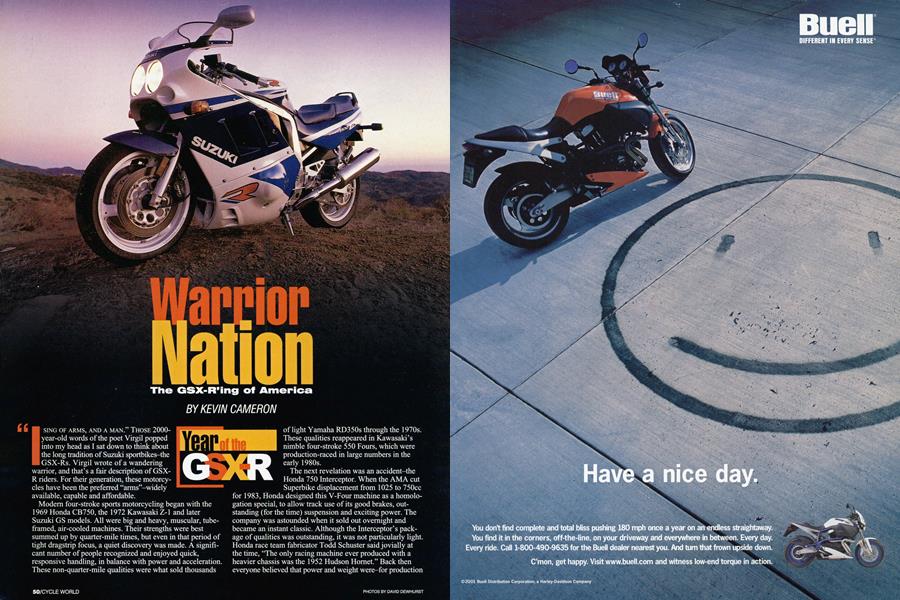

Warrior Nation

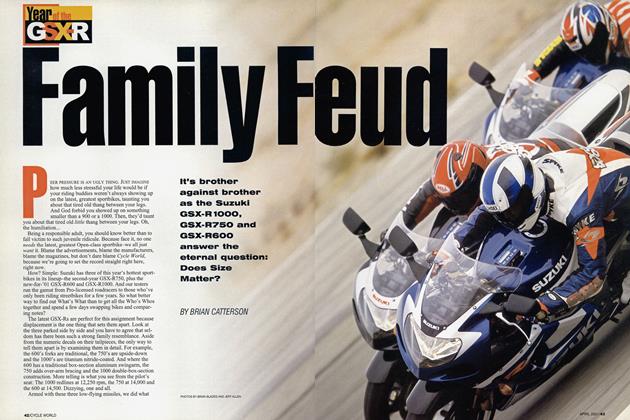

Year of the GSX-R

The GSX-R'ing of America

KEVIN CAMERON

"I SING OF ARMS, AND A MAN." THOSE 2000-year-old words of the poet Virgil popped into my head as I sat down to think about the long tradition of Suzuki sportbikes—the GSX-Rs. Virgil wrote of a wandering warrior, and that's a fair description of GSX-R riders. For their generation, these motorcycles have been the preferred "arms"—widely available, capable and affordable.

Modem four-stroke sports motorcycling began with the 1969 Honda CB750, the 1972 Kawasaki Z1 and later Suzuki GS models. All were big and heavy, muscular, tube framed, air-cooled machines. Their strengths were best summed up by quarter-mile times, but even in that period of tight dragstrip focus, a quiet discovery was made. A signifi cant number of people recognized and enjoyed quick, responsive handling, in balance with power and acceleration. These non-quarter-mile qualities were what sold thousands of light Yamaha RD35Os through the 1970s. These qualities reappeared in Kawasaki's nimble four-stroke 550 Fours, which were production-raced in large numbers in the early 1980s.

