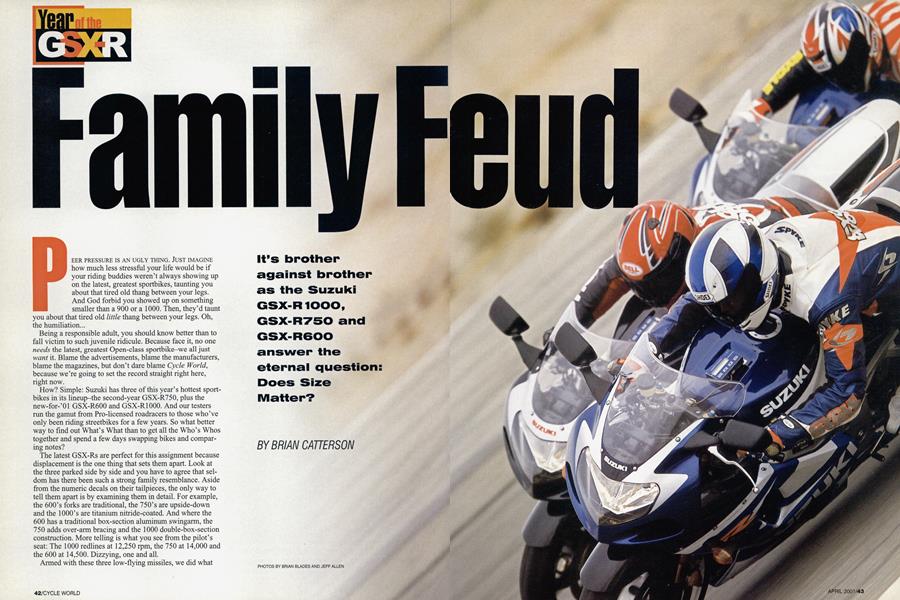

Family Feud

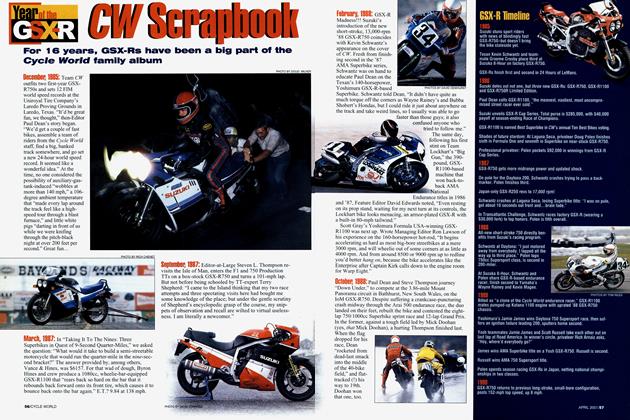

Year of the GSX-R

It's brother against brother as the Suzuki GSX-R1000, GSX-R750 and GSX-R600 answer the eternal question: Does Size Matter?

BRIAN CATTERSON

PEER PRESSURE IS AN UGLY THING. JUST IMAGINE how much less stressful your life would be if your riding buddies weren't always showing up on the latest, greatest sportbikes, taunting you about that tired old thang between your legs. And God forbid you showed up on something smaller than a 900 or a 1000. Then, they'd taunt you about that tired old little thang between your legs. Oh, the humiliation...

Being a responsible adult, you should know better than to fall victim to such juvenile ridicule. Because face it, no one needs the latest, greatest Open-class sportbike-we all just want it. Blame the advertisements, blame the manufacturers, blame the magazines, but don’t dare blame Cycle World, because we’re going to set the record straight right here, right now.

How? Simple: Suzuki has three of this year’s hottest sportbikes in its lineup-the second-year GSX-R750, plus the new-for-’01 GSX-R600 and GSX-R1000. And our testers run the gamut from Pro-licensed roadracers to those who’ve only been riding streetbikes for a few years. So what better way to find out What’s What than to get all the Who’s Whos together and spend a few days swapping bikes and comparing notes?

The latest GSX-Rs are perfect for this assignment because displacement is the one thing that sets them apart. Look at the three parked side by side and you have to agree that seldom has there been such a strong family resemblance. Aside from the numeric decals on their tailpieces, the only way to tell them apart is by examining them in detail. For example, the 600’s forks are traditional, the 750’s are upside-down and the 1000’s are titanium nitride-coated. And where the 600 has a traditional box-section aluminum swingarm, the 750 adds over-arm bracing and the 1000 double-box-section construction. More telling is what you see from the pilot’s seat: The 1000 redlines at 12,250 rpm, the 750 at 14,000 and the 600 at 14,500. Dizzying, one and all.

