddle your machine, running in neutral, trying to follow his sign language the best you can. The front wheel of the bike has barely reached the line and the starter taps your helmet to get your attention. He’s pointing at that crazy set of lights suspended between the two running lanes: the Chrondek “Christmas Tree.”

You’ve watched it work before. Five amber lights will flash in rhythmic sequence down the tree until the green is reached—the signal to go. If you go early, you will “red light.” Which means you would be disqualified if you were match-racing somebody in the other lane. If you go late, you may lose.

But first you have to “stage.”

As you inch forward a small yellow “pre-stage” light atop the Christmas Tree comes on. A hair farther and the second “stage” light winks. Oops, too far. It went out. The starter is impatient, nervously looking back at the fuel car which has finally erupted into steady life. He yanks you physically backwards until both lights are lit again. A second street bike has staged quickly in the other lane. Squeeze clutch—in gear. Suddenly, the Christmas Tree has begun its amber blinking dive, and that other bike is off right on the green. By itself, certainly not because of you, your bike also leaves the line in a noisy, swimming slow motion. It takes forever to pass through the quarter-mile traps. And, once past and pulling off into the return road, you realize you have been beaten. Dumbly.

You may or may not care. Picking up your timing slip at the tower and finding out how fast your model goes may be satisfying enough. Out to the street, to other diversions.

Or you may come back. Like Boris Murray. He started this way. He lost. And he kept coming back. Now he is one of the select few in this country who have piloted a tire-smoking, onegear motorcycle through the traps at more than 165 mph.

His 9.25-sec. elapsed time from start to finish also makes him one of the quickest. But not the quickest. That honor belongs to a machine owned by Sonny Routt and ridden by Larry Welsh; it holds the record at 9.1 0 sec.

And, as any drag buff will tell you, it is elapsed time that wins a match race. It doesn’t much matter how fast you are going when you get there, if you don’t get there before the other guy does.

Boris Murray would like a crack at “Routt & Co.” He thinks they have gotten too much press. Please understand that he’s not putting them down. It’s merely that Routt & Co. happen to be in the right place right now. So they get the breaks and the benefit of heated competition.

The East, and to some extent the Midwest, is where motorcycle drag racing is happening. It used to be in the West, but it has faded from lack of organization and interest. And because the bikes have been crowded off the drag strips by all those weird cars.

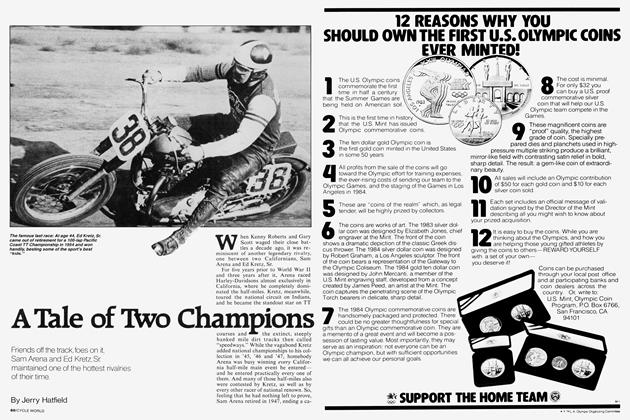

As you might have guessed, Boris Murray —a lanky (6 feet 4), gentle, 175-lb. construction worker—is a Westerner. Routt & Co. is in the East. It would be just dandy to stage a match race between the two, for each is the cream of his region.

Murray’s best competition in his own area is Joe Smith, who rides a 102-cid Harley fueler, and won the Irwindale National this Spring. Smith has run a 9.34-164.27.

In the East, competition is thicker for Routt’s double-engined Triumph, which has had to face off against the Sportsters of Bob Barker (9.30), Nick Palmerone (9.30), Guy Learning (9.26), Jim De Salvo (9.23), and the Sportster belonging to Routt’s own rider, Larry Welsh (9.28). Competing against both East and West, Wisconsin rider Leo Payne, who successfully deflated a few California egos a few years back, is always a threat on his 9.30-sec. Harley fueler.

Murray, who can console himself for the time being with the best documented top speed through the traps, has what he feels are good reasons for wanting to run against Routt. For one thing, he’s positive he can beat him.

He thinks the Eastern dragstrips are quicker. “None of those guys who have come out here do as well as they do at home. I’ve heard that the timing lights are mounted differently there.”

Further, he feels that his machine, a two-engine Triumph with Chantland 750-cc barrels similar to Routt’s is faster than Routt’s, because it is lighter (304 lb. to Routt’s 330 lb.) and may handle better, yielding consistent runs.

Unfortunately, Boris may have to wait some time before he can prove his point. The problem is that big time motorcycle drag racing is not very big time at all—not if you compare it to its counterpart in the automobile world. For example, there is no established national championship drag circuit for motorcycles, and thus no ready means to provide elimination match races of truly national significance. Except for big money at a select few meetings, the purses paid for Top Fuel Eliminator at regular regional events are pitiful, and consistent support from the trade in the form of parts and contingency money is rare.

Murray is no different than most of the big guns. He finances practically all of his racing operations by working a steady job. Some day he may travel East to do battle with Routt and the others, but he’ll pay the tab himself. Fortunately, his construction job allows him a certain amount of time off, and he could conceivably go East if he can “save up enough marbles,” as he puts it.

If you take a typical weekend, you can see what Boris is up against. The average purse for Top Fuel at a local meeting is $75. At the all-bike Irwindale National, where Murray broke a chain, he could have won more than $1000, but that sort of event is a rarity in the West.

So, assuming that he wins his $75 each week, he has to pay the costs of running. They are devastating for a fuel bike.

“By the time I pay my way through the gates and make three runs, I’ve already spent $60 or $65. That includes my entry fees and admission for my family. Imagine, I’m part of the show and I’ve got to pay admission! I get only four runs out of my rear tire (a special 4-in. Avon drag slick), and it costs about $50. The fuel costs $7.50 a gallon. Then there’s plugs and parts. Nobody gives me all that stuff.”

These costs, of course, do not even take into account the expense of building his rig, or the normal wear and tear on it in the course of a season. And wear and tear on a fuel bike can hardly be considered normal. Not when two Triumph Bonneville Twins, designed to perform reliably on the street with an output of 55 bhp, are suddenly pushed with the aid of big bore barrels and an explosive nitromethane fuel mix to a combined output of more than 225 bhp.

Under such conditions, Murray’s machine must be considered a paragon of reliability. For example, he may bother to overhaul the valve gear only once every three months.

Part of this reliability stems from the inherent strength of the big Triumph engines. What is amazing is how “stock” these engines are. Most of the lower end parts are standard, including the 1969 Bonneville crankcases, rods and roller bearings. The heads receive somewhat more attention; the intake ports are cleaned up and enlarged to accept 1 5/8 valves, but the exhaust valves are standard size. Both sets of valves are closed by Triumph five-coil racing springs, racked to matching poundage. As fuelers gobble great amounts of nitromethane, Murray uses remote float Amal TT carburetors with big fuel lines.

In the interest of power train reliability, the driveline—i.e., the centers of the rear engine output shaft, the clutch drive and the rear axle—follow an absolutely straight line. This measure prevents any off-center pressure on the transmission. The necessity for such a layout became quite evident to Murray with his previous machine, on which the clutch center was below the drive line: the tremendous self-centering torque forces succeeded in pulling the transmission up and out of the frame!

Most of the double’s go-power comes from the fuel itself, a mixture of 90 percent nitromethane, which creates its own extra supply of oxygen as it burns and an igniter called propylene oxide. On hot days, to prevent detonation, Boris may add some benzol to the mix. A Harman & Collins camshaft of moderately high lift (No. 76, .359 in.) times the valves. However, the specially cast Chantland big bore barrels, which increase displacement of each engine from 650cc to 750cc for a total of 1500cc or 90 cu. in., are most responsible for getting the machine into the 160s. Murray’s machine is thus giving away about 10 to 13 cubic inches to the Harleys which run in the same class, but his double Triumph is turning higher rpm. It is this rpm factor which gives the Triumph combination its top speed superiority, Murray feels.

“A good open class Harley fueler can get under a 9.50-sec. elapsed time, yet top out at only 150 or 155 mph in the traps. I think the double Triumph is the way to go these days, because it really begins to come alive in the upper rev range. If I’m not careful, I’ve got enough power to spin the rear wheel even as I pass through the quarter mile.”

Design of the chassis and rolling gear is almost of greater importance to Murray than the power output of his engines. A badly designed frame can cause a phenomenon that fuel riders fear the most—speed wobble.

