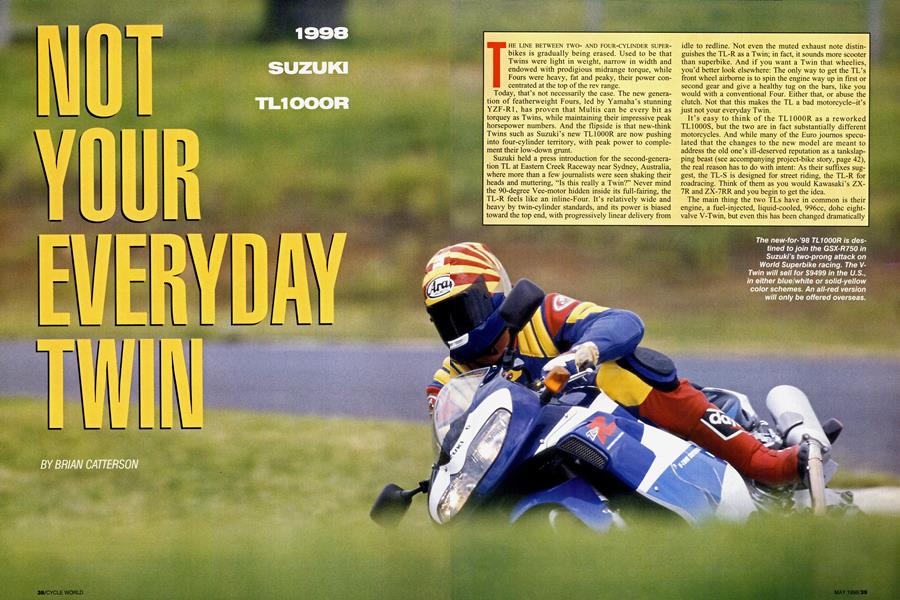

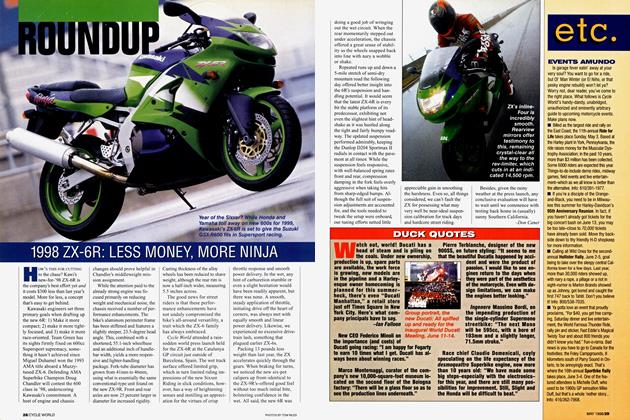

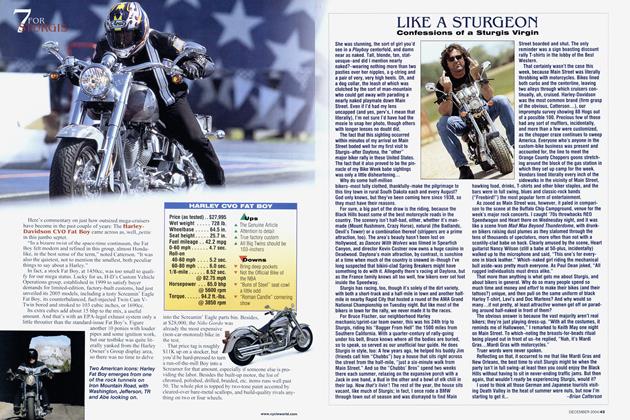

NOT YOUR EVERYDAY TWIN

1998 SUZUKI TL1000R

BRIAN CATTERSON

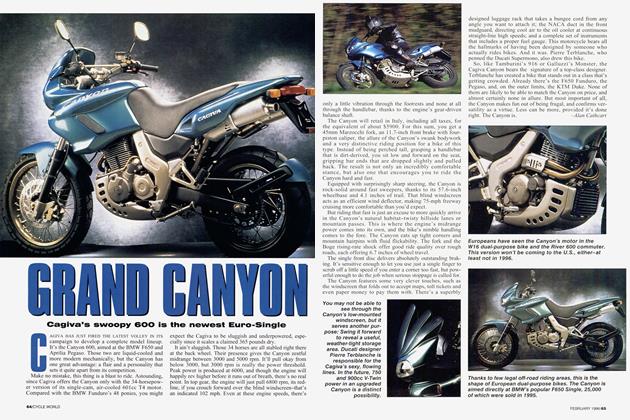

THE LINE BETWEEN TWO- AND FOUR-CYLINDER SUPERbikes is gradually being erased. Used to be that Twins were light in weight, narrow in width and endowed with prodigious midrange torque, while Fours were heavy, fat and peaky, their power concentrated at the top of the rev range.

