Battle of the Twins

RACE WATCH

KEVIN CAMERON

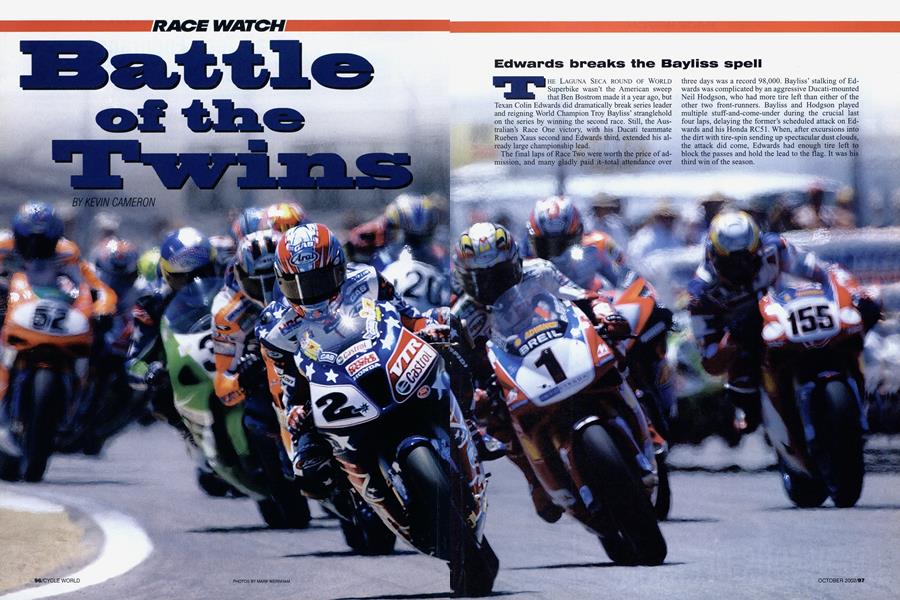

Edwards breaks the Bayliss spell

THE LAGUNA SECA ROUND OF WORLD Superbike wasn't the American sweep that Ben Bostrom made it a year ago, but Texan Colin Edwards did dramatically break series leader and reigning World Champion Troy Bayliss’ stranglehold on the series by winning the second race. Still, the Australian’s Race One victory, with his Ducati teammate Rueben Xaus second and Edwards third, extended his already large championship lead.

The final laps of Race Two were worth the price of admission, and many gladly paid it-total attendance over three days was a record 98,000. Bayliss’ stalking of Edwards was complicated by an aggressive Ducati-mounted Neil Hodgson, who had more tire left than either of the other two front-runners. Bayliss and Hodgson played multiple stuff-and-come-under during the crucial last four laps, delaying the former’s scheduled attack on Edwards and his Honda RC51. When, after excursions into the dirt with tire-spin sending up spectacular dust clouds, the attack did come, Edwards had enough tire left to block the passes and hold the lead to the flag. It was his third win of the season.

As suggested by this figure, the season has been a theater for Bayliss and his Ducati 998R, for as of Laguna he had won 14 of 18 races. At almost every challenge, Bayliss has simply dug deeper to take the lead and pull inexorably away. It is as though the spellbinding inevitability of this performance has mesmerized the others, transforming them from aggressive contenders into helpless spectators.

There was nothing helpless about the riding we saw from Edwards, from Hodgson, from Xaus or from Noriyuki Haga, all of whom showed the power, handling and riding skill to challenge the dominant Aussie. The difference was, in Race Two, Edwards made it stick.

Edwards is a straightforward person and not a corporate pup-on-a-leash barking ad slogans. When he says, “I’m riding that bike as hard as it can be ridden, so if they want it to go any faster, they know what it’s going to take,” I admire his candor and believe him.

