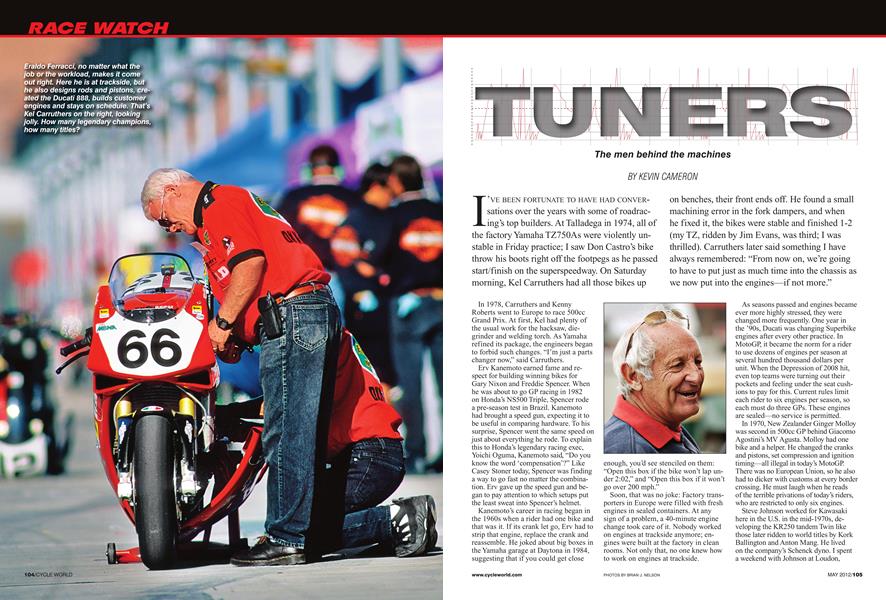

RACE WATCH

TUNERS

The men behind the machines

KEVIN CAMERON

I'VE BEEN FORTUNATE TO HAVE HAD CONVERsations over the years with some of roadracing’s top builders. At Talladega in 1974, all of the factory Yamaha TZ750As were violently unstable in Friday practice; I saw Don Castro’s bike throw his boots right off the footpegs as he passed start/finish on the superspeedway. On Saturday morning, Kel Carruthers had all those bikes up on benches, their front ends off. He found a small machining error in the fork dampers, and when he fixed it, the bikes were stable and finished 1 -2 (my TZ, ridden by Jim Evans, was third; I was thrilled). Carruthers later said something I have always remembered: “From now on, we’re going to have to put just as much time into the chassis as we now put into the engines—if not more.”

In 1978, Carruthers and Kenny Roberts went to Europe to race 500cc Grand Prix. At first, Kel had plenty of the usual work for the hacksaw, diegrinder and welding torch. As Yamaha refined its package, the engineers began to forbid such changes. “I’m just a parts changer now,” said Carruthers.

Erv Kanemoto earned fame and respect for building winning bikes for Gary Nixon and Freddie Spencer. When he was about to go GP racing in 1982 on Honda’s NS500 Triple, Spencer rode a pre-season test in Brazil. Kanemoto had brought a speed gun, expecting it to be useful in comparing hardware. To his surprise, Spencer went the same speed on just about everything he rode. To explain this to Honda’s legendary racing exec, Yoichi Oguma, Kanemoto said, “Do you know the word ‘compensation’?” Like Casey Stoner today, Spencer was finding a way to go fast no matter the combination. Erv gave up the speed gun and began to pay attention to which setups put the least sweat into Spencer’s helmet.

Kanemoto’s career in racing began in the 1960s when a rider had one bike and that was it. If its crank let go, Erv had to strip that engine, replace the crank and reassemble. He joked about big boxes in the Yamaha garage at Daytona in 1984, suggesting that if you could get close enough, you’d see stenciled on them: “Open this box if the bike won’t lap under 2:02,” and “Open this box if it won’t go over 200 mph.”

Soon, that was no joke: Factory transporters in Europe were filled with fresh engines in sealed containers. At any sign of a problem, a 40-minute engine change took care of it. Nobody worked on engines at trackside anymore; engines were built at the factory in clean rooms. Not only that, no one knew how to work on engines at trackside.

As seasons passed and engines became ever more highly stressed, they were changed more frequently. One year in the ’90s, Ducati was changing Superbike engines after every other practice. In MotoGP, it became the norm for a rider to use dozens of engines per season at several hundred thousand dollars per unit. When the Depression of 2008 hit, even top teams were turning out their pockets and feeling under the seat cushions to pay for this. Current rules limit each rider to six engines per season, so each must do three GPs. These engines are sealed—no service is permitted.

In 1970, New Zealander Ginger Molloy was second in 500cc GP behind Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta. Molloy had one bike and a helper. He changed the cranks and pistons, set compression and ignition timing—all illegal in today’s MotoGP.

There was no European Union, so he also had to dicker with customs at every border crossing. He must laugh when he reads of the terrible privations of today’s riders, who are restricted to only six engines.