Wobble is terrifying. It usually happens during the fastest part of the run. The front wheel sets up a forceful oscillation that is carried back into the frame, which responds by amplifying the action and sending it back to the front wheel. If the rider is lucky, he has time to chicken out, to shut down until wobble mercifully stops. If the rider isn’t lucky enough, he and the machine part company.

The latter circumstance has led to rather amusing instances, in retrospect, when riders have been timed through the traps at better than 140 mph, without their machines. It is not so amusing when the rider gets hurt. Speed wobble is the reason, for example, why Sonny Routt is no longer riding for Sonny Routt.

And the threat of speed wobble will make a 10-sec. rider out of many a man on a 9-sec. machine.

“That’s why I think it is important to build a good handling machine,” says Murray. “Joe Smith has handling problems, and you can see it when he goes to the starting line. He’s white as a sheet. Unless you have confidence in your machine, you can’t be consistent, and consistency is what gets you Top Eliminator.”

Murray’s conception of proper handling begins with the wheelbase. For a machine putting out the horsepower necessary to win in his class, he feels that 63 to 64 in. is appropriate. Make it any shorter and the bike wants to swap ends, or it transfers too much weight to the back end and the bike wheelies. If the wheelbase is too long, you lose traction and the bike suffers from a slow, snaky motion all the way through the quarter mile. As the fueler gains motion, Murray lets the force of acceleration lever him gently backwards in the seat towards the rear fender. In the first eighth mile, this movement may amount to only 6 in. In the last eighth mile, he is concentrating on keeping his body tucked in and out of the wind. But his bike is so powerful that he must keep track of his weight distribution during the last moments of the run also. The force of acceleration actually increases as the fueler gets running faster than 140 mph a short distance before the 1/4-mile traps. It is a strange feeling, quite contrary to that expected from a motorcycle of more moderate power output.

Rake and trail are also important. Murray’s dragster forks have a 36-degree rake from the vertical and 4.5 in. trail. His bike runs straight as an arrow from start to finish, and he has no fear of wobble. His West Coast rival, Smith, has wobbling problems with his front end (39-degree rake, trail unknown).

Rigidity is another prime requisite in Murray’s scheme of things. That is why he has fashioned his frame of straight 4130 chrome-moly steel tubing with no “exotic bends.”

Here’s a quick rundown on some of the dimensions and features of Murray’s machine:

Wheelbase: 63.0 in.

Weight: 304 lb.

Weight distribution: 43.5 percent front/ 56.5 percent rear.

Fuel capacity: 2.5 qt.

Oil capacity: 2.0 qt.

Handlebar height: 33.0 in.

Seat height: 24.0 in.

Footpeg height: 4.0 in.

Ground clearance: 4.0 in.

Front suspension: Triumph Terrier telescopic forks.

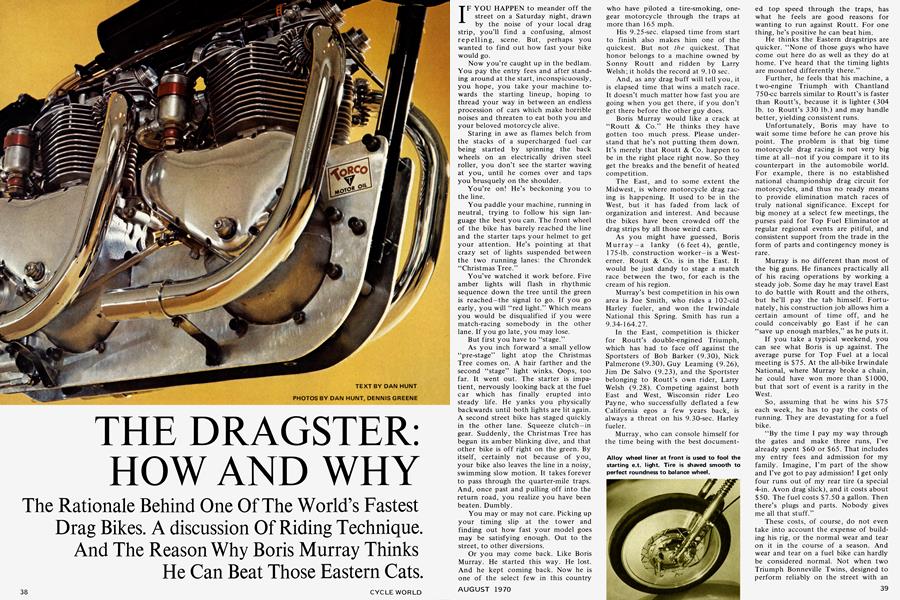

Front rim and tire: Borrani WMO, Pirelli ribbed (shaved smooth) 2.50-18.