In the first practice session, Edwards’ RC51 looked much as it did a year ago-stiff, busy and chattery. At that time, it had taken his bike seven laps to wear its tires to the point of visible sliding. Would it happen again? Edwards was nevertheless fast in this practice. The season-long question last year was this: Why would such a powerful company allow its bike to eat its tires, race after race? Some misguided internal policy? Development money going somewhere else? Bayliss in early practice was not visibly pushing, as if sizing things up, looking for the grip and the bumps. The musical Benelli was slow but stylish, rider Peter Goddard taking big lines, the usual 125cc rider’s substitute for horsepower. Haga on the Aprilia was also smooth and unhurried, as if the team were here only to put in an appearance. In the afternoon timed practice, Bayliss set a new record, a second faster than Edwards, who was eighth-quickest.

On Saturday morning, Bayliss continued to ride harder, but more interesting was the change in Edwards’ Honda. He was still using sweeping lines rather than pushing his bike into slides, but it looked much smoother and more settled. In the first 11 minutes of practice he rose to third-quickest-and then crashed on someone else’s big oil spill. He was fined 3000 Swiss francs for his initiative in jumping up and instantly red-flagging the practice. Edwards felt compelled to do this because of his experience in 1995, when his then-Yamaha teammate Yasutomo Nagai was killed in a crash caused by oil during a session that was not red-flagged.

When practice resumed, Bayliss began to do the things he’s famous for. As he flicked left-right in the steep descent of the Corkscrew, he hit his fairing with a loud crash on the inside-edge curb, then made the high-g pull-out to the right at the bottom, setting both wheels sliding in fine balance, his engine growling on heavy throttle. This is pushing grip deep into the sliding zone, using full suspension travel-in all, the very antithesis of stiff and chattery. As the bike wallowed once, wallowed twice, Bayliss launched his rollover to the left, using this rebound to make the slow-steering Ducati flick like a Kawasaki. The front end was sliding big here, but just as it seemed ready to call it quits, Bayliss would terminate the slide and change direction.

At that moment, I thought of the contrast between older-generation fighter aircraft like the F4 Phantom of the 1960s, whose angle-of-attack must be carefully limited to avoid stalling or rolling-out, versus today’s aircraft like the Russian Su-27, which somehow keep flying even with the nose at 90 degrees to the airflow. Bayliss was pushing both ends so deep, so hard, so smoothly that I stood there and grinned at his and Ducati’s accomplishment.

Friday night pit gossip said Honda had brought in a new chassis setup for Edwards. This was the new smoothness I had seen. Now in Saturday afternoon practice Bayliss switched modes, no longer doing hot laps but seemingly just riding around. After an initial work-up to fairly fast laps, he was concentrating on corners where special problems remained, no longer putting whole laps together. Bayliss had broken Anthony Gobert’s old qualifying record Friday with a 1:25.127, and Edwards had replied with a .022. Bayliss, putting it all together at last, and in the final moments, ran a stupefying 1:24.833. The order at the end of qualifying practice, but before Superpole, was Bayliss, Edwards, Hodgson, Bostrom and Haga.

Superpole is super-pressure-one timed lap, run solo after a warm-up lap. In Superpole practice, Bayliss crashed hard and was taken off in the ambulance. He would ride anyway.

Superpole is also a study in rider contrast. Xaus was hectic and wobbly on his Ducati, an incipient dust cloud. Kawasaki’s Eric Bostrom, who had just won the AMA Superbike race after a long pursuit by Nicky Hayden, braked to the

point of back-end weave, the bike still snaking as he stuck it into corners. Like its forebears, his ZX-7RR was very fast in roll-over. Doug Chandler, also riding as a Wild Card, was as smooth as ever in braking-to-comering transition. Haga, now riding his big lines much faster, was an impossible geometry lesson. PierFrancesco Chili, long a comer-speed man, brakes very stably. Ben Bostrom had the ill fortune to crash in Superpole, leaving the top three to have it out. Hodgson, pushing hard enough to provoke a big breakaway in Turn 4, rode to a 1:25.189. Then came Edwards, looking very stable and unremarkable as he ran a 1:24.888. First he waved his foot, then his hand, and finally added wheelies in celebration of winning pole. Bayliss, riding very square to his machine and looking a bit stiff after his earlier crash, could manage only a 1:25.301, despite hard flicking and a slide out of Turn 2.

