COMING -AMP;AMP; GOING

Notes from the grass at the Legend of the Motorcycle Concours d'Elegance

KEVIN CAMERON

AT THE MOMENT I FEEL A BIT LIKE I’M A COMET THAT HAS sailed in from deep space to whip tightly around the sun, then begun the long trip out again. I just attended the Legend of the Motorcycle Concours in Half Moon Bay, California, where I walked up to a 1956 MV Agusta four-cylinder Grand Prix bike and standing next to it was Nobby Clark. There is no greater repository of racing lore anywhere in the known universe, as this man worked with Redman, Hailwood, Agostini, Roberts, Lawson and others. The things I only wish I knew, Nobby Clark knows.

Nearby was the Honda RC181 four-cylinder 500cc racer for which Mike Hailwood had Ken Sprayson make a special chassis. In 1967,

I saw Hailwood’s factory 500 go into high-speed weaves on corner exits at the Canadian GP at Mosport, in Ontario. Forty-some years later, kneeling in the grass (this concours took place on a golf course) for a better view, I could see the single large downtube that is the central feature of this chassis extending back just below the large underengine oil sump.

I asked Nobby if that was the original fork, a spindly looking affair with small tubes, a cast-steel single-pinch-bolt lower crown and axle slightly offset to the front (by about 10mm)-not much different from what you’d see on a stock CB72 Hawk 250 streetbike of that time. Yes, he said, that was the right fork. Upon returning home, I found in a book a photo of what was probably that very bike in its preSprayson form (no large downtube) with the offset-axle fork, visually the same as I’d seen in Half Moon Bay.

I remembered that the early Honda 250 Fours had trouble with high oil temperature, so I asked Nobby about this. He said that at the fastest tracks-Spa and Monza-the oil came close to 200 degrees Centigrade (392~ F) and that a return line to the external tank had burst; its rubber gave up under that temperature. The solution was oil-coolers, which I remember seeing hanging from their lines when the fairings were off at the Canadian GP.

Nearby was a Marvel motorcycle, manufactured in 1911 in Hammondsport, New York-Glenn Curtiss' town. The bike had a Curtiss engine with a single rocker arm operating both

valves by a push-pull rod. When the rod pushed, the rocker depressed the exhaust stem. When it pulled, the rocker opened the intake. Thus, no valve overlap was possible. No less a designer than Ferdinand Porsche penned a V-Eight in 1910 with this feature; indeed, it had a brief period of fashion. That ended abruptly when one of the regulars at Britain's Brookiands Speedway, Victor Horsman, suggested to a friend, G.E. Stanley, that he interchange his Singer's intake and exhaust cams. The resulting timing, which had valve overlap, worked so well that it killed the mechanically neat single-rocker valve system dead.

There was another interesting feature: Standing to the left of the bike, I could see that the engine’s cylinder was forward of center on the crankcase by maybe a half-inch. This was a common tuning technique in France at that time and is still practiced today. Offsetting the cylinder reduces the angularity of the con-rod on the power stroke, thereby slightly reducing friction.

Thirty years ago, I wouldn’t have cared about these machines. I was busy building racebikes and history was irrelevant. Somehow that changes, and I’m not talking about nose-blowing nostalgia. I now want to know how time’s arrow flies, not just look at its small cross-section in my own moment.

The Velocette before me is a good example. Its nearly vertical front downtube got that way from mass-placement experiments made by Velo’s race team in the 1930s. Today, R&D means keyboard hotties seated at workstations or long rows of test cells. Back then, it was a few men with questions, a bike, a race circuit, rider Stanley Woods and some lead weights taped to the chassis in various places. What they learned became Velo’s far-forward engine placement.