Steve Johnson worked for Kawasaki here in the U.S. in the mid-1970s, developing the KR250 tandem Twin like those later ridden to world titles by Kork Ballington and Anton Mang. He lived on the company’s Schenck dyno. I spent a weekend with Johnson at Loudon, New Hampshire, where Ron Pierce rode Steve's KR to a promising win against Yamahas. Tn 1981, Johnson was crew chief on an Eddie Lawson European foray into 250cc GE Three years later~ Lawson would be 500cc world champion.

When Yamaha brought out its FZR75O, Johnson was on another dyno at an aftermarket company, develop ing pipes and modifications. His work revealed that the five-valve cylinder head imposed hard compromises. If you raised the compression to make the bike accelerate, the broad combustion cham bers became so thin that combustion slowed down, chopping revs and torque off the top. To get top-end, you had to open up the chamber, which meant giv ing up the acceleration that high com pression brings. This was "the Formula One syndrome" that affected all the Japanese brands from the later 1980s to mid1990s.

During the winter of 1992, the fivevalve Vance & Hines Yamaha AMA Superbikes took a big step forward in performance. Crew chief Jim Leonard had pushed through a radical project: to relo cate the engine's five valves in a tighter cluster, nearer the center of the chamber. The aim was to reduce intake-valve mask ing by the nearby cylinder wall.

I thought about the problems of re angling everything so that the seats and heads of the valves were relocated, but the tappets were still where they had to be-under the cams. This was a huge project. When I asked how it was done, Leonard said rather casually, "They have some Mazaks out there in the shop." (Mazak is a major Japanese brand of CNC machining center.)

Mazaks weren't the only V&H asset "out there in the shop." Byron Hines may say little, but he accomplishes much.

In our brave new world of engines as no-touch`em "black boxes," the intimate business of changing the valve angle of even a two-valve engine is so esoteric that most have never heard of it. To change the positions of 20 valves and then win national races with the result is off the charts. Hats off to Leonard and Hines.

Tom Houseworth has now been crew chief with Ben Spies through three AMA Superbike championships, a World Superbike title and two years in MotoGP. Houseworth says his major task in that WSBK year was keeping the Italian mechanics from changing things on the bike.

Almost 20 years ago, Houseworth was on Yamaha's AMA Superbike team.

"We're all sitting in a big meeting in Japan," he said. "They tell us, `Please give us your suggestions for how we can improve performance.'

"I raised my hand, and they called on me. I asked, `How about a four-valve head?'

"After that, I had to eat lunch all by myself"

Tn 2003, Yamaha's crack problemsolver, engineer Masao Furusawa, was asked to make a winner of that compa ny's troubled 990cc YZR-M1 MotoGP bike. Knowing management might not like what he suspected was necessary, Furusawa put the choice to newly hired rider Valentino Rossi. Four bikes were built for Rossi to test: 1) standard Ml with traditional flat crankshaft and Yamaha's "signature" five-valve cyl inder head; 2) flat crank and new four valve head; 3) new low-inertia-torque "crossplane" crank and five-valve head; 4) crossplane crank and four-valve head.

Rossi went fastest on #4, which he used in 2004 to win Yamaha's first MotoGP championship. He won again in 2005, 2008 and 2009. Today, Yamaha's top production sportbike, the 1000cc YZF-R1, has also become a #4.

Veteran of years of high-level AMA Superbike and Supersport preparation and trackside tuning, Vie Fasola has the natural dignity of a man with the confi dence of his convictions. When as AMA tech inspector, I walked into the Suzuki Cup tech garage after all the racing was over, Fasola looked down at me (he is amazingly tall) and said, "What are you even doing here, man? You know as well as I do that all these guys [he indicated the other crew chiefs and mechanics in the roomi spend 100 percent of their time with these bikes, thinking about them, working on them, looking for ways to make them quicker. And here you come. Being tech inspector is just a little part of your year, and you're supposed to be able to figure out all the tricks. No way!"

What could I say? He was right. So, I said, "I agree. I'm just here to give some assurance to the man in fourth place that the three guys ahead of him actually beat him. Maybe it's just going through the motions, but it's necessary."

Peter Doyle has been crew chief with Yoshimura Suzuki since 2001. He is the son of Neville Doyle, the respected Kawasaki two-stroke specialist. Doyle sees what bikes do. At his first test with the team, at Willow Springs in California, he saw that Mat Mladin's GSX-R750 was pushing-not holding line as it acceler ated off corners. With spare seat padding and duct tape, he moved Mladin forward on the bike, increasing the load on the front tire just enough to keep it steering. Next practice, Mladin was more than a half-second a lap quicker. If you ever wondered why gas tanks are so short to day, there's your answer.

Ammar Bazzaz, who came to Yoshi mura from academia as an instrumen tation specialist, spoke of the team's success (10 Superbike titles in 11 years): "Continuity," he said. "That is the key."

Racing was Yoshimura's business, so team personnel didn't change and always looked like they were having a good time. They weren't the all-too-common "telephone team," hired in a January "policy panic" and expected to win in March with a new model and no parts.