Front brake: Airhart 11-in. disc.

Clutch: 11-plate Harley-Davidson Sport-

ster.

Engine to engine chain: No. 40 Primary drive: triplex Sportster chain.

Final drive: single-row 3/8 by 5/8 in.

prestretched Diamond chain.

Gear ratio, overall: 3.69:1.

If you visualize this intangible set of dimensions, you will come to the conclusion that Boris Murray goes racing on a very strange machine by normal motorcycling standards. The bike is long and low; the rider’s body is pitched forward over (and barely a few inches from) those frighteningly powerful engines and the tube-shaped tank full of noxious fuel. After the machine is under way, the rider’s feet will move back to ride on pegs suspended near the rigidly mounted rear axle. He will be almost prone. The position is suspiciously suicidal, much like that in the camera pod of a fighter plane. But the ride is short, as is the discomfort. So everything must be done to cheat the wind, yet allow correct weight transfer to the rear wheels for optimum traction.

When Boris Murray goes to the starting line, he brings with him the technique gained from years of straight-line competition. He and his compatriots probably take their skill for granted. But a few points of his technique are well worth noting, if you plan to be a fuel rider, or even if you only plan to run e.t. brackets with your street bike.

The first thing he does after his engine is operating properly is a “burnout.” It sounds and looks hairy, but really isn’t. It involves spinning the rear tire for a few seconds while the drag bike is stationary, with the front wheel braced against a car bumper or other relatively immovable object. An old hand will merely make an aborted 20-foot drag start. Whoosh! The tire smokes and heats up. Reason for the burn-out is that a hot tire has a much better coefficient of friction than a cold one. The heat makes the rubber tackier and more supple.

By burning out the tire, as much as a half-second improvement in elapsed time is gained just before staging, says Murray. Starting cold, it would take 200 ft. of tire spin out of the gate to get it sticking properly. The ultimate combination for traction occurs when the burn-out has been performed and the surface of the dragstrip itself is hot. While the technique is most useful on a special compound tire such as the Avon 4.00-18 drag slick, which presents most of its face to the ground, it may prove useful with some street tire compounds, or on a big, cammy street bike that requires the rider to spin the back wheel off the starting line.

Now to the staging area. Even before he gets the green light, Murray has prepared for a timing light quirk with a device, mostly seen in the East and Midwest until now, that will gain him several hundredths of a second without lifting a finger. Notice that wide alloy sheet that runs around the inside of his front rim? It takes advantage of the fact that the light beam used to actuate the electronic elapsed time clock does not start the clock running until the beam has both been broken and then reopened as the front wheel passes by. If only a 3or 4-inch section of the normal tire-spoked rim combination cuts the beam as it rolls forward, the reopening occurs relatively quickly. But if that beam is kept closed for moments longer by the metal panel inside the rim, the reopening of the beam, and resulting actuation of the e.t. clock, is delayed. The bike has a chance to get rolling a fraction of a foot farther and gain traction. And a nominal lowering of elapsed time results.

A further advantage of the rim liner is that the resulting delay in reopening of the timing light beam will help prevent the rider from “red-lighting” if he anticipates the green light too much.

When Murray is staged, he has his eye on the Christmas Tree, waiting for those amber lights to begin their sequence. When the ambers are blinking, 1-2-3-4-5, he is watching the Christmas Tree. But he does not wait to see the green “go” light before starting. When he sees the last amber, he looks straight ahead and goes. This technique rarely causes him to leave early, or “red light.”

“The time between that last amber and the green is very short,” he says. “I can’t bring myself to look over at the green. That is the most important time to be looking straight ahead, with your head and body and the machine straight up. You want to come out straight. Getting sideways loses time.”

Other riders solve the problem differently, by counting in rhythm to themselves as the amber lights flash. But the object is the same. To get off exactly with the green, and have full attention on the business at hand, which is to go straight forward, as quick as you can.