Armed with these three low-flying missiles, we did what anyone in our position would do: We lapped ’em at WillowSprings International Raceway, flogged ’em on the twisty mountain roads ringing the Antelope Valley, ran ’em through the quarter-mile at Los Angeles County Raceway and held ’em wide-open at our top-secret high-desert testing facility.

You’d expect the 1000 to be quickest around the roadrace track simply because of its greater horsepower output-a whopping 144.3 rear-wheel ponies at 10,500 rpm as measured on our dyno, compared to the 750’s 123.6 bhp at 12,500 rpm and the 600’s 103.5 bhp at 13,500 rpm. And with wing-footed Road Test Editor Don Canet in the saddle, it was, turning a best lap of 1 minute, 27.46 seconds. The other two weren’t far behind, however, the 750 turning a 1:27.85 and the 600 a 1:28.59. Hard to believe a 600 can give away 40 horsepower and still circulate the racetrack within a second and change.

Like the fighter pilot he probably would have become if it hadn’t been for poor eyesight, Canet has ice in his veins, and rarely shows signs of fear. (For that, you’ve got to get him on a motocross track.) But following his hot laps on the 1000, he was clearly distressed.

“After riding the 1000 at the Road Atlanta press intro, I wrote that it was stable and lightweight, but I’m kinda changing my mind now,” he said. “Maybe it’s the tires, but here the bike seems pretty twitchy, and feels quite a bit heavier than the other two.”

Part of this may indeed have been due to tires, because for the racetrack portion of our test we fit all three bikes with race-compound Dunlop D207GP Stars in 120mm front and 180mm rear widths. The 600 and 750 come stock with street-compound D207s in those sizes, but the 1000 comes with Bridgestone BT-110s, the rear a 190 on a wider, 6-inch rim. Even so, Dunlop assured us that its 180s are designed for both rim widths, so tire size shouldn’t have been an issue. And while it could be argued that the race tires’ stiffer carcasses made for a less compliant ride, the other two bikes worked just fine. Whatever the case, on the street, on the stock tires, the 1000 was as steady as a rock.

Prior to Willow, we didn’t think weight would be much of a factor, because all three GSX-Rs are flyweights, easily the lightest machines in their respective classes. On the certified CW scales, the trio weighed within 20 pounds-387 lbs. for the 600, 399 lbs. for the 750 and 407 lbs. for the 1000. But when rider after rider climbed off the 1000 and commented that the difference felt more like 40 or 50 pounds, we knew we were on to something.

A smaller-displacement motorcycle handles better than a larger one not just because of its lighter overall weight, but also because of the reduced inertia of the smaller, lighter crankshaft whirring about inside its crankcase. Spin anything at high rpm and it will resist turning; that’s why it’s harder to initiate a turn when a bike’s wheels are spinning fast than slow.

Now consider that the 1000’s engine is basically a longerstroke version of the 750’s, its 73.0 x 59.0mm cylinders giving it an old-school bore/stroke ratio of 1.2:1. Compare that to the 750’s 72.0 x 46.0mm, or the 600’s 67.0 x 42.5mm, and their more contemporary 1.5:1 ratio, and you’ll find that despite having the lowest rev limit, the 1000 achieves the highest piston speeds-as high as 4742 feet per minute on the rare occasion you dare run it to redline, compared to the 750’s 4226 fpm and the 600’s 4044 fpm.

To cope with the considerable vibration that results from such high piston speeds, the 1000’s designers gave it large, heavy flywheels and a balance shaft. Combine those with a cylinder head that is physically higher up on the motorcycle and a thicker-walled frame, and you’ve got a bike that is not only heavier, but has a higher center of gravity. You can feel this just by lifting the 1000 off its sidestand.

There are ways to combat crankshaft inertia’s effect on handling, but none are simple. Yamaha traditionally employed twin, counter-rotating crankshafts on its V-Twin 500cc Grand Prix racers, and its machines were always said to turn-in better than its single-crank opposition. The GSXR1000 has just one crankshaft, but it has a counter-rotating balance shaft that spins at twice crank speed-an astronomical 24,500 rpm at redline-which helps but does not eliminate this phenomenon.

A more pertinent factor is the different manner in which you ride an Open-class sportbike around a racetrack. At one point during our day at Willow, Canet caught up to me entering 140-mph Turn 8, and later commented that I got through there really well on the 600, whereas he was having difficulty with the 1000. The reason was clear: On the smaller, slower bike, I could just hold the throttle to the stop, whereas on the bigger, faster one he was having to roll off. This loaded the front end, made the tire deflect off bumps, and made him want to roll off even more-a vicious cycle. Cracking the throttle open even slightly settles a motorcycle’s chassis, but that’s the last thing on your mind when your bike is misbehaving while you’re railing through a comer with your knee on the ground at what seems like a million miles per hour.

Paradoxically, the 1000 was the least and most demanding bike to ride, on the racetrack as well as the street. On the one hand, its greater torque output-75.8 foot-pounds at 8250 rpm, compared to the 750’s 57.5 ft.-lbs. at 10,000 rpm, and the 600’s 46.1 ft.-lbs. at 10,500 rpm-makes the engine much more flexible. As a result, you almost never have to shift, and could probably tum a respectable lap time in just fourth gear. On a winding road, you can just stick it in one gear-second, third, fourth, your choice-and surf the L~ mondo waves of torque. That wealth of midrange grunt also lets you be a little lazy, instantaneously gaining back at the corner exit whatever entrance speed you may have sacri ficed, just by dialing on the throttle.

But that's a double-edged sword, because anytime you turn that twistgrip, things happen in a real hurry. In a word, the GSX-R1000 isf-a-s-t, and like a GSX1300R Hayabusa, seems to accelerate harder the faster it goes. But if the Gixxer accelerates like the `Busa, it couldn't handle more differently; it steers like a racebike, not a bus. -

Guest tester Mark Cernicky was suitably impressed. "It's a good thing I've been racing an Ri at Willow, because with out that, it would have taken me a lot longer to get up to speed on the GSX-Rl000," he said. "The Suzuki is so fast that you tend to brake early, but you can actually carry a lot of entrance speed."

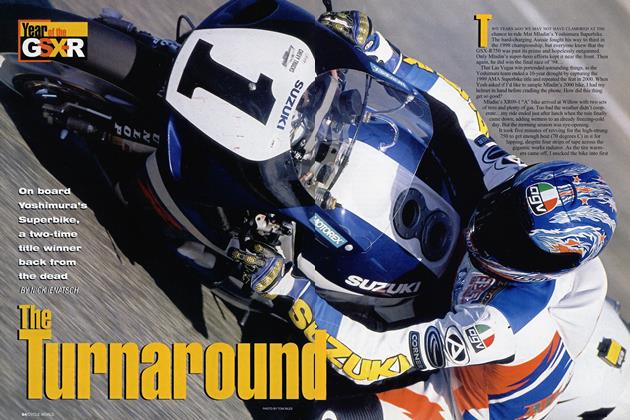

Contributing Editor Nick Ienatsch echoed Cernicky's sentiments: “The first time I went through Turn 6 on the 1000 it wheelied over the crest, which is pretty impressive. That’s something usually only racebikes will do. It takes a lot of horsepower.”

All that power means you’ve got to show some serious right-wrist restraint. Turn the throttle too hard, and you’ll be wheelying quicker than you can say, “Ohmygodr Do so while leaned over in a tum, and the back end steps right out. That’s fine if you’re a racer accustomed to finishing comers by rear-wheel steering, but it’s unnerving for mere mortals.

Managing Editor Matthew Miles hadn’t been to Willow in over a year, and so gravitated toward the 600. “The biggest thing to me was how much of a difference there was between the 600 and the 1000,” he said. “The 1000 was intimidating. The 600, on the other hand, just felt easy to ride.”

Miles spoke for the group, because we all found the 600 unintimidating. Forget for a moment that it has the most powerful motor in the middleweight class; compared to the two bigger GSX-Rs, it just felt usable. With its high-revving engine you need to row the six-speed gearbox constantly, but its smooth delivery makes putting the power to the ground an unworrying proposition. And as the lightest four-cylinder sportbike on the market, it handles flawlessly. Never before has a bike been so unaffected by mid-comer bumps, or so willing to change lines.

Assistant Graphic Artist Brad Zerbel doesn’t get out on sportbikes much (we bring him along because he brews his own beer), and like Miles was initially drawn to the 600. But he changed his tune as soon as he rode the 750.

“The thing I noticed about the 750 is that if I left it a gear high, it would still pull out of the comer, whereas the 600 would hardly accelerate,” he noted.

Though the 750 feels very much like the 600, it has power to spare. It lives to rev, but its engine is noticeably more flexible, so that you don’t have to spend as much time shifting and wringing its neck. And while, yes, the 1000 is faster, the last thing you’d ever call the 750 is “slow.” To the contrary, it’s faster than most Openclassers, including the vaunted Honda CBR929RR and Yamaha YZF-R1. Maybe we got it right when we named the GSX-R750 Best Superbike of 2000?

As Murphy’s Faw would have it, the ominous dark clouds that hung overhead the morning of our track test began dumping on us after lunch, this following two consecutive months of sunny, 80-degree days. An incessant drizzle gradually gave way to outright rain, and Miles stayed out one lap too long on the 600, eventually losing grip and high-siding exiting Turn 9.

Even in the wet, his speed at that point was close to 95 mph, and the ensuing carnage resembled a plane crash. Matt was lucky to escape with a broken wrist, but the bike barrel-rolled into oblivion, scattering parts as it went. Mass centralization does great things for handling, but bikes sure seem to crash worse nowadays.

Considering that Canet had done similar damage to a GSX-R1000 at the Road Atlanta press intro, we opted to preserve our relationship with Suzuki, park the other two bikes for the remainder of the day and adjourn to the nearby Golden Cantina for margaritas.

Fortunately, we put a lot of miles on the 600 before we put Miles on the 600, so rolling it into a ball had minimal impact on our testing. Canet and I spent three days with the bike at the Road Atlanta press intro, including lots of street miles, and staff masochist Mark Hoyer rode it all the way to Texas (!!!) for CIFs upcoming Travel & Adventure special issue. So if we going to wad one, this was the one to wad.

The following morning’s top-speed testing again the 1000 assert its dominance, running an eyewatering 175 mph compared to the 750’s 168 mph. The 600-or what was left of it-stayed in the truck, but it had gone 156 mph at the same venue a month prior.

It was the same story at the dragstrip, where the 1000 ran a blistering 9.95-second quarter-mile at 143.69 mph. That’s just nine-hundredths of a second slower than CIT’s all-time quarter-mile champion, the Hayabusa 1300!

Mind you, Canet had a tough time of it, as the GSXR’s short wheelbase (55.8 inches, 2.7 inches shorter than the ’Busa’s) made it exceptionally wheelie-prone. Leaving the line, the bike would simultaneously spin the tire and wheelie, settle down, then do it all over again. Canet had a much easier time with the 750, and clocked a 10.38-second run at 135.49 mph. Again, the 600 was incapacitated, but previous testing at Atlanta Dragway had shown it was capable of running a 10.76 at 127.95 mph.

So, in terms of outright performance, the GSXR1000 is the clear-cut winner, notching victories in every performance category. If you’re one of those dedicated individuals for whom only the latest, greatest sportbike will do, look no farther. But there was one category in which the 1000 didn’t dominate: Call it accessibility, user-friendliness, the spode factor... whatever.. .but in these days of ultra-high-performance sportbikes, you can’t overlook the rider. And unless you’re a highly skilled operator, the 1000 is just too much motorcycle.

If you’re an outright beginner, the 600 is probably too much motorcycle for you, too. Yes, it’s “only” a middleweight, but it makes more than 100 horsepower, which was the domain of Open-classers not too many years ago. Better to start on something smaller and friendlier, like an SV650. For those just moving up to a serious sportbike, however, the 600 is the most viable choice in this group.

Between the 600 and 1000 stands the bike that combines the best of both, the “just-right” 750. Three decades ago, Honda gave us the CB750 Four, and for years thereafter 750s were heralded as the perfect-sized motorcycle. Never mind the proliferation of lOOOcc V-Twins brought about by modem Superbike racing mies, that’s still tme today. The chasm that used to exist between middleweights and Open-classers has virtually vanished, but the happy middle ground is still the happy middle ground. And that’s why for most sport riders, the best Suzuki is the GSX-R750.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings, Rumblings

April 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRambling Roadblocks

April 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLet There Be Light

April 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley's Supercruiser Revolution

April 2001 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupVoxan On Track

April 2001 By Stephan Legrand