Al Ludington worked many years as crew chief with Miguel Duhamel at Honda and then went to Kawasaki briefly with Eric Bostrom. At that time, he said, "Kawasaki has a creative degree of desperation. At Honda, if we asked for a shock-link anchor change, there'd have to be meetings, and it'd take four months. At Kawasaki, they get a Sawzall, cut out the mount, weld the new one in the new location and start testing."

Just like Carruthers 30 years ago, saw ing the steering head out of Roberts' YZR500 and then welding it back in at a new angle. Do whatever it takes-now.

Ludington talked about such modifi cations making a chassis hook up better off corners so it would get to the next turn quicker. Soon, there'd be paddock talk that they had "a cheater motor." In tech, the AMA would want the engine, so they'd pull it.

"Can I just roll the chassis away?" Ludington would ask.

"Sure, sure," was the reply from har ned personnel (all those engines to measure and nothing to eat after a day in the hot sun).

"And so I'd roll away the really inter esting stuff."

Today, Ludington is AMA Pro Racing's Technical Director.

When Eraldo Ferracci came to this country, he saw that drag racing was a popular motorcycle sport, so he built drag bikes and was successful. He got tired of it. "I think I want to see the engines run a little longer than that," he said.

Ferracci moved into roadracing and quickly made the reputation of build ing reliable bikes that won races. He became a trusted "arm" of Ducati, es sentially creating the 955 by solving outstanding problems of the previous machine. He is an engineer without a degree. When I need to understand what's happening, I look for Ferracci.

Gary Mathers was Kawasaki's rac ing manager in the years when Rob Muzzy (aka "Mr. Superbike") built the bikes that made Eddie Lawson AMA Superbike champion. When Kawasaki had its usual "new policy" and switched off racing, Mathers and Muzzy went to Honda and continued as before. Mathers' method was to find the right people for the various jobs and let them get on with it. He greatly respected practical trackside experience.

Asked about the role of engineers in his department, Mathers replied, "Engineers? We don't let those guys any closer to our bikes than the loading dock. Here's a question: The hay is cut, the baler's broken and rain is coming. If the hay gets wet, it's ruined. Who do you get to fix the baler? Engineers? They form a study group and in six months they issue a report. No, when the baler has to be fixed right now, you get a farmer."

Mathers once explained that he breaks each team's performance on any given weekend into bike, rider and support. Each category has "five or six subsec tions, each rated on a one-to-lO basis. The team that wins, if you do it objectively, al ways has the highest cumulative score. Of course, it's hard to rate your own outfit."

Muzzy separated from Kawasaki at the end of 1999 after being involved in AMA Superbike since 1981. He looked into drag racing. At the first event he attended, he was deluged with orders for pipes and other accessories, something that had never happened at the roadraces.

"I'd always thought roadracing was the way to reach motorcyclists," he said. "I was amazed. Once we began to advertise stuff we were making for drag racing, it took us 18 months to get out from under the backlog of orders we got."

When I interviewed Muzzy in 1982 at Kawasaki's race shop, he made a funda mental point: "Never do more than 80 per cent of what you can think of doing in any one area. Any more than that is taking time from something else that needs it more."

Muzzy had a good poker face, but experienced watchers knew that if he strolled the pits Saturday afternoon eat ing ice cream, other teams would be fighting for second on Sunday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAmusement Parks And the Leisure Gap

May 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

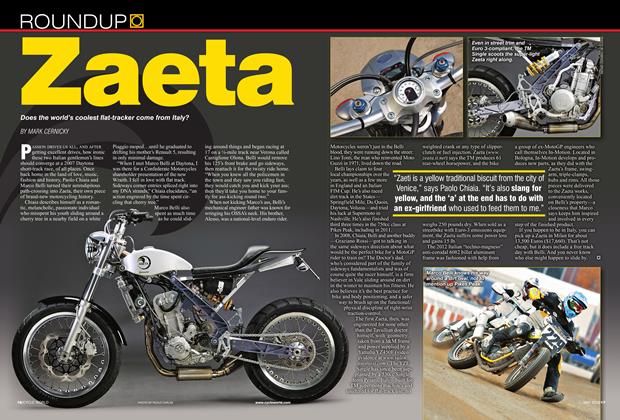

Roundup

RoundupZaeta

May 2012 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

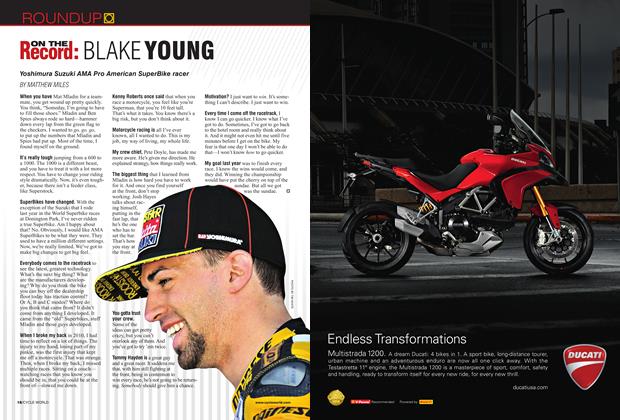

RoundupOn the Record: Blake Young

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRide Faster. Ride Safer.

May 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago May 1987

May 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupIs the Ducati For Everyone?

May 2012