The next revelation was an accident-the Honda 750 Interceptor. When the AMA cut Superbike displacement from 1025 to 750cc for 1983, Honda designed this V-Four machine as a homolo gation special, to allow track use of its good brakes, out standing (for the time) suspension and exciting power. The company was astounded when it sold out overnight and became an instant classic. Although the Interceptor's pack age of qualities was outstanding, it was not particularly light. Honda race team fabricator Todd Schuster said jovially at the time, "The only racing machine ever produced with a heavier chassis was the 1952 Hudson Hornet." Back then everyone believed that power and weight were-for production motorcycles-inseparable by reason of cost. Lightness was too expensive for the street rider. Locomotive sportbikes were accepted with 200-pound engines in 300-pound chassis.

Acceleration equals thrust, divided by weight, but big motorcycles of the 1970s had been built as if more thrust was the only path to higher acceleration. Suzuki decided to apply to this problem what it had learned in GP racing. Not only could a given engine accelerate a lighter bike faster, but its rider could toss it into and out of comers more easily, and finish the day less fatigued. Light weight was good. Suzuki would find a way around the high cost of lightness. A simplified transverse inline four-cylinder engine in a GP-style square-tube aluminum chassis, with similarly light cycle parts, resulted in a new kind of sportbike. Its major feature was not locomotive horsepower, but rather a total weight 100 pounds lighter than comparable machines. The power of the new oil-cooled engine moved this lightweight easily, setting new standards for all-around performance.

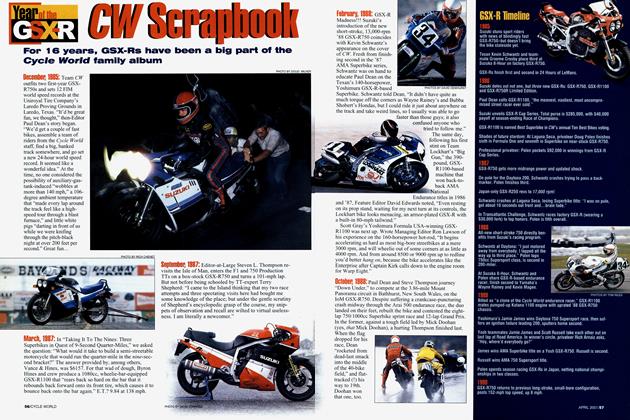

Better yet, the GSX-R was not a one-time signal flag, run up the halyard to get attention and then pulled down just as quickly. It was the beginning of an enduring tradition of 600, 750 and Open-class GSX-Rs that extends to this day.

When Yamaha first ran its five-valve FZ750s at Daytona, race team manager Kenny Clark predicted that, “This engine will become the small-block Chevy of motorcycling.” He was right about the concept, but it would be the Suzuki GSX-R that assumed that role.

Beginning with its introduction, the GSX-R in all its forms has been the most substantial basis for sports production racing at local and national level. These have been motorcycles that responded ideally to the Supersport racing concept. Add high-grip tires, with matching springing and damping, remove unnecessary parts like tumsignals, stands and lights, and you have affordable, maintainable, competitive machines. So strong has this effect been that the traditional trainingground of future champions, the 250 GP class, has been displaced by production-based 600 and 750cc Supersport. Suzuki’s U.S. importer has for many years supported privateer racing through contingency awards and the Suzuki Cup Series.

On the street, GSX-Rs are affectionately referred to as “Gixxers,” and are the factory hot-rod most often chosen by sport riders. Alternatives exist, and there is always the seesaw of whose specs are tops this week, but Suzuki is always a contender, not a summer soldier.

The long GSX-R tradi tion and substantial pro duction numbers have made these bikes attrac tive to the aftermarket, so cams, pistons, carburetors and other hi-po parts are plentiftil.

Just as Corvette is always front-engined with V-Eight power, has a fiberglass body and is the essential American sports car, so the GSX-R remains the classic modem embodiment of the sportbike, powered by an east-west inline-Four in a concept traceable back to the originating Rondine/Gilera of the 1930s. It works, people know what it is, and it seems unchangeable.

For some factories in Superbike racing, the 750 model is a pure homologation special, seen only in track paddocks and private collections. By contrast, not only are Suzuki GSX-Rs actual mass-produced production motorcycles, seen everywhere, but this company banks on making money on their sale. This commercial aspect extends beyond the actual 600, 750 and Open GSX-Rs themselves, for the company has employed less sharply tuned versions of their engines in other genres of machine. Shared parts and modular construction are sensible economies, and a close look at any GSX-R reveals that it is designed for economical production. This strategy has allowed these machines to be sold at prices that attract lots of buyers.