Race One, however, was classic Bayliss. What are mere injuries in the face of rider determination? At the start, he shadowed Edwards, sometimes closely, sometimes farther back, but always able to close the distance. Edwards faced an unattractive choice: Ei-

ther race now, knowing this would fatigue his tires faster than it would those of the Ducati rider, or run just fast enough to prevent a Bayliss drive-off, conserving his tires for late-race action that might work to his advantage.

Haga climbed from seventh to take second from Bayliss in 10 laps. This made a lead group of six machines-Edwards, Haga, Bayliss, Hodgson, Hayden and Xaus. Ben Bostrom, so dominant last year, was sadly out of touch in seventh. Now Haga, slashing through Turn 2 on his invisible rail, paid the price of pushing really hard-he became dramatically horizontal, unable to work the line-tightening magic we’ve seen him succeed with so many times. Bayliss now had the job of making up the 15 bike lengths lost in battling with Haga.

It has been made clear all season which bike is kinder to tires: the Ducati with its strange wallowing grip and sliding balance. After 20 or so of the 28-lap race distance, Bayliss began to press Edwards, thrusting to first one side and then to the other. Up the hill leading to the Corkscrew, the Ducati had an acceleration advantage that allowed Bayliss to pull almost even. Why now and not earlier? First of all, he’d been busy with the Haga interruption. Second, you don’t test a baked potato for doneness after 10 minutes when you know perfectly well it takes 45 to cook. Like Valentino Rossi did last season in the 500cc Grands Prix, Bayliss would allow the difference in chassis “severity” to reduce his opponent’s tire grip, and then he would test for doneness.

This came about on lap 23, when both Bayliss and Xaus were in position to do the job off Turn 5, as Edwards’ rear tire broke traction. In quick action, Bayliss took the lead, then Xaus had it, then Bayliss again. Edwards, his tire finished, could only drop back, and Hayden closed behind him. That was the order at the end, with Hodgson completing the top five. Eric Bostrom was sixth, then Suzuki’s Aaron Yates, Ben Bostrom, Hodgson’s Ducati-mounted teammate James Toseland and Chandler.

“Did you look a bit shaky?” Bayliss was asked in the post-race interview. His smiling reply: “I was.” Edwards, donning his team cowboy hat and carefully positioning a Michelin cap on his helmet, commented, “We’re lackin’ a little bit of grunt out of the corners, but we knew that. I’ve never won here and it’s pissin’ me off. So it’s win or crash.”

On the Race Two warm-up lap, Xaus somehow crashed twice and had to start lap down. At the green light, Eric Bostrom led on his lately-much-faster Kawasaki-something supposedly impossible on a mere 750cc four-cylinder. It took Edwards three laps to pass him, and Bayliss another five to do the deed. The race seemed to converge on the same pattern as the first one-stalking by Bayliss, pressure, a pass and another win. But there were complicating factors. First of all, Edwards on his improved bike was running fast enough to fatigue

Bayliss’ tire, which had begun to let go during acceleration off Tum 11 as early as lap nine. Second, Hodgson, running in fourth for a long time, was now able to advance as his set-up proved more durable than that of his fellow Ducati rider. Just as Bayliss would have applied pressure to Edwards, Hodgson applied it to Bayliss. The result was an outburst of hand-to-hand combat, with Hodgson leading Bayliss on laps 26 and 27, and Bayliss having to dig deep just to regain second. Several times, the Australian’s rear tire said “no” out of Tum 11, while Edwards blocked pass attempts at the top of the hill. It was Colin’s race and he savored the win. A spectator handed him a big Old Glory on a stick, but this was not a flag cleared for high-speed service. It blew away, so Colin toured and made tire smoke for thousands of cheering fans.