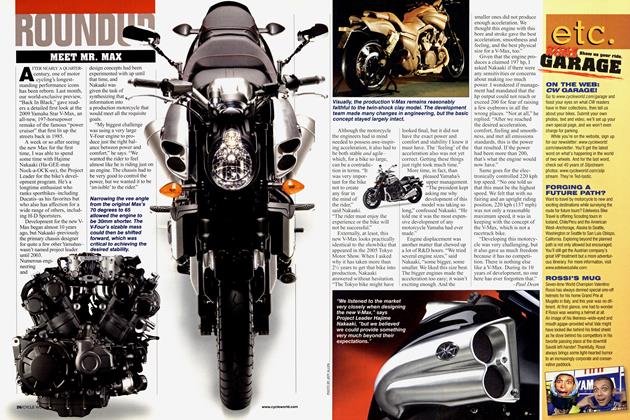

As 1956 began, MV Agusta was the pretender and Gilera the royal family, having won five 500cc titles since the war. Here is a 1956 MV 500 four-cylinder of the general type that John Surtees (now in China directing a mysterious new racing operation) rode to the first of that company’s many 500cc championships. See the swingarm pivot, passing through both the chassis and a massive lug on the back of the gearbox? The Guzzi V-Eight had this feature, as well.

The tradition persists to this day on Ducatis.

Up front is a handling revolution, the then-new telescopic fork. European teams had just passed through an enthusiasm for leading-link forks. Why not teles? People found them bendy and loose-feeling. MV’s new tele had an offset axle, allowing longer engagement between tube and slider, easing manufacture by allowing the tooling to pass completely through the slider. And, unlike link forks, it didn’t have heavy stuff behind the steering pivot causing nasty pendulum steering effects in bumpy corners.

MVs and Gileras in this time were growing brakes-bigger drums, more shoes, more cams. Why? Read race reports of the time and learn how many riders had to slow when their feeble, undersized brakes overheated. Now I’m remembering something.. .a photo of one of these 1956 bikes, showing two riders talking with Count Agusta. There is this very type of fork-leading axle, external spring. The riders are Carlo Bandirola, on the bike, looking resigned in his quilted leathers, as if something is just not right. Standing next to him is lean, tall Umberto Masetti, who achieved two 500cc titles on Gilera. All three men are gone. This machine remains.

The tales and the sounds reverberate, but these bikes weren’t very fast by our standards. In 1957, John Hartle on MV’s new six-cylinder 500 raced Dickie Dale on the flatTwin BMW at Monza, the Beemer making maybe 65-70 hp. Each bike on the front row of a 125 GP event today is making more than 60 hp.

I missed the start-up of the 1935 Husqvarna 500 V-Twin. Had the team bikes not been dropped by a dockside crane, they might have accomplished great things in the TT. This engine-originally designed by Folke Mannerstedt-is a modern reproduction, made from a photograph by a talented designer/machinist.

I stood and drank in the chassis details of Manx Nortons from 1948 onward. None of these bikes has pinch-bolts on its upper fork crown, but at the time, the Norton fork was considered state-of-the-art and was widely copied. Would I like to see the beginning of overhead cams at Norton?

Here was a CS-1 (CS for “Cam Shaft”) production version of Walter Moore’s 1927 sohc design, big as life. There was turmoil at Norton, so Moore was off to NSU two years later to design a similar engine for the Germans. So many stories start right here and lead in so many directions. I love these hearty, bulbous castings!

A 1914 Excelsior starts up. All these bikes are required to run in order to be judged. Without sound, this concours would be as absurd as a wine-viewing (no wine is poured and none tasted). The vibration is so great! As the whole machine shakes up and down, all its parts flex and chatter in unison. I think of why this is so. The bike-still clearly in the process of evolving away from the bicycle-is very light in relation to the masses of its two pistons. The reasoning is the same as why modern Fours over 1 OOOcc often have secondary balance shafts. Their piston mass is too much for the mass of the machine.

Rattle, clatter.. .1 wonder at the raw enthusiasm it took to love this action. Smoke rolled out, reminding me of early movies and stills of board-track racing. What? No oil-scraper rings? Engineers knew all about them back then-Frederick Lanchester had advocated them before 1910. Trouble was, oil scrapers tended to make the top rings wear too fast. Cars and motorcycles smoked right through the 1930s.