Today, that’s not necessarily the case. The new generation of featherweight Fours, led by Yamaha’s stunning YZF-R1, has proven that Multis can be every bit as torquey as Twins, while maintaining their impressive peak horsepower numbers. And the flipside is that new-think Twins such as Suzuki’s new TL1000R are now pushing into four-cylinder territory, with peak power to complement their low-down grunt.

Suzuki held a press introduction for the second-generation TL at Eastern Creek Raceway near Sydney, Australia, where more than a few journalists were seen shaking their heads and muttering, “Is this really a Twin?” Never mind the 90-degree Vee-motor hidden inside its full-fairing, the TL-R feels like an inline-Four. It’s relatively wide and heavy by twin-cylinder standards, and its power is biased toward the top end, with progressively linear delivery from idle to redline. Not even the muted exhaust note distinguishes the TL-R as a Twin; in fact, it sounds more scooter than superbike. And if you want a Twin that wheelies, you’d better look elsewhere: The only way to get the TL’s front wheel airborne is to spin the engine way up in first or second gear and give a healthy tug on the bars, like you would with a conventional Four. Either that, or abuse the clutch. Not that this makes the TL a bad motorcycle-it’s just not your everyday Twin.

It’s easy to think of the TL1000R as a reworked TL1000S, but the two are in fact substantially different motorcycles. And while many of the Euro journos speculated that the changes to the new model are meant to address the old one’s ill-deserved reputation as a tankslapping beast (see accompanying project-bike story, page 42), the real reason has to do with intent: As their suffixes suggest, the TL-S is designed for street riding, the TL-R for roadracing. Think of them as you would Kawasaki’s ZX7R and ZX-7RR and you begin to get the idea.

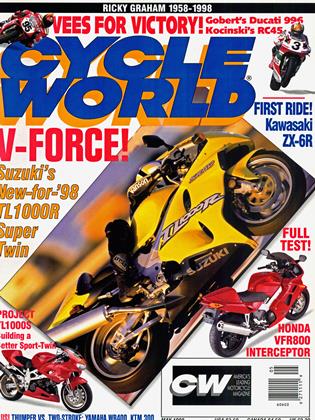

The main thing the two TLs have in common is their engine, a fuel-injected, liquid-cooled, 996cc, dohc eightvalve V-Twin, but even this has been changed dramatically for use in the R-model. Biggest difference is the new bike’s 11,000-rpm redline (up from 10,500), and greater power output: Suzuki claims an increase of 7 horsepower for a total of 135 bhp at 9500 rpm at the countershaft. In realworld terms, that should translate to around 120 bhp at the rear wheel, right up there in YZF-R1 territory.

The performance improvements were achieved through traditional means, such as hotter cams, lighter forged pistons, carburized connecting rods and a redesigned crankcase that minimizes mechanical losses by keeping the primary gears from drowning in oil. Since higher revs typically result in higher heat, twin radiators are now fitted, one stacked atop the other behind the front wheel with the forward cylinder’s exhaust cam poking out between (a la Ducati 916) in the interest of maintaining a narrow frontal area. A liquid-cooled collar beneath the spin-on oil filter keeps oil temperatures in check, while a new, hydraulically actuated eight-plate clutch with a backtorque eliminator puts the power to the rear wheel via a close-ratio six-speed transmission.

Another noteworthy upgrade concerns the fuel-injection system. Twin injectors now squirt fuel into each cylinder, with one injector working full-time and the other kicking in only at high rpm, as is the case with many twin-carb Singles. The engine inhales through dual ram-air ducts feeding a large, flapper valve-equipped airbox, like that fitted to the TL1000S and the ’98 GSX-R750. There’s also new injection mapping, with separate highand low-rpm maps for each injector, for a total of eight. Exhaust exits through a new 2-into-2 system, with a pair of aluminum muffler canisters bending upward to end just above the rear tumsignals, in the interest of maximum cornering clearance and tidy aerodynamics.

Chassis-wise, the TL1000R is all-new, with an aluminum twin-spar frame replacing the S-model’s oval-tube setup. As a result, the spring for the rotary-style rear damper had to be relocated from alongside the engine to behind it, with the battery repositioned along the engine’s left side; removing a couple of screws in the fairing lower accesses the battery.