“Feels sweet,” he said after the race, while Bayliss gallantly recited, “I lost out to a better man on the day.”

What changed in the Honda’s setup between Friday and Saturday practice? Engineers have played with chassis stiffness since the early ’90s, hoping to make chassis twist act as a “sideways suspension” to keep machines hooked up even at angles of lean that orient suspension at 60 degrees or more to the bumps they are supposed to absorb. Years ago, Yamaha cut a cross tube out of its 250cc GP bike to reduce

stiffness, and Honda RC30 Superbikes received the same treatment. In watching the Ducatis, Honda engineers felt the Italian steel-tube trellis frame was flexing quite a bit, giving Bayliss’ bike its distinctive wallow-and extra corner grip. How do you change chassis stiffness when rules require a stock frame? One clue is that Sunday afternoon, anyone who looked at Edwards’ two Hondas as they were readied for shipping would have been able, as I was, to look through open holes where the top-center engine bolt should have been. As the engine adds chassis stiffness, partially decoupling it would increase flexibility. Add to this World Superbike’s admirable history of gentlemanly compromise: “I won’t protest your suspected semi-legal parts if you don’t protest mine.” There may be more to this story than meets the eye-on both sides.

The big revelation of the weekend was that two tire makers-Pirelli and Michelin-are working with independent versions of a new class of manufacturing system that promises much for racing. Instead of manual layup of tire structure, positioning each element by hand, these systems wind or extrude them onto a building form via robots and computer control. In older systems, the “green” or uncured tire is driven outward into a fixed heated mold by an inner bladder. The new method brings the mold elements radially inward to the green tire.

This could be seen on some Michelins at Laguna, whose slick treads show marks where the mold’s 50 or so sectors join. This new process eliminates much of the migration of carcass elements that used to take place. The result is an extremely round and dynamically symmetric tire that can be made thinner because accuracy eliminates the need for extra material. Previously, tire-to-tire weight variations could be of the order of half a pound, but Pirelli’s MIRS production system holds tire weight within 5 to 10 grams, or .01-.02 of a pound. Thinner tires run cooler and therefore wear longer-paradoxical but true. They also lay down increased footprint area, and can employ softer, grippier tread compounds.

Cost cuts and flexible production (tire manufacturing can be moved to inside a vehicle-maker’s factory) were the driving forces of this change, but superior quality and consistency also yield attractive properties for racing and sports applications. Tire industry people are calling this, “A greater revolution in tire performance than the change from bias to radial construction.”

In a variant of this system, a tirebuilding form able to assume any desired profile is combined with post-cure shaving of the completed tire to allow tire variations that formerly required six weeks to now be made in a day. The faster you can perform experiments, the quicker you get answers.

I came away from Laguna feeling as if I’d eaten a huge and satisfying meal. The racing was grand, and remains the most potent source of ideas for the development of production motorcycles. The technologies of chassis, suspension and tires-so often neglected in the past-are now on the boil. And Colin Edwards has shown that he can do the job when he has the right tool. Just as he said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

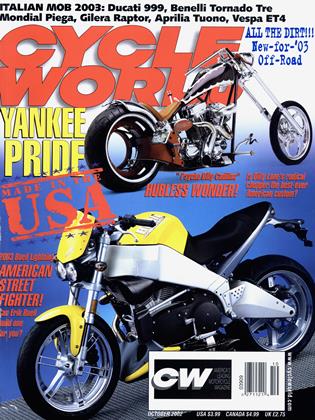

Up FrontI, Ducatista

October 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Tale of Two Suzukis

October 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCY-Alloy? Why Not?

October 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupCruising In Luxury: Bmw R1200cl

October 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupCentennial Harleys

October 2002 By Matthew Miles