Another important basis for the popularity of these machines is that they deliver performance without resort to technological fuss. Their engines are compact but uncomplicated. The aluminum chassis get the job done without excessive cleverness. These motorcycles are basic, simple and well-executed. Periodic redesigns have kept performance high, but remained faithful to the enduring personality of the original.

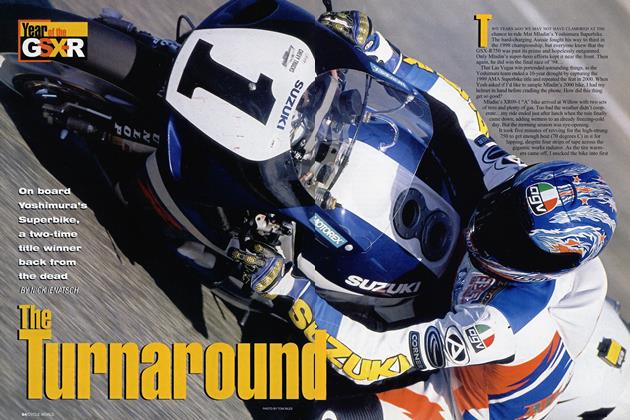

There are other ways to build sportbikes: V-Twins, for example, or with the cylinders in alternative configurations. No one plan has given a monopoly of performance. Nature rewards simplicity, so it makes sense to build the simplest motorcycle that offers the necessary performance. The resulting lower price offers ownership to the widest population of riders. It works in racing as well. This year’s defending AMA Superbike roadracing champion, Mat Mladin, achieved this distinction on a Yoshimura/Suzuki GSX-R750.

There have been ups and downs in the continuing development of these bikes. The 1988 750’s piston stroke was too short for best combustion, so the following year the longer stroke was reinstituted. Weight growth is just as hard to avoid for machine as for rider, and at least twice redesigns have been necessary to chop the GSX-R back to its original lean concept. Suzuki Superbike racing development lagged for a few years in the early 1990s, relegating the Yoshimura Suzuki team to the back of the AMA paddock for a time. This made no apparent difference to the street popularity of GSX-Rs. Their reputation was secure, for the Gixxer had its place in the minds of riders.

At the races or anywhere else that sportbike riders gather, acres of GSXRs will be seen. Many of their riders travel in the official full sportbike outfit of one-piece leathers, top-line helmet and boots, and $ 150 gloves. Some are playing the racer-replica role to the hilt with top-rider lookalike helmet paint schemes, carbon canisters and even the gleam of titanium. A few have touched the ragged edges of the performance envelope, as shown by honorably scuffed leathers and tires, with pavement damage on footpegs and handlebar ends. Extreme sportbike riders like to say, “If you’re not sliding, you’re not riding.”

Another extreme contingent-seen at least as often-wears shorts, is helmetless where legal, shirtless and gloveless. On the feet are go-aheads, and the tach indicates 5000 revs under the power. 1 hope these riders survive their chronic undress, but despite that, they are having fun, too. For anyone but the strict utilitarians among us, choice of motorcycle includes a choice of style. Are all dual-sports ridden through bandit country to Dakar? Do all cruiser-jockeys wear their colors and chain-wallets into the corporate boardrooms where so many of them work? I don’t think so.

Therefore, even if a given GSX-R is not at 60 degrees to the vertical, weaving and bucking as its rear tire grabs for elusive traction in its natural habitat, who are we to judge its rider? There is no official right kind of fun. Maybe all that action is contained in the complete safety of the rider’s imagination. The choice of machine is just that, a choice. Motorcycles are symbols as much as they are vehicles.

Motorcycles are fun to ride because they multiply their riders’ abilities. Turning, braking and accelerating are thrilling and empowering at a basic level. The Gixxer tradition is rooted in this. The real goods are there, at throttle, brake lever and bars, whenever you want them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings, Rumblings

April 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRambling Roadblocks

April 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLet There Be Light

April 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley's Supercruiser Revolution

April 2001 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupVoxan On Track

April 2001 By Stephan Legrand