Having all that horsepower on tap means that Murray does not have to be overly selective about his rpm when he engages the clutch. It is more important that the bike doesn’t “bog,” or catch too much traction, causing the engine to drop off the power curve. The machine has only one gear, with a 3.69:1 overall ratio, calculated to rocket him through the traps at more than 165 mph with the engines turning at about 8000 rpm. That rear tire is his transmission and it will be spinning and smoking against the pavement most of the way down the strip.

Murray doesn’t even bother to change gearing to match the strip or traction conditions prevailing on a certain day. He could gear slightly lower, he says, and thus have an easier time getting consistently low elapsed times, but he wouldn’t get that impressive top speed. “I want that speed partly for prestige,” he admits.

So his main problem is correct application of body english—to deliver just the right amount of weight to the rear tire.

“No matter how I start, the bike will turn about 165 mph. But the real skill is getting that elapsed time down. You have to work to get good e.t.”

Should he jerk his body backward too brusquely at the start, the front wheel will jump in the air. But should he merely sit still on the machine, the rear tire may not get enough of a bite and the bike will just sit there, smoking the tire. Both these errors cost valuable time.

Directional control is important at the start, too, which is why Murray snaps his feet up to the pegs immediately after he drops the clutch. “I feel I have more control of the bike if my feet are on the pegs. My balance is better. And I have better control of body english. I can’t understand these guys who leave their feet down as outriggers. They look awfully amateurish and they don’t get off as straight as they should.”

(Continued on page 78)

Continued from page 41

At both the early and late parts of the run, Murray is able to get a “reading” of his weight distribution from the behavior of his front end. Optimum traction is indicated when the steering is light, and seems to have but an airy contact with the ground. If the steering seems to be too firm, too much weight is forward, and he gently moves backward on the seat to improve traction. If the front end seems to float, or swim, and the steering seems to have absolutely no connection with the ground, weight transfer to the rear wheel is excessive and possibly dangerous.

When he first made the changes to his machine that boosted his speed into the 160s, front end float became quite a problem. The air pressure against rider and machine at that speed was causing the front end to get light, and Murray had to overcompensate to keep the front end down as he passed through the traps, thus costing him traction.

He solved the problem by mounting a tiny metal plate, angled down at 15 degrees, on his triple clamp. It is only a few inches wide, but with the great air pressure at 165 mph, it produces a substantial downward force on the front end of the machine. Now he may safely transfer more weight to the back of the machine during the last part of the run.

Murray is one of the few fuel bike riders to use a front brake on his machine. Usually a drag bike has only a rear brake. A front brake means extra weight, and weight reduces acceleration.

But Murray had a bad experience once. His rear brake broke, and he was going so fast that he ran out of room to slow the bike down. He had to throw the bike away.

Since his machine weighs less than most of his competition, he decided that the 10-lb. weight penalty of a front brake was a worthwhile investment.

He knows for sure that his bike can be stopped. He knows that his bike will handle straight and true. The dimensions are proper, and the frame is rigid. He doesn’t have to think about the possibility of speed wobble or snaky handling.

In short, he has confidence when he goes to the starting line. And confidence is half of winning.

“If I ever got into a high-speed wobble,” he says, “I think I’d hang it up. It would scare me to the point where I’d say the hell with racing.”

At which point, the East Coast boys would breathe a lot easier.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

August 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

August 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

August 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesThe Princess & the Peasant

August 1970 By Cecil P. Mack -

Competition

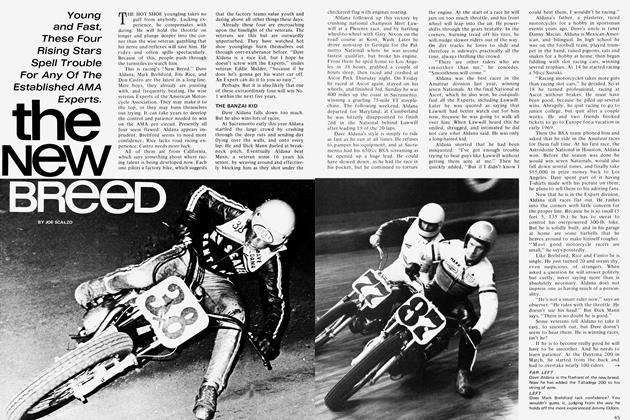

CompetitionThe New Breed

August 1970 By Joe Scalzo