Though the TL-R employs a rotary-style damper, it is different than that fitted to the TL-S. The rebound and compression damping adjusters have been relocated so that now you can get a screwdriver on them, and motocross-derived temperature-compensating needles give the damper consistent performance even after the oil gets hot and thins. A new, stiffer aluminum bridged swingarm rounds out the rear suspension setup.

Up front, there’s a fully adjustable Kayaba 43mm inverted fork, mated to a pair of Tokico six-piston calipers grasping 320mm rotors. The Australian-spec TLs we rode during our track test were shod with race-compound Metzeler MEZ1 steel-belted radiais, but U.S. models will roll on Dunlop D207s similar to those fitted on the GSX-R750 and YZF-R1. Sizes are 120/70-17 front and 190/50-17 rear, the latter spooned onto a 6-inch-wide rim.

Tires played a crucial role in determining our first impressions of the TL-R. Anticipating hot action on the racetrack during the two-day intro, the Metzeler technicians initially lowered pressures to 28 psi front and rear. Unfortunately, they’d failed to take into account the scorching-hot weather of the Down Under summer, and the journos were soon slippin’ and slidin’ all over the place. Raising pressures to 32 psi front and 30 psi rear improved traction considerably in the remaining sessions, particularly when the blazing sun ducked behind the clouds.

With the tire situation resolved, we were then free to focus on suspension tuning. Initially, there was way too much sag in the rear end (our 200-pound tester saw a whopping 43mm on the bike he measured), which resulted in excessive squat at corner exits and wallowing in fast sweepers. Raising shock-spring preload two full turns gave the rear end the proper attitude, and subsequent dialing-in of the front ride height (we pulled the fork tubes up 2mm in the triple-clamps-any more and the fender would have hit) and damping adjusters got the bike handling like a racebike should.

Compared to the TL-S, the TL-R feels just a bit racier, due to fractionally lower handlebars. The new bike also is slightly heavier-steering, and significantly more stable at speed. Some of this is due to more-conservative rake and trail figures, and some to the addition of a steering damper, but it also has to do with the rider having more of his weight over the front end. This effectively lowers the center of gravity, making the bike easier to bend into a comer and giving it a more planted feeling as you rail through. Trail-braking also has noticeably less effect on your ability to tum-in.

As is the case with many fuel-injected bikes, it’s important to exercise precise throttle control from mid-comer on. Ham-fisted throttle-twisting causes the chassis to pitch fore and aft, severely hindering your drive. Turn it on slowly and you’ll reap the benefits, however, as the TL puts the power to the ground like only a V-Twin can. Even when the tires got greasy, and the rear end started breaking loose exiting comers, the TL proved easy to control, with smooth, predictable slides the order of the day. These antics sometimes forced us to short-shift, though, to keep the engine from prematurely getting into the rev-limiter.

The R-model’s comparatively lackluster bottom-end and midrange power delivery could be viewed as a deliberate attempt to prevent it from tankslapping, but this is at best partially correct. Read the racing press these days and you’ll hear Ducati Superbike pilots Carl Fogarty and Troy Corser complaining that their 916s have too much bottom-end gmnt, which causes the front wheel to get light and the bike to run wide exiting comers. The accepted solutions are to put more weight on the front wheel (impossible with Ducati’s current engine) and/or soften the bottom-end hit by shifting the power higher up the rev range. Sound familiar?

While the TL’s powerband is largely determined by cam timing, it’s also affected by fuel-injection mapping. And as American Suzuki’s tech-head-turned-PR-manager Mark Reese explained, because the TL-S was criticized for poor fuel mileage and range, Suzuki purposely leaned-out the TL-R through the midrange to boost mpg. Adding fuel in that region via a programmable EFI module (such as the one in the available race kit or a Dynojet Power Commander) likely would return some of the lost midrange poop, though it’s doubtful that it will ever rival that of the TL-S.

And that, in a nutshell, pretty much describes the TLIOOOR. Much as we enjoyed riding it at the racetrack, we can’t see where street riders would choose it over the TLIOOOS, which offers better real-world performance while costing $500 less (and now including $400 worth of free accessories). Furthermore, while we haven’t yet had a chance to compare the TL-R directly to the competition, our seat-of-the-pants impressions suggest that Ducati’s 916 and Yamaha’s YZF-R1 would both be quicker around a racetrack. In fact, the TL’s closest competition likely will come from Honda’s CBR900RR and Suzuki’s own GSX-R750.

What the Suzuki TL1000R is, is a victim of poor timing, arriving at a time when it faces stiff competition from all quarters. Had the TL-R debuted last year, it probably would have been proclaimed the year’s hottest new superbike. Alas, it now is merely a very capable, somewhat bland sporting streetbike, whose sales success likely will be determined by its results on the racetrack. We wish it well.