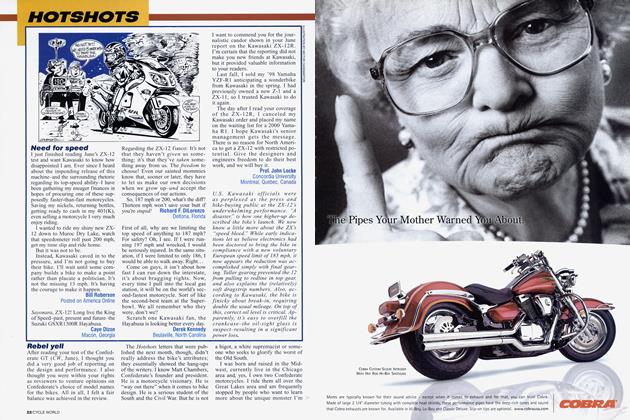

APRILIA TAKES CHARGE

ROUNDUP

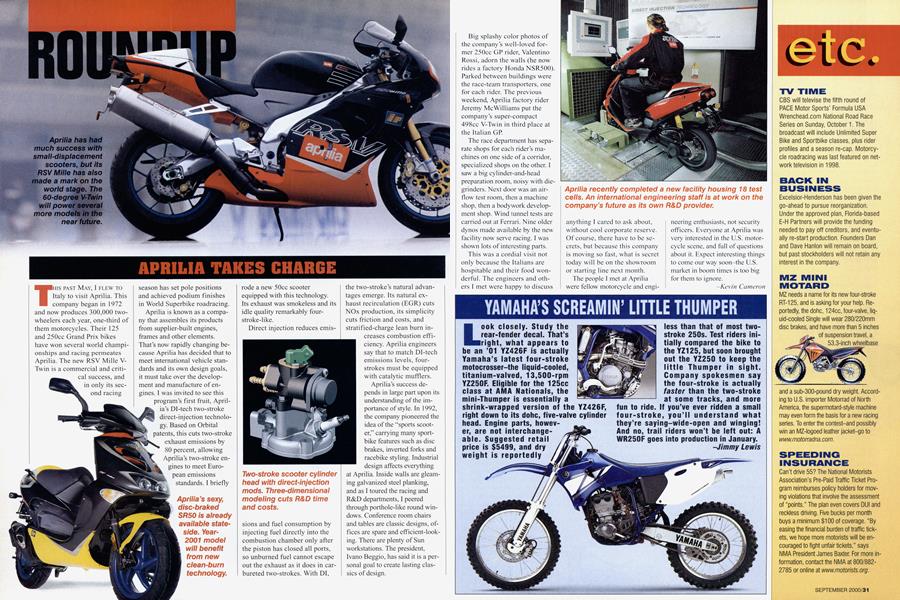

THIS PAST MAY, I FLEW TO Italy to visit Aprilia. This company began in 1972 and now produces 300,000 two-wheelers each year, one-third of them motorcycles. Their 125 and 250cc Grand Prix bikes have won several world championships and racing permeates Aprilia. The new RSV Mille V-Twin is a commercial and critical success, and in only its second racing season has set pole positions and achieved podium finishes in World Superbike roadracing.

Aprilia is known as a company that assembles its products from supplier-built engines, frames and other elements.

That’s now rapidly changing because Aprilia has decided that to meet international vehicle standards and its own design goals, it must take over the development and manufacture of engines. I was invited to see this program’s first fruit, Aprilia’s DI-tech two-stroke direct-injection technology. Based on Orbital patents, this cuts two-stroke exhaust emissions by 80 percent, allowing Aprilia’s two-stroke engines to meet European emissions standards. I briefly rode a new 50cc scooter equipped with this technology.

Its exhaust was smokeless and its idle quality remarkably fourstroke-like.

Direct injection reduces emissions and fuel consumption by injecting fuel directly into the combustion chamber only after the piston has closed all ports, so unburned fuel cannot escape out the exhaust as it does in carbureted two-strokes. With DI, the two-stroke’s natural advantages emerge. Its natural exhaust recirculation (EGR) cuts NOx production, its simplicity cuts friction and costs, and stratified-charge lean burn increases combustion effi-

brakes, inverted forks and racebike styling. Industrial design affects everything at Aprilia. Inside walls are gleaming galvanized steel planking, and as I toured the racing and R&D departments, I peered through porthole-like round windows. Conference room chairs

ciency. Aprilia engineers say that to match DI-tech emissions levels, fourstrokes must be equipped with catalytic mufflers.

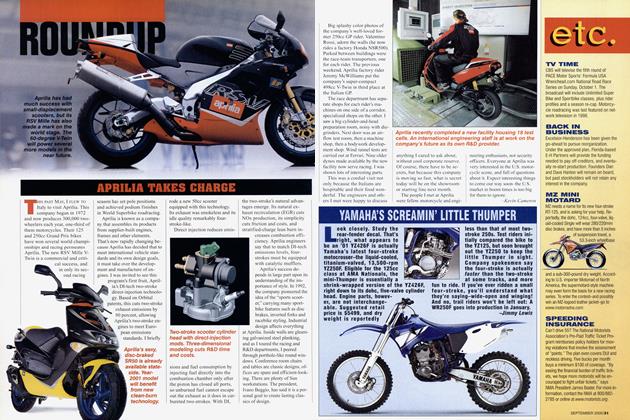

Aprilia’s success depends in large part upon its understanding of the importance of style. In 1992, the company pioneered the idea of the “sports scooter,” carrying many sportbike features such as disc

and tables are classic designs, offices are spare and efficient-looking. There are plenty of Sun workstations. The president,

Ivano Beggio, has said it is a personal goal to create lasting classics of design.

Big splashy color photos of the company’s well-loved former 250cc GP rider, Valentino Rossi, adorn the walls (he now rides a factory Honda NSR500). Parked between buildings were the race-team transporters, one for each rider. The previous weekend, Aprilia factory rider Jeremy McWilliams put the company’s super-compact 498cc V-Twin in third place at the Italian GP.

The race department has separate shops for each rider’s machines on one side of a corridor, specialized shops on the other. I saw a big cylinder-and-head preparation room, noisy with diegrinders. Next door was an airflow test room, then a machine shop, then a bodywork development shop. Wind tunnel tests are carried out at Ferrari. Nine older dynos made available by the new facility now serve racing. I was shown lots of interesting parts.

This was a cordial visit not only because the Italians are hospitable and their food wonderful. The engineers and others I met were happy to discuss anything I cared to ask about, without cool corporate reserve. Of course, there have to be secrets, but because this company is moving so fast, what is secret today will be on the showroom or starting line next month.

The people I met at Aprilia were fellow motorcycle and engineering enthusiasts, not security officers. Everyone at Aprilia was very interested in the U.S. motorcycle scene, and full of questions about it. Expect interesting things to come our way soon-the U.S. market in boom times is too big for them to ignore.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue