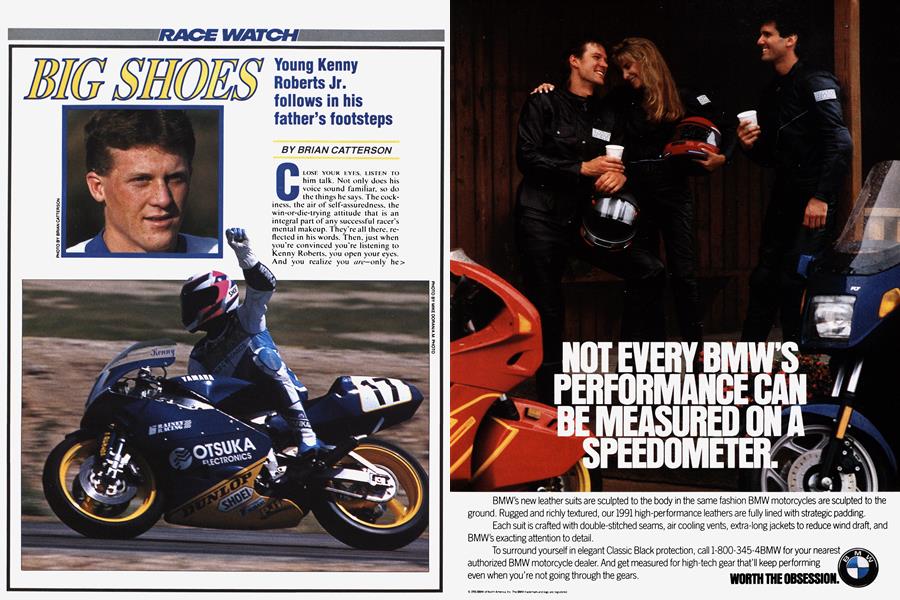

BIG SHOES

RACE WATCH

Young Kenny Roberts Jr. follows in his father’s footsteps

BRIAN CATTERSON

CLOSE YOUR EYES, LISTEN TO him talk. Not only does his voice sound familiar, so do the things he says. The cockiness, the air of self-assuredness, the win-or-die-trying attitude that is an integral part of any successful racer's mental makeup. They're all there, reflected in his words. Then, just when you're convinced you're listening to Kenny Roberts, you open your eyes. And you realize you are—only he> looks far younger than you rememher him. No, you haven't gone back in time, this is Kenny Roberts, all right. Kenny Roberts Junior. Born July 25, 1973. young Kenny is the son of the three-time world

champion and his first wife, Patty. Today, he lives with his father, his stepmother, his two younger brothers and his grandparents on a ranch in the central California countryside.

And he has a secret: Although he’s now known as Kenny Roberts Junior, a.k.a. “K.R.JR.,” son of perhaps the greatest motorcycle racer of all time, he technically isn't a junior. “My dad's middle name is Leroy, mine’s Lee,” he explains, “so I'm really Kenny Roberts II. But everyone calls me Junior.”

Roberts Jr. started riding at age 2, and spent the first five years of his life traipsing around Europe while his dad chased world championships. His first motorcycle, a present from his grandmother, was a 50cc Moto Beta dirtbike, but almost from the beginning he preferred roadracing machines—albeit the “pocket bikes” that were once popular as pitbikes. But in spite of his early start, young Kenny wasn't bitten by the racing bug himself until he was 14. first race weekend. And he dominated his first time out as an Expert as well, putting his YSR racing skills to good use to win five races on the short, tight Streets of Willow Springs.

“I went to the AMA National at Sears Point in 1989. and w hen 1 saw how John Kocinski dominated, I wanted to do it just like him.” he remembers.

Roberts won his first-ever race, a one-hour rough scrambles marathon at the nearby Lodi Cycle Bowl. He then began racing Yamaha YSR50 minibikes, and did so with such success that he qualified for—and won — the 1989 national championship in the Amateur class.

His move to full-size bikes came in the spring of 1 990. Offered a ride on a Yamaha FZR400. Roberts won his mandatory Novice race during his

Over the next four months, young Roberts became a contender in the ARRA's 400cc Production class. And then, in November, he got his first real help from his dad —an opportunity to ride Rich Oliver’s Marlboro Yamaha TZ250. And with that, he became competitive in the Fl and 250cc GP classes. Kenny Roberts Junior had arrived.

Over the winter, he received an offer of a ride that would vault him to national prominence. His father said he’d been contacted by a team that wanted to sponsor Kenny Jr. in WERA’s newly formed F-2 class. And although he didn’t know it at first, the team owner was none other than world champ Wayne Rainey.

“Wayne called me on the phone one night and asked me if I knew who the team owner was,” Roberts says. “When I told him that I hadn’t heard yet, he said, ‘Well, it’s me.’”

The new team, Rainey Racing, was formed with sponsorship from Otsuka, a Japanese electronics firm. Joining Roberts on the team’s Yamaha TZ250s is fellow Californian Allan Scott, a former I25cc grand prix contender.

The team strategy calls for Roberts to spend the year learning, and for Scott to win the championship. So far, both riders have lived up to expectations. As of this writing, Scott leads former AMA Formula 2 champ Donnie Greene atop the series point standings. And Roberts, with a learning curve as steep as a Ill's takeoflf> climb, lies a credible third.

Roberts’ lessons began at Road Atlanta, where he finished fifth behind a flock of more experienced rivals. He improved on that by finishing third in the next race at his home track of Willow Springs. It was there that he achieved his first real notoriety, as he provided TV viewers with dramatic footage as he recovered from a blatant front-tire slide.

“That was just wrong-line material there,’’ he recalls, vividly. “I remember going in wide, and as I did, all I remember is the front tire going, it seemed like for hours. I started pushing my knee down harder, and before I knew it, I was looking back to see where the track had gone.’’

In the next round of the series, at Seattle, Washington, Roberts Jr. crashed during a race for the first time while trying to make up for his machine’s shortcomings.

“We had a problem with carburetion, and we were down on top speed,” he explains. “I went down the straightaway in Allan’s draft and> it shot me into the corner too quick. 1 went low to scrub off speed and hit some bumps. Before I knew it. 1 was sliding along on my back.”

Did he perhaps crash trying to impress his father, who was present at Seattle? He says not.

"Once I get on the bike, everything else is gone from my mind. I don’t think I've got to get first place just because my dad's there. I want to win anyway. It comes down to how much pressure you put on yourself.”

At Shannonville. Canada, Roberts raced in the rain for the first time. But he finished seventh nonetheless, earning maximum points for being the first American in the combined WERA/RACE event. Clearly, he had proven that he had the ability to adapt to varying track conditions. To what does he attribute this skill?

“A lot of my dirtbike and YSR experiences cross over,” he says. "Riding in the rain at Shannonville, with the thing sliding all over the place, didn't bother me at all.”

But how much of that skill is learned, and how much is inherited from his father?

"I learned everything basically on my own,” he says, defensively. "My dad will tell me what I'm doing wrong when I ask him to. But, basi^ cally. it’s just miles on the bike.”

He doesn't deny, however, that he is gifted. "As far as natural ability, I can go out there and pick up 3 seconds just following somebody around. That’s as natural as you can get. And that save at Willow was definitely all instinct.”

There are times, though, when his> dad will comment on his riding without being asked. “When he watched me race at Seattle, he told me he doesn't want me stuffing people as much, because you can get hurt, and you don't want to get that kind of a reputation."

Roberts' rookie season took a turn for the worse at Brainerd, where he soldiered home ninth, his bike running on one cylinder due to electrical problems. And although matters started off poorly—with a crash in practice-in his most recent race at Poco no, Roberts recovered to finish second despite losing his tachometer during the race.

It s been a season of highs and lows, and although there are still two races left in the season. Roberts displays a philosophical attitude about the year to date.

“It's been a time for learning, and we're just now getting the bad part of the learning. The good will start coming around. We'll see what comes next."

What’s next should definitely be good. Bud Aksland, who's done much of the development work on Yamaha’s GP bikes, has been dynotuning Roberts Jr.'s bikes in preparation for the next round of the WER A series, at Moroso in Florida, so Roberts should finally have equipment to match his abilities.

Because of who his father is, young Kenny has found himself in the spot^> light. But he has taken the attention in stride and says that, so far at least, there have been no accusations of him being given an unfair advantage.