For more photos of The Legend Concours, go to www.cycleworld.com

A prewar BMW sidevalve came to life with a slow kick and idled languidly as if its crankcase contained millwheels. Rollers were slid under a Bultaco TSS roadracer’s rear wheel and its single cylinder ring-dinged to life. While Yamaha had its throttle-proportional metered two-stroke “Autolube” system, Bultaco simply arranged a drip from a small oil tank, its outlet at the carb bell. Straightaways were long in 1960s European racing and the simplest technology was the best. No pump is as reliable as gravity. There was one man at Bultaco who formed the exhaust pipes for these racers, using techniques familiar in old-time body shops. He was a “metal tailor.”

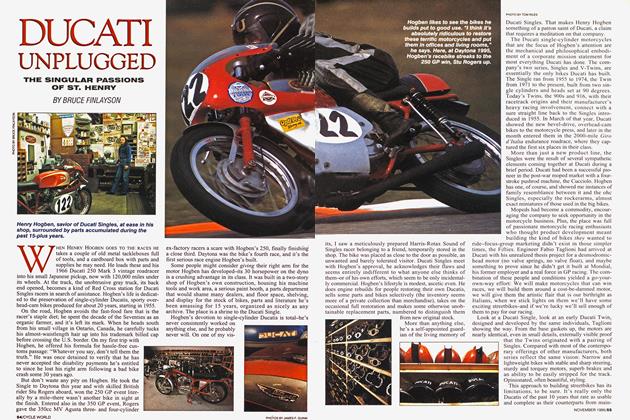

I marveled at a Matchless G45, the parallel-Twin pushrod 500 that carried the flag until Matchless decided to enlarge the 350cc 7R Single as the G50 of 1958. Few G45s were built and this is a lovely example. Earlier bikes had prominent flat surfaces but this one is positively pudgy with convexity. Matchless Twins of this period uniquely had a center main bearing (Triumph, BSA, Enfield and Norton parallelTwins-the majority opinion-had only two main bearings), but machining limitations made it the design’s Achilles’ heel. Somewhere in my files I have a copy of Jack Williams’ protocol for correctly centering this bearing. In so many cases, the success or failure of designs depended on having the right “foreman fitter.”

Nearby was a long row of MVs, mostly the production pushrod Singles with their egg-inspired crankcases, but with a peppering of racers including one very nice factory 125 dohc machine, its camboxes up on “legs” so cooling air could blow directly across the head fins. It was clear from inspection that MV liked a wide chassis with the swingarm inside it, braced solidly to the back of the engine.

And here were Giacomo Agostini and Phil Read in the flesh, titanic champions of the 1960s and ’70s. As always, Ago is smiling, always a photo op. They have ridden up from L.A. in company with Eraldo Ferracci, who was last year involved in a new Superbike effort from MV/Cagiva. Their presence makes Hailwood’s absence seem very loud, but even immortal mortals don’t live forever.

On the three-cylinder MV 500 was a pair of the forwardoffset clip-ons that Ago favored. How can those MV (Read)vs.-MV (Ago)-vs.-Yamaha battles of the early 1970s be a third of a century ago? Time passes quickly when we’re having fun.

Who are these collectors? You might expect them to be the Lintless Ones sometimes seen at upscale car shows, their faces still pink from valet shaves. Not so. I sat in the Ritzy (by definition) restaurant and watched the many coming and going. I saw quite a few of the hard faces of self-made men, often walking with a limp. Motorcycles aren’t for everyone, but they are the choice of this group. A limp? Well, you could get such a thing by having made a few twowheel experiments in your youth. If my trucking company or software shop had brought in a pile of money, I’d have that G45 or one like it. And my face would dare anyone to argue otherwise.

A collector’s helper flicked dust from yet another gem-like bike. I looked upwind to see the source of the dust. There was only the Pacific Ocean, its rollers completing their long journey from Asia and Australia.