“There are a lot of guys who might think that, but no one’s said anything. I could see if I had a factory hike and was riding around in 13th place. Then you could say that. But I’m riding my ass off to finish in the top three. I'd just tell 'em let's swap bikes and see who wins then.”

What about down the road? What are Roberts’ long-term goals? Stupid question. ”1 want to become 500cc world champion. My dad’s done it and I'm going to do it.

“1 want to win the WERA F-2 Championship next year, and then the year after that, race the season over here plus a few GPs. And then do the 250cc world championship the year after that. II' 1 get a good bike and I get the experience and I don't get hurt, I think I can win it. I don't see any reason why I can't,” he says.

And, if everything works out. will he he riding for his dad? ”1 hope so. I definitely think so. as long as he stays in racing, which I think he will.”

In the meantime, Roberts Jr. spends his off-track time doing the things most 18-year-olds do: hanging out with his girlfriend, going to the movies and concentrating on his 12th-grade studies. But there are a couple of differences, as he explains. “I draw the line at partying,” he says. “If you’re going to he dedicated to something, you've got to do it> right. I've never drank a beer and I've never smoked anything, so I don't know or care what I’m missing.

“As for school. I'm going to night school twice a week so I can get my diploma a semester early in January. I just want to get out of there so I can go racing.”>

And what of his dad? How does King Kenny feel about Prince Kenny racing motorcycles?

"He made up his mind he wanted to do it. so there's no stopping him now. only helping him." the senior Roberts says. "It's hard to say how you feel about your son following in your footsteps in a sport as dangerous as this. It's been good to me. though, so I shouldn't say anything."Then, Kenny Roberts the world champion racer gives way to Kenny Roberts the father. He thinks fora moment, and adds, smiling, "But I would have preferred he'd taken up golf.” E!

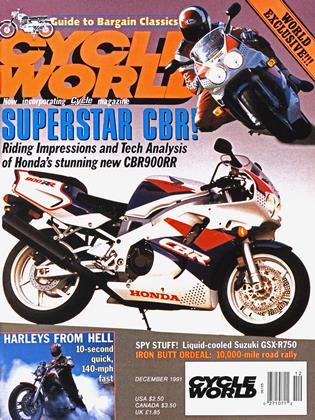

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

December 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1991 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

December 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

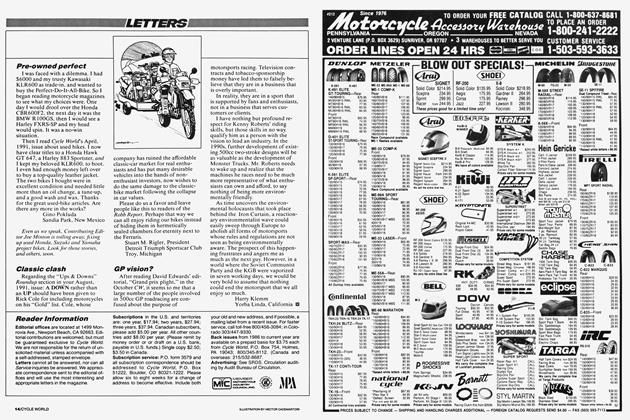

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1991 -

Roundup

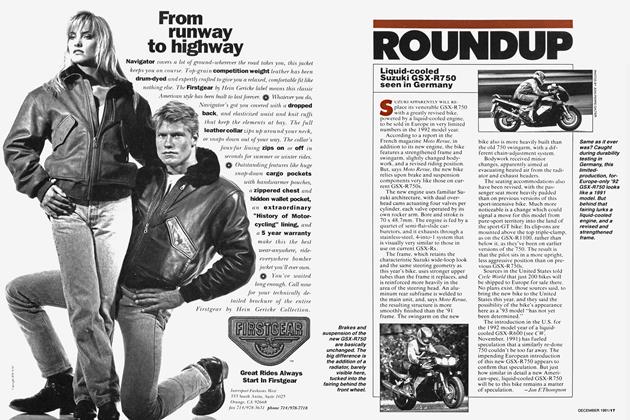

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Suzuki Gsx-R750 Seen In Germany

December 1991 By Jon F.Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Reinvents the Rokon

December 1991 By Jon F. Thompson